Meter in Contemporary Jazz. A Practitioner-Based Approach

Andres Orco

| PDF | CITATION | AUTHOR |

Abstract

Jazz has a strong groove-based tradition that uses a stable meter and exhibits a significant degree of metric dissonance. Recently, the prevalence of metric multivalence stemming from conflicting acoustic signals has risen exponentially. This phenomenon, historically manifested between an improvisor’s solo and the piece’s repeating formal structure, has also become an aesthetic feature of the composition itself. In this essay, I highlight contemporary jazz pieces that afford listeners multiple metric interpretations and often lead to considerably different approaches to structure and groove. I propose an ecologically valid analysis that more closely aligns with the way practitioners approach the repertoire, and I demonstrate how these techniques build upon the Afro-diasporic and improvisational tradition of jazz. I contextualize these developments with an ethnographic study where I interviewed fifteen professional jazz musicians, uncovering consistent thought processes, musical training, and performance practices that appear foundational to develop an enculturated understanding of contemporary jazz.

Keywords: entrainment; jazz; meter; metric dissonance; rhythm.

Résumé

Le jazz relève d’une forte tradition basée sur le groove qui utilise une métrique stable et présente un degré important de dissonance métrique. Récemment, la prévalence de la multivalence métrique, résultant de signaux acoustiques contradictoires, a connu une croissance exponentielle. Ce phénomène, historiquement observé entre le solo d’un improvisateur et la structure formelle répétitive de la pièce, est également devenu une caractéristique esthétique de la composition elle-même. Dans cet essai, je mets en lumière des pièces de jazz contemporaines qui offrent aux auditeurs de multiples interprétations métriques et conduisent souvent à des approches considérablement différentes de la structure et du groove. Je propose une analyse écologiquement valide, plus proche de la manière dont les praticiens abordent le répertoire, et je démontre comment ces techniques s’appuient sur la tradition afro-diasporique et improvisée du jazz. Je contextualise ces développements par une étude ethnographique au cours de laquelle j’ai interviewé quinze musiciens de jazz professionnels, révélant des processus de pensée, une formation musicale et des pratiques d’interprétation cohérents qui semblent fondamentaux pour développer une compréhension inculturée du jazz contemporain.

Mots clés : dissonance métrique ; entraînement ; jazz ; mesure ; rythme.

Introduction

Standard repertoire in jazz features what Love (2013) calls a “scheme:” a predetermined formal structure with a fixed number of measures in duple or triple meter.1Love (2013) refers to the schematic organization of jazz from the Great American Songbook, bebop, and hard-bop substyles. These styles account for most repertoire studied in scholarship. While performers can deviate significantly from the harmony in their improvisations, the metric structure is maintained to facilitate ensemble performance. This does not mean that metric rigidity leads to rhythmic sterility. On the contrary, stable metric frames enable musicians to improvise highly sophisticated rhythmic material against the form. Because of their widespread use across the repertoire, formal schemes became an embedded feature in jazz, and experienced listeners learn to expect them (Love 2013). What happens, then, when metric schemes are not perceptible? Or when the piece can be heard in multiple ways? This is the case in much of twenty-first century jazz, where metric dissonance is generated not only by a rhythmically complex improvisation but also by a metrically ambiguous compositional structure.2In what follows, I present each analysis with an accompanying musical excerpt and a YouTube link with the entire piece discussed. To situate the passages with their surrounding metrical context, I highly encourage the reader to listen to the pieces in their entirety.

