Post-Quantization and Glitch in the Music of Nicole Lizée. Nicole Lizée in Conversation with Ben Duinker

Ben Duinker

| PDF | CITATION | AUTEUR |

Abstract

Award-winning composer and video artist Nicole Lizée creates new music inspired by an eclectic mix of influences including the earliest MTV videos, turntablism, rave culture, Hitchcock, Kubrick, Alexander McQueen, thrash metal, early video game culture, 1960s psychedelia, and 1960s modernism. She is fascinated by the glitches made by outmoded and well-worn technology and captures these glitches, notates them and integrates them into live performance.

As a percussionist and chamber musician, I’ve had the pleasure of commissioning, touring and recording Lizée’s music, as well as performing it alongside her. Often synced to films created by the composer herself, Lizée’s compositions require devoted and sustained engagement from performers. This engagement rewards musicians and audiences alike by facilitating a deeper connection with the music––its crafting of the experience of time and stewardship of adrenaline and energy. Lizée gave a keynote address at the second Rhythm in 20th Century Music Conference at McGill University, her alma mater, in September 2023. This interview reflects and elaborates on that talk.

Keywords: composition; glitch; technology; temporality; quantization.

Résumé

La compositrice et vidéaste primée Nicole Lizée offre une musique de création inspirée par un mélange éclectique d’influences, incluant les premiers clips MTV, le turntablism, la culture rave, Hitchcock, Kubrick, Alexander McQueen, le thrash metal, la culture des premiers jeux vidéo, la psychédélie des années 1960 et le modernisme des années 1960. Elle est fascinée par les glitches produits par les technologies obsolètes et usées, qu’elle capture, traduit en notation musicale et intègre dans ses performances live.

En tant que percussionniste et musicien de chambre, j’ai eu le plaisir de commander, de jouer en tournée et d’enregistrer la musique de Lizée, ainsi que de l’interpréter aux côtés de la compositrice. Souvent synchronisées avec des films créés par Lizée elle-même, ses compositions exigent un engagement soutenu et dévoué de la part des interprètes. Cet engagement récompense à la fois les musiciens et le public en favorisant une connexion plus profonde avec la musique – la prise en charge de son expérience du temps et sa gestion de l’adrénaline et de l’énergie. Lizée a prononcé une conférence principale (keynote address) sur sa démarche compositionnelle lors de la deuxième conférence Rhythm in Music since 1900 à l’Université McGill, son alma mater, en septembre 2023. Cette interview reflète et approfondit cette présentation.

Mots clés : composition; glitch; technologie; temporalité; quantification.

Ben Duinker: You grew up in a household filled with broken, semi-broken, semi-fixed, partially functional electronics, due to your father’s employment as an electronics repairer and tester. Your biography mentions a fascination with glitch aesthetics. In that vein, can you elaborate on how this childhood experience has shaped your compositional aesthetic?

Nicole Lizée: For most of his life, my dad has been an electronics repairman, salesman, collector—and, in many ways, a beta tester. By the time I came along, his shop and our house were full of electronics dating as far back as the 1940s. He never threw anything away. Some of these machines didn’t work properly, but as they were analogue, they rarely completely shut down. They entered what I now call the “purgatory phase.” They’re no longer suitable for consumer use because of their erratic behavior, but they still produce sounds and visuals. These were compelling to me from quite a young age. This was the 1970s and 1980s, a technological golden age, which meant my father was being sent new devices probably nearly every week. Those that didn’t work were deemed unfit for consumerism. They didn’t behave according to product specifications. At that point, for me, they were musicalized. Even those that did largely work—i.e., the Atari 2600 console—became a source of sound that I knew would mix well with the “legitimate” instruments around the house like pianos, guitars and drums. For me, the choppy rhythms they produced, the warped pitch, the hums, and distortion—were beautiful music.

B. D.: At that time, we already had John Cage and others who were working to expand the public’s conception of what sounds comprised music; what sounds were musical sounds. Were you aware of any of that at a young age?

