Expressive Timing or Thematic Transformation? Onset Displacement in Performances of Jazz Standard Melodies

Sean R. Smither

| PDF | CITATION | AUTEUR |

Abstract

The rhythms of jazz standard melodies are inherently flexible prototypes that are brought to life by jazz musicians using a variety of expressive transformations. I argue that these transformations fall under two closely related categories. The first, expressive timing, involves displacements of onsets that are so small—usually in the order of milliseconds—that they do not constitute a change in metric-hierarchic position; they fall below the level of syntax. Conversely, thematic transformation often involves displacing notes to a different metric position.

In this paper, I contend that expressive timing and thematic transformation represent interrelated improvisational processes that are coordinated in performances of jazz standards. I connect these techniques to recent work on jazz ontology and referents, arguing that the ambiguous relationships between these transformational categories is the result of the ontological flexibility of jazz tune melodies. I ultimately argue that both techniques become involved in an ongoing give-and-take as the improvisational process unfolds.

Keywords: improvisation; jazz; microtiming; ontology; transformation.

Résumé

Les rythmes des mélodies de standards de jazz constituent des prototypes intrinsèquement flexibles, que les musiciens de jazz animent par une variété de transformations expressives. Je soutiens que ces transformations relèvent de deux catégories étroitement liées. La première, le timing expressif , implique des déplacements d’attaques si minimes –généralement de l’ordre de quelques millisecondes – qu’ils ne constituent pas un changement de position dans la hiérarchie métrique ; ils demeurent en deçà du niveau syntaxique. À l’inverse, la transformation thématique implique souvent le déplacement de notes vers une autre position métrique.

Dans cet article, je défends l’idée que le timing expressif et la transformation thématique représentent des processus improvisatoires interdépendants, coordonnés dans l’interprétation des standards de jazz. Je relie ces techniques à des travaux récents concernant l’ontologie et les référents en jazz, soutenant que les relations ambiguës entre ces catégories transformationnelles résultent de la flexibilité ontologique propre aux mélodies de standards. J’avance, en définitive, que ces deux techniques s’inscrivent dans une dynamique continue de compromis réciproque au fur et à mesure du déploiement de l’improvisation.

Mots clés : improvisation ; jazz ; microtiming ; ontologie ; transformation.

Introduction

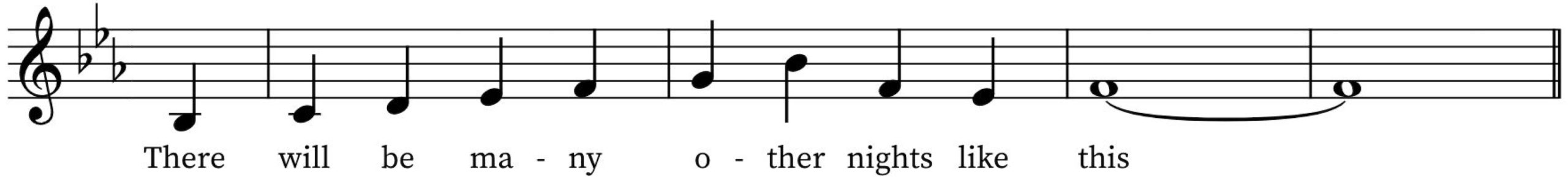

Jazz standards are inherently flexible prototypes. This fact is reflected in how melodies are rhythmically depicted in fake-book lead sheets. Consider a typical lead-sheet representation of the opening phrase of Harry Warren and Mack Gordon’s “There Will Never Be Another You,” shown in Figure 1. The melody, mostly stepwise and oriented around the downbeats of hypermetrically strong measures,1For more on the organization of hypermeter and hypermetric emphasis, see Lerdahl and Jackendoff (1983, 69–100), Waters (1996), Temperley (2008), and Salley and Shanahan (2016). is represented almost entirely using rigid quarter notes. For those unfamiliar with this composition, the rhythms of the melody as written might appear dull and unimaginative.

Figure 1: “There Will Never Be Another You,” opening phrase.

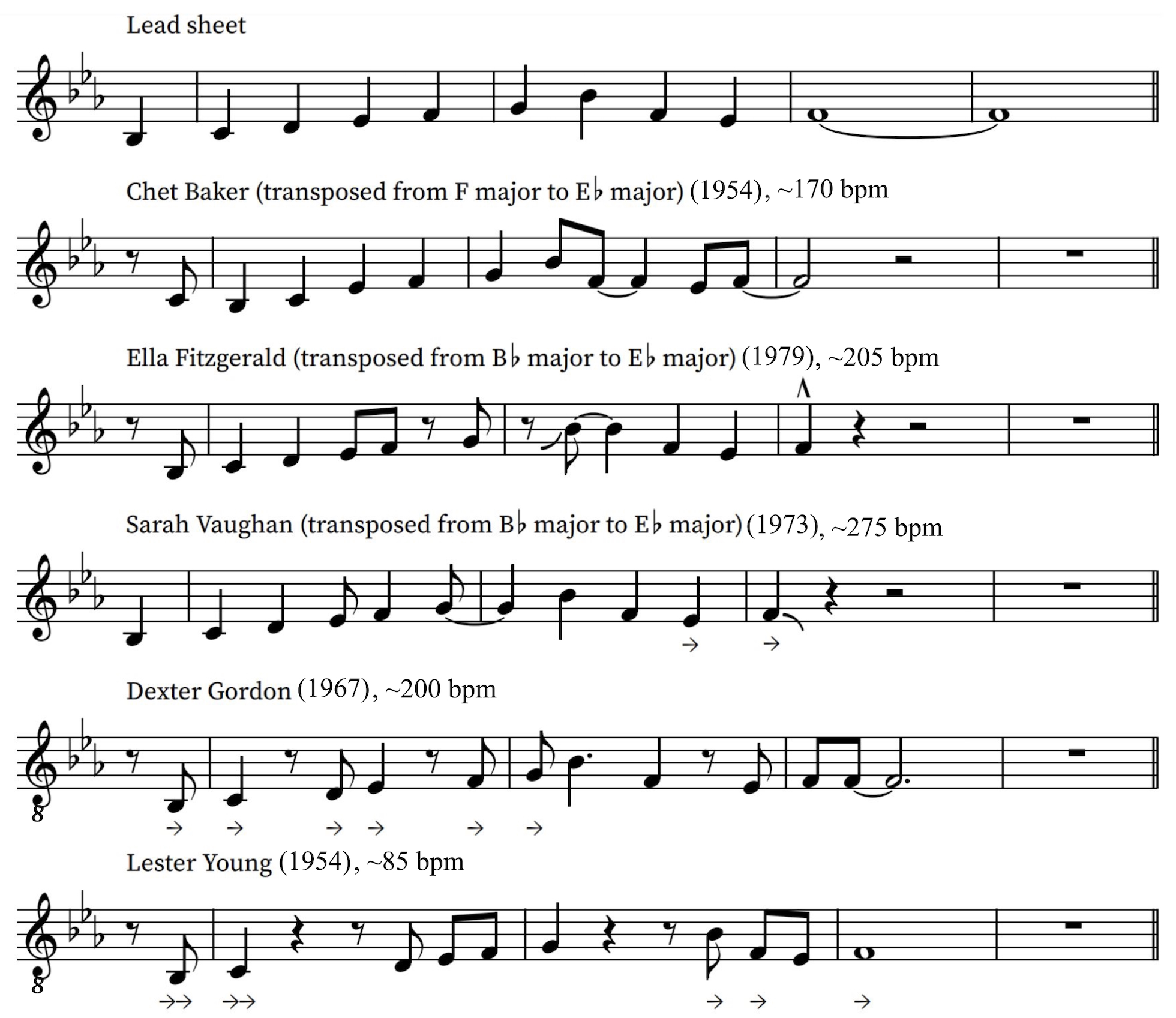

Actual renderings of the melody, however, are lively, inventive, and notably individual from one rendition to the next. Figure 2 demonstrates how different jazz musicians bring this phrase to life through both expressive timing (indicated in the example by arrows) and larger thematic transformations, resulting in utterances that differ significantly from the lead-sheet representation.2Expressive timing refers to small changes in the onset positions and/or durations of notes; for an overview of expressive timing and its history, see Ohriner (2019). Both expressive timing and thematic transformation are defined and discussed in more detail below. While “There Will Never Be Another You” is an especially notable example of such simplified rhythmic representation, it is not unique among jazz standards: many, if not most, standards from the “Great American Songbook” era are typically notated using deliberately simplified rhythms.3The so-called “Great American Songbook” era includes works by composers such as Richard Rodgers, Jerome Kern, George Gershwin, and Harold Arlen. Later melodies from the bebop era onward are notably more specific in their rhythms, though this is not to say that later melodies are not also transformed considerably.

In this article, I argue that expressive timing and thematic transformation represent interrelated improvisational processes that are coordinated in performances of jazz standard melodies. The coordination of these processes not only serves to make performances more compelling than abstract representations of tunes would suggest but also reflects and contributes to both the unique ontological status of jazz and the aesthetic principles that guide jazz practice writ large. I begin by differentiating between expressive timing and thematic transformation before exploring the various ways that they interact. I then relate the interplay between timing and transformation to the ontological status of jazz standards, as well as to the African-American aesthetics of jazz. Two case studies help illuminate this interplay. First, a comparative analysis of a small corpus of performances of “There Will Never Be Another You” shows how different improvisers navigate the expressive affordances of a rhythmic template, resulting in a variety of different interpretations of the same melody. Second, an analysis of Cécile McLorin Salvant’s recording of Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart’s “I Didn’t Know What Time It Was” examines the dynamic, projectional processes that shape timing and transformation as a performance unfolds. I conclude by outlining some possible future lines of inquiry centred around the relationship between jazz ontology and rhythm.

Figure 2: Transcriptions of the opening phrase of the first A section in the opening head of “There Will Never Be Another You” from a selection of recordings.4In each transcription, determinations of microtiming were made by comparing the onsets of the lead instrumentalist or singer to those of the rhythm section, particularly the bass and drums. For more on the perception of beats in jazz, particularly with regard to discrepancies within the rhythm section, see Butterfield (2010).

Throughout the article, my focus is primarily on how listeners might interpret an improvisation as it unfolds rather than on the perspective of the improviser. There are two main reasons for this focus. First, the improvisational process is notoriously difficult to excavate, both because it involves complex creative processes and because it occurs in time, in contexts that are always rapidly evolving.5For more on the improvisational process and the factors that render it opaque to not only researchers but improvisers themselves, see Pressing (1984, 1988) and Norgaard (2011). For more on the ways that improvisational contexts relate to time, see Stover (2017). While the intentions of improvisers are ultimately unknowable to audiences, listeners nonetheless make assumptions about these intentions as they interpret improvised musical utterances. Examining the perspective of the listener allows us to consider what factors are involved in such ascriptions of intention. The second reason is that improvisers are themselves listeners, not just in the trivial sense that they are also hearing the performance but rather in the sense that they actively use the information gleaned from listening to inform an ongoing improvisation. This results in a feedback loop wherein listening, and all the interpretive decisions that it involves, continuously plays a role in the generation of improvised behaviour.6This feedback loop is theorized in Hodson (2007) and Michaelsen (2013). In this sense, examining the ways in which listeners interpret improvisations can also provide insight into the improvisational process itself.

Rhythmic versus Metric Expressive Timing

The distinction at the heart of this article is between expressive timing and thematic transformation.7Anne Danielsen (2015, p. 54) argues that the notion of “expression” in most descriptions of microtiming is a relic of an outdated divide between structure and expression. While the term certainly reflects this mapping, I continue to use the term in this study because I find that such timing in jazz is frequently read by listeners as expressive, especially when it is marked and understood as explicitly transformational, not just part of the “participatory discrepancies” (Keil 1987) that animate an ongoing groove. It is therefore an evocative term that can refer to a particular microtiming strategy, rather than as a catchall for timing discrepancies more generally. The meanings and connotations of these terms can be somewhat ambiguous and are contingent on the style and ontological statuses of the musics involved. Broadly speaking, there exist at least two distinct conceptualizations for expressive timing: the first involves the shortening or lengthening of durations, while the second involves anticipated or delayed onset positions. Because these two conceptualizations are related (a short duration means the next onset is earlier), they are often conflated. The tension between these competing definitions is captured in Mitchell Ohriner’s chapter on the topic in The Oxford Handbook of Critical Concepts in Music Theory. Ohriner first defines expressive timing as “variation in performed durations among notes represented in a musical score with a single rhythmic value” (Ohriner 2020, p. 369), but later concedes that “generally, expressive timing addresses the time intervals between note onsets in performance” (Ohriner 2020, p. 374, emphasis added). While both conceptualizations offer valid ways of engaging with timing, it will be useful to clarify the relationship between the two perspectives. Confusion between these conceptualizations likely arises as an artifact of an underlying conflation of durations and metric onset position. Durations may either be measured from a note’s onset to its release––what Daphne Leong (2000, p. 65) refers to as “value duration” (vdur)––or from one onset to the next onset, the interonset interval (IOI) between two chronologically adjacent notes.8Leong (2000, p. 65) refers to IOIs in this sense as “interval duration” (idur). Depending on how expressive timing is conceived within a given style, changing the length of value durations or IOIs may or may not change the underlying metric position of a note. If the entire metric grid is affected by expressive timing, an onset’s metric position is not altered even though durations change; because the timing applies to the entire metric grid, I call this metric expressive timing.9Metric expressive timing and rubato are sometimes coterminous, although some implementations of metric expressive timing may not be severe enough to be considered rubato. Hudson (1994, p. 1) describes two types of rubato; his “early” rubato encompasses what I call rhythmic expressive timing, while the “later” type mostly resembles metric expressive timing. For more discussion on the relationship between these conceptions as they apply to jazz, see Ashley (2002) and Benadon (2009b). If the underlying metric grid remains static and an onset arrives earlier or later than expected, the duration of the part(s) enacting the metric grid do not change while the durations of the part featuring the expressively-timed rhythm fluctuate; because the timing applies only to the rhythm and not the underlying metric grid, I call this rhythmic expressive timing. Generally speaking, rhythmic expressive timing is common in groove-based musics, while metric expressive timing is more common in the Western concert tradition. In this article, I am chiefly concerned with rhythmic expressive timing.