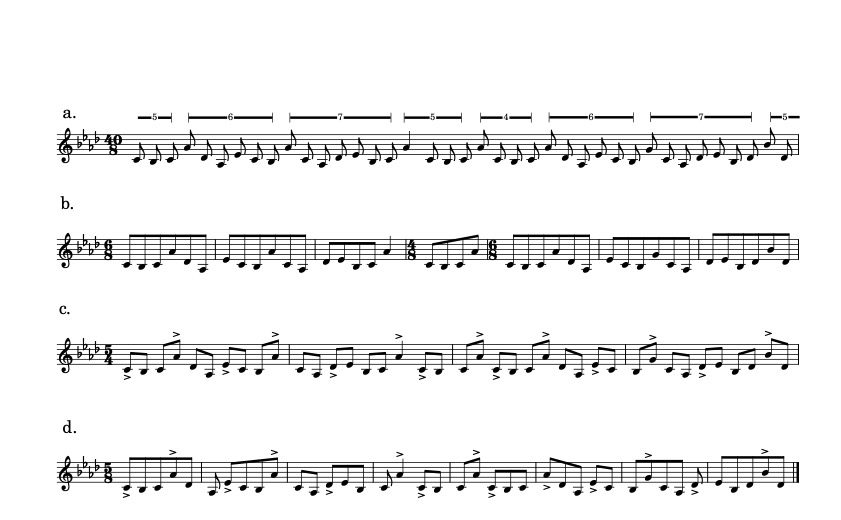

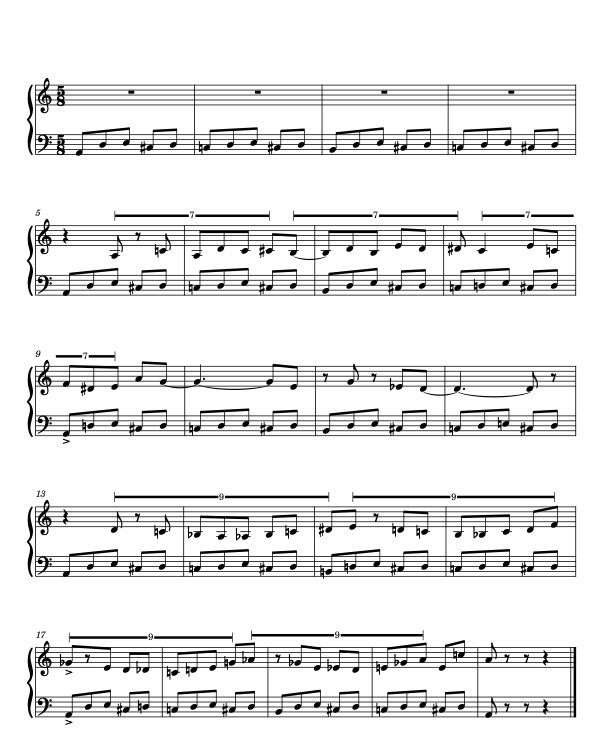

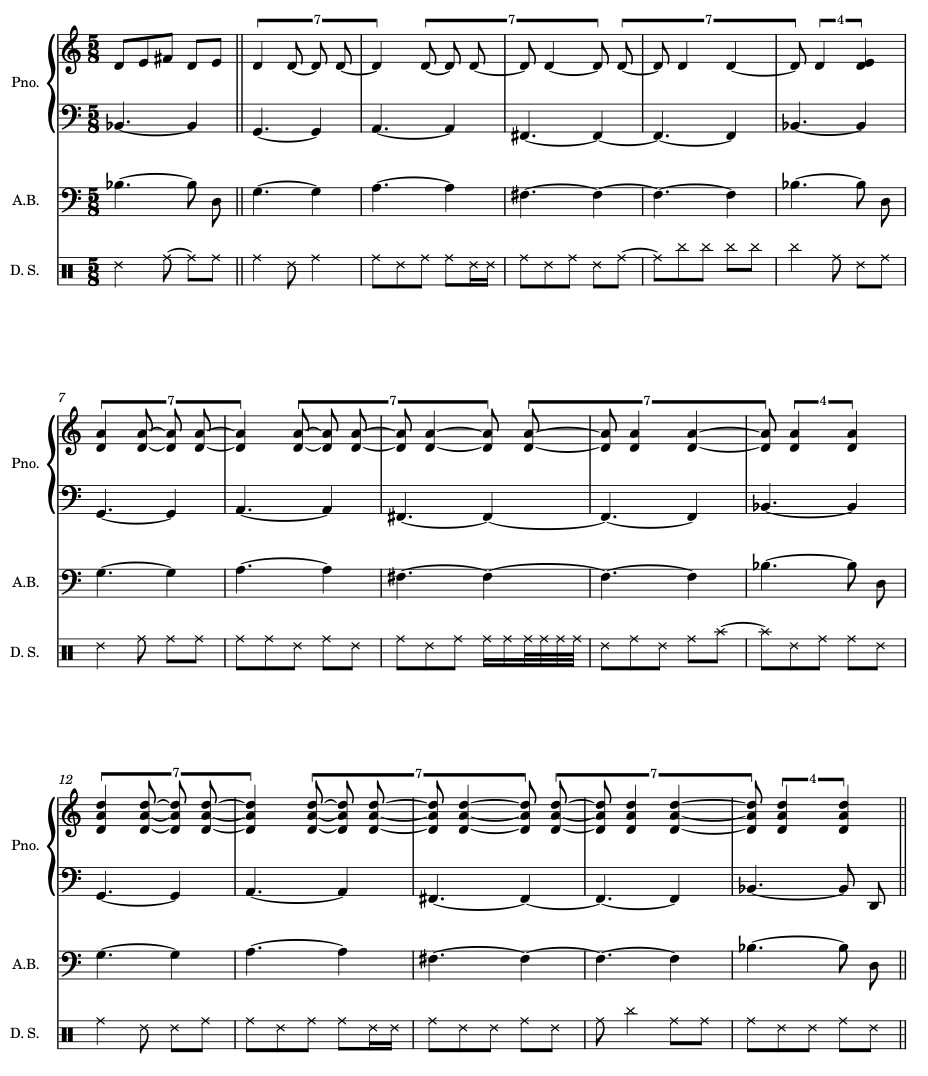

Figure 1: Grouping possibilities for the ostinato in “New Maps.”

Media 1: Solo piano introduction in Tigran Hamasyan’s “New Maps.” Listen to Media 1.

Tigran Hamasyan’s “New Maps” from the A Call Within (2020) illustrates some of these aesthetic and formal developments.3 See Hamasyan (2020) for the complete audio track, available through this link. Figure 1 presents the introduction, which features an ostinato cycle of 40 eighth notes.4 Except for Patrick Zimmerli’s “Pendulum” (Figure 8), all notated figures are my own transcriptions. The ostinato can be grouped in many ways. The highest pitches (Ab – G – Bb) form the melody and organize the phrase into groupings of 6 + 7 + 5 + 4 + 6 + 7 + 5.5 Note that the last grouping of 5 starting with the Bb continues into the beginning of the ostinato. Figure 1b presents a bottom note approach that segments the ostinato based on the accented low notes (C – Eb – D – C – C – Eb – Db). This interpretation creates groupings of 6 + 6 + 6 + 4 + 6 + 6 + 6 and can be notated as a seven-measure mixed meter phrase.