N. L.: No, I was not aware of any of this whatsoever. I was quite young, and living in a small town, with finite sources of information. I knew about what was in my basement; it was just me and these broken-down electronic devices amid my “conventional” musical instruments, piano, guitar, and drums. They [the devices] made enticing sounds and visuals—and were highly rhythmic. I wasn’t comparing them to anything. There was certainly no notion of “high art” and “low art.” They just were what they were. I turned the machine on, flicked this switch, turned this knob over here, and pushed this button over there. Sometimes if I held a switch in between the indicators (on an Atari 2600, for example) the machine would behave strangely, which was exciting. It was very unpredictable because the electronic media of the time was highly degradable, but unlike digital it wouldn’t shut down.

B. D.: Because it was mechanical and not digital.

N. L.: Yeah. It continued to work, but not in the way it was intended. I found it beautiful. I quickly became attached to those sounds; they surrounded me and saturated my brain. So, when I started writing music it seemed very natural to include those influences.

B. D.: That seems very à propos for the approach to technology in the hip-hop community at that point. I know that hip-hop influences have, in some way, shaped your compositional practice; were you immersed in that world? I ask because there’s this similar history of repurposing existing technologies, like the sampler, turntable, etc.

N. L.: MTV was a major event in my formative years. I had access to it because the earliest satellite dishes were included as part of the technology that my dad sold and repaired. I started watching MTV in ca. 1982 and quickly became fully obsessed. From 1982–1991. I remember seeing a program in the very early days on MTV (I was maybe 11 years old) about a “scene” going on in New York City that had been going on since the mid-1970s; turntablism/DJs, rapping, breakdancing. Before seeing this program, I had also been playing with record players and scratching records, so it was incredible to see this. But I wasn’t doing what they were doing exactly. I didn’t have a crossfader. I didn’t have the exact equipment. I had records and belt-drive record players because my father sold and repaired these, so I would experiment with scratching and bouncing the stylus off the surfaces of records—using old easy listening records and soundtracks. It was really exciting. So even from that early age, turntablism and sampling have very much shaped my compositional practice.

B. D.: That’s interesting and goes along with the broader idea of you musicalizing the “unmusical” without knowing that Cage and others had been doing something similar. I’m curious about the notion here of the anthropomorphization of technology. Ragnhild Brøvig and Anne Danielsen wrote, in their book Digital Signatures (2016), that “when we emphasize the vulnerable aspects of technology, we humanize the machine” (p. 126). How does that resonate with your use of technology in composition? Do you see humanness in these broken-down devices when you draw inspiration from them, or transcribe the sounds and rhythms they make?

N. L.: Yes, absolutely—from an early age. That is why there is a continued emotional connection. These broken technologies, they were castoffs, right? Embedding them into a piece and treating them as equals among chamber musicians is extremely important. They elicit a certain kind of behaviour from the players; the players must source them, care for them, learn to perform them, and even emulate them—their idiosyncrasies. They are outsiders in the sense that they don’t naturally belong in the concert hall, and they never belonged in the technological world because they refused to behave according to regulations. Or became outdated. There is something emotional about the lost, abandoned, forgotten relic of the past. Once on everyone’s want list and now relegated to a landfill. When machines or media stop functioning the way they’re supposed to for the consumer—they’re no longer useful. So, they begin their new life. It’s a type of freedom. Sometimes they do die in a way—they end up in junkyards and landfills or tossed aside and forgotten, in favour of the digital device. The RCA SelectaVision is a machine that I feel resonates with the above quote and one of my most memorable glitch experiences. This is a machine that didn’t last long on the market as it was severely flawed. These were extremely unstable and degraded the movies quickly. The more they were watched the more deteriorated they would become—but they didn’t shut down—they just sounded and looked more incredible every time. And each video disc/film produced its own specific glitches. It was completely unpredictable, as though it had its own will. It could not be tamed or controlled.

B. D.: How does this all lead to your notion of post-quantization?1Post-quantization refers to control or organization of musical material outside of preconceived logical or realistic conventions or constraints. What is that, and how have you cultivated it as an aesthetic in your compositions?

N. L.: To answer that we have to go back to the broken-down electronics of my youth. I knew that when I wanted to write specifically for them or write in the spirit of what they conveyed, I didn’t want to smooth any edges or simplify anything. I wanted that very sound. It was completely erratic and untamed. It was like nothing else. I wanted the score and performance to be shaped around the malfunction and the performers to take on the elements of malfunction. I didn’t want to alter the score and performance so that it fits within the preconceived notions of what performance or notation should be. So, as I got older, I had to develop some conceptual and notational chops to harness this so as not to compromise anything. This is how post-quantization started for me, and it essentially applies to every aspect of the way I write: the way I construct my scores, notation, orchestration choices, integration and treatment of multimedia, sampling methods and choices, and construction of click tracks. It extends into conceptual considerations; subject matter that could, at a perfunctory “assessment,” be deemed deviant or unsuitable for concert music audiences.

