Virile Condottieri On-screen and Emasculated Heroes

on the Operatic Stage. Portraying Male Protagonists

in Fascist Italy (1931-1937)

Zoey M. Cochran

| PDF | CITATION | AUTEUR |

Abstract

Virility was central to Italian fascist ideology and yet the operas composed and performed in Italy during the 1930s systematically subvert the virility of their heroes both dramatically and musically, revealing a more fraught relationship with fascist ideology than has been suggested until now. A comparison between operas by Gian Francesco Malipiero, Ottorino Respighi, Pietro Mascagni, Ildebrando Pizzetti, and Alfredo Casella on the one hand and films by Alessandro Blasetti, Mario Camerini, and Carmine Gallone on the other, all produced in Italy during the mid-1930s, shows that the absence of male protagonists embodying fascist ideals of virility is confined to opera. I suggest that the failure of these operas to present virile male protagonists partly stems from a confrontation between opera and film. Indeed, the emergence of sound films and cinema’s privileged position within the Fascist regime forced opera to redefine itself as an art form in relationship to film.

Keywords: masculinity; fascist virility; opera and film; characterization of male protagonists; Ancient Roman subjects.

Résumé

La virilité est au cœur de l’idéologie fasciste ; pourtant, les opéras composés et représentés en Italie pendant les années 1930 subvertissent systématiquement la virilité des héros sur les plans musical et dramatique, révélant que ces opéras entretenaient une relation bien plus complexe avec l’idéologie fasciste qu’on ne l’a affirmé jusqu’à présent. Une comparaison entre les opéras de Gian Francesco Malipiero, Ottorino Respighi, Pietro Mascagni, Ildebrando Pizzetti et Alfredo Casella et les films de Alessandro Blasetti, Mario Camerini et Carmine Gallone, tous produits en Italie pendant les années 1930, démontre que cette absence de protagonistes masculins incarnant les attributs de la virilité fasciste est unique à l’opéra. J’avance que cette absence résulte, entre autres, d’une confrontation entre l’opéra et le cinéma. En effet, l’émergence des films sonores et la position privilégiée du cinéma au sein du régime fasciste porte l’opéra à se redéfinir comme médium face au cinéma.

Mots clés : masculinité ; virilité fasciste ; opéra et cinéma ; caractérisation des protagonistes masculins ; sujets tirés de l’Antiquité romaine.

“Death to tyrants! You be Duce, Bruto! Kill Sesto! Let’s get rid of kings! Death to him! Freedom! To Rome!1“Morte ai tiranni! Sii duce tu, Bruto! Uccidere Sesto! E si caccino i re! Muoia! Libertà! A Roma!” All translations in the article are my own. I would like to thank Christoph Neidhöfer, whose seminar on music and politics first inspired this project, Serge Cardinal, who encouraged me to deepen my reflection on the relationship between opera and film, this journal’s reviewers for their generous comments, as well as the many others who read and commented on previous versions of this research, especially Nina Penner, for her careful editing and invaluable comments.” These words, constituting the final chorus of Ottorino Respighi and Claudio Guastalla’s Lucrezia (Respighi 1936, p. 117-118), can be (and have been) read as both pro- and anti-fascist, depending on which words are the focus – “You be Duce, Bruto” and “to Rome” or “death to tyrants!” and “freedom” (Flamm 2004, p. 334, Stenzl 1990, p. 105)2Indeed, Flamm discusses how Elsa Respighi used this final chorus to defend her husband from accusations of fascism, whereas Stenzl presents the same chorus as an example of fascist propaganda.. Though many works produced during the Fascist regime present different degrees of ambiguity – as numerous studies of cultural productions of the fascist ventennio have shown – this obliquity has often been ignored in the case of the operas composed and performed in Italy during the 1930s3The contradictions of fascist ideology and the ambiguities and ambivalence of cultural productions under the Fascist regime have been explored in an increasing number of studies, especially in the last twenty years, by film scholars (Ben-Ghiat 2005, Landy 1986 and 1998, Reich 2002, Ricci 2008), literary scholars (Frese Witt 2001, Pickering-Iazzi 1997), art historians (Champagne 2013), and cultural historians (De Grazia 1992, Spackman 1996, Stone 1998). For an overview of the historiographical debates concerning fascism in Italy, see De Felice 1998..

Following Fiamma Nicolodi’s interpretation of the operas composed by Pietro Mascagni (Nerone), Ottorino Respighi (La fiamma and Lucrezia), Gian Francesco Malipiero (La favola del figlio cambiato, Giulio Cesare, and Antonio e Cleopatra), Ildebrando Pizzetti (Orsèolo), and Alfredo Casella (Il deserto tentato) between 1931 and 1937, musicological studies have brushed these operas aside as embarrassing expressions of fascist ideology (Nicolodi 1984 and 2004, Stenzl 1990, Waterhouse 1999)4Waterhouse explains that “Malipiero’s three operas of these years [1934-1940] are usually regarded (not without reason, though one must be careful not to underestimate them) as forming a relatively unimportant interlude in his theatrical output, in which he strayed even further from his ‘true path’ as a stage composer than he had done in the last act of La favola del figlio cambiato” (Waterhouse 1999, p. 191). Stenzl focuses on the Roman and imperialistic themes of the operas composed during these years (Stenzl 1990, p. 70, 120-123, 134).. Indeed, in her seminal book Musica e musicisti nel ventennio fascista, Nicolodi denounces the operas for endorsing fascist ideology in their subject matter – the staging of Ancient Roman themes, for example – and in their return to “the more obsolete [operatic] models of the past” (Nicolodi 1984, p. 11-12)5“i modelli più obsoleti del passato.”.

In this essay, I argue that the operas discussed by Nicolodi merit closer examination: not only do they present a more fraught relationship with fascist ideology than has been hitherto suggested, but, as I will show, they also express the changing relationship between opera and film at a time when one medium increasingly encroached upon the territory of the other. During the 1930s, the dissemination of sound pictures brought music and singing onto the screen, taking away opera’s final prerogative. This period thus offers an ideal opportunity to investigate the changing relationship between opera and film, as well as the connection of both media to fascist ideology. Indeed, the 1930s saw an increase in the Fascist regime’s involvement in cultural life and propaganda, accentuated by the materialization of Benito Mussolini’s imperialistic ambitions, which culminated in the Italo-Ethiopian War (1935–1936). The implementation of discriminatory laws against Italian Jews (known as the “leggi raziali”) in 1938 and the start of the Second World War the following year brought many changes to the Italian cultural landscape, creating a natural boundary to the scope of this study6Both Lorenzo Benadusi (2012, p. 296) and Ruth Ben-Ghiat (2005) note a strong shift in depictions of masculinity (which will be the focus of this article) during the Second World War..

Studies of the relationship between opera and film tend to focus on the influence of opera on film – how film can be operatic – (Dalle Vacche 1991, Tambling 1987) or on cinematic representations of opera (Citron 2010, Fawkes 2000, Grover-Friedlander 2005). In both cases, the focus remains on film, as though the story of the relationship between opera and cinema can only be told from the perspective of film: how film benefited from opera, how film can reveal new things about opera. Some studies consider the influence of film on opera, but they tend to focus on the musical translation of cinematic techniques7In Opera, Ideology, and Film, for example, Jeremy Tambling likens the elements of continuity and disruption in the operas of Schoenberg and Berg to the cutting and combining of film sequences (Tambling 1987, p. 75-76). Julien Ségol also discusses the renewing aesthetic effect of cinema on opera in Germany in the interwar period (Ségol 2017).. This article proposes to look at the relationship between opera and film from a different perspective, by asking how opera reacted to the growing primacy of film8The recent collection of essays Opéra et cinéma (Picard, Rebel, Ameille and Lécroart 2017) begins to break away from this traditional view of the opera-cinema relationship. Nevertheless, most of its essays still focus on the influence of opera on film (discussed in its first and fourth sections) and on on-screen representations of opera (the subject of its third section). Its second and final sections, exploring the interaction between opera and cinema, principally discuss recent works. My research fits into this new line of inquiry, but focuses on the effect of film on opera’s development as a medium, when both were still vying for popularity..

The changing relationship between opera and film can be gleaned through their differing treatment of male protagonists: whereas virile male protagonists can be found to varying degrees in films of the mid-1930s, the operas created and staged in Italy during the same period systematically subvert the virile hero both dramatically and musically. Virility was central to Italian fascist ideology. Preoccupied with the creation of the “new Italian man,” the Fascist regime repeatedly proposed images and definitions of fascist masculinity incarnated by Mussolini himself. For this reason, the representation of virility on-screen and onstage seems to be the ideal prism through which to view both media’s relationship to fascist ideology and to each other9Indeed, Barbara Spackman has argued that virility was the “principal node of articulation” of fascist rhetoric (Spackman 1996, p. ix). Recent studies on the importance of virility in Fascist Italy support Spackman’s view (Bellassai 2005, Benadusi 2012, Ben-Ghiat 2005, Champagne 2013, Gori, 1999 and Wanrooij 2005).. The “new Italian man” was to be healthy, fit, disciplined (morally and physically), dominant, and aggressive. I suggest that the failure of these operas to present virile male protagonists partly stems from opera’s struggle to define and redefine itself in relationship to film.

Sound pictures, propaganda, and the rise of film in the 1930s

From the creation of the Istituto luce in 1924, the Fascist regime revealed a strong interest in the political potential of film10According to Gian Piero Brunetta, the Istituto luce was nationalized in 1925 for the dissemination of “propaganda and culture through cinematography” (“per la propaganda e la cultura per mezzo della cinematografia,” Brunetta 1991, p. 167).. Nevertheless, it was only in the 1930s that the regime fully exploited the power of film for the purpose of propaganda, an effort that culminated in the launch of Cinecittà in 1937. In the words of Italian film historian Gian Piero Brunetta, “the endeavors to turn cinema into a fascist art form were almost developed like the launch into orbit of a multi-stage rocket” (Brunetta 1991, p. 182)11“I tentativi di fascistizzazione del cinema si sviluppano quasi come la messa in orbita di un missile a più stadi.”, with stage two reaching its peak in 1932 at the opening of the Venice Film Festival. Marla Stone also identifies a “second phase” in the patronage practices of the Fascist state starting in the early thirties (1931–1936), when “the regime intervened to shape the content and social bases of cultural institutions through a policy of incentive, patronage, and experimentation” (Stone 1998, p. 7). Cinema found itself at the frontline of this shift in state involvement12In his article on the genre of the musical in Italy, Alex Marlow-Mann refers to “Fascism’s aims for a cinematic autarchy” (Marlow-Mann 2012, p. 83). James Hay also discusses the centrality of cinema, noting that “it is important, however, to recognize that the cinema was the culture industry at the center of Italy’s desire to assert and to defend through cultural policy […] Italian ideals of the day” (Hay 1987, p. 10).. The regime’s interest and involvement in the propagandistic potential of cinema increased in the early thirties, setting the medium apart from others. To Mussolini, film was “l’arma più forte” (“the strongest weapon”13This phrase, attributed to Mussolini, blazoned a banner during the launch of Cinecittà (reproduced in Brunetta 1991, p. 217). Of course, studies have repeatedly shown that reducing the films produced during the early thirties to overt propaganda can only prove simplistic (Brunetta 1991, Hay 1987, Landy [1986] 2014, Reich 2002, Ricci 2008). At the same time, a noted increase in state support towards the film industry and in the regime’s interest in cinema’s propagandistic potential does set film apart from other artistic genres.).