Ohriner notes that much of the literature on expressive timing centres on the analysis of recordings of performances of the same notated work, usually from the Western canon. Because of the “works for performance” ontological paradigm at play in these studies, the score is understood to be ontologically prior and notes in the score specify particular onset positions that are not movable within the metric structure.10The term “works for performance” is introduced by Stephen Davies (2001) to describe an ontology of musical works in which a score (or equivalent artifact) is used to generate a performance; Davies argues that this ontology is operative for most of the history of Western concert music. Put simply, performers cannot (or, more accurately, choose not to) change the metric location of note onsets because those onset positions are indicated by the score, so discrepancies between performances are attributable only to shortened or lengthened durations of notes, resulting in metric expressive timing.11As Nicholas Cook (1999) argues, performance choices in Western concert music have often been misconstrued by theorists as emanating from the work rather than the performer, reinforcing the idea that performers have little true agency and simply serve as vessels to communicate the musical work. Still, there can be little doubt that departing in salient ways from a notated score remains rare in Western concert music, even in repertoires where improvisation would historically have been expected; for notable critiques along these lines, see Levin (1992) and Taruskin (1995, especially Chapter 17, pp. 334–346). This malleability of durations necessarily means that the IOIs between tactus onsets—the beats that comprise the main metric pulse to which listeners primarily entrain—are likely to be flexible and inconsistent while the underlying metric positions of notes are identical between performances.12For more on the constraints and affordances of metric entrainment, see London (2004).

In most groove-based musics (including most mainstream jazz), expressive timing is primarily rhythmic. The IOIs at the tactus level of the groove remain relatively consistent in order to ensure that listeners and dancers are entrained to the groove and are “constantly sensorimotorically engaged” (Câmara and Danielsen 2019, p. 273). Discrepancies between renderings of the same rhythm do not hinge on the durations of the metric grid being altered but rather on the onsets themselves arriving early or late in comparison to the static groove. When such discrepancies occur at a micro-level within the groove itself, they fall within what Anne Danielsen (2018) terms a “beat bin” and create what Charles Keil (1987) memorably referred to as “participatory discrepancies” (PDs).13Keil’s theorization inspired a number of subsequent studies on participatory discrepancies in jazz, including Prögler (1995), Waterman (1995), Givan (2007), and Butterfield (2010, 2011). Keil’s notion of PDs highlights the embodied aspects of performance, but is often oriented not around expressive timing against a metric framework but rather subtle asynchronies between parts, such as individual instrumentalists playing a bit ahead of or behind the beat relative to one another; Danielsen’s later work on beat bins provides a more formalized theoretical framework for making sense of these kinds of PDs. Both of these concepts describe rhythmic events that fall below the threshold of the metric hierarchy. To borrow Fernando Benadon’s metaphor, there is no metric “safety net” for them to fall on, no level of the metric hierarchy that satisfactorily captures their relationship to the metric framework.14Critiquing conventional music-theoretical approaches to microtiming, Benadon characterizes the safety-net approach as follows: “If you sing a note and find you cannot pin it to one layer, try the one below. You may have to go as low as thirty-second notes or even resort to borrowing ternary division, but eventually your note will land on a safety net” (2024, p. 4). Such events are often described as “microrhythm” or “microtiming.”15The term “microtiming” is introduced in Iyer (1998) and is discussed in detail in Iyer (2002).

When notated, microtiming usually does not warrant a change in rhythm and so may be identified in notation using a left- or right-facing arrow above or below the note to indicate relative earliness or lateness. When discrepancies between renderings of the same rhythm occur at a macro-level through thematic transformation, the rhythms will usually be notated differently to more accurately reflect the onset’s relationship to the meter. Importantly, most groove-based musics, including the majority of jazz, do not rely on a score in a strict work-determinative relationship. Comparative analysis is still possible in such musics—and indeed, the present article undertakes just such an analysis—but the point of comparison is the displacement of onsets from expected arrival points in relation to an underlying groove. This is not to dismiss the fact that, in performances of scored works that adhere to the notation, onsets still occur in a metric framework and in a context of always-evolving expectations. Rather, the point here is to emphasize that the way expressive timing is conceptualized and measured is often fundamentally different in groove-based musics that lack a definitive score, and therefore much of the literature that deals with expressive timing through durational changes necessarily involves a different methodology than the one employed in the present article.16In groove-based musics, durations still change in the layer of the music that involves expressive timing, but these durations are limited to the part that features expressive timing and are constrained in part by the needs of the groove. If the total duration of the excerpt is to be synchronized with the underlying groove, a stretched duration will need to be complemented by a contracted duration (often a rest) somewhere else, enacting what Hao and Rachel Huang (1994–5) call “dual-track time.”

A hard conceptual delineation between metric versus rhythmic expressive timing can be somewhat misleading, as small changes to timing in the groove can affect the perception of onset position on a micro-scale. Likewise, both kinds of expressive timing ultimately rely on a combination of the expectations engendered by metric frameworks (a “virtual” reference structure) and the unfolding durations of notes heard against those frameworks (the “actual” rhythms).17For more on the comparison of virtual reference structures to actualized rhythms, see Danielsen (2015, 2018). Danielsen’s virtual/actual distinction is informed by Gilles Deleuze’s use of the terms; for more on the interplay of the virtual and actual in jazz and improvisation more generally, see Stover (2017). Nonetheless, the regularity of the tactus IOIs is an important part of how expressive timing works in most groove-based musics, as the meter does not bend with the durational changes. This conceptual distinction arguably reflects how performers conceptualize expressive timing in different styles as well, with expressive timing in groove-based music oriented primarily around the notion of anticipations and delays of onsets rather than the shortening and lengthening of durations, which are more typical of thematic transformation.18In such a conception, the shortening or lengthening of durations is understood as either a natural consequence of a change of onset position or as a separate interpretive choice altogether.

For the purposes of this article, expressive timing refers to onsets that are displaced from an inferred, idealized metric position to a sufficiently small extent that their metric position is not perceived as intentionally altered.19It is important to note that this does not mean that the expressive timing is not intentional. Rather, if a note is perceived as anticipated or delayed via expressive timing, this means that the listener does not hear the note’s metric position as intentionally altered, even if the timing change could potentially be heard as a change in metric position. This definition of rhythmic expressive timing presupposes the existence of an ongoing metric hierarchy to which listeners (including performers) are entrained and against which the displacement is registered. Rather than warping the entire metric grid itself with variable IOIs, displacements are heard against a relatively consistent, idealized tactus; salient variability of IOIs occurs only within one part (for the purposes of the present study, whoever is playing or singing the melody), and is compensated by altered durations elsewhere in a given timespan, often through expansion or contraction of rest durations, in order to remain relatively synchronized with the prevailing metric grid.

Intention plays an important role in the definition of expressive timing provided above. By “perceived as intentionally altered,” I do not refer to the actual intentions of the improvisers themselves (which are ultimately unknowable to listeners in most cases) but rather to listeners’ inference of such intentions, to the extent that such inferences are influenced by information available in the sonic trace of an improvisation and cross-referenced against expectations engendered by knowledge of the style. This distinction is worth making because the location of a note’s perceptual centre (P-centre) can in many cases be ambiguous.20The notion of a perceptual centre first appears in Morton et al. (1976). P-centres are also closely connected to the notion of beat bins (Danielsen 2018). As Danielsen et al. (2019) argue, determinations of a note’s P-centre are influenced by a note’s timbre, harmonic context, rhythmic/metric context, style, amplitude envelope, and more. In ambiguous cases, the temporal location of the P-centre may be determined by a listener not only through the raw data of timing but also through the listener’s situated perception and judgment of whether a note’s temporal position has been intentionally displaced. For example, if a note in a well-known melody typically falls on a downbeat, and its onset in a performance begins on the downbeat but features a P-centre just after the downbeat, a listener may nonetheless hear the note as a “late” downbeat because they are expecting the note to fall on a downbeat and assume that the note is not being intentionally displaced. Although discernment of intention is inevitably subjective and therefore a thorny issue, it is inarguably an important part of how informed listeners understand an unfolding improvisation.

Determination of onset placement intention and P-centre is closely related to the problem of identifying “errors” in improvisation. Stefan Caris Love (2016, p. 64) defines an error as “a moment or passage that would likely register as incorrect within the community of jazz musicians and listeners.” He distinguishes between two kinds of errors, “competence errors” and “performance errors.” According to Love, “‘competence errors’ stem from a speaker’s deficient knowledge of the language—for example, a child’s use of ‘goed’ for ‘went’—while ‘performance errors’ stem from the contingencies of actual speech—for example, a native speaker’s accidentally saying ‘black bloxes’ for ‘black boxes,’ due to fatigue, speaking too quickly, and so on” (2016, p. 64). While expert jazz improvisers seldom make competence errors, performance errors are an inevitable part of improvisation. An early or delayed note may in some cases be understood as an error—which is to say, the note is not heard as being intentionally displaced. It is important to note that errors are not necessarily negatively valenced. Thanks to the relatively capacious beat bins typical of jazz grooves and the permissiveness of improvisation-oriented aesthetics, errors made by jazz musicians are seldom considered to be problematic, and indeed may even be welcomed as a signal of authenticity.21For more on the relationship between errors, spontaneity, and authenticity in jazz, see Walser (1993). Finally, it must be emphasized that expressive timing is typically not an error, but rather is most often intentional and correctly interpreted as such. Intentional expressive timing, however, is different from intentional metric displacement; distinguishing between these two categories requires a listener to infer an underlying template that is being transformed and to hear the transformation against this template.

How Does This Tune Go? Standard Melodies and Thematic Transformation

Thematic transformation is a significantly larger category than expressive timing and can be used to refer to a wide range of transformations of existing thematic material. Most broadly, thematic transformation refers to transformations of pitch, rhythm, articulation, and so on, such that the thematic material remains recognizable in the transformation. For the purposes of this article, I am interested specifically in rhythmic transformations of the melodic material of jazz standards that mostly preserve pitch content; in short, onset displacements. In terms of onset displacement, thematic transformation involves onsets that are displaced from an inferred, idealized metric position to a sufficiently large extent that their metric position is perceived as intentionally altered. Thematic material must be identifiable as such by a listener; in order to hear a transformation as a transformation, we must have some kind of template or prototype against which we can compare the transformation (even if that template is fuzzy or emergent).22Zbikowski (2002, 201–242) discusses how jazz tunes may be conceptualized as prototypes by adapting aspects of Eleanor Rosch’s theory of categories and prototypes to models of music ontology.