B. D.: Let’s talk a bit more about the challenges of working in a notated medium (i.e. with classical musicians), considering this aesthetic. What sorts of challenges have you encountered in notating exactly what you want to hear (be it unpredictability, malfunction, etc.), and what sorts of strategies, as a composer, have been useful to you in straddling the threshold between extracting precise results from performers and maintaining that sense of spontaneity and/or unpredictability in your aesthetic?

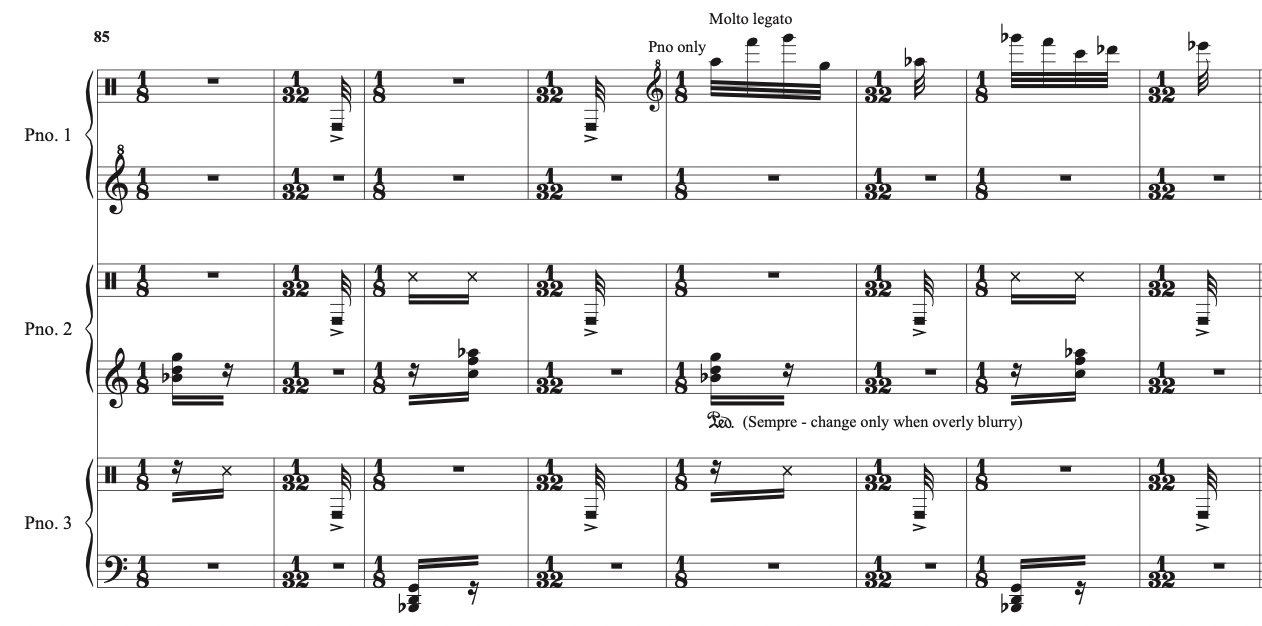

N. L.: The machine sounds must coexist within the ensemble of musicians. Neither entity is going to serve as accompaniment to the other. I want the ensemble to emulate a unique sound, and that demands a certain kind of approach to notation that may seem irrational for some performers, but it’s something I’ve worked on and refined over a long time, and those who have worked with me—globally—have repeatedly expressed to me how logical it is and how it impacts their feel and absorption—and performance—of the music for the better. This includes conductors, percussionists, string players, orchestral players, vocalists, turntablists, etc. There’s a meticulously calculated reason why I notate this way; it’s the only way to capture what these machines do. I could just put everything in four, but it doesn’t mean anything. I would have to alter and compromise the music to fit within the acceptable—or pre-conceived—parameters and that means changing the music and abandoning the source of inspiration altogether. My meter, tempo, and rhythmic choices are not arbitrary (see Figure 1). They serve to capture the source material, the machine, or the spirit of the machine, in all its glitches and malfunctions. I’m always going to include that 1/32 measure, not simply round it down to a “neat and tidy” 2/4. The thought of rounding things down makes me shudder.