The first Italian sound pictures produced in the 1930s enhanced the privileged position of film, while thrusting the medium onto opera’s terrain. As Alex Marlow-Mann, Gianfranco Casadio, and Jeremy Tambling argue in their respective studies of the emergence of sound pictures, many of the first sound films revolved around opera: they portrayed opera singers, included opera arias, or, especially in Italy, represented the lives of operatic composers (Casadio 1995, p. 7, Marlow-Mann 2012, p. 81-82, Tambling 1987, p. 45-47). Although this could be interpreted as a sign of opera’s popularity and as an opportunity to expose opera to a larger public, it also implied that film could do what opera could, but with a wider impact.

Indeed, a perception of opera as elitist can be gleaned in some of the films produced in Italy during the early thirties. Operatic vocality does not appear to have a place in the “new order” apart from certain choral performances, such as in Carmine Gallone’s Scipione l’Africano (1937) or in Mario Camerini’s Il Signor Max (1937), where workers of the Opera nazionale del dopolavoro – a fascist workers’ association – perform Verdi’s “Va pensiero” (Nabucco, 1842), an operatic piece with a strongly politicized reception history, traditionally tied to the Risorgimento and to Verdi’s patriotism (Parker 1997, p. 20-41). In films produced in Italy during the early 1930s, choral singing predominates and popular and folk songs are represented as the ones that can unite all Italians. In Alessandro Blasetti’s Terra madre (1931), for example, the contrast between the corrupt city and the idyllic countryside takes on a musical form: the city folk play instrumental dance music such as jazz, fox-trot, and tango, whereas the peasants constantly sing folk songs together, as well as a choral “Ave Maria.” In Blasetti’s 1860 (1934), the events surrounding the Expedition of the Thousand are accompanied by popular songs of the Risorgimento, such as “La bella Gigogin” and “Addio mia bella addio”; singing “Fratelli d’Italia” unites Northern and Southern Italians before they leave for battle14Alberto Crespi discusses the use of popular songs in 1860 in his Storia d’Italia in 15 film (Crespi 2017).. Opera arias, on the other hand, seem to exist only in stuffy salons, to the fictional audience’s great dismay and boredom. In Camerini’s Ma non è una cosa seria (1936), a singer performs an ornate aria while the other characters yawn, show signs of impatience, or hold their head in their hands in exasperation (Video Excerpt 1).

Video excerpt 1: Mario Camerini, Ma non è una cosa seria (1936), operatic performance bores audience, 13:26-13:43 © Colombo Film / Ripley’s Home Video SRL [2003].

The operatic performance in Ma non è una cosa seria suggests that despite a wider circulation and democratization of opera during the nineteenth century, it remained an elitist art form. In his study of the dissemination of opera during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Robert Leydi concludes that despite a phantomatic presence of opera in the national consciousness, the opera-loving public was predominantly made up of the wealthy (Leydi 2003, p. 361). The movie audience, on the other hand, as James Hay’s research on popular film culture during the Fascist ventennio shows, was principally comprised of the middle and working classes (Hay 1987, p. 8). Studies of the popularity of film and opera both reveal a shift during the thirties: Leydi presents the thirties as a turning point after which the presence of opera recedes from everyday life (Leydi 2003, p. 289 and 366), whereas Brunetta calculates that in the years 1929–1930, the income from cinema constituted 61.9% of that of all cultural and sporting events, compared to 39.4% in 1924 (Brunetta 1991, p. 162). Whether through greater state involvement in cinematic production, the advent of sound pictures, or an increase in popularity, the 1930s presented a turning point in the prominence of film, which seems to have brought with it the decline of opera, forcing opera to measure itself against the new medium that was taking its place.

Cinematic and operatic masculinities

Film: virile condottieri and weak lovers

Existing scholarship on male protagonists in Italian films from the 1930s distinguishes the protagonists of historical films who embody the fascist ideals of virility from those of sentimental comedies and melodramas who are portrayed as weak and effeminate but reform into the “new Italian man” at the end of the movie (Cottino-Jones 2010, Dalle Vacche 1991, Gundle 2013, Landy [1986] 2014 and 1998). I would like to propose a new categorization of male protagonists in these films that allows for a better understanding of their treatment in different cinematic genres and facilitates a comparison with opera. Rather than separating male protagonists into two categories (virile protagonists in historical films and effeminate protagonists in all other genres), I suggest dividing them into three categories, based on the following distinguishing criteria: whether or not the protagonist is a political leader (condottiero), whether or not he evades his duty, and whether or not he falls in love15The last two criteria tend to go hand in hand: during this period, protagonists in the role of lovers generally evade their duty and systematically reform at the end of the film through the love of a virtuous woman.. Distinguishing political leaders from other male protagonists allows one to differentiate the portrayal of male protagonists in historical film, drama, and comedy, as well as to reflect on the unique treatment of these characters due to their inevitable comparison with Mussolini.

With these distinctions in mind, I propose a typology of male protagonists who appear in Italian films from the beginning to mid-1930s:

- Political leaders in historical films who do not get involved in love intrigues and do not evade their duty, but rather heroically lead their people to victory.

- Political leaders who forget their duties after having been led astray by their love for the wrong woman, but then reform through the love of a virtuous woman who embodies the fascist ideals of femininity (appearing in dramas).

- Lovers who are not political leaders and who shirk their manly duties out of idleness or immaturity, but then reform through the love of a virtuous woman who embodies the fascist ideals of femininity (appearing in comedies).

The distinction between the weak lovers of comedies and the political leaders of dramas, both renegades in need of reform, also operates at the level of public and private spheres: the virility of political leaders exists through the adoring eyes of others in public spaces, whereas the reform of the everyday hero of comedies into a “new man” happens in the domestic sphere, with his new wife as witness.

As Stephen Gundle, Margo Cottino-Jones, and Marcia Landy have shown, Vittorio De Sica’s roles in Gli uomini che mascalzoni (1932), Darò un milione (1935), Ma non è una cosa seria (1936), and Il Signor Max (1937), by Mario Camerini best exemplify the effeminate portrayal of weak renegade lovers in Italian comedies of the time (Cottino-Jones 2010, Gundle 2013, Landy [1986] 2014). This effeminate characterization reaches its extreme in Darò un milione, where De Sica’s character Gold wears Anna’s robe when trying to seduce her. De Sica’s characters also turn towards singing and dancing when seducing women, techniques more often associated with feminine charm. Intriguingly, the women in these films do not sing. In Gli uomini che mascalzoni, for example, De Sica’s character sings “Mariù” to Mariuccia, winning her over. De Sica’s enchantment of women through song may tie these comedies to opera. Unlike their operatic counterparts, however, the protagonists of these films reform their ways in the end, understanding the importance of hard work and of domestic bliss with a faithful wife and thus aligning themselves with the fascist ideals of the “new Italian man.” In contrast to films about political leaders, this reform happens in the private sphere, and is generally witnessed by the new wife and a benevolent father figure, symbolizing the reformed man’s acceptance by patriarchal society.

Traditionally, critics oppose the effeminate protagonists of comedies to the virile heroes of historical films, the embodiments of the archetypal fascist male. Separating political leaders from other male protagonists adds another layer to this contrast. In historical films, the political leader does not take part in love narratives and his virility is expressed through public acclaim and military prowess. In 1860, Garibaldi appears as a presence that can inspire others to action. He is rarely shown on-screen and, when he is, it is at a distance. At the crucial moment, his words rouse the discouraged troops into the final battle (Video excerpt 2)16Landy describes Garibaldi in 1860 as “a mythic protagonist, but he is remote, visible only in a few long shots” (Landy 1996, p. 119).. However, instead of filming Garibaldi, Blasetti focuses on the awestruck eyes of his troops: it appears Garibaldi’s virility can best be expressed in his impact on others. In Gallone’s Scipione l’Africano (1937), many scenes show us the adoring eyes of the masses, inspired to action by their hero Scipione. The hero is also presented as an excellent orator, and his control of the people who express their devotion to him through choral song contributes to the projection of his strength. Both Garibaldi and Scipione present a public virility that allows the condottieri to lead their people to victory. Though we do see Scipione in a domestic scene with wife and child, the power of both heroes in the public sphere sublimates their activities in the private sphere. Such public virility and sublimation of the private sphere distinguishes historical film from opera, despite similarities in setting.

Video excerpt 2: Alessandro Blasetti, 1860 (1933), Garibaldi’s voice rouses soldiers to battle, 01:10:25-01:10:53 © Cines Pittaluga SA / Ripley’s Home video SRL [2007].

The renegade political leaders of dramas are not discussed separately from the other two character types in the literature; yet, their treatment differs significantly from both the virile political leaders of historical films and the effete lovers of comedies. Although they evade their duties, they cannot be presented as weak in the same way as the protagonists of comedies because of their possible comparison with Mussolini in their role of condottieri. In Terra madre (Blasetti 1931), the protagonist – a landowner distracted by city-life – has forgotten his duties to the peasants who work for him. Though corrupted by city values (and city women), he has not lost his virility: he wrestles a bull and holds him by the horns with his bare hands in front of a cheering crowd and he later runs into a burning house to save a child. Though he needs to be reminded of his duties as a leader (by a virtuous woman), his masculinity remains intact and, as in the case of Scipione and Garibaldi, the camera often films the adoring gaze of the people upon him. The hero’s virility is, once again, expressed and validated through public adoration.

In Resurrectio (Blasetti 1931), the love of a femme fatale compromises the virility of the protagonist (this time a conductor, another condottiere figure): he decides to kill himself, and the shots of him with his very small gun leave little doubt as to his emasculation (Video excerpt 3). A virtuous (and very enterprising) young woman saves him and slowly pulls him out of his apathy. At the end of the movie, the protagonist’s virility returns, once again in a very public manner. He first enthrals the audience with his conducting skills, and then, when a storm interrupts the concert and sends the public into a panicked frenzy, he calms them by gloriously playing a giant organ (filmed from the bottom up, a clear phallic symbol). Once again, the camera films the awestruck eyes of the audience, showing the conductor’s virility in his effect on others (Video excerpt 4). “You controlled a crowd,” the femme fatale tells him, impressed, attempting to rekindle their flame17“Hai controllato una folla.”. Unfortunately for her, the conductor has reformed and can now resist the temptress thanks to his love for the virtuous young woman (referred to only as “the girl” – “la fanciulla”).