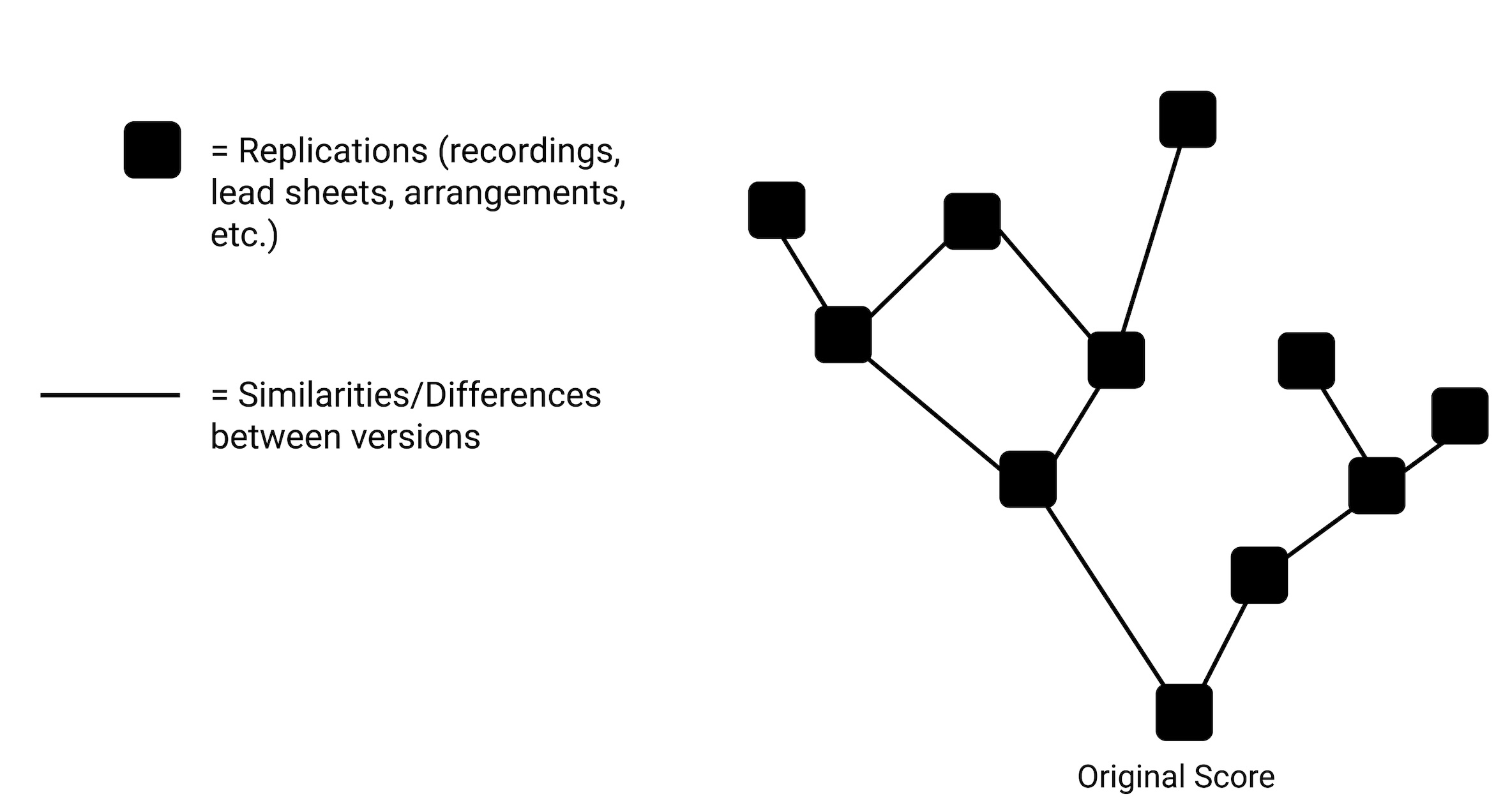

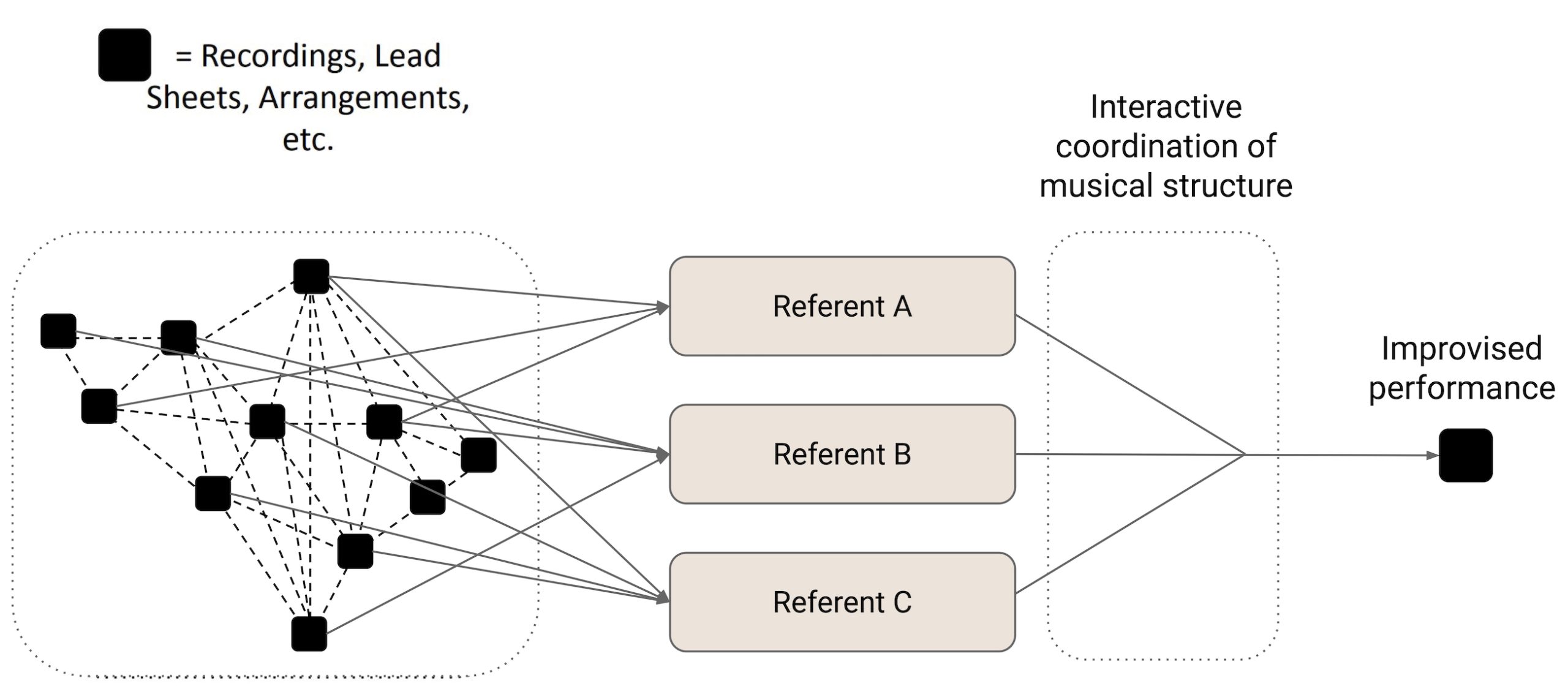

When it comes to jazz standards, identifying the precise nature of thematic material—the virtual reference structure that forms the set of expectations against which listeners can compare utterances—can be quite problematic because no definitive version of any given jazz tune exists. Instead, as Brian Kane (2024) argues, extensive transformational replications, propelled by various kinds of technological mediations, give rise to a network of performances related only by family resemblances but nonetheless governed by a kind of work-performance ontological paradigm.23Kane (2024) adopts the concept of replication from Davis (1996). Kane’s network-based account of jazz ontology is based on Georgina Born’s (2005) work on the impact of mediation on ontology, and José A. Bowen’s (1993) adaptation of Wittgenstein’s theory of family resemblances. This likewise resonates with Gilles Deleuze’s differential ontology, particularly his account of the relationship between the virtual and the actual; for an application of these terms to music ontology, see Assis (2018). This process is depicted in Figures 3a, 3b, and 3c. First, the original score (or some equivalent original document, recording, etc.) gives rise to many replications, while other later replications are based on earlier replications rather than the original score (Figure 3a).

Figure 3a: A network of versions (scores and recordings) of a jazz tune.

When looking at the resulting network, we are faced not with a linear, chronological set of relations but rather a set of family resemblances: all versions share something with other versions, but few features are shared across the entire network, meaning that features can only be sufficient but not necessary in determining ontological status (Figure 3b).

Figure 3b: The same network from Fig. 3a, with lines of influence replaced by abstract family resemblances.

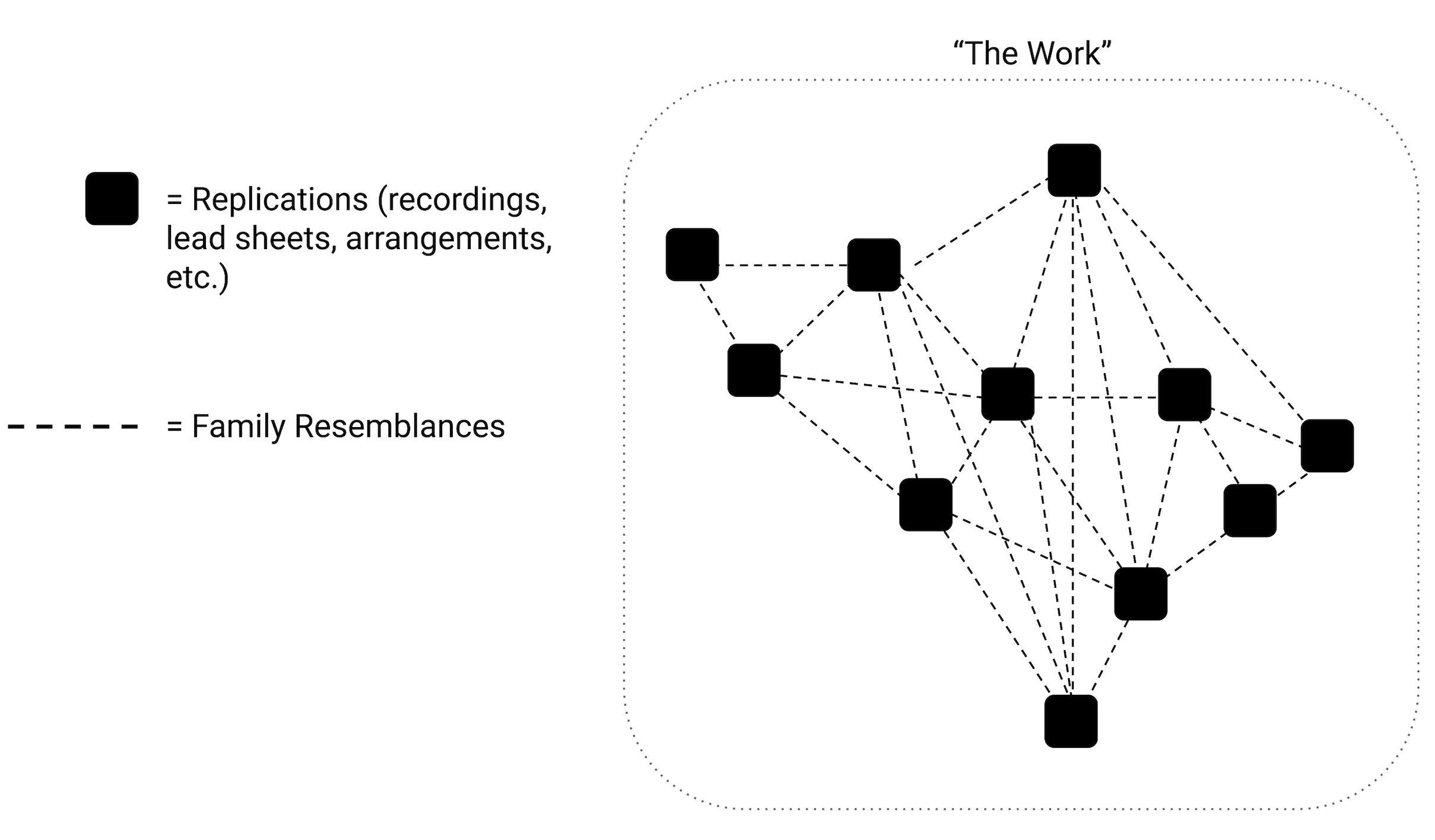

This network of family resemblances, stripped of most of the linear generating relationships between versions, becomes what I have previously termed an avant-texte (Smither 2021), a network of versions that improvisers draw from to fashion referents for improvisation, which are then negotiated against one another as part of the improvisational process to create a coordinated performance (Figure 3c). If we are to compare any given performance to “the tune” on which it is based, we will need to specify a grounding foil for the comparison. Because jazz improvisers become familiar with a tune through networks of performances, those same networks can be used to facilitate comparative analysis.24Smither (2024) presents a methodology for undertaking this kind of comparative analysis.

Figure 3c: Smither’s (2021) schematic of jazz-tune networks and their role in the improvisational process.

Thanks to the ambiguous nature of jazz standards, transformation is an aesthetic imperative. On the one hand, jazz improvisers cannot reliably know exactly which versions of a tune audiences will be familiar with. The fuzzy identity of the tune fans out from a more defined core of essential features, meaning that small transformations that fall within the fuzzy space between tune identity and improvisation may or may not register as transformations. On the other hand, this ambiguity means that a wide range of improvised interpretations are typically afforded by any given tune, and small discrepancies will not only be tolerated by audiences but will be in most cases preferred to a static, quantified alternative. This aesthetic framework is grounded by a number of stylistic features and tropes typical of African-American musical cultures, especially that of what Henry Louis Gates Jr. (1988) terms “Signifyin(g),” a marked kind of “repetition with a signal difference” whereby improvisers playfully transform existing musical material and, in doing so, open up a rich interpretive-dialogical space. This practice forms a part of what Samuel Floyd (1991, pp. 276–277) characterizes as “Call/Response,” a conversational mode of expression common in most musics of the African Diaspora.