Figure 1: Excerpt from Lizée’s Fantasie Impropmptu (2024), showing use of constantly changing time signatures to evoke glitch and malfunction aesthetics.

I remember learning how tempo and pitch were inseparable on the turntable, for example. Increasing the pitch meant simultaneously increasing the tempo. That was something I explored in my first concerto, written as my Master of Music thesis at McGill, for solo turntablist and large ensemble (Lizée 2000). Along with scratch techniques (which were showcased near the end of the work as part of a duel between the turntablist and ensemble), I focused on the speed and pitch aspects of turntablism. I’d have the DJ soloist (DJ P-Love) juggle two records, one playing a whole step higher, which made it higher of course but also a few clicks faster. I did not just want this to happen while the ensemble was doing their own thing, it was integral that these two parties coexist equally: for the turntables to inform the ensemble. Which necessitated everything to be notated, so I devised a notation for the turntables. This meant that the ensemble had to adjust to turntable characteristics: for example, very sudden and relentless shifts in tempo and meter. But at the same time, the turntablist had to—at specific points—follow the conductor. So, between the conductor, the turntablist and the tempi inherent in the records being pared by the turntablist, there are multiple levels of rhythm and tempo occurring simultaneously. There is actually a chapter in the written component of my thesis titled Who’s Conducting Whom?, outlining the multiple levels and juxtaposition of pulse, rhythm, etc. (Lizée 2000). Ultimately, emulating that ethos of how this and other technologies express time and temporality is of the utmost importance.

B. D.: I get the sense, then, that you want this result of musicians because it’s aesthetically coherent with the electronics and there’s simply no other way to achieve it. In that same vein, I’ve had the pleasure of learning and performing several of your works, and I’ve encountered these challenging sequences of measures, tempo changes, and the like. What is the value of the musician going through that process? It reminds me of what Sharon Kanach (2010) has written about learning the music of Iannis Xenakis, that it’s always a negotiation between the performer and score. Does that resonate in any way?

N. L.: At this point in my career, performers generally trust me. From time to time, I will see the look of horror when a performer I’ve never worked with before first sees their part, or I will get an email from a conductor asking me how to go about handling a specifically notated passage, wondering how they’re going to get 40-60 musicians to play an intricately notated glitch rhythm in tandem. I always assure them that it makes sense, to trust the process; it will click, the musicians will feel it together, and it will sync beautifully and transcend beyond “reading the part.” And it always does. Many years ago, during a rehearsal with an orchestra, the conductor decided to try to re-meter a section that was in multiple meters, into 4/4. It didn’t work. The conductor then decided to revert back to way I initially wrote it and it clicked. The concertmaster looked at me, nodded and smiled. This initial doubt happens rather infrequently now because more performers and ensembles are familiar with my aesthetic and have heard my works performed. They know it can be achieved and have faith that the process works and is worth it. And, really, performers who program my music or commission a new work from me are seeking this experience. I call it “going down the rabbit hole” or “going through the portal.” I’ve spoken so frequently with musicians who have experienced it, and actually want to discuss it in-depth afterward because it resonated with them. And they want to perform it or experience it again. This is profoundly meaningful to me. And while I do very much enjoy working with performers for the first time, I love forging ongoing musical partnerships with performers who want more. It means expanding the scope of possibility even further and that is, ultimately, what it means to be an artist. My music may not be easy to sightread or, for lack of a better word, under-learn. You have to spend time with it. And everybody does that together [in chamber contexts]. It’s more than simply lining up; it has to be felt together. I know the process is stringent, lining up with my click tracks, navigating the changing meter, tempo, or what have you. But once that’s absorbed by the players, the issues evaporate. It goes beyond reading the notes; their gestures and bodies begin to react in similar ways, to those, say, extra 32nd-note measures, etc. Their body reacts, their mind reacts, and it becomes hyper-expressive. Everyone executing it together. So, if I were to take out those measures and essentially dilute everything, that would be quantizing. That intrinsic dimension—that depth of concept—would be lost. This obliterates my expressiveness—my voice—and that begs the question: why bother creating if it needs to be watered down in order to be accepted? The artists I’ve always admired are those who broke new ground, took creative risks, regardless of the initial naysayers.