Video excerpt 3: Alessandro Blasetti, Resurrectio (1931), the hero’s very small gun, 07:02-07:23 © Cines Pittaluga SA / Ripley’s Home video SRL [2003].

Video excerpt 4: Alessandro Blasetti, Resurrectio (1931), the hero saves a crowd by playing the organ, 49:41-51:42 © Cines Pittaluga SA / Ripley’s Home video SRL [2003].

Despite their need for a woman to remind them of their duties, the virility of political leaders must be expressed through public adoration, setting them apart from the male protagonists of comedies. At the same time, their momentary weakness, often characterized by their attraction to the wrong woman (a femme fatale in Resurrectio, a promiscuous city woman in Terra madre), distinguishes them from the heroes of historical films, and shows the possibility of vulnerability in the private sphere, even for public heroes. Considering that the protagonists of opera tend to be political leaders who reveal their private lives, one could expect them to be portrayed similarly to the renegade political leaders of dramas. This is, however, not the case: in opera, male protagonists are overwhelmingly presented as lacking virility, and they do not reform.

Opera and the uomo non-vir

Similarly to films presenting political leaders as protagonists, the operas composed during the early-to-mid thirties can be divided into two main categories: those in which a romantic intrigue plays a central role, and those in which it does not. The operas whose plot does not revolve around romance tend to focus on past political intrigues, tying the works to the filmic genre of historical films rather than to the operatic tradition. Indeed, whereas some of Verdi’s operas contain political intrigues, they never omit the often-destructive love between soprano and tenor18Verdi’s revised version of Simon Boccanegra, in which Boccanegra looms over the other characters, might be read as a previous example in which politics overshadow the love intrigue, without, however, erasing it.. Puccini’s operas also tend to revolve around tragic love. By de-emphasizing love intrigues, these operas distinguish themselves from their predecessors, rendering their portrayal of historical political figures more significant in light of the inevitable parallel between fictional political leaders and Mussolini19In her rich analysis of Il deserto tentato (Alfredo Casella, 1937), Laura Basini argues for a parallel between the “primo aviatore” and Mussolini (Basini 2012). Nevertheless, in the work’s list of characters the “Aviatori” are presented as a single entity and they often sing together, reducing the importance of the “primo aviatore” as protagonist.. The operas that do revolve around love intrigues also differ from operatic conventions. Indeed, most protagonists in operas by Verdi and Puccini are portrayed as virile20Mario Cavaradossi (Tosca 1900), who bravely resists torture to protect a friend and his political beliefs, and Prince Calaf, who does not fear death and seduces Turandot (Turandot 1926), are examples of Puccinian virile male protagonists. Some Verdian leading tenor roles have been read as anti-heroes and as expressing a social critique (Gerhard 1998, pp. 100-105, de Van 1998, pp. 107-108 and 190-193, among others). However, their failings seem to be more linked to an excess of virility (such as Alfredo’s jealousy and blindness in La Traviata 1853) than to the physical weakness and indolence found in the protagonists of the operas composed in Italy during the 1930s.. When they are not, they often play opposite a strong male protagonist, typically a baritone or bass, presented as a foil for the young tenor-hero21This is most common in Orientalist operas, which, as Ralph Locke describes, tend to contain a “brutal, intransigent tribal chieftain (bass or bass-baritone),” presented as virile and creating further tension for the “young tenor-hero” (Locke 1991, p. 163). A clear example of this can be found in Carmen, where, as Steven Huebner argues, Escamillo and José are portrayed in binary opposition, the former’s virility highlighting the latter’s weakness: “Carmen is […] centrally about male madness, and the transformation of José into an animal – in stark contrast to Escamillo, the other leading male and a ‘true-life’ matador” (Huebner 1993, p. 4). Locke discusses this … Continue reading. In Italian operas composed during the early-to-mid thirties by contrast, male protagonists (be they tenors or baritones) tend to be political leaders (or their youthful successors), are systematically presented as weak, effeminate, or unfit, and they remain so throughout the opera, instead of reforming as they do in film. These protagonists can be divided into two categories:

- political leaders who avoid their duties out of cowardice and indolence

- political leaders who are presented as weak and unfit because of old age, health issues, or their consuming desire for a woman.

The first type of political leader appears in operas that do not revolve around a romantic intrigue. In Pietro Mascagni’s Nerone (1935, libretto by Giovanni Targioni-Tozzetti), the title character shirks his duty as a ruler by singing and drinking instead of protecting his people from foreign invasion, and appears as a coward throughout the opera22When discussing the impending attack on Rome by Gauls and Britons, Atte tells Nerone “And what do you do, Nerone? What steps do you take towards your impending ruin? You drink! You sing and drink…” (“E tu, Nerone, che fai? Come provvedi alla ruina che ti sovrasta? Bevi! Canti e bevi…”) (Mascagni 1934, p. 43). Furthermore, Nerone’s cowardice is mentioned nine times in the opera (Mascagni 1934, p. 12, 46, 47, 65, 159, 164, 187, 199, and 207).. “Il Principe” (“The Prince”) – one of two male protagonists in Gian Francesco Malipiero’s La favola del figlio cambiato (1934, libretto by Luigi Pirandello) – refuses to return home to become king after his father’s death, sending the village idiot (called “Figlio di re,” “King’s son”) in his place. He justifies his decision to his ministers by describing his fear of death: “I have already risked death … don’t you think that is enough?23“Ho rischiato, signori Ministri, di morire anche qua. Non vi pare che possa bastare?” (Malipiero 1953, p. 201-202).”.

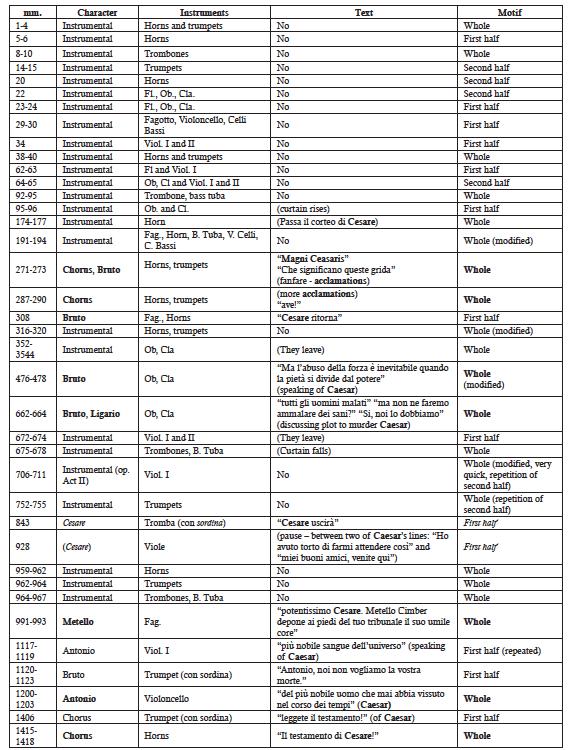

Besides evading their duty, both characters appear weak or effeminate, especially in contrast with other men. Nerone’s first appearance onstage shows him losing a fight to an old man, and he later characterizes himself as an artist, an occupation that was considered as low in virility by fascist standards24According to Sandro Bellassai, intellectuals and artists were considered by the Fascist regime as lacking in virility. He writes “intellectualism was a pathology of masculinity [;] it was precisely an ‘intelligence without virility’” (Bellassai 2005, p. 321).. In La favola, the first words pronounced by “The Prince” compare his passivity to that of a “lady, laying down, half-naked25His ministers tell him “Your Majesty! You should understand…Yes, understand…understand that this indolence…” to which he responds “…of a lady laying down, half naked…” (“Ecco, già, Maestà, Maestà! Dovrebbe capire…Ecco, capire…capire che questa indolenza…” “…di dama sdrajata seminuda…”) (Malipiero 1953, p. 128).”. Malipiero’s musical setting further expresses the lack of virility of “The Prince” through musical topic and rhythm: a low-register, martial-like (and thus more masculine) accompaniment for “The Ministers” (baritones) alternates with a higher-register, fluid, and chromatic accompaniment for “The Prince” (a tenor) throughout the scene (Examples 1 and 2, and Figure 126As you can see, the Ministri are always accompanied by a low register (bass clef only), whereas the Principe is generally accompanied by a higher register (indicated as bass and treble in the table and shown in bold). The only exceptions (italicized in the table) to the Principe’s accompaniment are when he talks of his duty: he then takes on the same low register as his ministers).). The only times when the accompaniment transfers to a lower register for “The Prince” as well are those in which he speaks of his duty.

![Example 1: Gian Francesco Malipiero, <em>La favola del figlio cambiato</em> (1933), opening of the fourth quadro, low register and martial rhythms associated with the Prince’s ministers, mes. 1-6, p. 127 © Casa Ricordi [1953].](https://revuemusicaleoicrm.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/virilecondottierion-screenandemasculatedheroesontheoperaticstage_5-1024x785.jpg)

Example 1: Gian Francesco Malipiero, La favola del figlio cambiato (1933), opening of the fourth quadro, low register and martial rhythms associated with the Prince’s ministers, mes. 1-6, p. 127 © Casa Ricordi [1953].

![Example 2: Gian Francesco Malipiero, <em>La favola del figlio cambiato</em> (1933), change of register and texture for the Prince’s entrance, mes. 9-13, p. 128 © Casa Ricordi [1953].](https://revuemusicaleoicrm.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/virilecondottierion-screenandemasculatedheroesontheoperaticstage_6-1024x484.jpg)

Example 2: Gian Francesco Malipiero, La favola del figlio cambiato (1933), change of register and texture for the Prince’s entrance, mes. 9-13, p. 128 © Casa Ricordi [1953].

![Figure 1: Register alternation in the accompaniment of prince and his ministers in the fourth quadro of Gian Francesco Malipiero, <em>La favola del figlio cambiato</em> (1933) © Casa Ricordi [1953].](https://revuemusicaleoicrm.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/virilecondottierion-screenandemasculatedheroesontheoperaticstage_tableau1.jpg)

Figure 1: Register alternation in the accompaniment of prince and his ministers in the fourth quadro of Gian Francesco Malipiero, La favola del figlio cambiato (1933) © Casa Ricordi [1953].