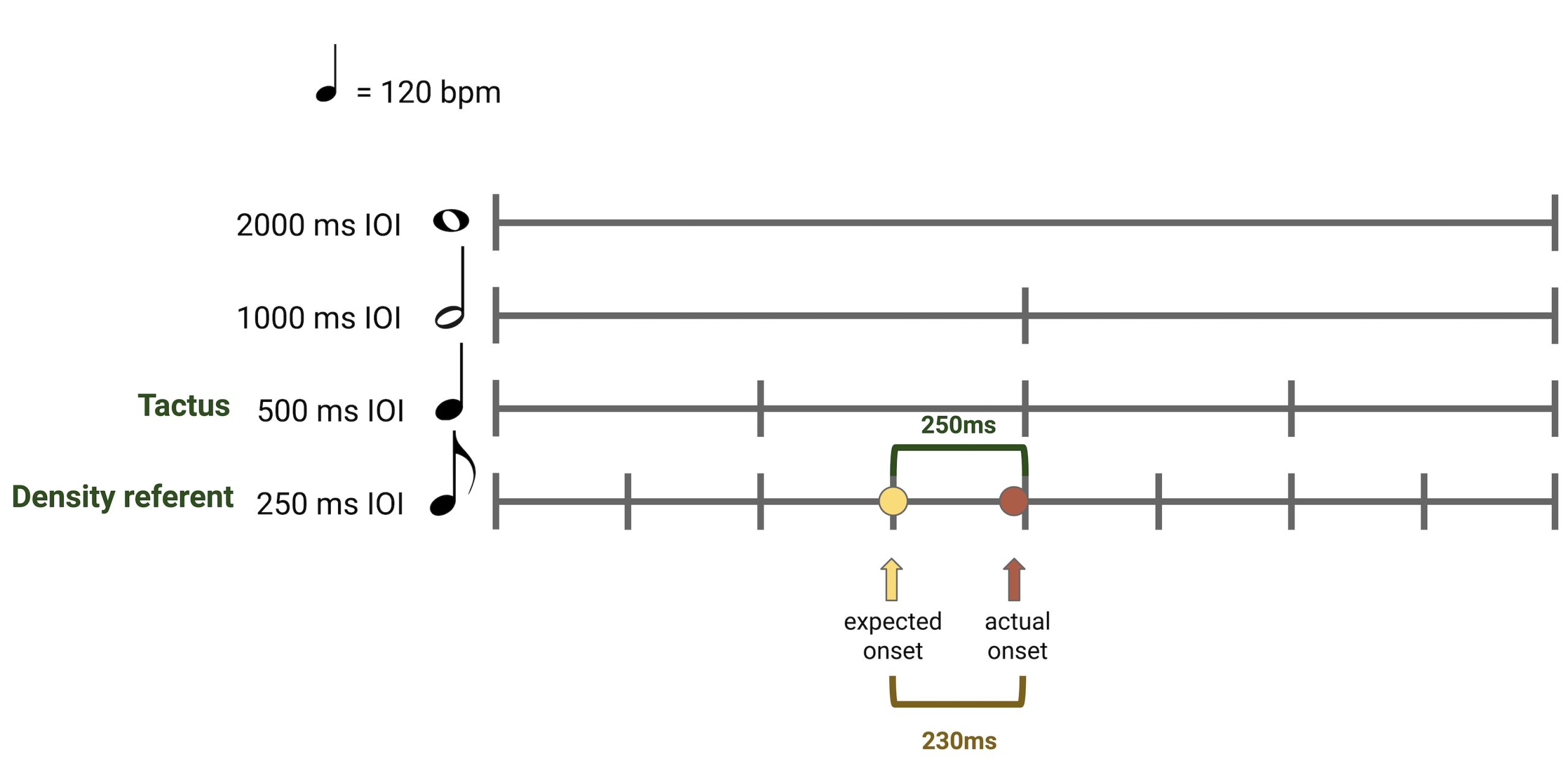

Expressive Timing vs. Thematic Transformation

If we are to differentiate between expressive timing and thematic transformation, it will be important to draw a clear line between them: How far from the prototypical template must a note be in order to be heard as a part of a thematic transformation and not simply expressive timing, or what is the threshold at which point a shift in onset placement moves from expressive timing to thematic transformation? As we will see, these questions oversimplify a complex set of considerations.25For a closer look at how context can affect ascriptions of displacement and syncopation see Leong (2011). For more on displacement in jazz styles, see Waters (1996). Nonetheless, attempting to answer them will provide a useful starting point for this discussion. We might begin by assuming that judgements of this threshold are determined in part by the metric hierarchy in which a rhythm is embedded. In particular, the tactus—which serves as the main pulse of the hierarchy to which listeners entrain (London 2004, p. 18)—and the density referent, the lowest subdivision of a metric hierarchy that is regularly present, will both help to guide judgements of how a note fits (or does not fit) into the metric hierarchy.26The density referent was first introduced by James Koetting (1970) and developed by J.H. Kwabena Nketia (1974) and refers to the lowest subdivision of a metric hierarchy heard regularly. Koetting’s relatively strict early definition is critiqued in Agawu (2006). For more on the role of density referents in groove-based musics, see Câmara and Danielsen (2019, p. 277). Figure 4 shows a portion of a metric hierarchy in 4/4 at 120 bpm, in which typical eighth-note IOIs will be about 250 ms apart. If an eighth-note onset arrives 230 ms late, we might expect that this should be close enough to where listeners expect to hear the next eighth-note onset that the displacement may be heard as belonging to the next beat, no longer a mere expressive delay but rather a displacement to a different part of the metric grid.27Justin London (2004, p. 29) posits that, based on the results of a variety of studies on both perceptual and performance limits, an IOI of ≈100 ms is the shortest possible IOI in a metric cycle. However, recent work on West African dance drumming by Rainer Polak (2017) suggests a lower threshold of ≈80 ms. Note that many contextual factors will affect the perception of what beat the onset belongs to. As Benadon (2009a, p. 17) writes: “In order for a note onset to be perceived as deadpan, it need not occur exactly on the beat or one of its subdivisions. Given a small enough discrepancy, the nominally displaced attack will be absorbed—that is, quantized—by the nearest subdivision, and the result will be perceived as a metronomic onset.”28As Benadon (2009a, pp. 17–20) notes, tempo plays a particularly important role in such determinations. When an onset is sufficiently distant from a subdivision to be perceived as “non-metronomic,” it falls into what he calls a “rubato zone” (17), which helps to afford flexible timing. Rubato zones make up a larger percentage of a given timespan at slower tempos, while conversely the opportunity for flexible timing diminishes as the tempo increases. If the note registers as expressive timing, the location in the metric grid has not changed. If the note registers instead as a displacement, the location of the note has shifted and the listener no longer hears the note as significantly delayed but rather as slightly early. This ambiguity is heightened in cases involving swing ratios, also called beat-upbeat ratios (BURs).29The term “beat-upbeat ratio” is introduced in Benadon (2006) and is expanded on significantly in Benadon (2024). When eighth notes are swung, the second eighth note in a pair of swung eighth notes (the upbeat) will typically be much shorter than the first, with its onset considerably closer to the next quarter-note onset. An upbeat onset that arrives late in a swing context is therefore likely to arrive very close to the next quarter note, engendering metric ambiguity.

Figure 4: A segment of a 4/4 metric hierarchy at 120 bpm with a potentially–ambiguously displaced onset.

In actual performance contexts, things are much more complicated. A variety of factors will influence perceptions of where such a threshold might fall, including the tempo of the performance; whether the density referent is swung and, if so, the size of the BUR; the melodic and harmonic context of the note in question; the timbre and perceptual centre of the note; the timings and timbre of the other parts that help to provide the metric context; the participatory discrepancies between those parts; and more.30This emphasis on contextual interdependence resonates in some ways with aspects of Chris Stover’s (2017) Deleuzian interpretation of time in improvisation. This means that every note in a performance will have a slightly distinct threshold based on its context. This threshold is subjective and therefore may differ between listeners based on the factors that condition their own expectations.

The nebulous nature of these thresholds can be utilized by improvisers in playful, dialogical ways within the Call/Response aesthetics of jazz. Rather than trying to pinpoint a threshold that is context-dependent and always changing, we will instead examine how the ambiguous nature of these thresholds provide affordances from which we can glean insight about improvisational processes.31For more on the relationship between jazz improvisation and affordances, see Love (2017).

Case Study 1: Comparing Performances of “There Will Never Be Another You”

A comparative analysis will help to illuminate how expressive timing and thematic transformation inflect unfolding improvisational processes in different ways. Let us return here to the opening bars of Warren and Gordon’s “There Will Never Be Another You.” I have selected this tune because it is an especially blank rhythmic canvas for jazz musicians: the rhythms are typically notated as lengthy strings of quarter notes, broken only by a few dotted figures and held notes at the ends of phrases. I focus on the opening bars of each rendition, corresponding to the lyrics “There will be many other nights like this.” The treatment of this brief melodic phrase is especially revealing because the rhythms introduced here at the beginning of the tune often influence the other melodic statements throughout the head, each of which mimics this opening phrase.

Jazz musicians rhythmically realize this melody in a variety of ways. A sample of these approaches was shown in Figure 2. I have selected these renditions because they feature influential figures from throughout jazz history: trumpeter/singer Chet Baker (playing the trumpet in this excerpt); singers Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughan; and tenor saxophonists Lester Young and Dexter Gordon. Despite its small size, this corpus of recordings also spans a range of tempos, from Lester Young’s languid ballad tempo (~85 bpm) to Vaughan’s brisk uptempo take (~275 bpm). While this selection of recordings is far too small to make generalizations about the tune or performances of it, it is nonetheless enough to give us a sense of the variety of rhythmic interpretations afforded by the tune and how some of those interpretations might interface with one another.32The comparative study that I present in this article is in this sense distinct from the kind of inquiry typical of corpus studies. For more on corpus-based music-theoretical research, see White (2023).

Media 1: Chet Baker’s opening phrase of “There Will Never Be Another You.” Listen to Media 1.

Media 2: Ella Fitzgerald’s opening phrase of “There Will Never Be Another You.” Listen to Media 2.

Media 3: Sarah Vaughn’s opening phrase of “There Will Never Be Another You.” Listen to Media 3.

Media 4: Dexter Gordon’s opening phrase of “There Will Never Be Another You.” Listen to Media 4.

Media 5: Lester Young’s opening phrase of “There Will Never Be Another You.” Listen to Media 5.

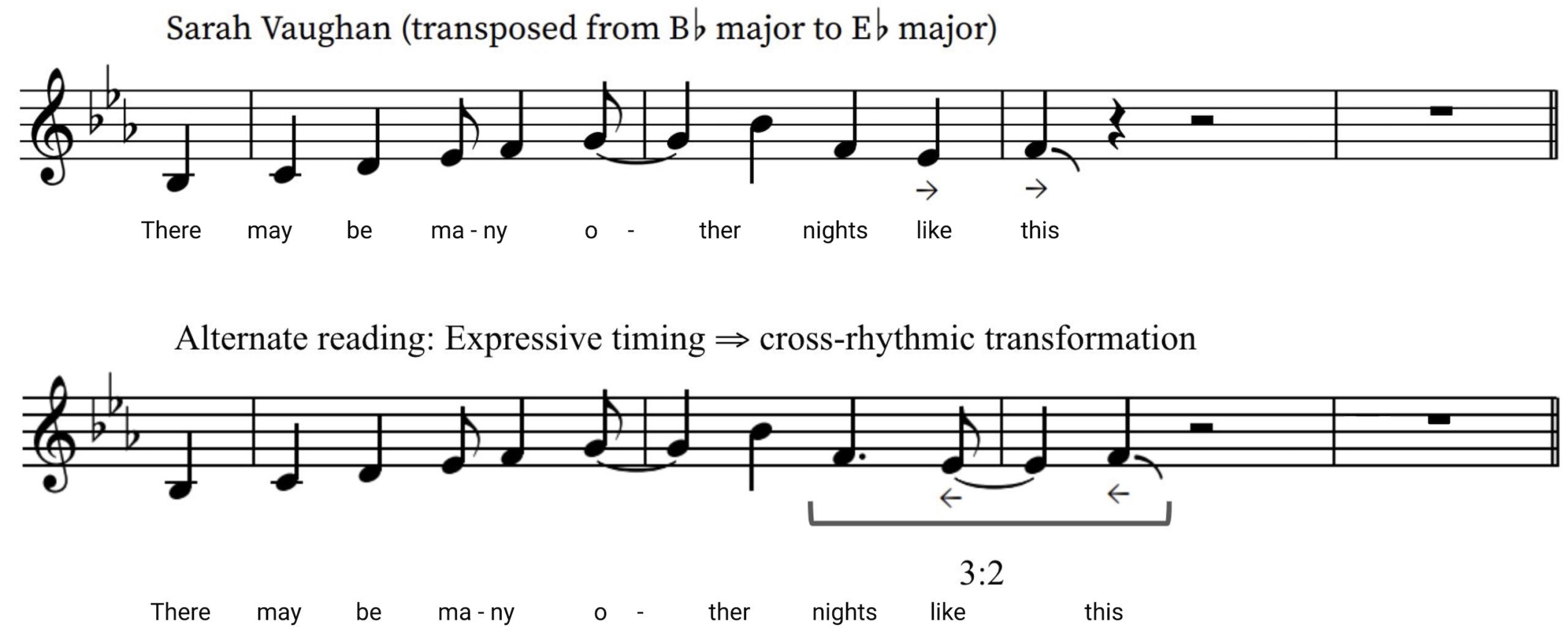

A few observations will help us compare these recordings against one another. Chet Baker’s performance retains the even quarter notes of the lead-sheet representation in the first measure before introducing some motivic syncopation in the second half of the phrase, echoed a measure later by pianist Russ Freeman (Media 1). Ella Fitzgerald syncopates the middle of the line, departing from on-the-beat quarter notes at the beginning and returning to them at the end of the phrase (Media 2). Sarah Vaughan’s recording features similar syncopation in the middle of the line but also features some notable delays at the end of the phrase (Media 3).33Vaughn’s melody can alternately be heard as a metered cross-rhythm, an interpretation to which I return below. Dexter Gordon transforms the rhythms of the opening of the phrase with a short anacrustic motive, grouping each pair of notes in the opening measure together (Media 4). Finally, Lester Young dramatically delays his initial onsets, then leaves large rests between excerpts of the phrase (Media 5).34Both Lester Young and Dexter Gordon delay the opening note of the melody such that it may be interpreted as starting on the downbeat rather than the “and” of four. I return to this possibility below. While the simplified lead-sheet notation appears at the top of Figure 2 for comparison, we should remember that jazz musicians are not typically generating their performance by looking at any lead sheet, let alone this particular lead sheet. Rather, performers will be referring to the network of versions with which they are familiar, that is, to their own referent of the piece. Our referent as listeners will likewise depend on our familiarity with different renditions.35For more on the ways that familiarity with different recordings may impact referents, see Givan (2012), Kane (2024), and Smither (2024). For the purposes of this article, familiarity with the versions in Figure 2 provides an informal, flexible template against which we can compare each individual expression.