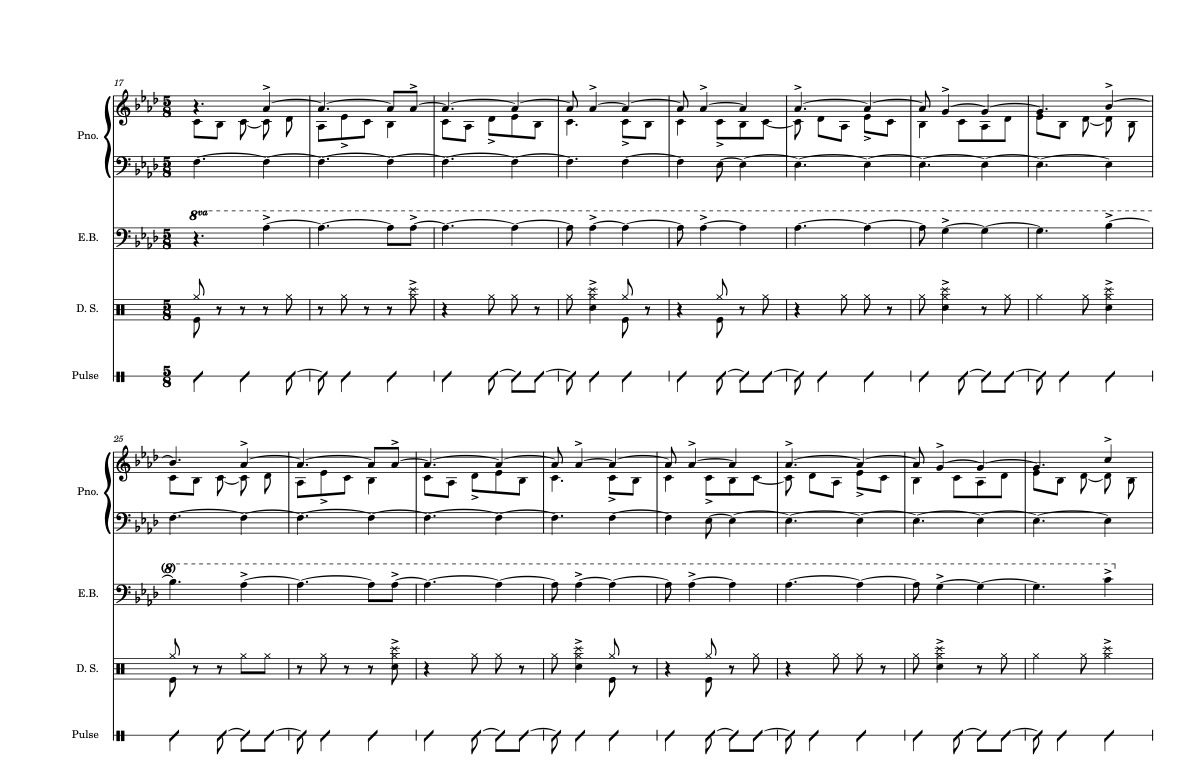

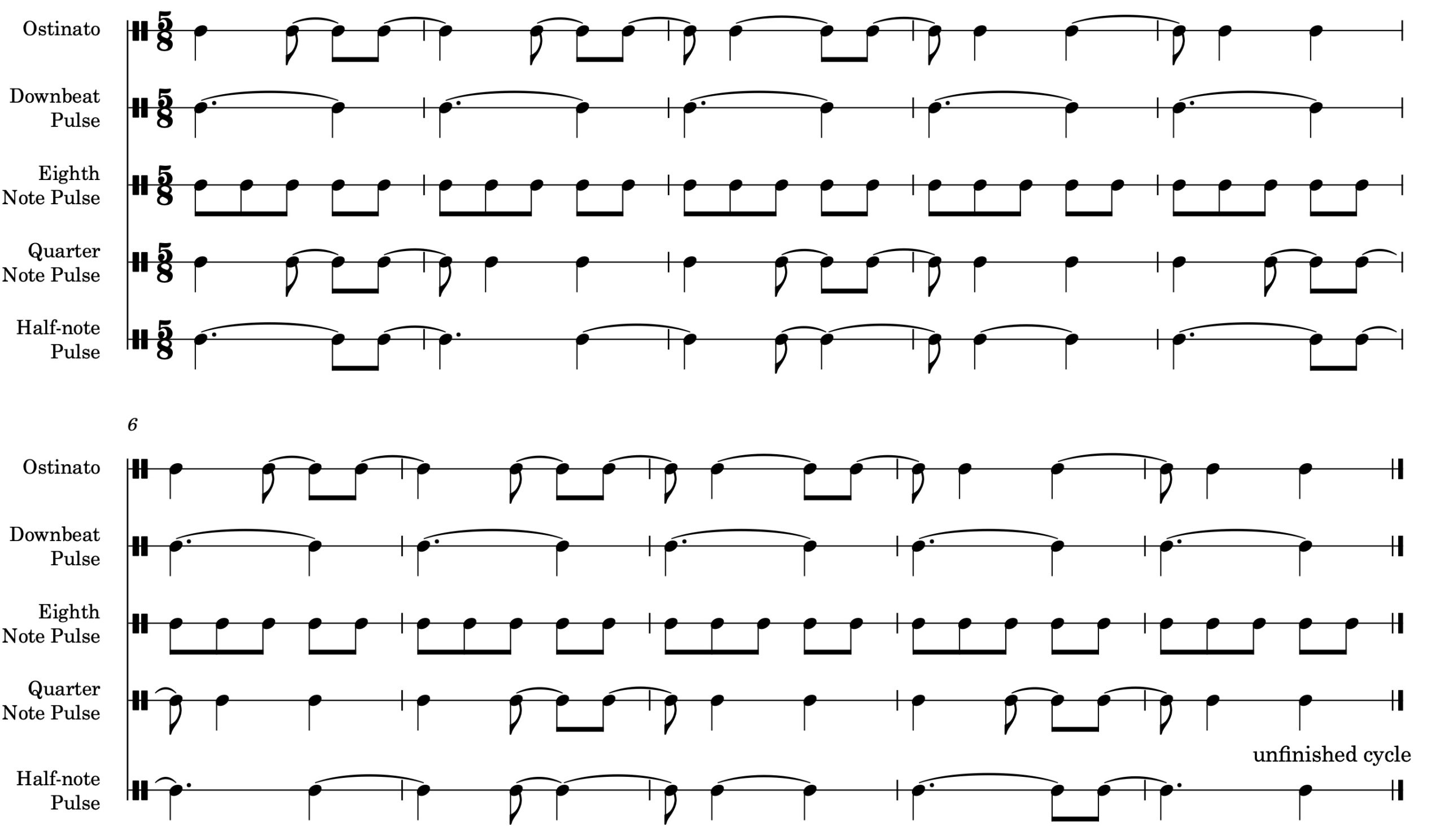

I offer two other interpretations that might seem, at first glance, unsupported. Figure 1c and 1d exhibit unchanging meters with four- and eight-measure hypermeter, two prototypical characteristics in the repertoire that continue to appear in contemporary examples—albeit in a more obfuscated manner.6Large-scale hypermetric structures that maintain an underlying unchanging meter in favour of local measure-to-measure metric dissonance have also been found in popular music, such as EDM, rock, and metal. See Butler (2006), Pieslak (2007), Biamonte (2014), and Lucas (2018). These interpretations, though not clearly aligned with the musical surface, become more salient once the drums enter (Figure 2). The groove largely follows the melody, but the “pulse” staff in Figure 2 demonstrates that the drums also consistently align with the quarter note and half-note of quintuple-based meters.7I notated Figure 2 in 5/8 instead of 5/4 because the rest of the piece—the music beyond the excerpted example—can be heard and notated more clearly in 5/8. Hamasyan’s introductory statement affords many possible metric hearings, and later contextualizes it in 5/8, the main metrical context of the piece. While this orientation requires some perceptual stubbornness in dismissing the gravitational pull of the melody, we can maintain a consistent and steady beat that neatly fits the whimsical character of the ostinato into a metrically stable frame.

Figure 2: “New Maps,” mm. 17-32.

Media 2: Continuation of the “New Maps” introduction where the piano is joined by the bass and drums. Listen to Media 2.

There is certainly no correct hearing of “New Maps.” A central aesthetic quality is the affordance to interpret the rhythmic counterpoint in multiple ways. In this essay, I highlight pieces in contemporary jazz that afford multiple metric interpretations, which often lead to considerably different approaches to structure and groove. I also propose an analysis that closely aligns with the way practitioners approach the repertoire. In doing so, I demonstrate how these pieces connect to the Afro-diasporic improvisational tradition of jazz, and I contextualize the analysis with findings from an ethnographic study involving fifteen professional jazz musicians. Including the expert practitioner’s perspective in theoretical studies is ethically valuable and provides ecological validity to a discussion of their music.8Ecological validity is a common term in psychological research used to describe the relationship between a study’s methodologies and conclusions—often determined in controlled lab environments—to the study’s population out in the real world. A study that can more closely generalize observed human behaviours in the real world is considered more ecologically valid. My interviews uncovered consistent thought processes, musical training, and performance practices that appear foundational for developing an enculturated understanding of contemporary jazz. A practitioner-based approach highlights the enduring prominence of meter but also suggests a more flexible system of metric processing involving pulses and rhythms as potentially metric entities.