Could these protagonists be interpreted as counter-examples, as embodiments of values excoriated by the Fascist regime? Portraying Nerone as a virile hero would indeed have been problematic (given that he was considered a ruthless tyrant), and his weakness could be interpreted as justifying his death and the rebellion of his people against him27Indeed, Maria Wyke notes that “the Neronian narrative was a wholly inappropriate paradigm for aspirations of the Fascist regime” (Wyke 1997, p. 129).. Furthermore, “The Prince,” described as foreign, “perhaps English,” “sick,” “pale as wax, with blond hair,” sent to the Riviera to heal, and revealing a delight for nature and preoccupation with fashion, could be interpreted as a critique of the bourgeoisie28“L’ho visto io. Com’era? Malato. Ah sì? Malato? Un visino di cera…capelli biondi…Inglese? Non so di che paese. L’hanno mandato alla nostra riviera…” (Malipiero 1953, p. 94-95). Bellassai, describes the fascist view of the bourgeois as characterized by a “veritable deficit of masculinity” (Bellassai 2005, p. 324).. Nevertheless, these operas do not present an alternative model of masculinity embodied by a protagonist who can bring a new political order and vanquish weak idle cowards29In his study of fascist theatre, Pietro Cavallo notes that one of the most widespread plot-types in spoken theatre was that of the opposition between two protagonists, a fascist and a socialist or a fascist and a bourgeois, in which the non-fascist character (associated with darkness and sickness) ends up “converting” to fascism (associated with light and strength) (1990, pp. 47-87). The description of the two boys at the beginning of the opera seems to set up this opposition between two characters, the first associated with light and strength (fascist) and the other with darkness and sickness (non-fascist): “Like a sun, he was healthy and plump, full of life; and the other instead, … Continue reading. In Nerone, the female characters appear stronger than the men. Indeed, Atte and Egloge are the only characters of the opera who do not fear Nerone. In La favola del figlio cambiato, “The King’s Son,” who is mocked by all and expresses himself as a child might, using “g”s instead of “r”s (“pottaghmi co quetta coghona e quetta gheghina a mmio ghegno, sedeghe su xxrhono”) for example, takes the place of “The Prince” as ruler30“pottaghmi co quetta coghona e quetta gheghina a mmio ghegno, sedeghe su xxrhono” should read “portarmi con questa corona e questa regina a mio regno, sedere su trono,” a phrase that also presents an error in syntax (Malipiero 1953, p. 105-106).. Although most operas composed during the early-and-mid thirties portray rulers who neglect their duty for a number of reasons (old age, sickness, love), the cowardly political leaders in Nerone and La favola del figlio cambiato appear to have been too much for the time. Significantly, these are the only two operas that met with a hostile reception and problems with censorship31Based on the revisions Malipiero made to the opera following its cancellation, Fiamma Nicolodi has suggested that Mussolini took offense to the opera because the second quadro took place in a brothel (1984, pp. 221-229). On the scandal caused by La favola, see (Frese Witt 1993 and Waterhouse 1999, pp. 181-190). Pestalozza read the cancellation of the opera in support of his theory of Malipiero’s antifascist leanings (2004). For critical responses to Nerone, see (Mallach 2002, p. 269-288 and Nicolodi 2004)..

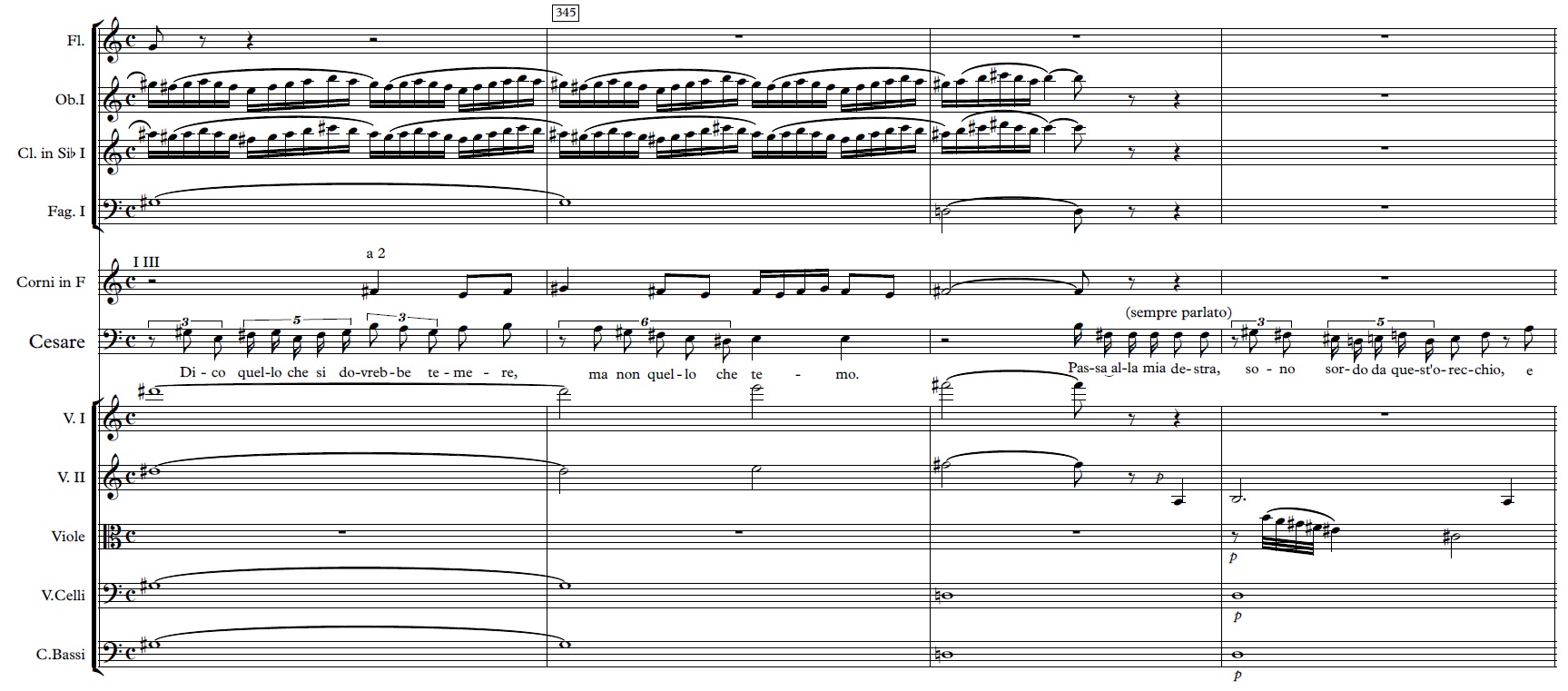

Though Nerone and La favola present extreme cases of unfit rulers, all the operas composed in Italy during this period portray weak political leaders onstage. Some are weak due to ill health or old age, as in the case of Marco Orsèolo, “Inquisitor of the State and head of the Council of Ten” (“Inquisitore di Stato e capo dei Dieci”) in Ildebrando Pizzetti’s Orsèolo, and, perhaps more significantly, of Caesar himself in Malipiero’s opera Giulio Cesare (1935), dedicated to Mussolini. Based on Shakespeare’s portrayal of Caesar in Julius Caesar, Malipiero’s Cesare is deaf in one ear and has an epileptic seizure, which another character vividly describes. Malipiero could have easily cut these lines. Instead, he brings them out with a sparse accompaniment texture that facilitates the understanding of the words (Examples 3 and 4 and Audio excerpts 1 and 2). This portrayal of Caesar goes against fascist discourse on the Roman hero, as Caesar was often compared to Mussolini: in his biography of Caesar, the journalist Umberto Silvagni refuted the notion that Caesar was epileptic, stating that his qualities were those of the “healthy and vigorous” (Silvagni 1930, p. 352)32“sano e vigoroso.” Silvagni compares Caesar to Mussolini later in the biography (Silvagni 1930, p. 326-327).. Malipiero’s portrayal of Caesar leaves us once again searching for an example of male virility on the operatic stage33Much has been written on Mussolini’s appropriation of the figure of Caesar and on the complex reception of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar during the Fascist regime. Maria Wyke explains this complexity: “Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar was dangerous in its apparent depiction of […] the possibility of subversion and the mortality of a dictator,” but, in order to avoid such dangers, “ambiguities could be elided, Caesar exalted, Brutus denigrated, and Antony allocated no sinister intent” (Wyke 1999, p. 173). On the portrayal of Caesar in fascist theatre, see Dunnett 2006 and Nelis 2007..

Example 3: Gian Francesco Malipiero, Giulio Cesare (1936), sparse accompaniment texture when Caesar mentions his deafness (m. 346-347), m. 344-347, p. 32 © Casa Ricordi.

Audio excerpt 1: Gian Francesco Malipiero, Giulio Cesare (1956), Caesar’s deafness, CD 1, track 5, 01:34-01:50, recorded performance by the RAI Symphony Orchestra and Chorus conducted by Nino Sanzogno © Great Opera Performances [2006].

Example 4: Gian Francesco Malipiero, Giulio Cesare (1936), sparse accompaniment texture when Casca describes Caesar’s epileptic seizure, m. 410-413, p. 38 © Casa Ricordi.

Audio excerpt 2: Gian Francesco Malipiero, Giulio Cesare (1956), Caesar’s epileptic seizure, CD 1, track 6, 03:14-03:35, recorded performance by the RAI Symphony Orchestra and Chorus conducted by Nino Sanzogno © Great Opera Performances [2006].

The consuming desire for a woman (often a femme fatale) also instigates operatic political leaders to stray from their duty, a weakness they share with the protagonists of dramas. In Lucrezia (1937), Ottorino Respighi and librettist Claudio Guastalla push the effeminacy caused by the inappropriate desire for a woman to the extreme: a female voice speaks for Tarquinio, the “son of a king,” to express his desire for Lucrezia. The opera contains a narrator figure, “La Voce,” sung by a mezzo-soprano. Though she generally refers to the characters in the third person, on two occasions this female voice switches to the first person: in both cases she speaks for Tarquinio34“I, that am the son of a king” (“Io, che son figlio di re”) (Respighi 1936, p. 33); “in an hour…I will have you, wondrous prey that are worth a kingdom!” (“Fra un’ora…Io ti tengo, superba preda che vale un regno!”) (Respighi 1936, p. 53)..