A few trends are worth noting. First, each performance preserves the opening anacrusis—mostly with an eighth note, sometimes with a quarter note—and the downbeat of the first measure. Second, with the exception of Lester Young’s rendition, no single note’s onset arrives more than a nominal eighth note away in either direction from the strict quarter-note onsets suggested in the lead sheet. (In this sense, the lead sheet does a surprisingly good job of presenting an “averaged-out” representation of the melody, capturing a range of standard rhythmic possibilities, if not the actual probabilities of onset locations.)36Lead sheets often aim for this kind of neutral representation of rhythms; in this way, the rigid quarter notes of “There Will Never Be Another You” may be understood not only as a simple way to represent the melody but also as a neutral representation of a wide range of rhythmic possibilities, as evidenced even by the small corpus of Figure 2. As Folio and Weisberg (2006) note, a single artist interpreting the same tune multiple times may create strikingly divergent renditions, even when the transformational strategies the artist employs are similar between renditions. Finally, salient syncopations are usually balanced out by on-the-beat anchors.37For more on the relationship between anchors and rhythmic transformations, see Benadon (2009a) For example, Baker’s line begins with quarter notes, leaving all syncopation for the end of the line, whereas Fitzgerald’s syncopation occurs only in the middle of the line.

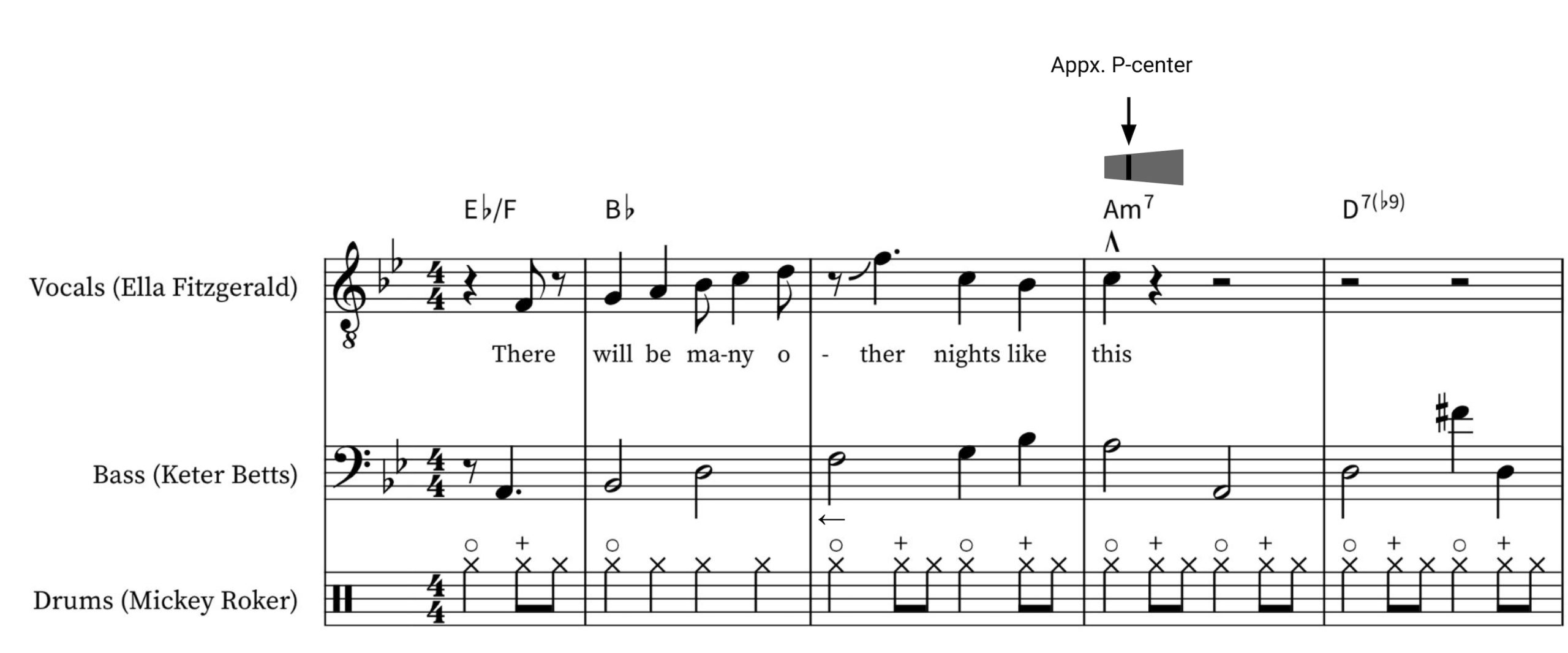

A few renditions feature especially revealing interplay between expressive timing and thematic transformation. Consider the two vocal renditions, one featuring Ella Fitzgerald and the other featuring Sarah Vaughan. Both vocal excerpts use similar rhythms in their first halves until they diverge in their second halves. Fitzgerald’s final note—corresponding with the word “this”—features a slight delay to the perceptual centre (P-centre) of that note, alongside a slight crescendo as the word “this” unfolds (Figure 5).38The slight crescendo that Fitzgerald adds to the word “this” impacts the amplitude envelope of the note, which in turn influences the position of the P-centre; for more on how the relationships between amplitude envelopes and onsets impact P-centre locations, see Danielsen et al. (2019).

Figure 5: Analysis of Fitzgerald’s opening phrase of “There Will Never Be Another You,” with delayed P-centre on the word “this.”

The delayed P-centre is likely due to Fitzgerald’s clean enunciation of the words “nights like this:” while syllable onsets are usually understood to correlate with the onset of a vowel sound, Rudi Villing (2010) writes that “manipulating the initial consonant duration (or the temporal onset of the vowel relative to the syllable onset) appears to have a strong effect on the P-centre” (24). Fitzgerald’s elongation of the first consonant of the word “this” delays the vowel sound, creating the impression that the note’s onset is significantly behind the beat.39For more on the relations between vowels, consonants, syllables, and P-centres, see Villing (2010, pp. 20–46). That clear articulation is a key part of her influential vocal style, so it is unsurprising that she does not sacrifice enunciation for rhythmic precision. Rather than delay the onset of the final note (“this”) substantially, Fitzgerald elongates the note, taking slightly longer to get through the word “this” but still beginning the note very near the downbeat. In doing so, the main pitch content of “this” appears to arrive slightly late, shifting the P-centre back. Because the articulation is so close to the downbeat, and because the P-centre delay signifies Fitzgerald’s effort to arrive at the downbeat on time, it is unlikely that this delay will be perceived as a displacement; it is more likely to be heard as a very minor microtiming delay. Note also that Fitzgerald’s voice interacts with the ongoing two-feel provided by the rhythm section: Bassist Keter Betts and drummer Mickey Roker emphasize beats 1 and 3, perhaps influencing Fitzgerald’s choice not to overtly delay the arrival of “this” on the downbeat.

As a vocalist working at an even faster tempo, Vaughan faces the same problem as Fitzgerald—needing to enunciate “nights like this” in quarter notes at a brisk tempo— but her solution to this problem is different. While her enunciation is perhaps not quite as clean as Fitzgerald’s, she nonetheless articulates each word clearly. In order to accomplish this, she delays the onset of the E-flat and F—the words “like this”—giving her more time to finish enunciating each word. Because the tempo, which hovers around 275 bpm, is quicker than that of Fitzgerald’s rendition (~205 bpm), it necessitates even more delay relative to the quarter-note tactus. Indeed, her onset delays are late enough that they may be interpreted not as expressive timing but as a metered cross-rhythmic 3-against-2 figure, as shown in Figure 6. Neither of these interpretations is necessarily more correct than the other. Instead, both readings mutually enrich one another.40This type of hearing, where multiple interpretations work together to reveal a multifaceted analysis of a musical excerpt, is discussed in more detail in Chris Stover (2013) and requires listeners to exercise what Ingrid Monson (2008) terms “perceptual agency.” The relationship between these two interpretations is essentially a “chicken or egg” situation: Vaughan’s delays may have started for practical reasons—at this tempo, it would be difficult to enunciate the words expressively and still land on the downbeat comfortably—but Vaughan possibly will also have recognized the opportunity to create an engaging 3-against-2 cross-rhythm as these delays unfolded. The ambiguity between these interpretations, I believe, is not an interpretive problem but an aesthetic solution: the ambiguity is the message, a sonic byproduct of the fast-unfolding improvisational process that rewards close attention and anticipation. This can be read as a process of becoming (indicated by the symbol ⇒ in Figure 6), a rhythmic analogue to the notion of “fixing a wrong note,” whereby a so-called “wrong” pitch is creatively contextualized in order to solve an improvisational dilemma.41The becoming symbol (⇒) is introduced by William Caplin (1998, p. 47) to describe “retrospective reinterpretation of formal function” and is developed further in Schmalfeldt (2011). While the symbol is often associated with accounts of formal function, the concepts it is used to evoke—namely, becoming and retrospective reinterpretation—are not unique to the perception of form. Indeed, Caplin notes that in some of his analyses, “the same symbol indicates retrospective reinterpretations of harmony, tonality, and cadence” (1998, p. 265). To hear these interpretations as being processually, dialogically worked out in the improvisational moment is a richer musical experience than hearing one or the other in isolation. To fail to hear this dialogic relationship is to arguably miss out on part of the transformational, Signifyin(g) aesthetic that buttresses Vaughan’s performance.

Figure 6: Two complementary analyses of Vaughan’s opening phrase of “There Will Never Be Another You.”

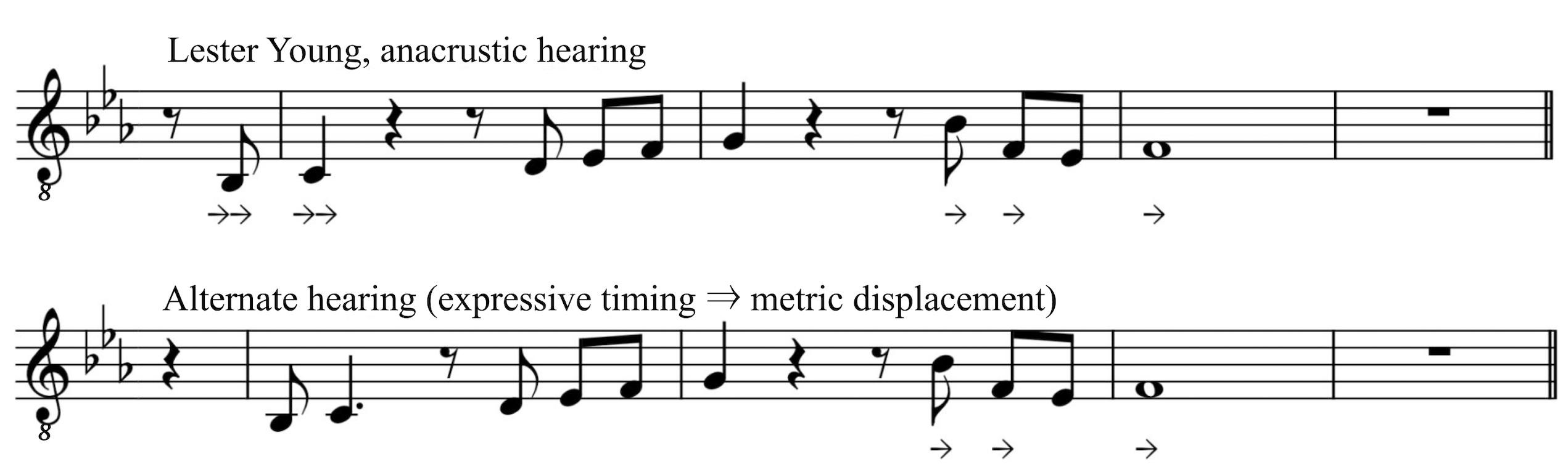

A similar situation unfolds in Lester Young’s rendition, this time at the beginning of the phrase. His initial pair of onsets are significantly delayed behind the beat, represented in the top staff of Figure 7 with two arrows below each note indicating this marked delay. This excerpt can likewise be heard in multiple ways.42Indeed, the slow tempo and languid phrasing of Young’s rendition afford many possible interpretations. I only account here for the interpretations that I hear most readily. If heard as expressive timing, the anacrusis–downbeat pairing is preserved, with downbeats heard as the target of each brief segment of the phrase. If heard as metric displacement, shown in the lower half of Figure 7, that characteristic anacrustic gesture is replaced by a strong downbeat emphasis.43Dexter Gordon’s displacement of the tune’s opening note is also delayed such that it may be interpreted as starting on the downbeat, potentially enacting a similar re-interpretive process as listeners discern the unfolding metric environment. Notably, Gordon plays this melodic segment in exactly the same way on a live date recorded three years later. Once again, we do not need to choose one interpretation over the other, as they may be heard in dialogue with one another, being worked out processually in real time as the improvisation unfolds. Young is well known for his behind-the-beat expressive timing, so dismissing the bottom interpretation in Figure 7 would seem to ignore the trends that govern his idiosyncratic style, as well as the anacrustic thrust of the tune’s opening as it is typically played. But we should not dismiss the anacrustic interpretation in Figure 7 either, as not all of his onset delays are so extensive as to bleed into the next beat. Hearing this moment as “expressive timing ⇒ metric displacement” allows each interpretation to enrich the other and highlights the process of ongoing reinterpretation that listeners might experience as this utterance unfolds.