B. D.: Let’s talk about the “extended bar” and the “black frame,” because these are both important fixtures in your approach to time and temporality, and there’s a relation back to technology here too, right?

N. L.: Yes, I like to play with the “frames” or the “parameters” or the “box” of notation, where it’s like a schematic.2Playing with the frames refers to both the black frame in stop motion animation and what occurs when frames (specifically i-frames and d-frames) are either removed or duplicated in video manipulation, resulting in damaged or corrupted video (also referred to as “datamoshing”). If you want to have something perfectly logical, then yeah, it’s going to behave like a well-oiled machine, very rationally, and that’s fine. But if you want to go somewhere else, which is what I want to do, then I’m going to “solder” it a little differently and put a connection somewhere else. And that’s how I look at the score. So, it’s kind of hacking. I look at it almost as hacking the communication between score and musicians. I know they will react to this approach. It’s a deep way of communicating with players, it will affect everything; their ears, body language, the way they practice, the way they count. I think about the black frame often. Drawing inspiration for a musical work from a nonmusical source— particularly something tech, design, or concept based—is a way I like to work. Disassembling these to study their circuitry and create reinterpretations of them stirs up the imagination. In this case, the source is stop-motion animation. I’ve spent a lot of time creating stop motion for my video work and it’s deeply affected the way I write music. Central to stop motion is the black frame where the “trickery” is carried out, unseen. Motion is made possible by interruptions in the chain of images. During these interruptions the animator modifies the objects off-camera in tiny increments, which the audience does not see. The darkness is necessary to create the illusion of continuity. But the events during those unseen moments, which can extend for an indefinite amount of time, can be just as interesting. I’m particularly intrigued by the earliest stop-motion—created without the use of computers; very analogue, hands-on, and inventive. Referencing this sonically, the musical material that is placed in the black frame—or the bar line, by “thickening” or “stretching” it—will interrupt the chain of motion. And a great deal hinges on what is placed in that frame; it will distort or alter the way the material is perceived, felt, and performed. The click track plays a role in this. It’s a way to lure the player. Kind of like an erratic doppelgänger or “devil on the shoulder.”

B. D.: So true! Yes, because click tracks are this hidden entity. Do they enable us to do something in the temporal domain that is simply impossible without them? And if so, what does that say about what we’re doing? For example, many of your pieces contain extreme and/or sudden tempo variations, ones that could take a very long time to learn…

N. L.: The click is so many things. There are soloists who learn my pieces with the click but ultimately abandon the click after a period of time with it because the click has, in some sense, infiltrated the player. The player has now joined forces with the click, the machine; they are humanizing one another. In those cases, the musician has gone to this new dimension with the click and is behaving differently. This depends on the piece of course, and the size of the ensemble. Some players enjoy it being there because of its erratic, doppelgänger sensibility. It’s another performer relentlessly encouraging everyone to keep going; to keep fluctuating meters and tempi. It’s the fun—but slightly crazed—friend at the party. To answer your question about whether it’s impossible to achieve this rhythmic aesthetic without it: possibly initially. It’s the facilitator that can change the performer’s scope of temporal possibility. After that—and this is what I have noticed when I work with performers multiple times—the performer assesses and absorbs the music differently and arguably more quickly. It’s like learning code. Difficult—maybe even inaccessible—at first but then it’s merely an expansion of language.

B. D.: I can relate to that. I can recall many moments when playing your music where I’ve found myself grooving to a click track that only I and the other performers can hear. Like, it’s literally there to keep me on track and in time, but I’m also engaging with it in what feels like a bilateral way, almost like I’m grooving with it.

N. L.: Right, yeah I know what you mean. It’s definitely more than simply functional. When I was beginning with clicks, I didn’t think about them as conventional clicks because there was so much erratic energy in them—they were malfunctioning, in a way; not unlike the machines I grew up with. For example, they didn’t have two tones to indicate downbeats, but at one point, the Kronos Quartet asked if I might add them, and since then I have added the two tones, but kept the erratic energy.

B. D.: I’m interested in hearing what you want your audiences to know and to not know. How much of your compositional practice, process, approach, do you want kept secret to the public, or to put it another way, how much do you want them to know? I’m thinking specifically here about instances where you display parts of your scores in your films [that audiences see], but we can speak about this more generally too.