In La fiamma (1934) by Ottorino Respighi and librettist Claudio Guastalla and Antonio e Cleopatra (1937) by Gian Francesco Malipiero, an Oriental temptress – the Byzantine witch Silvana in La fiamma and the Egyptian queen Cleopatra in Antonio e Cleopatra – seduces and dominates a political leader, leading him to neglect his duties. Both libretti, based on plays – The Witch (1908) by Hans Wiers-Jenssen and Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra (1606?) – change the plot in order to emphasize the woman’s power and the man’s submission. Whereas Shakespeare’s play stages the political conflict between Antony, Octavius Caesar, and Pompey, who all three aspire to control Rome, Malipiero excludes this conflict from the plot. Without a political justification for his actions, Antony appears as an idle man who has forgotten his mission and love of war, thus losing his virility. This lack of virility also appears in his vocal lines, which gradually include what John Waterhouse calls the “overtly ‘exotic’ augmented seconds” associated with Cleopatra (Waterhouse 1999, p. 198).

In La fiamma, the Oriental temptress Silvana controls two men: her husband Basilio, exarch of Ravenna, and his son, Donello. Whereas the domination of a weak tenor by an exotic femme fatale can be tied to the tradition of Orientalist nineteenth-century operas, her subjugation of the baritone – in this case, the political leader – breaks with both the tradition of Orientalist operas and the cinematic portrayal of political leaders. Basilio’s weakness also moves away from the opera’s source-play. In the play, Absolon (Basilio) loves Anne (Silvana) of his own free will, whereas Silvana’s mother bewitches him into love in Claudio Guastalla’s libretto. Respighi also represents Basilio’s weakness musically. The exarch’s first appearance, accompanied by brass instruments playing held accentuated chords in a slow tempo, presents him with all the majesty and virility of his office. This passage is followed by a section in which the orchestra plays a motif associated with horseback riding (Examples 5 and 6 and Audio excerpts 3 and 4). When Basilio describes the way Silvana’s mother mesmerized him, his musical style changes completely, becoming melismatic, a characteristic of Silvana’s own vocal lines in the opera (Examples 7 and 8 and Audio excerpts 5 and 6). Basilio’s integration of Silvana’s melismatic style, leading to the breakdown of his virile horseback-riding motif, characterizes him as a weak man, dominated by Silvana and her mother.

![Example 5: Ottorino Respighi, <em>La fiamma</em> (1933), Basilio’s entrance, no 87, mes. 1-6, p. 142 © Casa Ricordi [2000].](https://revuemusicaleoicrm.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/virilecondottierion-screenandemasculatedheroesontheoperaticstage_12-1024x881.jpg)

Example 5: Ottorino Respighi, La fiamma (1933), Basilio’s entrance, no 87, mes. 1-6, p. 142 © Casa Ricordi [2000].

Audio excerpt 3: Ottorino Respighi, La fiamma (1955), Basilio’s entrance, CD 1, track 10, 00:00-00:21, recorded performance by the RAI Symphony Orchestra and Chorus conducted by Francesco Molinari-Pradelli © Allegro Corporation / Opera d’Oro [2006].

![Example 6: Ottorino Respighi, <em>La fiamma</em> (1933), horseback-riding motif, no 88, mes. 1-6, p. 143 © Casa Ricordi [2000].](https://revuemusicaleoicrm.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/virilecondottierion-screenandemasculatedheroesontheoperaticstage_14-1024x668.jpg)

Example 6: Ottorino Respighi, La fiamma (1933), horseback-riding motif, no 88, mes. 1-6, p. 143 © Casa Ricordi [2000].

Audio excerpt 4: Ottorino Respighi, La fiamma (1955), horseback-riding motif, CD 1, track 10, 00:51-01:09, recorded performance by the RAI Symphony Orchestra and Chorus conducted by Francesco Molinari-Pradelli © Allegro Corporation / Opera d’Oro [2006].

![Example 7: Ottorino Respighi, <em>La fiamma</em> (1933), Silvana’s melismatic vocal lines, no 16, mes. 8-11, p. 25 © Casa Ricordi [2000].](https://revuemusicaleoicrm.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/virilecondottierion-screenandemasculatedheroesontheoperaticstage_16-1024x856.jpg)

Example 7: Ottorino Respighi, La fiamma (1933), Silvana’s melismatic vocal lines, no 16, mes. 8-11, p. 25 © Casa Ricordi [2000].

Audio excerpt 5: Ottorino Respighi, La fiamma (1955), Silvana’s melismatic vocal lines, CD 1, track 03, 01:21-01:39, recorded performance by the RAI Symphony Orchestra and Chorus conducted by Francesco Molinari-Pradelli © Allegro Corporation / Opera d’Oro [2006].

![Example 8: Ottorino Respighi, <em>La fiamma</em> (1933), Basilio’s style becomes melismatic when he refers to Silvana’s mother, no 96, mes. 6-13, p. 157 © Casa Ricordi [2000].](https://revuemusicaleoicrm.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/virilecondottierion-screenandemasculatedheroesontheoperaticstage_18-1024x761.jpg)

Example 8: Ottorino Respighi, La fiamma (1933), Basilio’s style becomes melismatic when he refers to Silvana’s mother, no 96, mes. 6-13, p. 157 © Casa Ricordi [2000].

Audio excerpt 6: Ottorino Respighi, La fiamma (1955), Basilio’s style becomes melismatic when he refers to Silvana’s mother, CD 1, track 12, 00:04-00:22, recorded performance by the RAI Symphony Orchestra and Chorus conducted by Francesco Molinari-Pradelli © Allegro Corporation / Opera d’Oro [2006].

At a time when virile political leaders dominated the silver screen, the leaders in Italian operas systematically appeared weak and unfit to rule. This is surprising at a time that saw a greater control over the arts by the Fascist regime and Mussolini’s growing imperial ambitions. Could these weak rulers represent an old order, in need of replacement by a new (fascist) one? In this light, these operas could be read as justifying the Fascist regime. This might explain why the only operas for whom the ruler’s lack of virility hindered the work’s reception are Nerone and La favola del figlio cambiato. In both operas, cowardice constituted the protagonists’ sole excuse for neglecting their duties, with no other model of masculinity available, no new order apparent. If the operas produced during the 1930s were indeed meant to justify the regime, they would have needed to offer virile replacements for their unfit political leaders. Many of the operas composed during the period present younger male protagonists in line to replace the older and unfit rulers; nevertheless, their virility remains problematic or ambiguous at best.

The musical virility of young successors

In La fiamma, Basilio’s son Donello is the only other male protagonist. He cannot be interpreted as a virile successor because Silvana dominates him too: she seduces him and her melismatic vocal style enters his lines just as it did his father’s. Though Donello repudiates Silvana at the end of the opera, Basilio’s mother Eudossia is the one who stands up to her and instigates her punishment. Donello’s actions and musical lines are always dictated by women, first by Silvana, then Eudossia. In Lucrezia (1937), Giunio Bruto appears to be the evil Tarquinio’s replacement and successor, with the final chorus (quoted at the beginning of this article) containing cries of “You be Duce, Bruto!” (Respighi 1936, p. 117). Nevertheless, in the first part of the opera Bruto is the laughing stock of the other male characters: they refer to him as “oh so foolish,” tell him that he “does not count,” and say “when you want to laugh, look at Giunio [Bruto]” (ibid., p. 9-26)35“stoltissimo Bruto,” “Brutissimo, tieni, tu che non conti…” “E quando vuoi ridere, guarda Giunio…”.