Meter in Jazz

Scholars have treated meter in jazz as an underlying structure that enables the interpretation of rhythm (Love 2012). This framework establishes meter as a set of alternating strong and weak pulses at different subdivision levels that interact to create a hierarchic structure (Yeston 1976). Lerdahl and Jackendoff (1983) built upon this model and developed a highly influential theory that separates meter (metric structure) and rhythm (grouping structure) into distinct entities, and outlines “well-formedness” rules necessary for meter to emerge, such as isochrony and beat representation across hierarchic levels. Metric hierarchy is often viewed as a fundamental characteristic of jazz, and scholars have suggested that metric depth extends to large-scale hypermetric organization that structurally divides into sections of four, eight, or sixteen measures (Waters 1996, Love 2013). Many jazz scholars have focused on how grouping structure interacts with metric structure, which historically manifests in the superimposition of an improvisor’s solo against the unchanging formal structure of a piece.9See Folio (1995), Waters (1996), and Downs (2001). Harald Krebs’ (1999) taxonomy for metric dissonance has been widely used by jazz scholars, such as Larson (2005) and Love (2013), to differentiate between subliminal and direct displacement and grouping dissonances. From this viewpoint, jazz’s metric context is influenced by a structurally deep figure-ground relationship predicated on the way rhythm dynamically interacts with a stable meter.10Pressing (1984) theorizes that jazz improvisation involves the interaction with and against a referent, “an underlying formal scheme or guiding image specific to a given piece” (p. 346).

Other scholars dismiss the separation between rhythm and meter. Hasty (1997) treats meter as a special quality of rhythm that emerges from a listener’s expectations of the future based on previously heard events. A rhythm’s duration has projective capabilities that, when consistently met, lead to rhythm’s “mensural determinacy.”11Mirka (2009) and Yust (2018) build upon Hasty’s work within the context of Western art music. Stover (2009 and 2023) and Michaelsen (2023) elaborate projection theory in jazz and Afro-diasporic music through the lens of improvisation and call-and-response. Meter as a projective enterprise aligns closely with scholarship in the cognitive sciences that empirically studies music perception. Justin London’s Hearing in Time (2012) situates meter as a mental capacity predicated on entrainment: the cognitive and sensorimotor ability to synchronize to external stimuli. Meter is the result of an error-detection process that interprets information to create a predictive model where expectancies are either met or deviated from in the acoustic signal. Infrequent deviations do not necessarily destabilize entrainment, but sufficiently disturbing inputs warrant metric revision (Large and Snyder 2009). Disturbances to entrainment trigger the error-detection process to either steadfastly adhere, successfully or not, to the previous synchronization or to synchronize to the most salient acoustic signal.12Imbrie (1973) differentiates between “conservative listeners” who preserve the previous metric context and “radical listeners” who adapt to the conflict input in favour of a new meter. This framework rests on varying predispositions to metric dissonance, and scholars have focused on musical instances that exhibit multiple “metric states” emergent from different pulse streams (Cohn 2001, Leong 2007, and Murphy 2009). Through the lens of music psychology, meter is a perceptually limited behaviour that is also a highly trainable and context-specific skill.13London’s (2012) Many Meters Hypothesis speculates that “metric competence resides in […]knowledge of a very large number of context-specific metric timing patterns. The number and degree of individuation among these patterns increase with age, training, and degree of musical enculturation.” (p. 182).

Historically, jazz’s connection to dance and groove-based music engendered a rigid metric regularity that rarely challenged established metric states. Listeners can quickly identify and maintain a piece’s metric context, and Love (2013) argues “a knowledgeable listener assumes that a fixed metrical hierarchy […] will persist throughout” (p. 49). While a rhythmically inventive improvisation or highly syncopated melody can be destabilizing, a listener understands the conflicting perceptual input does not signal metric change and, with sufficient acoustic signals, such as the drums and bass, the listener can re-synchronize if they get lost. This affordance, however, has lessened in the repertoire after 1960. Pieces exhibit unusual forms and irregular hypermetric structures, such as five- and seven-measure phrases (Waters 2019). Abandonment of common metric schemes is even more prevalent in late 20th- and early 21st-century jazz, which has received comparatively little attention in scholarly discussions.14Hannaford (2017) analyzes the improvisational spaces of five contemporary jazz compositions by current female composers, all of which exhibit mixed meters and irregular phrase lengths. Both Schumann (2021) and Boyle (2021) discuss the structural importance of ostinati, asymmetrical meters, and metrically malleable passages. Asymmetrical meters, polymeter, and metrically malleable ostinati centre metric dissonance as a compositional aesthetic in recent jazz.15London (2012) defines metric malleability as “a property by which melodic or rhythmic patterns may be heard in more than one metric context” (p. 99).

A knowledgeable listener thus cannot fully rely on the same metric conventions as previous styles to disambiguate the musical surface of contemporary repertoires. In the following discussion, I demonstrate how the previous metric contexts of stable meters and large-scale hypermetric structures continue to appear in the repertoire, albeit in obfuscated ways. I argue that this repertoire exhibits what Cohn (2020) calls “metric co-existence,” a quality emergent from the psychological concept of bistability, where multiple metric orientations are present and share a “zone of possible time points when the meter might tip or flip” (p. 223).16Cohn (2020) follows Leong (2011) who visualizes shifts from one metric orientation to another through a displacement continuum. Whether these metric states can be entrained simultaneously is outside the scope of this paper. I refer to the co-existence of metric orientations simply as an objective phenomenon of the musical surface, not as a perceptual capability of the listener or performer. I aim to demonstrate that this spectrum of possible metric states is a performance practice that musicians employ in jazz. This capability is refined through years of context-specific training and is constituted by a kind of metrical processing that involves both the referential structures and metric qualities of meter and rhythm.

Metric Training in Jazz. An Expert Practitioner’s Toolkit

In the fall of 2022, I interviewed 15 professional jazz musicians who have expertise in rhythmically complex contemporary jazz.17I am deeply grateful to the musicians for participating in the ethnographic study; they kindly gave me permission to use the video and interview content as part of this research. While ethnographic work in jazz is not uncommon, studies generally focus on discussions of improvisational practice, substyles, oral histories, and critical theory.18See Berliner (1994), Monson (1996), and Porter (2002). I focused on a discussion of rhythm, and its practice and manifestations in contemporary jazz musicians’ compositions and improvisations. The interviews were part of a study approved by the University of Colorado Boulder Institutional Review Board (IRB protocol: 22-0404). After providing informed consent, the musicians listened to Patrick Zimmerli’s “Pendulum” from Clockworks (2017) without a score and then answered questions about their training and thought processes. I met virtually with each participant using the video conferencing platform Zoom. Interviews lasted about 60 minutes. The participants were not recruited based on a specific type of jazz played but on my subjective determination of their rhythmic capabilities informed by my own experience as a jazz musician. Each participant is an accomplished composer and performer with several albums as a leader and collaborator. All are performing and touring musicians who continue to release new music. To my surprise, some of the most respected people in the field agreed to participate. I spoke with Grammy winners and several McArthur and Guggenheim Fellows.