N. L.: I think the first time I did this [show a score or sketch in a film] was in my orchestral multimedia piece, Arcadiac (2005/2007) (Video 1). It involved my playing and transcribing vintage glitching arcade games, and I included the notated results in the video for the audience to see. I wanted the written music, in its artefact status, to infiltrate the experience of the piece, to link to the sound and performance. This forms another portal into connecting with the work.

Video 1: Excerpt of the video created for Arcadiac (2005/2007).

Transcription is a major part of the preparation, and it’s not as though I’m transcribing something logical; it’s glitch—it’s demented, and the notation is a graphic representation of what this looks like. And seeing this feral notation—what the performers are reading from their scores—adds to the multi-sensory experience. Soon after this initial inclusion of scores in the video I started to hack them. I displayed the process of physically engaging with the scores and clips by using the screen as a canvas and painting over them. I also manually altered printed stills from the scene, where a 2D paper still from the video is literally cut into and opened to reveal 3D textured substances beneath (Video 2). The clips and notation become tactile materials.

Video 2: Excerpt of the video created for Sasktronica (2017).

I have also always associated scores with schematics, and this goes back again to the electronics of my youth. Each one of the devices that my father repaired had its own schematic drawing that mapped all the inner components. These drawings are intricate and beautiful, akin to musical scores. They visually detail the correct way the electronic device is supposed to behave, just like a score visually details how a piece is supposed to behave—each with all its minutiae. And someone had to go to the trouble of creating this elaborate map of the device (and the score!)

So, much like schematics and inner circuitry are revealed and ready to be hacked, I think of scores like schematics ready to be hacked. Both can be rewired and circuit bent. I like the way Black MIDI scores work.3The practice of creating the densest scores possible in Finale or a DAW so as to crash it when playing the scores through the MIDI player. I created an entire multimedia piece for the Toronto Symphony and Kronos Quartet as soloists (Black MIDI, 2017) based on this phenomenon. I also like the idea of pareidolia, or hidden messages in scores. So, much like film, tape, electronics, I also started messing with the scores; purposely manipulating them to diverge from what happens in the music. Or to create a quasi-narrative using just the physical appearance of the scores. For me this is an especially crucial element of how the music manifests itself or is presented to those who perform or listen to it. Circuit bending all aspects of presentation.

Directly referencing your question about how much I like to reveal to the audience: with everything that’s created digitally and online—in the cloud—without tangible interaction, I increasingly gravitate toward not only showing, but actually emphasizing, the process. The scores, schematics, physical devices, revealing what goes on behind the scenes in stop-motion animation, using analogue means to create video effects (manipulating paper stills and flip books and physically painting the screen) rather than digital. I love the roughhewn, hands-on tactility of it. And I like to reveal this to the audience as a form of subversive artistic expression. Not as an informative and accurate behind the scenes, “how does this work.” Again, nonfunctional, abstract, and erratic.

B. D.: What have you learned from audiences about how they perceive or apprehend the passage of time in your music? We have spoken about how the fallibility and humanness of analog electronics create these aberrations in the smooth, linear flow of time, and how those imperfections find their way into your compositions through elements like the extended bar, or sudden and extreme tempo and meter changes. I can think about the moment in your work Hitchcock Etudes (2010) where you have used the scene in Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963) where the school children are running down the street while the birds chase and peck at them. Musically in that moment the audience feels as though they are stuck on a repeating loop, unable to move forward, and this corresponds to a similar feeling in the film, where the children cannot escape the birds. But more broadly than this example, what have you heard from audiences about their take on time and temporality in your music?

N. L.: That is a great question. I like to pluck short moments in a film from their functional narratives, elongate them, and allow them to live outside of themselves in a void or vacuum; to exit their prescribed roles for a while. This is what I do in several of my film-based études, but this excerpt you’ve mentioned is a good example of it. It’s a very short scene. It’s fast-paced. Tippi Hedren and the school children need to run as quickly as possible from the killer birds so as not to die. But I’ve extended this short clip by several minutes so it can be experienced much differently in terms of temporality and cognizance. Referring to my earlier analogies, this could also be thought of as entering a portal—or a purgatory—before snapping back to its original objective at the end of the piece. Except, the narrative or pacing of the plot is arguably lost or certainly hacked. I like the idea of existing within a scene where nothing functional happens—where narrative and chronology is no longer the core objective. Even playing video games, I am much more interested in spending time in a room or scene within the game, enjoying the surroundings and sound design, although there are tasks to do, points to accumulate, or pursuers to run from. This suspends time in a way—I detach from the gameplay and experience it aesthetically on my own terms; not the way in which the game creators intended. It’s a bit like the malfunctioning devices from my youth that didn’t behave according to factory specifications, and so were liberated.