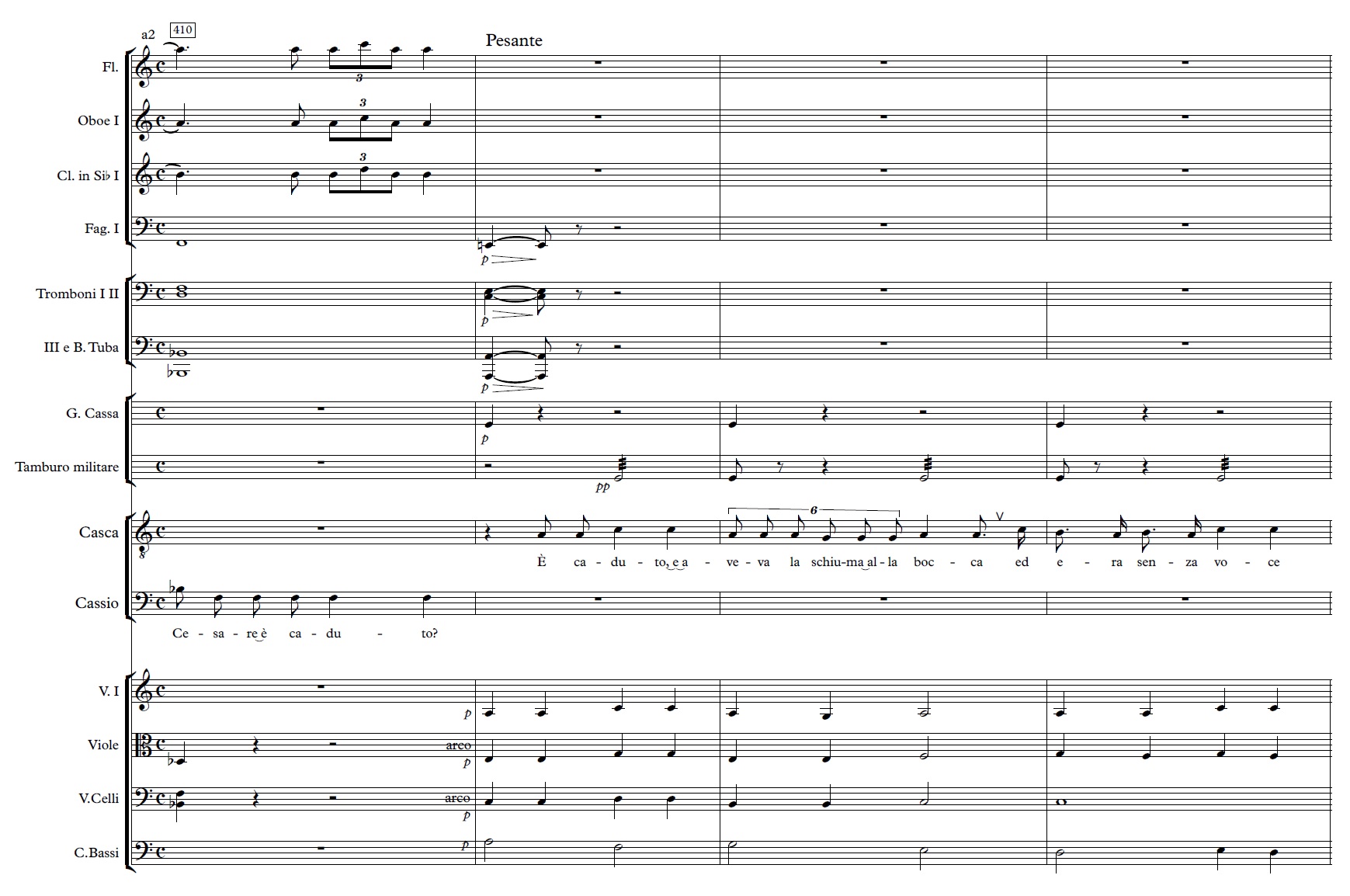

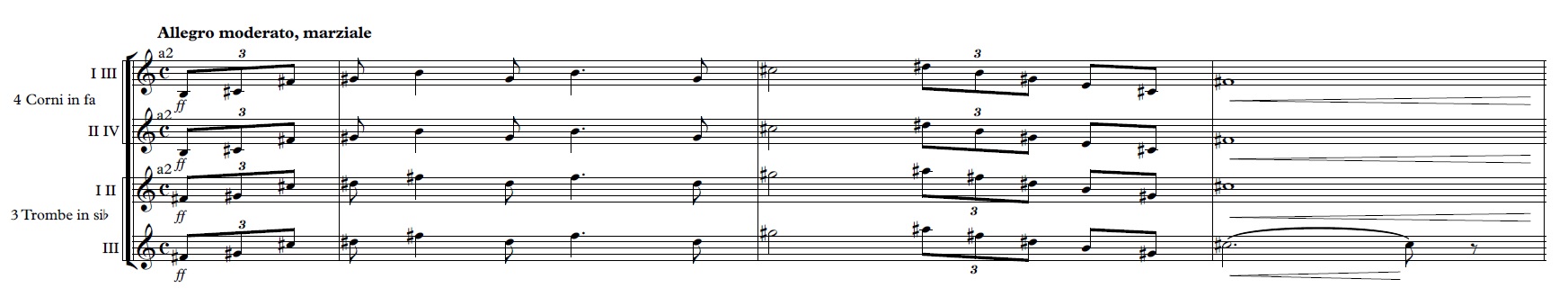

Malipiero composed Antonio e Cleopatra shortly before the important celebrations of the bi-millennium of Augustus in 1937–1938 (planned since the early 1930s), making the character of Ottaviano (the future Caesar Augustus) the ideal choice for an example of Roman virility in contrast with Antonio. Curiously, Malipiero mutes Ottaviano throughout the opera. Others speak for him or to him, and he sings only four lines. For his first appearance, in Act II, the stage directions indicate that Antonio is answering Ottaviano, though we do not hear Ottaviano’s question, and his first sung intervention is “in a low voice to Antonio” (Malipiero 1937, p. 106-107)36“sottovoce ad Antonio.”. In the final act of the opera, two messengers speak for him, but he does not sing again. In 1860, Garibaldi rarely speaks and appears on-screen very little, often at a distance. Nevertheless, his words are the ones that rouse his people to battle, and his virility emerges in the adoring eyes of his followers. Malipiero’s muting of Ottaviano may well be a similar attempt to represent him at a reverential distance. In the opera’s final scene, trumpet blasts in a martial-like rhythm accompany Ottaviano’s arrival (Example 9). This conventional expression of virility could replace the shots of the adoring eyes of the people. In the musical postlude following Cleopatra’s death, this martial motif sounds once again but Cleopatra’s augmented second follows it abruptly, ending the opera and giving the Egyptian queen the final word: musically, she wins over Ottaviano, rendering even his musical expression of virility ambiguous and ineffective (Example 10).

Example 9: Gian Francesco Malipiero, Antonio e Cleopatra (1938), Ottaviano’s entrance, mes. 2120-2123, p. 211 © Sugarmusic S.p.A. / Edizioni Suvini Zerboni.

Example 10: Gian Francesco Malipiero, Antonio e Cleopatra (1938), end of the opera, Cleopatra has the last word, mes. 2177-2183, p. 217 © Sugarmusic S.p.A. / Edizioni Suvini Zerboni.

Orsèolo presents another example of a muted young successor. In the opera, the political leader is Marco Orsèolo, “Inquisitor of the State and head of the Council of Ten.” His son Marino, accused of kidnapping Rinieri’s sister, flees the city, dishonouring his family name. At the end of the opera, we discover that he enrolled in the army under a false name and died while protecting his country. Marino only sings at the beginning of the opera, but in the final act he overshadows the other male protagonists: a processional chorus sings “il gran Te Deum” in his honor for most of the scene, breaking into cries of “Gloria a Marino Orsèolo!” Having died while protecting his country, Marino regains the manhood he had lost by kidnapping a young woman and then fleeing. These expressions of public and choral adoration are reminiscent of those in contemporary film. But in opera it appears as though male characters can only be shown as virile in death or in absentia.

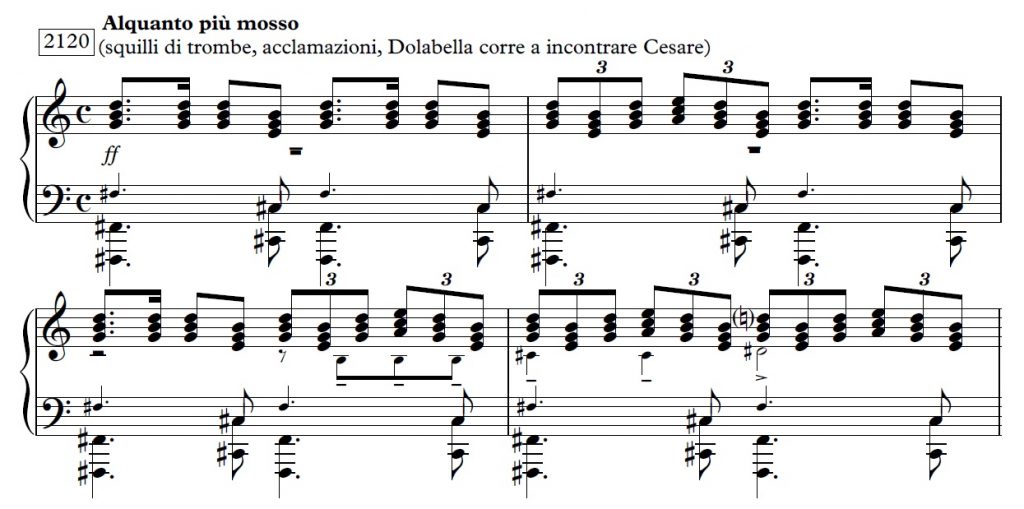

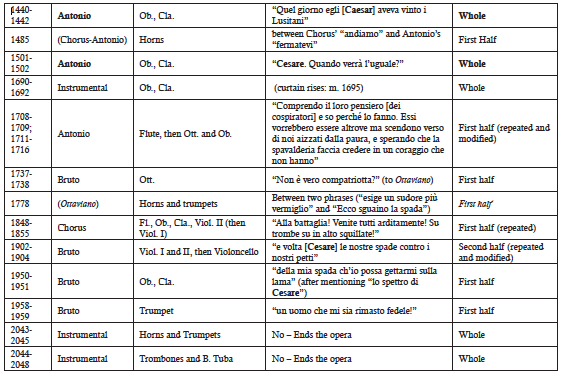

In Giulio Cesare, Caesar dominates the opera musically, overshadowing the other male protagonists despite his old age and frail health. A heroic motif associated with Caesar opens the opera and sounds when he is about to come onstage and when other characters talk about him (Example 11 and Audio excerpt 7). Surprisingly, the full motif never accompanies Caesar. Though his successor Ottaviano (Augustus) appears at the end of the opera, the heroic motif continues to refer to Caesar rather than to him, casting ambiguity on the virility and legitimacy of Caesar’s successor (Figure 2). Furthermore, as shown in Figure 2, once Ottaviano appears, the full motif is not played again until the end of the opera. As in the case of Ottaviano in Antonio e Cleopatra, this musical expression of conventional manhood could be interpreted as an operatic expression of public virility. In Giulio Cesare the motif appears to be associated with Caesar’s spirit, or with Caesar the public figure, but not with Caesar the man. Whereas the private dimension of political leaders does not stop them from public expressions of virility in dramas, in opera, the private dimension of the protagonists seems to preclude virility: public virility, instrumental or choral, can only be expressed in the protagonist’s absence.

Example 11: Gian Francesco Malipiero, Giulio Cesare (1936), heroic motif associated with Caesar, mes. 1-3, p. 1 © Casa Ricordi.

Audio excerpt 7: Gian Francesco Malipiero, Giulio Cesare (1956), Caesar’s heroic motif, CD 1, Track 1, 00:00-00:05, recorded performance by the RAI Symphony Orchestra and Chorus conducted by Francesco Molinari-Pradelli © Great Opera Performances [2006].

Figure 2: Appearances of Caesar’s heroic motif in Gian Francesco Malipiero, Giulio Cesare (1936) © Casa Ricordi.

The emasculation of opera’s male protagonists: a response to the rise of film?

My analysis of the portrayal of male protagonists in operas composed during the 1930s suggests that whether they represent political leaders or their youthful successors none embodies the fascist ideal of virility. Because this portrayal differs both from contemporary film and from operatic tradition more generally, a question remains: why? Viewing this tendency as a subversive gesture against the regime would be difficult to sustain because it would not be possible to pin anti-fascist leanings on all the opera composers of the period, as Fiamma Nicolodi’s rich archival research has shown (1984). Rather, this section will explore how this curious treatment of male protagonists may be a response to the contemporary rise of film. As I have argued, the 1930s saw a fundamental shift in the balance of power between opera and cinema: film was privileged by the Fascist regime, saw a strong increase in popularity, and with the advent of sound pictures could do everything opera could. I suggest that this transition forced opera to redefine itself in relation to film.

Indeed, opera found itself sitting uncomfortably between operatic traditions and new generic distinctions brought on by cinema: its staging of historical figures tied it to historical films, but its conventional plots, focusing on love stories, linked it to dramas and light sentimental comedies37Scholarly literature on films of the early thirties tends to focus more on film directors – especially Alessandro Blasetti and Mario Camerini – (Brunetta 1991, p. 191-203; Celli and Cottino-Jones 2007, p. 19-38) or actors (Gundle 2013 and Landy 2008) than on generic distinctions, though some authors create their own distinctions (Hay 1987) or discuss ways in which the films of the period circumvent them (Landy 2000). The only genres that appear clearly defined are those of the historical film and of comedy, though Camerini’s films are also sometimes referred to as “white telephone films” or romantic comedies (Landy [1986] 2014, p. ix).. A confrontation with film may have forced opera into a generic conundrum: because Italian operas conventionally presented romantic or melodramatic plots in a historical setting, the separation of these two elements (historical subjects and romantic plots) in film left opera caught between two stools, and could explain why a number of the operas composed during this period avoid romantic plots. Furthermore, operas revolving around a romantic intrigue tend to portray a weak male lover (a tenor) dominated by a femme fatale or a strong father figure. The presence of a weak lover ties operatic protagonists to the weak lovers of on-screen comedies (who also sing), as incarnated by De Sica. Nevertheless, this created a problem because of the inevitable parallel between fictional political leaders and Mussolini, especially in the cases where these unfit leaders are not used to justify a new political order brought on by a strong successor.