Figure 7: Two readings of Young’s opening phrase of “There Will Never Be Another You,” with timing discrepancies indicated by arrows.

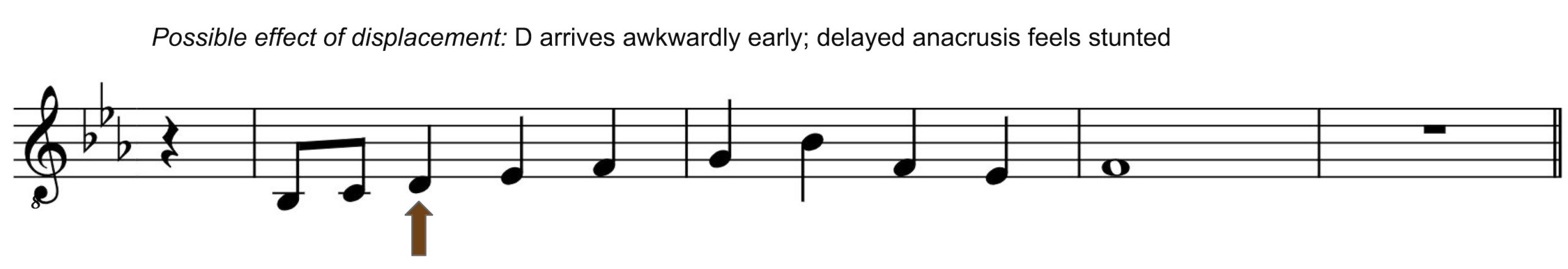

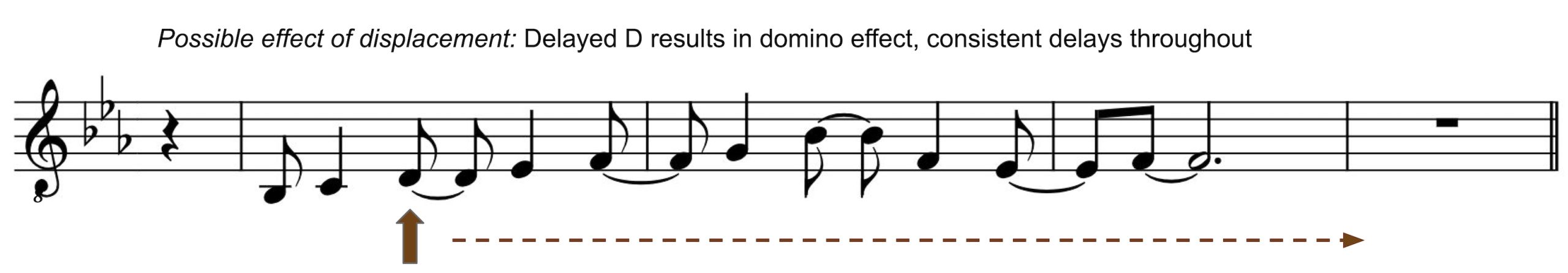

Hearing Young’s performance dialogically can also help us to make sense of the large gap between the onsets of the second and third notes, which produce groupings that are notably at odds with the words of the song (“there will—be many o—ther nights like this”).44While some instrumentalists take into consideration the phrasing implied by the words of a tune, many instrumentalists simply ignore the words and treat the melody more loosely, allowing for greater transformation and ornamentation. If the delayed onsets of B-flat and C were to simply continue to D where it usually falls—somewhere around beat 2—Young might have wound up with one of a number of less-than-ideal scenarios. If D lands on beat 2 or even the “and” of 2 (Figure 8), we might feel that the note was rushed; those first two notes were so late that we might expect more of the phrase to be delayed. Alternatively, if the D is simply delayed (Figure 9), a domino effect might lead to the remainder of the line being delayed, which in turn risks untethering the theme from the groove.45Because the delays would be consistent in this case, the rhythms would suggest to listeners two distinct pulses that are misaligned, resulting in displacement dissonance (see Krebs 1999, pp. 33–36). Instead, Young leaves a brief gap and shortens each of the remaining notes in the measure into an anacrustic motive, which continues again into the next bar. Young’s dialogic “expressive timing ⇒ metric displacement” therefore has ramifications that affect the entire phrase. Indeed, these ramifications extend to the next phrase (transcribed in Figure 10), which features nearly identical spacing despite the unambiguous anacrusis and clear arrival of E-flat on the downbeat. When the original rising line of mm. 1–4 reappears in mm. 17–20 in the second A section (transcribed in Figure 11), Young once again begins with B-flat on the downbeat, but opts for a different spacing of the remaining notes, focusing on triplets rather than an anacrustic motive. By hearing this new interpretation of the melody in dialogue with the opening interpretation, we might hear the opening “expressive timing ⇒ metric displacement” in m. 1 as germinal to the decision to begin m. 17 on the downbeat.

Figure 8: A recomposition of Young’s opening phrase of “There Will Never Be Another You,” where the metric displacements at the beginning of the measure continue into a standard rendition of the melody.

Figure 9: A recomposition of Young’s opening phrase of “There Will Never Be Another You,” where the metric displacements applied to the first two notes continue throughout the entire phrase.

Figure 10: A transcription of Young’s performance of “There Will Never Be Another You,” mm. 5–8 featuring a similar motivic spacing to mm. 1–4.

Figure 11: A transcription of Young’s performance of “There Will Never Be Another You,” mm. 17–20 with divergent spacing but similarly beginning with B-flat on the downbeat.

Case Study 2: Cécile McLorin Salvant’s recording of “I Didn’t Know What Time It Was”