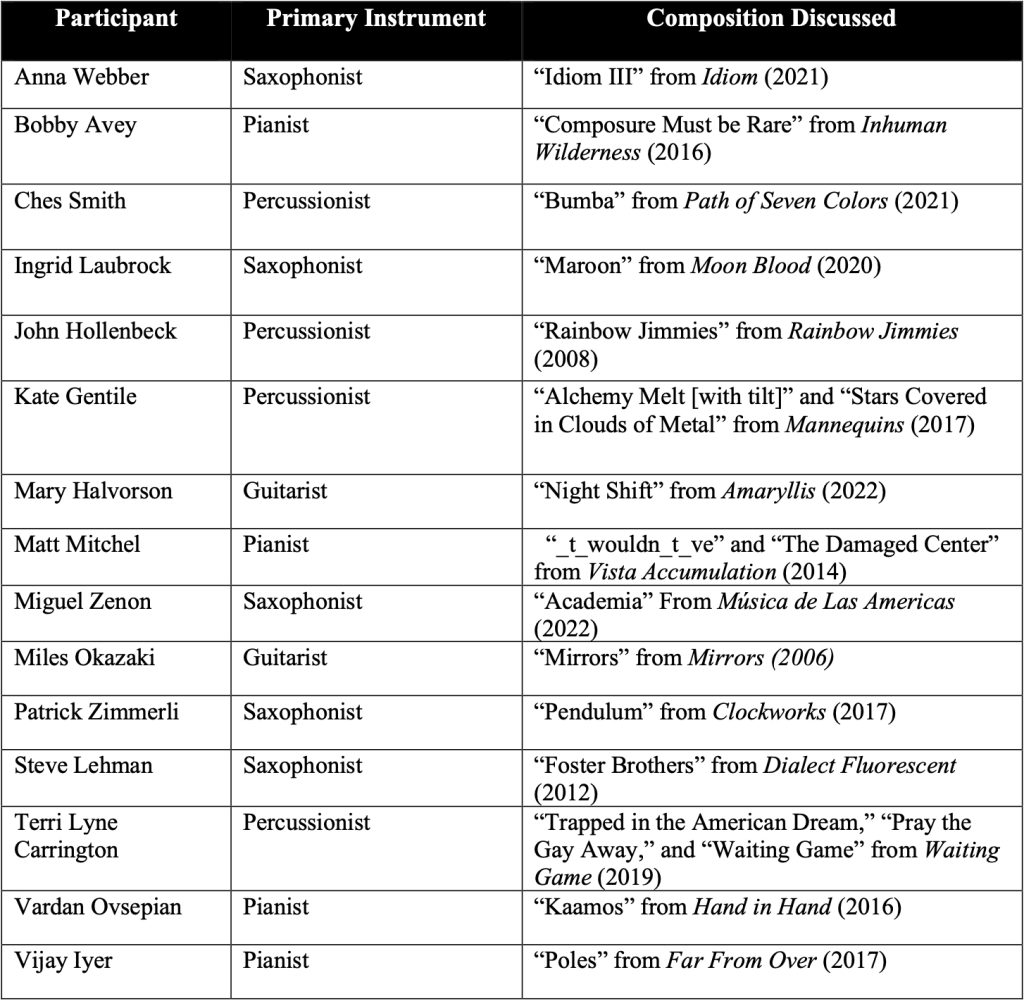

Figure 3 provides a list of the participants, their primary instruments, and—to provide a sample of their music—a composition of theirs we discussed. Unless otherwise specified, all the information and quotes attributed to the musicians come directly from the interviews. The following discussion and analysis represent my interpretation of a metric framework closely aligned with the perspectives of the musicians I interviewed. I don’t propose to speak for the musicians, nor do I argue there is a correct way professional musicians approach rhythm and meter. Instead, I use my own experience as a jazz musician to propose an analytical framework built upon the metric experience of the practitioner, and I contextualize my views with an ethnography that catalogues important modes of thinking and knowledge in jazz.

Figure 3: List of participants in the ethnographic study.

Many themes emerged from my conversations, but the most profound was the depth of rhythmic and metric practice.19Berliner (1994) and Monson (1996) also discuss the importance of rhythmic training. All participants train poly-pulse ratios, non-isochronous rhythmic superimposition, and precise synchronization of various subdivisions against a pulse. Media 3 shows Kate Gentile describing an integrated routine that involves both composition and improvisation. This approach prepares her for a typical musical situation in contemporary jazz involving sight-reading, improvising, and composing with complex rhythmic material. In Media 4, Miles Okazaki discusses why rhythmic fluidity is so important in the music he plays. How this expertise is trained in the practice room varied from musician to musician. Nonetheless, similar themes emerged. Many musicians stressed the importance of working with a metronome. Percussionist John Hollenbeck discussed his “quarter note exercise,” in which he subdivides a metronome pulse as slow as 20 beats-per-minute (bpm) into nine isochronous beats. He lands the metronome on the fifth subdivision to serve as an off-beat syncopation to the cycle.

Media 3: Kate Gentile describing rhythmic training.

Media 4: Miles Okazaki describing the importance of rhythmic fluidity.

Anna Webber, Patrick Zimmerli, Miguel Zenon, and Kate Gentile all mentioned subdividing a metronome pulse below 40 bpm using ratios, such as 5:1, 7:1, and 9:1. These subdivisions serve as tuplets to improvise with over various meters, such as 4/4 and 3/4. Complex poly-pulse ratios are also part of a consistent rhythmic practice. Kate Gentile discussed working on “anything against anything up to eleven,” referring to any integer against any other to create a ratio. While ratios, such as 1:2, 2:3, and 1:3 are rhythmic prototypes seen across many cultures, the jazz musicians I spoke to memorize and learn to improvise with more uncommon ratios, such as 5:3, 7:3, and 7:5.20See Polak et al. (2018) for a discussion of rhythmic prototypes.