Dramas would then seem to be the ideal generic cinematic model for opera under Fascism, seeing as they show both the public and private spheres of political leaders without questioning the leader’s public virility. The attempts to communicate the protagonists’ public virility instrumentally could be opera’s translation of the cinematic technique of expressing the hero’s virility through the adoring eyes of others. However, not only does this instrumental virility exist solely in the protagonist’s absence, but it also fails, as in the case of Antonio e Cleopatra, where Cleopatra’s motif takes over after Ottaviano’s – ending the opera –, or breaks down, as in the case of Basilio’s horseback-riding motif in La fiamma. In Nerone, Mascagni’s attempt at a choral virility contributed to the opera’s negative critical reception (Mallach 2002, p. 274).

Though opera may have tried to represent public virility instrumentally, operatic tradition could not allow the medium to model itself entirely on the cinematic genre of dramas. In Italian opera, male protagonists rarely reform, allowing for the plot’s tragic ending, a norm that developed during the nineteenth century. The conventional need for a tragic ending (generally avoided in films produced during the same period) may have taken precedence over other elements, leaving opera positioned between operatic conventions, the generic distinctions of cinema, and fascist ideology. At the same time, the operas composed during the early-to-mid thirties broke with certain operatic conventions in a way that seems to go against fascist ideology. Though the political leader and weak lover can coincide in opera, operas traditionally present a virile bass or baritone to counterbalance the weakness of the tenor. Nevertheless, the baritones in the operas composed during the early-to-mid thirties are as weak as the tenors. If we think about this change in the context of the rise of film, however, these operatic political leaders could be viewed as a symbol of opera as a medium, suddenly faced with the risk of appearing weak and unfit in comparison to film. Indeed, its protagonists are portrayed as old, unfit, and weak, to be replaced by new youthful successors whose musical expression of virility seems inspired by that used in film.

Another element of operatic tradition that seems to distinguish the medium from film is its fundamental misogyny38This has been widely shown in numerous analyses of operas from the genre’s inception until the twentieth century; however, the first studies to bring attention to this question are Catherine Clément’s seminal Opera and the Undoing of Women (1988) and Susan McClary’s analyses in Feminine Endings (1991).. Of course, films from the period present virtuous and devoted women who remind men of the importance of family life and femmes fatales, temptresses who lead them astray, in accordance with fascist ideals of femininity39The character of Sofonisba in Scipione l’africano has been viewed as an archetypal femme fatale, but each of the movies discussed portrays a woman who seduces (or tries to seduce) the protagonist and distracts him from his duties, opposed to a devoted and virtuous young woman who then leads him back on the right track. For a discussion of the portrayal of women in Italian film under Fascism, see Cottino-Jones 2010, p. 37-52.. At the same time, the virtuous women of comedies and dramas, in their role as saviours of the male protagonists and agents of their reform, are strong and opinionated, especially in dramas. In opera, the women remain in their conventional operatic roles: exotic temptresses (Silvana and Cleopatra) are punished, mothers (Eudossia and La Madre) are guided by a strong love for their sons, and virtuous wives protect their husbands (Porzia and Calpurnia) or die in the attempt (Lucrezia). Perhaps because opera was not amenable to representing women as stronger, its creators had to weaken its male protagonists in response to the greater strength of women in film.

The thirties were also a period characterized by a general crisis of masculinity, partially caused by the new roles and aspirations of women. Film and opera seem to react to this crisis in opposite ways. In film (both comedies and dramas), female protagonists are modern working-women, who have the strength to stand up to men, acting as disciplinary agents that lead renegade men on the path of fulfilling their patriarchal duty. In opera, the only women to have an effect on the male characters are evil femmes fatales, who have to pay for their power with their life. The mother-figures in these operas may resemble the disciplinary agents of film, but in La favola del figlio cambiato “The Mother” uses this power to convince “The Prince” to evade his duty, and in La fiamma, Eudossia’s power is no match for the witchcraft of Silvana, and her son Basilio dies.

In response to the guiding question of this issue, “what can film teach us about music?”, I hope to have shown that the comparison between opera and film at a time of transition in the relationship between the two media allows us to reflect on the workings of each medium and on its changing political role. The comparison with film also reveals that these operas are far from direct and crystallized expressions of fascist rhetoric, struggling as they do with the fascist ideal of masculinity. At the same time, looking at which operatic traditions could be broken (virile baritones) and which are maintained (weak tenors, tragic endings, misogynistic representations of women) allows us to think about what constitute the core components of opera and what could be done away with. One cannot help but wonder whether the male protagonists of opera are not the only ones to suffer from emasculation, but whether the emasculation extends to opera itself.

Bibliography

Scores

Casella, Alfredo (1937), Il deserto tentato, vocal score, Milan, Ricordi.

Malipiero, Gian Francesco ([1933]1953), La favola del figlio cambiato, vocal score, Milan, Ricordi.

Malipiero, Gian Francesco (1936), Giulio Cesare, orchestral score, Milan, Ricordi.

Malipiero, Gian Francesco (1938), Antonio e Cleopatra, vocal score, Milan, Edizioni Suvini Zerboni.

Mascagni, Pietro (1934), Nerone, vocal score, Rome, G. P. Mignani.

Pizzetti, Ildebrando (1935), Orsèolo, vocal score, Milan, Ricordi.

Respighi, Ottorino ([1933]2000), La fiamma, vocal score, Milan, Ricordi.

Respighi, Ottorino (1936), Lucrezia, vocal score, Milan, Ricordi.

Films

Blasetti, Alessandro ([1931]2003), Resurrectio, with Lya Franca, Daniele Crespi, and Olga Capri, DVD, Rome, Cines Pittaluga SA, Ripley’s Home Video Srl, 05397.

Blasetti, Alessandro ([1931]2008), Terra madre, with Sandro Salvini, Leda Gloria, Isa Pola, and Carlo Ninchi, DVD, Replic Milano, in collaboration with the Cineteca di Bologna, Ripley’s Home Video Srl, 05547.

Blasetti, Alessandro ([1933]2007), 1860, with Giuseppe Gulino, Aida Bellia, Gianfranco Giachetti, and Mario Ferrari, DVD, Rome, Cines Pittaluga SA, Ripley’s Home Video Srl, 04567.

Camerini, Mario ([1932]2003), Gli uomini, che mascalzoni, with Vittorio de Sica, Lia Franca, and Cesare Zoppetti, DVD, Rome, Cines Pittaluga SA, Ripley’s Home Video Srl, 03767.

Camerini, Mario ([1935]2003), Darò un milione, with Vittorio de Sica, Assia Noris, and Luigi Almirante, DVD, Rome (Cines), Novella film, Ripley’s Home Video Srl, 03797.

Camerini, Mario ([1936]2003), Ma non è una cosa seria, with Vittorio de Sica, Elisa Cegani, and Assia Noris, DVD, Rome (Cinecittà), Colombo Film, Ripley’s Home Video Srl, 03807.

Camerini, Mario ([1937]2003), Il Signor Max, with Vittorio de Sica, Assia Noris, and Rubi Dalma, DVD, Rome (Cines), Astra film, Ripley’s Home Video Srl, 03787.

Gallone, Carmine ([1937]1993), Scipione l’Africano, with Memo Benassi, Isa Miranda, and Annibale Ninchi, VHS, Milan, Eagle Pictures, Fox Video Italia, 2000415.

Secondary literature

Ameille, Aude, Pascal Lécroart, Timothée Picard and Emmanuel Reibel (eds.) (2017), Opéra et cinéma, Rennes, Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

Basini, Laura (2012), “Alfredo Casella and the Rhetoric of Colonialism,” Cambridge Opera Journal, vol. 24, no 2, p.127-157.

Bellassai, Sandro (2005), “The Masculine Mystique. Antimodernism and Virility in Fascist Italy,” Journal of Modern Italian Studies, vol. 10, no 3, p. 314-335.

Benadusi, Lorenzo (2012), The Enemy of the New Man. Homosexuality in Fascist Italy, Madison, University of Wisconsin Press.

Ben-Ghiat, Ruth (2005), “Unmaking the Fascist Man. Masculinity, Film and the Transition from Dictatorship,” Journal of Modern Italian Studies, vol. 10, no 3, p. 336-365.

Brunetta, Gian Piero (1991), Cent’anni di cinema italiano, Rome and Bari, Laterza.

Casadio, Gianfranco (1995), Opera e cinema. La musica lirica nel cinema italiano dall’avvento del sonoro ad oggi, Ravenna, Longo Editore.

Cavallo, Pietro (1990), Immaginario e rappresentazione. Il teatro fascista di propaganda, Rome, Bonacci Editore.

Celli, Carlo and Marga Cottino-Jones (2007), A New Guide to Italian Cinema, New York, Palgrave Macmillan.

Champagne, John (2013), Aesthetic Modernism and Masculinity in Fascist Italy, New York, Routledge.

Citron, Marcia (2010), When Opera Meets Film, Cambridge, New York, Cambridge University Press.

Clément, Catherine (1988), Opera, or, The Undoing of Women. Translated by Betsy Wing, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press.

Cottino-Jones, Marga (2010), Women, Desire, and Power in Italian Cinema, New York, Palgrave Macmillan.

Crespi, Alberto (2017), Storia d’Italia in 15 film, Rome and Bari, Laterza.

Dalle Vacche, Angela (1991), The Body in the Mirror. Shapes of History in Italian Cinema, Princeton, Princeton University Press.

De Felice, Renzo (1998), Il Fascismo. Le interpretazioni dei contemporanei e degli storici, Rome-Bari, Laterza.

De Grazia, Victoria (1992), How Fascism Ruled Women. Italy, 1922-1945, Berkeley, University of California Press.

De Van, Gilles (1998), Verdi’s Theater. Creating Drama Through Music, translated by Gilda Roberts, Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Dunnett, Jane (2006), “The Rhetoric of Romanità. Representations of Caesar in Fascist Theatre,” in Maria Wyke (ed.), Julius Caesar in Western Culture, Malden, MA and Oxford, Blackwell Publishing, p. 244-268.

Fawkes, Richard (2000), Opera on Film, London, Duckworth.

Flamm, Christoph (2004), “‘Tu, Ottorino, scandisci il passo delle nostre legioni’. Respighis ‘Römische Trilogie’ als musikalisches Symbol des italienischen Faschismus?,” in Roberto Illiano (ed.), Italian Music During the Fascist Period, Cremona, Brepols, p. 331-370.