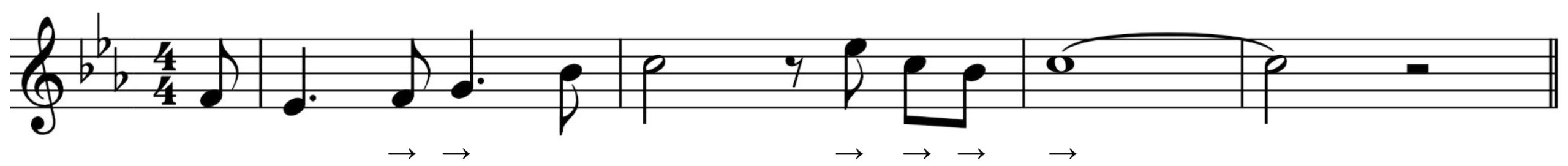

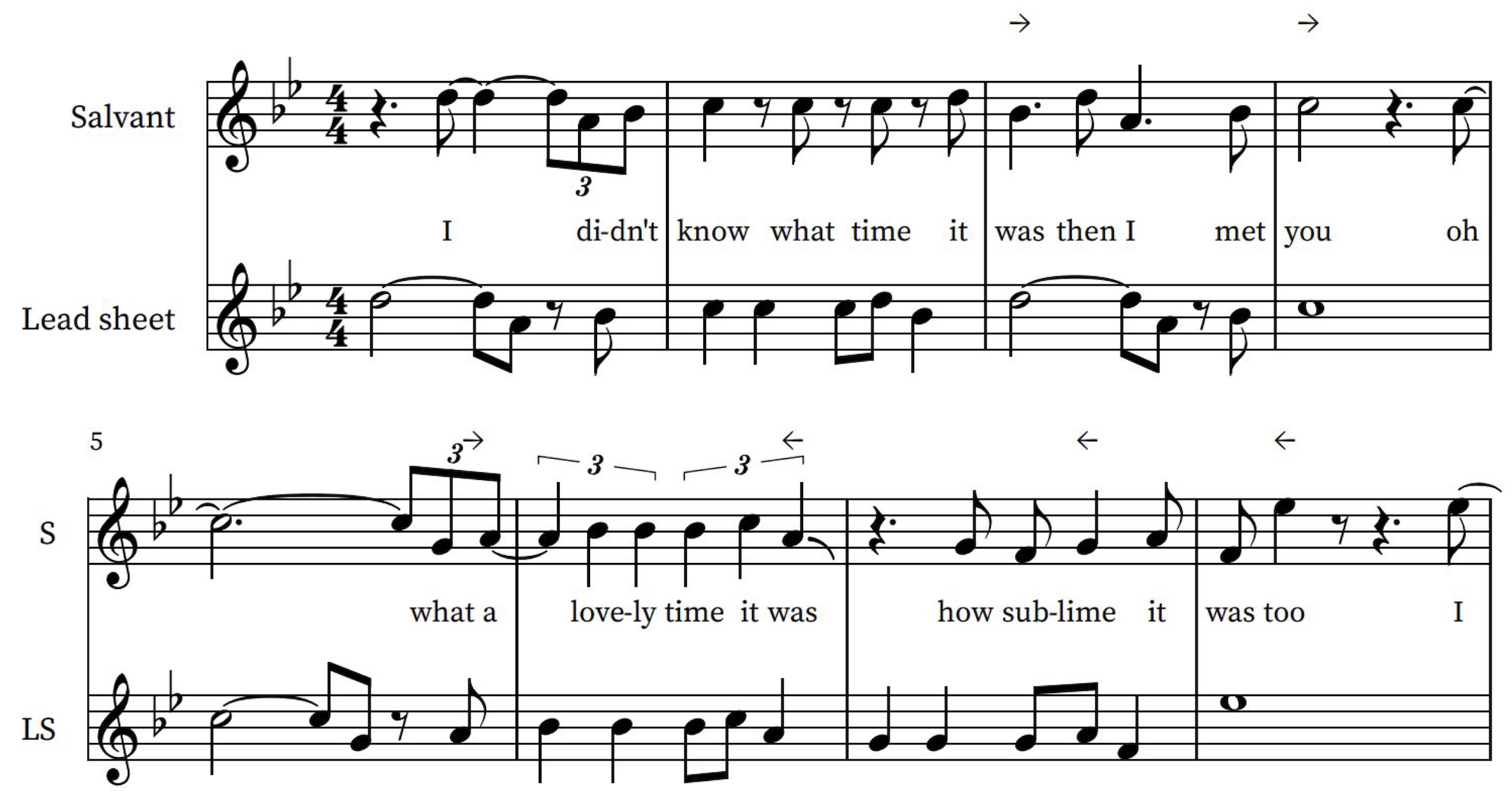

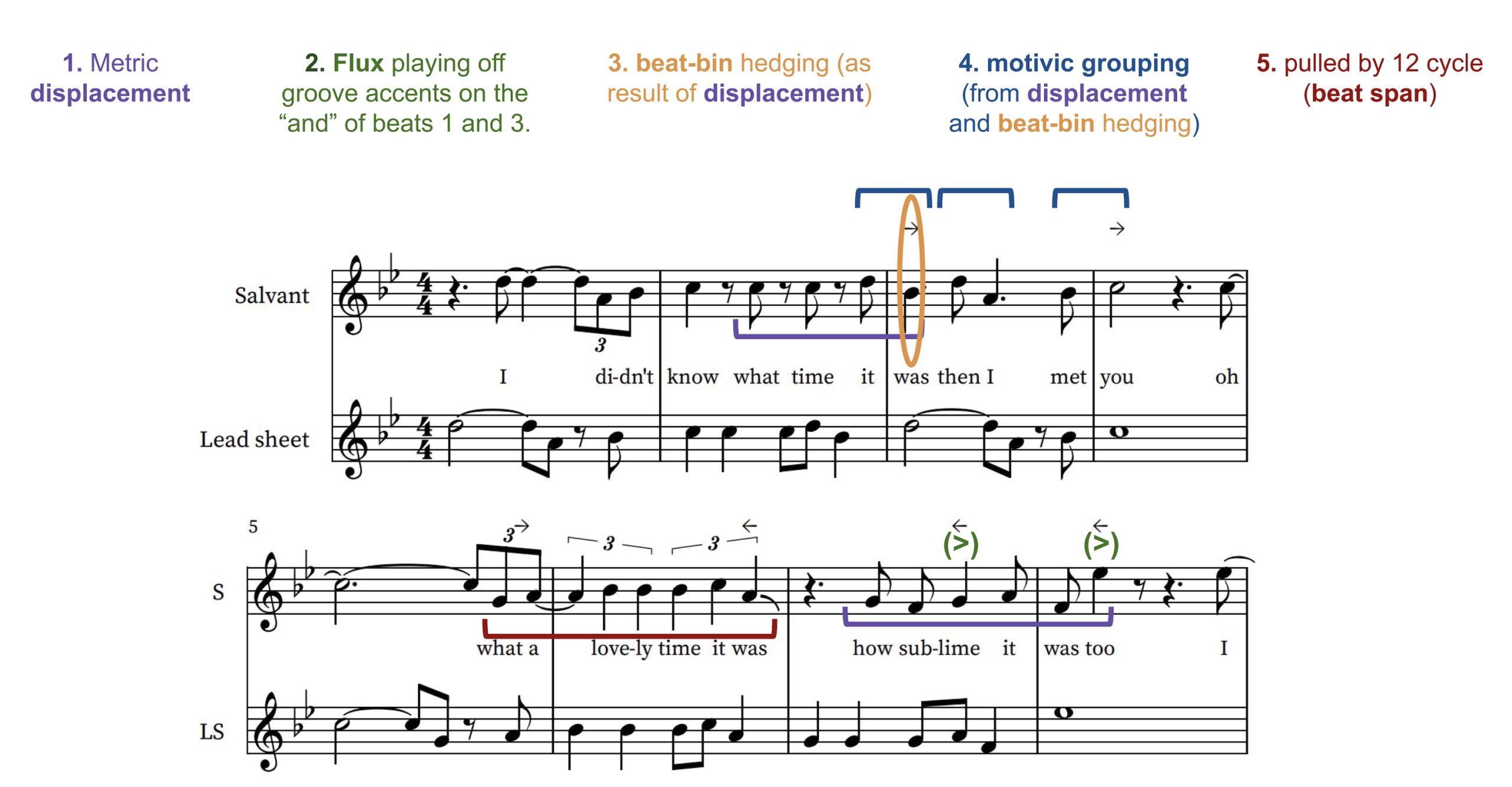

Although negotiation between expressive timing and transformation is a crucial part of most jazz performance—and perhaps especially jazz singing— the celebrated singer Cécile McLorin Salvant is especially adept at walking the tightrope between these categories. Her recording of Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart’s “I Didn’t Know What Time It Was,” from her 2013 album WomanChild, is instructive. At first blush, her interpretation of the melody may seem as though it is consistently delayed. This effect is complicated by pianist Aaron Diehl and bassist Rodney Whitaker playing only on the “ands” of beats 1 and 3, which in turn play off the clear backbeat on beats 2 and 4 that drummer Herlin Riley provides with his hi-hat. A transcription of the first A section of her performance appears in Figure 12, along with a typical lead-sheet rendering of the head melody. Her performance can be heard in Audio Example 6. Although this lead-sheet rendering helps to orient Salvant’s transformations, it is important to remember that her utterances are not heard against an idealized lead sheet but rather against a listener’s referent, which is informed by their familiarity with various versions of the tune.

Figure 12: A transcription of Cécile McLorin Salvant’s recording of the opening phrase of “I Didn’t Know What Time It Was,” compared against a typical lead sheet rendering of the melody.

Media 6: Excerpt of Cécile McLorin Salvant’s recording of the opening phrase of “I Didn’t Know What Time It Was.” Listen to Media 6.

There are several techniques that Salvant uses to interpret the tune’s melody; these techniques appear as annotations in Figure 13. The first of these, labelled annotation 1 and coloured purple, is metric displacement, where a segment of the melody is displaced by a certain number of beats.46Metric displacement in jazz improvisation is discussed in more detail in Waters (1996). The opening A section features two notable metric displacements, the first by an eighth note and the second by a dotted quarter note, although both displacements are affected over time by what Benadon (2009a) terms “flux” transformations, “time warps” in which the passages slightly accelerate or decelerate, resulting in variable onset displacements. By the end of the latter segment’s displacement (“how sublime it was too”), the final E-flat arrives only an eighth note late, notably coinciding with the accompanying rhythm section’s continuous accents on the “ands” of beats 1 and 3 (labelled annotation 2 and coloured green). At the end of the earlier metric displacement in mm. 2–3, the arrival of B-flat is slightly delayed, though still squarely within the beat bin of the downbeat of m. 3. Salvant’s hedging within the beat bin (labelled annotation 3 and coloured gold) allows for a more naturalistic phrasing of the words while leaving more space for her voice to be heard than if she had arrived right on the perceptual centre of the downbeat. This hedging is also responsible for a domino effect: by the time Salvant has finished the word “was,” the next word, “then,” is notably late. Perhaps in order to avoid an awkwardly rushed arrival of the next sub-phrase, she takes the anacrustic motive from “it was” and repeats it with a dotted rhythm for “then I” and “met you,” emphasizing beats 1 and 3 in each case. This motivic grouping (labelled annotation 4 and coloured blue) simultaneously accomplishes two things: first, it anchors her melody back into the groove after the metric displacement and beat-bin hedging; second, it continuously differentiates her voice from the syncopated groove accents on the “ands” of beats 1 and 3.

Figure 13: An annotated transcription of Cécile McLorin Salvant’s recording of the opening phrase of “I Didn’t Know What Time It Was.”

In measures 5–6, a different kind of flux-displacement takes place, whereby the onsets of the entire segment are flattened out to be roughly evenly spaced within a quarter-note triplet grid. I hear this transformation in dialogue with many similar evened-out events in Afro-Diasporic musics and find Chris Stover’s (2009) notion of “beat span” to hold explanatory power here. Stover, in a co-authored article comparing beat spans to Danielsen’s beat bins and Mats Johansson’s notion of rhythmic tolerance, writes that the metric grids of many African and Afro-Diasporic musics are always in flux by virtue of “co-extensive triple and quadruple subdivisions of a basic four-count metric structure—which conspire to pull played events in one temporal direction or another as a performance unfolds” (Danielsen, et al. 2023, p. 23). Utterances may therefore be understood as negotiating a space defined by both a 12-cycle and a 16-cycle. For example, in 4/4, quarter notes divided into triplets generate a 12-cycle, while sixteenth notes generate a 16-cycle. I hear Salvant’s quarter-note triplets in m. 6 (labelled annotation 5 and coloured red) as leaning into the pull of the 12-cycle, engendered here by the underlying 12-cycle that helps produce the swing feel, and which she clearly articulates in the fourth beat of both mm. 1 and 5. In order to make sense of Salvant’s performance, then, we must hear her improvisational choices as spinning out a nuanced dialogue between Salvant, the tune, the arrangement, the rhythm section, stylistic expectations, and other expectations engendered dynamically as the improvisation unfolds.

At a moment-to-moment level, then, a constant back-and-forth between expressive timing and transformation is responsible for Salvant’s distinctive phrasing. On a larger scale, there is also a dialogic relation between segments of her melody. The lines “I didn’t know what time it was” (mm. 1–3) and “oh, what a lovely time it was” (mm. 5–6) feature the same number of syllables and are diatonic transpositions of one another; Salvant’s decision to contract the rhythms in mm. 5–6 may be a deliberate choice to create contrast with the expanded rhythms in mm. 1–3.47Benadon (2024, pp. 77–78) argues that not all rhythms can be said to be derived from an underlying template, and that if this view is abandoned, we can examine how various renditions of the same or similar melodies are constructed based on balancing expansion and contraction across a phrase. Likewise, the similarities between these segments invite comparison from a listener’s perspective, with the earlier segment likely to colour one’s perception of the later segment.

Conclusion

Through these examples, we can see that while expressive timing and thematic transformation are arguably distinct in the abstract, jazz musicians playfully exploit the ambiguity between them in order to generate rhythmic interest in the improvisational moment. This technique is common in a great deal of jazz improvisation, but it is especially salient when a recognizable theme is being transformed. Although this article has not engaged with styles outside that of mainstream jazz improvisation, this dialogic, processual working-out of microtiming and thematic variation can be found in many other musics that feature flexible thematic ontology and some degree of rhythmic freedom in performance.

Still, plenty of questions remain to be answered. What kinds of psychological limitations shape the interpretation of these rich moments? To what extent are improvisers consciously aware of this interplay? How might different swing ratios and tempos affect perceptions of timing versus transformation? And how, if at all, do these processes change when applied not to recognizable themes but to the melodic inventions typical of jazz solos? Addressing these and similar questions will help to further disentangle the improvisational rhythmic processes that make performances of jazz standards so lively and memorable.

Bibliography

Agawu, Kofi (2006), “Structural Analysis or Cultural Analysis? Competing Perspectives on the ‘Standard Pattern’ of West African Rhythm,” Journal of the American Musicological Society, vol. 59, no 1, pp. 1–46.

Ashley, Richard (2002), “Do[n’t] Change a Hair for Me. The Art of Jazz Rubato,” Music Perception, vol. 19, no 3, pp. 311–332.

Assis, Paulo de (2018), “Virtual Works—Actual Things,” in Paulo de Assis (ed.), Virtual Works—Actual Things. Essays in Music Ontology, Leuven, Leuven University Press, pp. 19–44.

Benadon, Fernando (2024) Swinglines. Rhythm, Timing, and Polymeter in Musical Phrasing, New York, Oxford University Press.

Benadon, Fernando (2009a), “Time Warps in Early Jazz,” Music Theory Spectrum, vol. 31, no 1, pp. 1–25.

Benadon, Fernando (2009b), “Gridless Beats,” Perspectives of New Music, vol. 47, no 1, pp. 135–164.

Benadon, Fernando (2006), “Slicing the Beat. Jazz Eighth-Notes as Expressive Microrhythm,” Ethnomusicology, vol. 50, no 1, pp. 73–98.

Born, Georgina (2005), “On Musical Mediation. Ontology, Technology, and Creativity,” Twentieth-Century Music, vol. 2 no 1, pp. 7–36.

Bowen, José A. (1993), “The History of Remembered Innovation. Tradition and its Role in the Relationship between Musical Works and their Performances,” The Journal of Musicology, vol. 11 no 2, pp. 139–73.

Butterfield, Matthew (2010), “Participatory Discrepancies and the Perception of Beats in Jazz,” Music Perception, vol. 27, no 3, pp. 156–176.

Butterfield, Matthew (2006), “The Power of Anacrusis. Engendered Feeling in Groove-Based Musics,” Music Theory Online, vol. 12, no 4.

Caplin, William (1998), Classical Form. A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, New York, Oxford University Press.

Câmara, Guilherme Schmidt, and Anne Danielsen (2019), “Groove,” in Alexander Rehding and Steven Rings (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Critical Concepts in Music Theory, New York, Oxford University Press, pp. 271–294.

Cook, Nicholas (1999), “Analyzing Performance and Performing Analysis,” in Nicholas Cook and Mark Everist (eds.), Rethinking Music, Oxford, Oxford University Press, pp. 239–261.

Danielsen, Anne (2018), “Pulse as Dynamic Attending. Analysing Beat Bin Metre in Neo Soul Grooves,” in Ciro Scotto, Kenneth M. Smith, and John Brackett (eds.), The Routledge Companion to Popular Music Analysis. Expanding Approaches, New York, Routledge, pp. 179–189.

Danielsen, Anne (2015), “Metrical Ambiguity or Microrhythmic Flexibility? Analysing Groove in ‘Nasty Girl’ by Destiny’s Child,” in Ralf von Appen, Andre Doehring, and Allan F. Moore (eds.), Song Interpretation in 21st-Century Pop Music, Farnham, Ashgate, pp. 53–72.

Danielsen, Anne, Mats Johansson, and Chris Stover (2023), “Bins, Spans, and Tolerance. Three Theories of Microtiming Behavior,” Music Theory Spectrum, vol. 45, no 2, pp. 181–198.

Danielsen, Anne, Justin London, Kristian Nymoen et al. (2019), “Where Is the Beat in That Note? Effects of Attack, Duration and Frequency on the Perceived Timing of Musical and Quasi-Musical Sounds,” Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, vol. 45, no 3, pp. 402–418.

Davis, Whitney (1996), Replications. Archaeology, Art History, Psychoanalysis, University Park, Penn State University Press.

Floyd, Samuel A., Jr. (1991), “Ring Shout! Literary Studies, Historical Studies, and Black Music Inquiry,” Black Music Research Journal, vol. 11, no 2, pp. 265–287.

Folio, Cynthia and Robert W. Weisberg (2006), “Billie Holiday’s Art of Paraphrase. A Study in Consistency,” in New Musicology, Poznan, Poznan Press, pp. 247–275.

Gates, Jr., Henry Louis (1988), The Signifying Monkey. A Theory of Afro-American Literary Criticism, New York, Oxford University Press.

Givan, Benjamin (2016), “Rethinking Interaction in Jazz Improvisation,” Music Theory Online, vol. 22, no 3, https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.16.22.3/mto.16.22.3.givan.html.

Givan, Benjamin (2007), “Apart Playing. McCoy Tyner and ‘Bessie’s Blues,’” Journal of the Society for American Music, vol. 1, no 2, pp. 257–280.

Hudson, Richard (1994), Stolen Time. The History of Tempo Rubato, Oxford, Clarendon Press.

Hodson, Robert (2007), Interaction, Improvisation, and Interplay in Jazz, New York, Routledge.

Huang, Hao, and Rachel Huang (1994–1995), “Billie Holiday and Tempo Rubato. Understanding Rhythmic Expressivity,” Annual Review of Jazz Studies, vol. 7, pp. 181–200.

Iyer, Vijay (2002), “Embodied Mind, Situated Cognition, and Expressive Microtiming in African-American Music,” Music Perception, vol. 19, no 3, pp. 387–414.

Iyer, Vijay (1998), Microstructures of Feel, Macrostructures of Sound. Embodied Cognition in West African and African-American Musics, Ph.D. diss., University of California, Berkeley.

Kane, Brian, (2024), Hearing Double. Jazz, Ontology, Auditory Culture, New York, Oxford University Press.