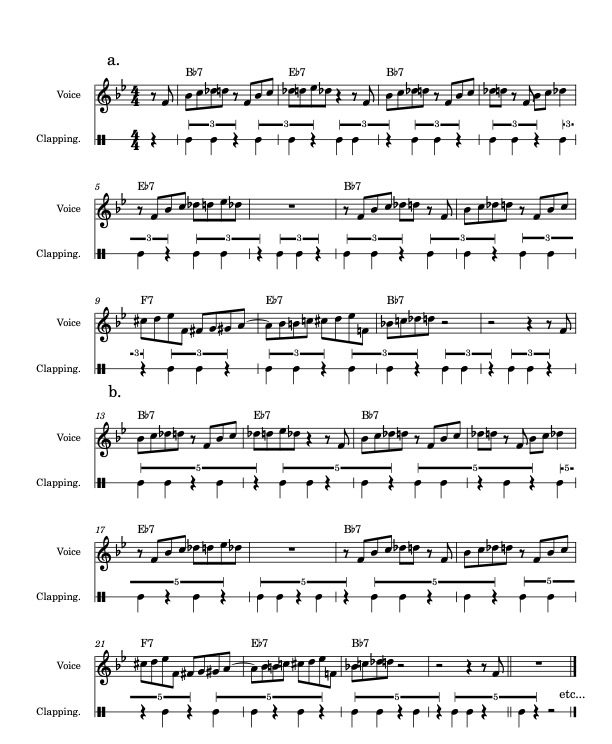

Along with technical and precision-driven rhythmic synchronization, ratios, and metronome work, every musician discussed superimposing (most often non-isochronous) rhythms over standard forms in the jazz repertoire. The meter is almost always duple or triple, and the superimposed rhythms are specifically designed to conflict with the underlying metric frame, thus generating significant metric dissonance. Percussionist Ches Smith described his practice sessions as “displacing things within the context of standard forms […] having these rehearsals for hours just playing on forms.”21Several musicians credit the recordings of Miles Davis, in a particular Live at the Plugged Nickel (1965), as inspiration for exploring rhythmic superimposition in standard forms. Waters (2011) Michaelsen (2019) discuss metric modulation and metric dissonance in the music of Miles Davis’s Second Great Quintet. Miles Okazaki described the training as “can you do this against that?” and demonstrated an increasingly layered process of superimposition involving singing the 12-bar blues “Straight No Chaser” by Thelonious Monk (Media 5). Figure 4 provides a transcription of Okazaki’s demonstration. In the first chorus, Okazaki claps a short-long ternary figure against the duple frame. In the second repetition, the ternary rhythm transforms to a non-isochronous grouping of five. This practice is part of a routine in which he plays three different rhythms simultaneously—one sung, one tapped with his foot, and another clapped.

Media 5: Miles Okazaki’s demonstration of rhythmic training over the 12-bar blues “Straight No Chaser.”

Figure 4: Transcription of Miles Okazaki’s singing and clapping of “Straight No Chaser.”

Similarly, pianist Vardan Ovsepian has worked on incongruous groupings for hand independence studies and improvisation over forms. Media 6 shows Ovsepian playing an ostinato in five with his left hand while improvising rhythmic groupings of seven and nine with his right hand. In each demonstration, Ovsepian plays four- or eight-measure phrases, highlighting the deeply embedded hypermetrical scheme endemic to jazz. Figure 5 shows a transcription of Ovsepian’s playing.

Media 6: Vardan Ovsepian’s demonstration of rhythmic training involving improvising with different rhythmic groupings over an ostinato.

Figure 5: Transcription of Vardan Ovsepian’s improvisation.