I do like to build continuous, long-form pieces that twist and spiral within a certain framework or domain and then morph into another. And I carefully consider the transitions between the domains quite a lot. There are moments of very calculated metric modulation and moments of interjections eventually taking over, referencing the black frame I was describing earlier.

Audience members will often speak to their experience of my longer, continuous pieces. My percussion concerto written for Colin Currie, Blurr is the Colour of My True Love’s Eyes (2022), is a long piece, but people told me they felt transported, hanging on for dear life, unsure of what was coming next—but captivated and on board for the ride. And at the conclusion they were unaware that the duration was over 35 minutes. This has applied to other pieces and performances I have done, which can last one hour or more without a pause.

B. D.: Yes, I have been on stage with you for some of those!

N. L.: Yes! It’s something I learned to some extent from rave culture. Even before I went to raves; when I had only read about what a rave was—how it worked, and how it was meticulously constructed. It intrigued me; DJs could determine what should happen to peoples’ emotional states at any given time, so they would build an exceedingly long set, with predetermined peaks and valleys, and specific BPMs. This idea of being able to control that pacing has found its way into my longer compositions especially. Operas, orchestral works, pieces with video: for me, it is about sparking excitement about going on that odyssey with me, without ever predicting where it will end up, but knowing it was carefully constructed and being completely on board. For me, it hearkens back to the trusty SelectaVision and that idea that you never really knew what you were going to get when you watched something on that machine, but it was always captivating and unforgettable. I loved that. The RCA SelectaVision: the original rave.

Bibliography

Brøvig-Hanssen, Ragnhild, and Anne Danielsen (2016), Digital Signatures. The Impact of Digitization on Popular Music Sound, Cambridge, MA, MIT Press.

Kanach, Sharon (ed.) (2010), Performing Xenakis, New York, Pendragon Press.

Lizée, Nicole (2000), RPM. For Large Ensemble and Solo Turntablist, Master’s thesis, McGill University.

| Article_RMO_12.2_Duinker |

Attention : le logiciel Aperçu (preview) ne permet pas la lecture des fichiers sonores intégrés dans les fichiers pdf.

Citation

- Référence papier (pdf)

Ben Duinker, « Post-Quantization and Glitch in the Music of Nicole Lizée. Nicole Lizée in Conversation with Ben Duinker », Revue musicale OICRM, vol. 12, no 2, 2025, p. 213-224.

- Référence électronique

Ben Duinker, « Post-Quantization and Glitch in the Music of Nicole Lizée. Nicole Lizée in Conversation with Ben Duinker », Revue musicale OICRM, vol. 12, no 2, 2025, https://revuemusicaleoicrm.org/rmo-vol12-n2/Nicole-Lizee-in-conversation-with-Ben-Duinker/, consulté le…

Auteur

Ben Duinker, McGill University

Ben Duinker is a researcher with the McGill-based ACTOR Partnership, a multi-institution organization dedicated to the study of timbre and orchestration. He previously held a SSHRC (Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada) Postdoctoral fellowship to study analysis and performance of contemporary music at the University of Toronto. Since receiving his PhD in Theory and MA in Percussion Performance from McGill University, Duinker has published widely on a variety of topics, and performs, records, and tours as a chamber musician.

Notes

| ↵1 | Post-quantization refers to control or organization of musical material outside of preconceived logical or realistic conventions or constraints. |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | Playing with the frames refers to both the black frame in stop motion animation and what occurs when frames (specifically i-frames and d-frames) are either removed or duplicated in video manipulation, resulting in damaged or corrupted video (also referred to as “datamoshing”). |

| ↵3 | The practice of creating the densest scores possible in Finale or a DAW so as to crash it when playing the scores through the MIDI player. |