Frese Witt, Mary Ann (1993), “Fascist Discourse and Pirandellian Theater,” in Jody McAuliffe (ed.), Plays, Movies, and Critics, Durham N.C., Duke University Press, p. 73-102.

Frese Witt, Mary Ann (2001), The Search for Modern Tragedy. Aesthetic Fascism in Italy and France, New York, Cornell University Press.

Gerhard, Anselm (1998), The Urbanization of Opera. Music Theater in Paris in the Nineteenth Century, translated by Mary Whittall, Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Gori, Gigliola (1999), “Model of Masculinity. Mussolini, the ‘New Italian’ of the Fascist Era,” The International Journal of the History of Sport, vol. 16, no 4, p. 27-61.

Grover-Friedlander, Michal (2005), Vocal Apparitions. The Attraction of Cinema to Opera, Princeton, Princeton University Press.

Gundle, Stephen (2013), Mussolini’s Dream Factory. Film Stardom in Fascist Italy, New York and Oxford, Berghahn Books.

Hay, James (1987), Popular Film Culture in Fascist Italy, Bloomington and Indianapolis, Indiana University Press.

Huebner, Steven (1993), “Carmen as corrida de toros,” Journal of Musicological Research, vol. 13, p. 3-30.

Landy, Marcia (1996), Cinematic Uses of the Past, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press.

Landy, Marcia (1998), The Folklore of Consensus. Theatricality in the Italian Cinema, 1930-1943, Albany, State University of New York Press.

Landy, Marcia (2000), Italian Film, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Landy, Marcia (2008), Stardom Italian Style. Screen Performance and Personality in Italian Cinema, Bloomington and Indianapolis, Indiana University Press.

Landy, Marcia ([1986]2014), Fascism in Film. The Italian Commercial Cinema, 1931-1943, Princeton, Princeton University Press.

Leydi, Robert (2003), “The Dissemination and Popularization of Opera,” in Lorenzo Bianconi and Giorgio Pestelli (eds.), Opera in Theory and Practice, Image and Myth, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, p. 287-376.

Locke, Ralph P. (1991), “Constructing the Oriental ‘Other’. Saint-Saëns’s Samson et Dalila,” Cambridge Opera Journal, vol. 3, no 3, p. 261-302.

Locke, Ralph P. (2005), “Beyond the Exotic: How ‘Eastern’ is Aida?,” Cambridge Opera Journal, vol. 17, no 2, p. 105-139.

Mallach, Alan (2002), Pietro Mascagni and his Operas, Boston, Northeastern University Press.

Marlow-Mann, Alex (2012), “Italy,” in Corey K. Creekmur and Linda Y. Mokdad (eds.), The International Film Musical, Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, p. 80-91.

McClary, Susan ([1991]2002), Feminine Endings. Music, Gender, and Sexuality, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press.

Nelis, Jan (2007), “Constructing Fascist Identity: Benito Mussolini and the Myth of ‘Romanità’,” The Classical World, vol. 100, no 4, p. 391-415.

Nicolodi, Fiamma (1984), Musica e musicisti nel ventennio fascista, Fiesole, Discanto Edizioni.

Nicolodi, Fiamma (2004), “Aspetti di politica culturale nel ventennio fascista,” in Roberto Illiano (ed), Italian Music During the Fascist Period, Cremona, Brepols, p. 97-122.

Parker, Roger (1997), Leonora’s Last Act. Essays in Verdian Discourse, Princeton, Princeton University Press.

Pestalozza, Luigi (2004), “Malipiero: oltre la forma. Gli anni della Favola del figlio cambiato,” in Roberto Illiano (ed), Italian Music During the Fascist Period, Cremona, Brepols, p. 401-427.

Pickering-Iazzi, Robin (1997), Politics of the Visible. Writing Women, Culture, and Fascism, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press.

Reich, Jacqueline (2002), “Mussolini at the Movies. Fascism, Film, and Culture,” in Piero Garofalo and Jacqueline Reich (eds.), Re-viewing Fascism. Italian Cinema, 1922-1943, Bloomington and Indianapolis, Indiana University Press, p. 3-29.

Ricci, Steven (2008), Cinema and Fascism. Italian Film and Society, 1922-1943, Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press.

Ségol, Julien (2017), “Opéra et film dans l’Allemagne de l’entre-deux-guerres. Pour une nouvelle poétique du spectaculaire,” in Aude Ameille, Pascal Lécroart, Timothée Picard and Emmanuel Reibel (eds.), Opéra et cinéma, Rennes, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, p. 85-98.

Silvagni, Umberto (1930), Giulio Cesare, Turin, Fratelli Bocca Editori.

Spackman, Barbara (1996), Fascist Virilities. Rhetoric, Ideology, and Social Fantasy in Italy, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1996.

Stenzl, Jürg (1990), Von Giacomo Puccini zu Luigi Nono. Italienische Musik 1922-1952: Faschismus-Resistenza-Republik, Buren, Fritts Knuf.

Stone, Marla Susan (1998), The Patron State. Culture and Politics in Fascist Italy, Princeton, Princeton University Press.

Tambling, Jeremy (1987), Opera, Ideology and Film, Manchester, Manchester University Press.

Wanrooij, Bruno (2005), “Italian Masculinities,” Journal of Modern Italian Studies, vol. 10, no 3, p. 277-280.

Waterhouse, John C. G. (1999), Gian Francesco Malipiero. The Life, Times and Music of a Wayward Genius, Amsterdam, Harwood Academic Publishers.

Wiers-Jenssen, Hans ([1908]1926), The Witch, translated by John Masefield, New York, Brentano’s.

Wyke, Maria (1997), Projecting the Past. Ancient Rome, Cinema, and History, New York and London, Routledge.

Wyke, Maria (1999), “Sawdust Caesar. Mussolini, Julius Caesar, and the Drama of Dictatorship,” in Michael Biddiss and Maria Wyke (eds.), The Uses and Abuses of Antiquity, Bern, Peter Lang, p. 167-186.

| RMO_vol.5.1_Cochran |

Attention : le logiciel Aperçu (preview) ne permet pas la lecture des fichiers sonores intégrés dans les fichiers pdf.

Citation

- Référence papier (pdf)

Zoey M. Cochran, « Virile Condottieri On-screen and Emasculated Heroes on the Operatic Stage. Portraying Male Protagonists in Fascist Italy (1931-1937) », Revue musicale OICRM, vol. 5, no 1, 2018, p. 63-91.

- Référence électronique

Zoey M. Cochran, « Virile Condottieri On-screen and Emasculated Heroes on the Operatic Stage. Portraying Male Protagonists in Fascist Italy (1931-1937) », Revue musicale OICRM, vol. 5, no 1, mis en ligne le 16 mars 2018, https://revuemusicaleoicrm.org/vol5-n1-virile-condottieri/, consulté le…

Auteur

Zoey M. Cochran, McGill University

Zoey M. Cochran is a PhD candidate at McGill University, where she studies the politics of early eighteenth-century drammi per musica created in Italy under Austrian domination. More generally, she focuses on the relationship between opera, Italian language and cultural history, and Italian identity. She has presented at international conferences on topics ranging from the madrigal to Italian fascist operas and her research on the use of Tuscan in eighteenth-century Neapolitan comic opera won her the Proctor prize (2012). She also specializes in Italian lyric diction, which she teaches at the Université de Montréal and the Conservatoire.

Notes

| ↵1 | “Morte ai tiranni! Sii duce tu, Bruto! Uccidere Sesto! E si caccino i re! Muoia! Libertà! A Roma!” All translations in the article are my own. I would like to thank Christoph Neidhöfer, whose seminar on music and politics first inspired this project, Serge Cardinal, who encouraged me to deepen my reflection on the relationship between opera and film, this journal’s reviewers for their generous comments, as well as the many others who read and commented on previous versions of this research, especially Nina Penner, for her careful editing and invaluable comments. |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | Indeed, Flamm discusses how Elsa Respighi used this final chorus to defend her husband from accusations of fascism, whereas Stenzl presents the same chorus as an example of fascist propaganda. |

| ↵3 | The contradictions of fascist ideology and the ambiguities and ambivalence of cultural productions under the Fascist regime have been explored in an increasing number of studies, especially in the last twenty years, by film scholars (Ben-Ghiat 2005, Landy 1986 and 1998, Reich 2002, Ricci 2008), literary scholars (Frese Witt 2001, Pickering-Iazzi 1997), art historians (Champagne 2013), and cultural historians (De Grazia 1992, Spackman 1996, Stone 1998). For an overview of the historiographical debates concerning fascism in Italy, see De Felice 1998. |

| ↵4 | Waterhouse explains that “Malipiero’s three operas of these years [1934-1940] are usually regarded (not without reason, though one must be careful not to underestimate them) as forming a relatively unimportant interlude in his theatrical output, in which he strayed even further from his ‘true path’ as a stage composer than he had done in the last act of La favola del figlio cambiato” (Waterhouse 1999, p. 191). Stenzl focuses on the Roman and imperialistic themes of the operas composed during these years (Stenzl 1990, p. 70, 120-123, 134). |

| ↵5 | “i modelli più obsoleti del passato.” |

| ↵6 | Both Lorenzo Benadusi (2012, p. 296) and Ruth Ben-Ghiat (2005) note a strong shift in depictions of masculinity (which will be the focus of this article) during the Second World War. |

| ↵7 | In Opera, Ideology, and Film, for example, Jeremy Tambling likens the elements of continuity and disruption in the operas of Schoenberg and Berg to the cutting and combining of film sequences (Tambling 1987, p. 75-76). Julien Ségol also discusses the renewing aesthetic effect of cinema on opera in Germany in the interwar period (Ségol 2017). |

| ↵8 | The recent collection of essays Opéra et cinéma (Picard, Rebel, Ameille and Lécroart 2017) begins to break away from this traditional view of the opera-cinema relationship. Nevertheless, most of its essays still focus on the influence of opera on film (discussed in its first and fourth sections) and on on-screen representations of opera (the subject of its third section). Its second and final sections, exploring the interaction between opera and cinema, principally discuss recent works. My research fits into this new line of inquiry, but focuses on the effect of film on opera’s development as a medium, when both were still vying for popularity. |

| ↵9 | Indeed, Barbara Spackman has argued that virility was the “principal node of articulation” of fascist rhetoric (Spackman 1996, p. ix). Recent studies on the importance of virility in Fascist Italy support Spackman’s view (Bellassai 2005, Benadusi 2012, Ben-Ghiat 2005, Champagne 2013, Gori, 1999 and Wanrooij 2005). |

| ↵10 | According to Gian Piero Brunetta, the Istituto luce was nationalized in 1925 for the dissemination of “propaganda and culture through cinematography” (“per la propaganda e la cultura per mezzo della cinematografia,” Brunetta 1991, p. 167). |