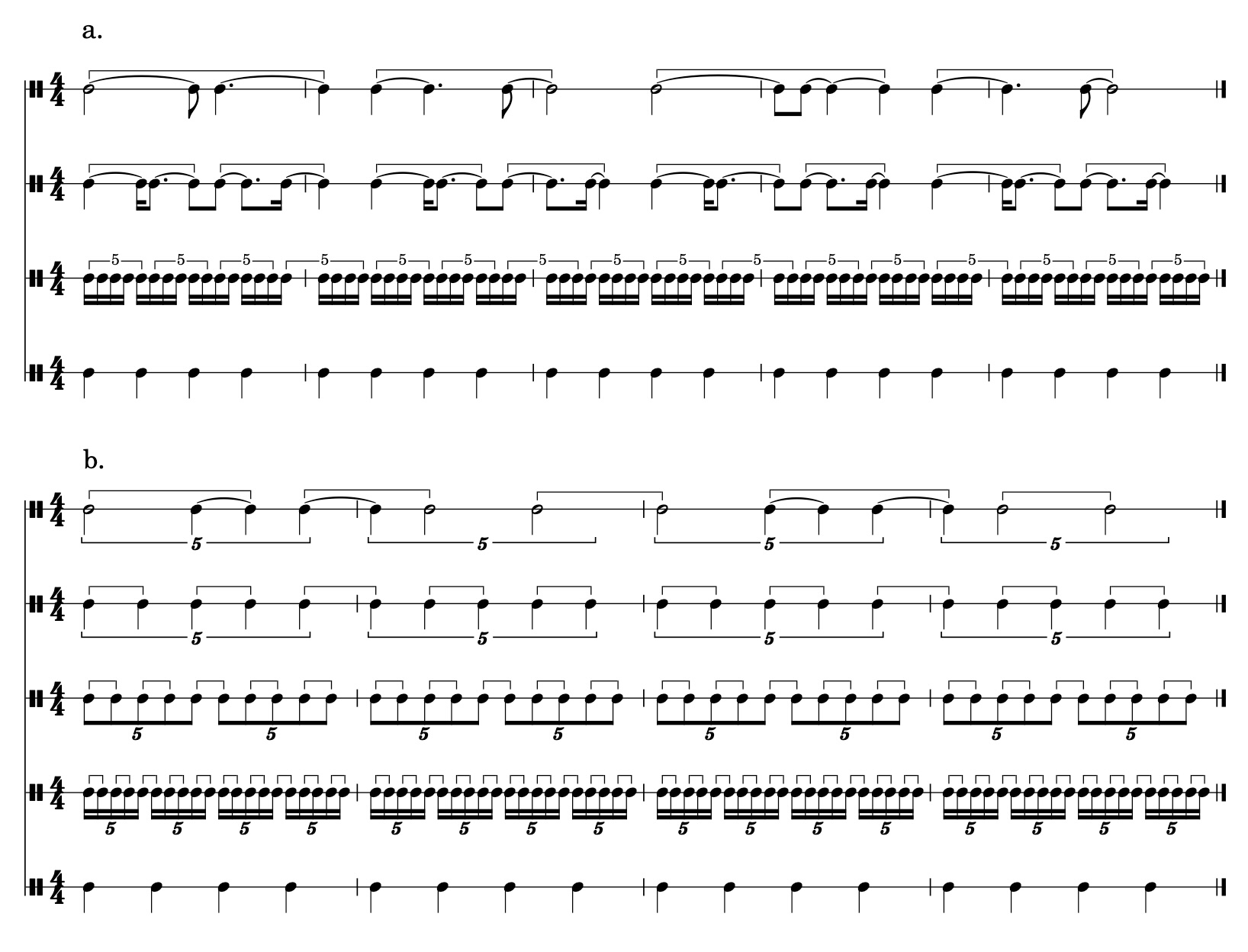

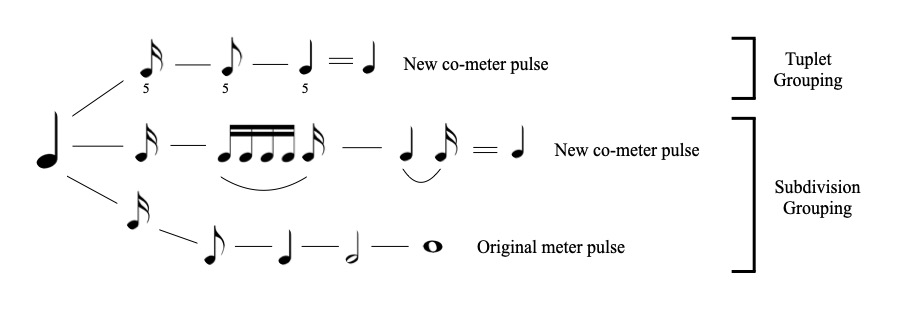

Years of practicing, improvising, and composing with these concepts lead to a dynamic and flexible approach to meter. Just as chords can be transposed, voiced differently, altered with non-chord tones, and substituted, musicians can transform a rhythm, a pulse, a set of pulses, and a meter. Figure 6 shows an illustration of the kind of metric fluidity that emerges from this training. This figure is by no means exhaustive—there are many other approaches to superimposition—but it demonstrates a common process in jazz that integrates a schematic meter with a grouping structure, leading to alternative metric states. Musicians can generate alternative pulse streams through two different grouping processes: one involves grouping the subdivisions of an underlying meter in incongruous groups; the other involves substituting the subdivision with an evenly grouped tuplet. I have chosen to illustrate groupings of five against 4/4, but this technique applies to all incongruous meters and groupings (e.g. 3/4 and groupings of five, or 7/4 and groupings of three, etc.).

Figure 6: Metric modulation techniques involving tuplet and subdivision grouping schemes for generating co-meters and co-pulses.

Figure 6a shows the subdivision grouping scheme. The sixteenth-note subdivision is grouped in sets of five, leading to a new pulse that is a sixteenth note longer than that of the underlying 4/4 pulse. This pulse can be grouped with its own constitutive set of hierarchies and subsequently felt as a new quarter note pulse in a 4/4 meter slightly slower than the original (a technique commonly known as metric modulation). Figure 6b illustrates the tuplet grouping scheme. In this case, the sixteenth note is replaced with a quintuplet that is grouped evenly to create a new metric hierarchy. The quintuplet quarter note can then be felt as the pulse in an alternative 4/4 meter slightly faster than the original.22Pulse streams might not be entrainable if the tempo falls outside of the millisecond ranges for beat perception and metricization (London 2012, p. 46). The keen reader will notice this is a different way of arriving at poly-pulse ratio training because the underlying meter sounded against the different quintuple streams creates ratios of 5:1, 5:2, and 5:4 against the underlying meter. Musicians who have devoted significant time training these techniques, such as drummers Dan Weiss and Ari Hoenig, are able to tap into these different pulse streams and meters. Media 7 shows Vardan Ovsepian recounting a story of playing with Weiss using precisely the tuplet grouping approach in Figure 6b to enter an alternative metric state.23Unlike Figure 6, which presents metric modulations that create a co-meter whose tempo is faster, Ovsepian uses the same process to describe a modulation that leads to a slower co-meter.

Media 7: Vardan Ovsepian describing metric modulation techniques while performing with drummer Dan Weiss.

How an expert jazz musician approaches the meter of a given piece is thus mediated by a wealth of prior performance experience and training. As demonstrated by Ovsepian, whose understanding of the techniques Weiss experimented with improved over time, the material experienced from those contexts can be abstracted, refined, and made accessible for future musical situations. In the context of improvised music, the meter of a piece as outlined by a score belies a deeper and more dynamic system used by practitioners that includes an integrated network of alternative co-pulses and co-meters. Figure 7 demonstrates a possible network of pulse streams emergent because of a shared initial pulse. I do not propose that all jazz musicians are capable of this. But increased training and experience through listening or performing with these concepts—which are fundamental to jazz and Afro-diasporic music—allows us to endogenously maintain an underlying pulse or meter against highly conflicting acoustic signals.24Pressing (2002) theorizes complex rhythmic interactions in Afro-diasporic music, such as cross-rhythms, syncopation, and polyrhythm, are a form of “perceptual rivalry” that compete for a listener’s metric entrainment. The ensuing play between a referent, such as a formal structure, and a rhythm represents both a broader form of expression in Black diasporic cultures and a distinct characteristic of groove-based music.

Figure 7: Integrated network of possible pulse streams.

Dynamic Meter in Action

A dynamic and flexible approach to meter in improvised music not only involves co-pulses and co-meters with constitutive hierarchies, but also rhythms as distinct entities capable of serving the structural role of meter. Figure 8 and Media 8 present an excerpt of Patrick Zimmerli’s “Pendulum.”25See Zimmerli (2018) for complete audio track, available through this link. The B section has a triplet ostinato played by the bass and piano.26I’ve omitted the piano in the figure for ease of reading. This figure can be segmented in groups of seven eighth-note triplets to form a non-isochronous 1 + 2 + 2 + 2 rhythm, a variant of the common 2 + 2 + 3. This grouping scheme creates a cycle of eight groupings of seven with an extra quarter note at the end. To further complicate metric interpretations, the starting point of the ostinato is uncertain. The first onset can be felt in three different ways: 1) as a potential downbeat, 2) as a syncopated after-beat accent where the first rest is the downbeat, and 3) as an anacrusis to the third eighth-note triplet, another potential downbeat. The melody uses a sixteenth-note subdivision that segments phrases in groups of ten due to the parallel melodic and rhythmic structure. The initial phrase follows a 2 + 3 + 2 + 3 grouping from C#5 to F5, which becomes clear in the saxophone’s articulation. As a result of these varying subdivision levels, there are multiple pulse streams generating grouping dissonances against the steady quarter note pulse. To complicate matters even further, Zimmerli cheekily remarked that “by the way […] Pendulum is in 4/4.” Because the melody is grouped in fives, it would be much more challenging to sight-read the music if written in 4/4, as the five groupings neatly fit inside the five-beat measures. While the notated meter provides a simpler shorthand for reading the music, it does not necessarily serve as the only organizational scheme for performing and improvising.

Figure 8: Zimmerli’s “Pendulum,” mm. 1-4 of the B section; brackets of 7 and 10 added by author.

Media 8: Audio excerpt of the B section of “Pendulum.” Listen to Media 8.

When I asked the musicians how they interpreted “Pendulum,” many disregarded the 5/4 meter. Bobby Avey said, “I don’t feel a strong gravity from the meter per se. I feel more that there’s a quarter note pulse from the drums, you have this triplet figure on top of it, and it just happens to be x amount of beats.” Miguel Zenon said “I wasn’t thinking about 5/4. […] I’m thinking about what the pulse to subdivision relationship is so I can understand where that falls and play with that.” Similarly, Miles Okazaki said “I don’t think about 5/4. I’m thinking about rhythmic shapes. I’ve done a lot of work practicing rhythmic shapes in different subdivisions of the beat. If you give me this rhythm and tell me to play it in triplets, that’s going to be OK.”27Okazaki explores the visualization of rhythm and pitch into different shapes through his work Fundamentals of Guitar (2015) and 351 Shapes (2022).