Keil, Charles (1987), “Participatory Discrepancies and the Power of Music,” Cultural Anthropology, vol. 2, no 3, pp. 275–283.

Koetting, James T. (1970), “Analysis and Notation of West African Drum Ensemble Music.” Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology, vol. 1, no 3, pp. 115–146.

Krebs, Harald (1999), Fantasy Pieces. Metrical Dissonance in the Music of Robert Schumann, New York, Oxford University Press.

Leong, Daphne (2011), “Generalizing Syncopation. Contour, Duration, and Weight,” Theory and Practice, vol. 36, pp. 111–150.

Leong, Daphne (2000), “A Theory of Time-Spaces For the Analysis of Twentieth-Century Music. Applications to the Music of Bela Bartok,” Ph.D. diss., University of Rochester.

Lerdahl, Fred and Ray Jackendoff (1983), A Generative Theory of Tonal Music, Cambridge, MIT Press.

Levin, Robert D. (1992), “Improvised Embellishments in Mozart’s Keyboard Music,” Early Music, vol. 20, no 2, pp. 221–233.

London, Justin (2004), Hearing in Time. Psychological Aspects of Musical Meter, New York, Oxford University Press.

Love, Stefan Caris (2017), “An Ecological Description of Jazz Improvisation,” Psychomusicology. Music, Mind, and Brain, vol. 27, no 1, pp. 31–44.

Love, Stefan Caris (2016), “The Jazz Solo as Virtuous Act,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol. 74, no 1, pp. 61–74.

Michaelsen, Garrett (2019), “Making ‘Anti-Music’. Divergent Interactional Strategies in the Miles Davis Quintet’s The Complete Live at the Plugged Nickel 1965,” Music Theory Online, vol. 25, no 3, https://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.19.25.3/mto.19.25.3.michaelsen.html.

Michaelsen, Garrett, (2013), “Analyzing Musical Interaction in Jazz Improvisations of the 1960s,” Ph.D. diss., Indiana University.

Morton, John, Steve Marcus, and Clive Frankish (1976), “Perceptual Centers (P-Centers),” Psychological Review, vol. 83, no 5, pp. 405–408.

Monson, Ingrid (2008), “Hearing, Seeing, and Perceptual Agency,” Critical Inquiry, vol. 34, no 2, pp. 36–58.

Monson, Ingrid (1994), “Doubleness and Jazz Improvisation. Irony, Parody, and Ethnomusicology,” Critical Inquiry, vol. 20, no 2, pp. 283–313.

Nketia, J.H. Kwabena (1974), The Music of Africa, New York, W.W. Norton.

Norgaard, Martin (2011), “Descriptions of Improvisational Thinking by Artist-Level Jazz Musicians,” Journal of Research in Music Education, vol. 59, no 2, pp. 109–127.

Ohriner, Mitchell (2019), “Expressive Timing,” in Alexander Rehding and Steven Rings (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Critical Concepts in Music Theory, New York, Oxford University Press, pp. 369–394

Polak, Rainer (2017), “The Lower Limit for Meter in Dance Drumming from West Africa,” Empirical Musicology Review, vol. 12, no 3–4, pp. 205–226.

Pressing, Jeff (1988), “Improvisation. Methods and Models,” in John Sloboda (ed.), Generative

Processes in Music. The Psychology of Performance, Improvisation, and Composition, Oxford, Clarendon Press, pp. 129–178.

Pressing, Jeff (1984), “Cognitive Processes in Improvisation,” in W. Ray Crozier and Anthony J. Chapman (eds.), Cognitive Processes in the Perception of Art, Amsterdam, North-Holland, pp. 345–363.

Salley, Keith and Daniel T. Shanahan (2016), “Phrase Rhythm in Standard Jazz Repertoire. A Taxonomy and Corpus Study,” Journal of Jazz Studies, vol. 11, no 1, pp. 1–39.

Schmalfeldt, Janet (2011), In the Process of Becoming. Analytical and Philosophical Perspectives on Form in Early Nineteenth-Century Music, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Smither, Sean (2024), “Referents in the Palimpsests of Jazz. Disentangling Theme from Improvisation in Recordings of Standard Jazz Tunes,” Music Theory Online, vol. 30, no 3, https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.24.30.3/mto.24.30.3.smither.html.

Smither, Sean (2021), “All the Things Tunes Are. Avant-Textes and Referents in Jazz Improvisation,” Jazz Perspectives, vol. 13, no 2, pp. 1–27.

Stover, Chris (2017), “Time, Territorialization, and Improvisational Spaces,” Music Theory Online, vol. 23, no 1, https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.17.23.1/mto.17.23.1.stover.html.

Stover, Chris (2013), “Analysis as Multiplicity,” Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy, vol. 27, pp. 111–142.

Stover, Chris (2009), A Theory of Flexible Rhythmic Spaces for Diasporic West African Music, Ph.D. diss., University of Washington.

Taruskin, Richard (1994), Text and Act. Essays on Music and Performance, New York, Oxford University Press.

Temperley, David (2008), “Hypermetrical Transitions,” Music Theory Spectrum, vol. 30, no 2, pp. 305–325.

Villing, Rudi C. (2010), “Hearing the Moment. Measures and Models of the Perceptual Centre,” Ph.D. diss., National University of Ireland Maynooth.

Walser, Robert (1993), “Out of Notes. Significance, Interpretation, and the Problem of Miles Davis,” The Musical Quarterly, vol. 77, no 2, pp. 343–365.

Waterman, Christopher A. (1995), “Response to Charles Keil, ‘The Theory of Participatory Discrepancies. A Progress Report,’” Ethnomusicology, vol. 39, no 1, pp. 92–94.

Waters, Keith (1996), “Blurring the Barline. Metric Displacement in the Piano Solos of Herbie Hancock,” Annual Review of Jazz Studies, vol. 8, pp. 19–37.

White, Christopher (2023), The Music in the Data. Corpus Analysis, Music Analysis, and Tonal Traditions, New York, Routledge.

Zbikowski, Lawrence (2002), Conceptualizing Music. Cognitive Structure, Theory, and Analysis, New York, Oxford University Press.

Discography

Baker, Chet (1954), Chet Baker Sings, Pacific Jazz Records PJLP-11.

Fitzgerald, Ella ([1979] 2013), North Sea Jazz Legendary Concerts, Bob City BCCD13.010.

Gordon, Dexter ([1967] 1988), Body and Soul, Black Lion BLP 60118.

Salvant, Cécile McLorin (2013), WomanChild, Mack Avenue MAC1072LP.

Vaughan, Sarah (1973), “Live” in Japan, Mainstream Records MRL 2 401.

Young, Lester with the Oscar Peterson Trio ([1952] 1954), Lester Young with the Oscar Peterson Trio, Norgran Records MGN 5/6/1054.

| RMO_vol.12.2_Smither |

Attention : le logiciel Aperçu (preview) ne permet pas la lecture des fichiers sonores intégrés dans les fichiers pdf.

Citation

- Référence papier (pdf)

Sean R. Smither, « Expressive Timing or Thematic Transformation? Onset Displacement in Performances of Jazz Standard Melodies », Revue musicale OICRM, vol. 12, no 2, 2025, p. 26-51.

- Référence électronique

Sean R. Smither, « Expressive Timing or Thematic Transformation? Onset Displacement in Performances of Jazz Standard Melodies », Revue musicale OICRM, vol. 12, no 2, 2025, mis en ligne le 13 mai 2025, https://revuemusicaleoicrm.org/rmo-vol12-n2/displacement-in-performances-of-jazz-standard-melodies/, consulté le…

Auteur

Sean R. Smither, The Juillard School / Mannes School of Music

Sean Smither is on the faculty at the Juilliard School, where he teaches jazz theory and analysis, and at Mannes School of Music, where he teaches courses in classical music theory and analysis. He received his Ph.D. in music theory from Rutgers University and also holds a degree in jazz performance from the New School. His research focuses on improvisation, the analysis of jazz, music ontology, and musical time. He serves as co-chair of the Society for Music Theory’s Jazz Interest Group and was previously chair of the Society for Music Theory’s Improvisation Interest Group.

Notes

| ↵1 | For more on the organization of hypermeter and hypermetric emphasis, see Lerdahl and Jackendoff (1983, 69–100), Waters (1996), Temperley (2008), and Salley and Shanahan (2016). |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | Expressive timing refers to small changes in the onset positions and/or durations of notes; for an overview of expressive timing and its history, see Ohriner (2019). Both expressive timing and thematic transformation are defined and discussed in more detail below. |

| ↵3 | The so-called “Great American Songbook” era includes works by composers such as Richard Rodgers, Jerome Kern, George Gershwin, and Harold Arlen. Later melodies from the bebop era onward are notably more specific in their rhythms, though this is not to say that later melodies are not also transformed considerably. |

| ↵4 | In each transcription, determinations of microtiming were made by comparing the onsets of the lead instrumentalist or singer to those of the rhythm section, particularly the bass and drums. For more on the perception of beats in jazz, particularly with regard to discrepancies within the rhythm section, see Butterfield (2010). |

| ↵5 | For more on the improvisational process and the factors that render it opaque to not only researchers but improvisers themselves, see Pressing (1984, 1988) and Norgaard (2011). For more on the ways that improvisational contexts relate to time, see Stover (2017). |

| ↵6 | This feedback loop is theorized in Hodson (2007) and Michaelsen (2013). |

| ↵7 | Anne Danielsen (2015, p. 54) argues that the notion of “expression” in most descriptions of microtiming is a relic of an outdated divide between structure and expression. While the term certainly reflects this mapping, I continue to use the term in this study because I find that such timing in jazz is frequently read by listeners as expressive, especially when it is marked and understood as explicitly transformational, not just part of the “participatory discrepancies” (Keil 1987) that animate an ongoing groove. It is therefore an evocative term that can refer to a particular microtiming strategy, rather than as a catchall for timing discrepancies more generally. |

| ↵8 | Leong (2000, p. 65) refers to IOIs in this sense as “interval duration” (idur). |

| ↵9 | Metric expressive timing and rubato are sometimes coterminous, although some implementations of metric expressive timing may not be severe enough to be considered rubato. Hudson (1994, p. 1) describes two types of rubato; his “early” rubato encompasses what I call rhythmic expressive timing, while the “later” type mostly resembles metric expressive timing. For more discussion on the relationship between these conceptions as they apply to jazz, see Ashley (2002) and Benadon (2009b). |

| ↵10 | The term “works for performance” is introduced by Stephen Davies (2001) to describe an ontology of musical works in which a score (or equivalent artifact) is used to generate a performance; Davies argues that this ontology is operative for most of the history of Western concert music. |

| ↵11 | As Nicholas Cook (1999) argues, performance choices in Western concert music have often been misconstrued by theorists as emanating from the work rather than the performer, reinforcing the idea that performers have little true agency and simply serve as vessels to communicate the musical work. Still, there can be little doubt that departing in salient ways from a notated score remains rare in Western concert music, even in repertoires where improvisation would historically have been expected; for notable critiques along these lines, see Levin (1992) and Taruskin (1995, especially Chapter 17, pp. 334–346). |

| ↵12 | For more on the constraints and affordances of metric entrainment, see London (2004). |

| ↵13 | Keil’s theorization inspired a number of subsequent studies on participatory discrepancies in jazz, including Prögler (1995), Waterman (1995), Givan (2007), and Butterfield (2010, 2011). |

| ↵14 | Critiquing conventional music-theoretical approaches to microtiming, Benadon characterizes the safety-net approach as follows: “If you sing a note and find you cannot pin it to one layer, try the one below. You may have to go as low as thirty-second notes or even resort to borrowing ternary division, but eventually your note will land on a safety net” (2024, p. 4). |

| ↵15 | The term “microtiming” is introduced in Iyer (1998) and is discussed in detail in Iyer (2002). |

| ↵16 | In groove-based musics, durations still change in the layer of the music that involves expressive timing, but these durations are limited to the part that features expressive timing and are constrained in part by the needs of the groove. If the total duration of the excerpt is to be synchronized with the underlying groove, a stretched duration will need to be complemented by a contracted duration (often a rest) somewhere else, enacting what Hao and Rachel Huang (1994–5) call “dual-track time.” |

| ↵17 | For more on the comparison of virtual reference structures to actualized rhythms, see Danielsen (2015, 2018). Danielsen’s virtual/actual distinction is informed by Gilles Deleuze’s use of the terms; for more on the interplay of the virtual and actual in jazz and improvisation more generally, see Stover (2017). |

| ↵18 | In such a conception, the shortening or lengthening of durations is understood as either a natural consequence of a change of onset position or as a separate interpretive choice altogether. |

| ↵19 | It is important to note that this does not mean that the expressive timing is not intentional. Rather, if a note is perceived as anticipated or delayed via expressive timing, this means that the listener does not hear the note’s metric position as intentionally altered, even if the timing change could potentially be heard as a change in metric position. |

| ↵20 | The notion of a perceptual centre first appears in Morton et al. (1976). P-centres are also closely connected to the notion of beat bins (Danielsen 2018). |

| ↵21 | For more on the relationship between errors, spontaneity, and authenticity in jazz, see Walser (1993). |

| ↵22 | Zbikowski (2002, 201–242) discusses how jazz tunes may be conceptualized as prototypes by adapting aspects of Eleanor Rosch’s theory of categories and prototypes to models of music ontology. |