Instead of using the 5/4 meter, the musicians chose to orient themselves by focusing on the pulse and its unique relationship to the non-isochronous ostinato rhythm. This echoes many studies and ethnographies of Afro-Cuban, Afro-Diasporic, and African music that exhibit timeline rhythms, also known as claves.28See Agawu (2003), Locke (2011) Stover (2009 and 2019), and Benadon (2020) for discussions of timeline rhythms While there is still debate as to whether timeline rhythms supplant the need for meter or whether they function as meter, I follow Benadon (2020) who proposes that “musicians employ the referential markers offered by both meter and timeline to structure their rhythmic phrasing” (p. 1). This view allows for the possibility that both meter and rhythm serve as structural entities to temporally follow music. Given the important influence of European, West African, and Afro-Diasporic music on the development of jazz, it is not surprising that the metric spaces in jazz afford musicians and listeners the ability to metrically engage with both a hierarchical meter common to Western European music and a reference structure, like a timeline, common to African and Afro-diasporic music. If meter is a mental capacity to temporally organize music into discrete, repeating, and hierarchical structures, I argue that metricization can involve any durational musical entity—such as a pulse, a set of pulses, or a rhythm—to serve as a referential structure in that cognitive process. For many jazz musicians, the non-isochronous rhythm and its accentual interaction with the pulse assumes the role of meter in “Pendulum.”

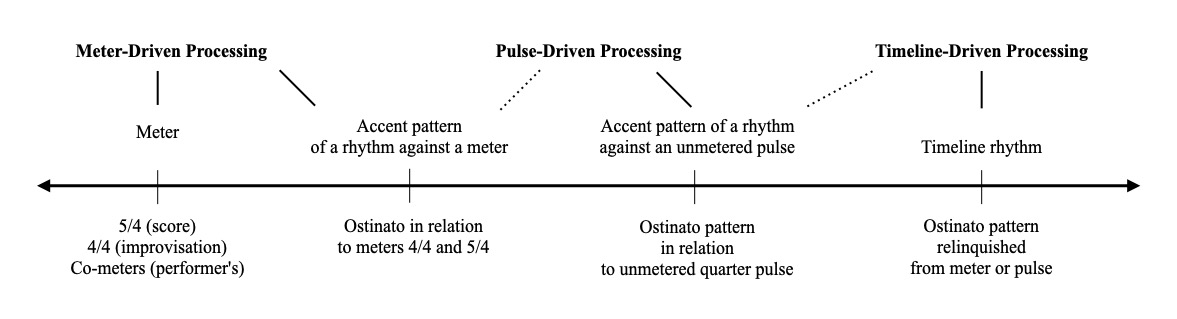

Thus, alongside the notated meter (5/4) and the alternative meter for improvisation (4/4), the timeline rhythm of the ostinato provides yet another framework to temporally structure and follow “Pendulum.” My conversations with expert practitioners demonstrate that, when they assess a piece, they rely on a series of prior metrical experiences that can manifest in possible co-pulses and co-meters. These prior metrical experiences are coupled with the metric affordances already present in the music and allow practitioners to traverse a much wider spectrum of metric possibilities than those highlighted by a score. From this, we can propose a dynamic, flexible, context-specific, and individualized metric process for “Pendulum” that inhabits a spectrum of entrainment possibilities.

Figure 9: Spectrum of meter-, pulse-, or timeline-driven possibilities for entrainment in “Pendulum.”

Figure 9 above highlights a possible spectrum of entrainment with four metric states. On the left side are schematic meters. These are metric spaces with beat hierarchies and hypermetric schemes. The 5/4 meter for reading, 4/4 meter for improvisation, and a series of co-meters emergent from a shared initial pulse serve as meter-driven forms of temporal processing. As we continue towards the right, the ostinato’s non-isochronous timeline rhythm (1 + 2 + 2 + 2 and other variants of 2 + 2 + 3) begins to assume more structural responsibility. The second metric state combines meter and timeline into one structural framework. The superimposition of the timeline against the meter generates an accent pattern that can be learned and felt. The entrainment of meter as a series of alternating strong and weak isochronous pulses is transformed into a schematic frame contingent on where the onsets of the ostinato land, on or off the beat, for each measure. Instead of following metric accents, musicians can follow the measures’ unique set of accents that support a meter- or timeline-oriented hearing while still tracking the downbeat of each measure.

As we continue traversing the entrainment spectrum, meter becomes less relevant, and the resulting states generate accents and structural placements in the music quite different from those of meter. The third metric state combines the ostinato’s timeline rhythm with an unmetered pulse as the structural frame. This allows for organizing the ostinato as eight repetitions of the timeline rhythm with an extra quarter note at the end.29Several musicians in the interviews described memorizing the ostinato using this thought process. The last state represents unmetered timeline rhythms without underlying pulses. The 1 + 2 + 2 + 2 ostinato rhythm in triplets or the 3 + 2 rhythm of the melody in sixteenth notes can be referents freed from a figure/ground relationship where the ground represents a pulse or a meter.

Figure 10: Entrainment of the “Pendulum” ostinato involving the accent patterns of both meter and timeline rhythms. Accents indicate metrically strong beats, and accents in parenthesis highlight strong beats weakened by the ostinato’s off-beat placement. Star symbols indicate metrically strong beats that coincide with timeline accents, and bullseye symbols indicate metrically weak beats that coincide with timeline accents.

Figure 10a provides a series of possible metrically salient accents that combine a 4/4 meter and the superimposed timeline (metric state 2 in Figure 9).30I use 4/4 instead of the notated 5/4 meter because Zimmerli states the piece can also be performed in 4/4. Regular accent symbols indicate common metric positions. Accents in parentheses are strong metric beats that can be a part of the accent pattern but, because the ostinato is an off-beat syncopation, that accent is challenging to hear strongly. Star symbols indicate metrically strong beats that coincide with a timeline accent, and bullseye symbols designate timeline accents that land on a beat that is not strong metrically but can nonetheless serve as a salient structural point. Figure 10b demonstrates my hearing of the form using this metric state. In many instances, only one accent is needed for a given measure to maintain my place in the form. While the resulting temporal scheme may seem haphazard in its construction, it allows for a flexible approach that supports both meter- and timeline-oriented acoustic signals.

In sum, three overarching forms of temporal processing emerge from the entrainment spectrum. The first is driven by traditional notions of meter. This process is comprised of a recurring alternating pattern of strong and weak isochronous pulses, constitutive beat hierarchies, and hypermetric phrase structures. The second is driven by a pulse-to-subdivision relationship. A distinct accent pattern generated from the juxtaposition of a rhythm against a pulse can be learned, manipulated, and improvised with. The last state is predicated on timeline rhythms. This state can exist without meter or pulse as a structural backdrop and provide relevant reference points—distinct from meter—to follow the music. This spectrum, while admittedly reductive, provides a more representative picture of the multidimensional ways that the musicians I spoke to structure music. Musicians can traverse the spectrum to suit their needs for a given musical situation and switch seamlessly from one side to the other.

Cultural Insiders and Unsounded Referents

The ethnographic findings described above demonstrate how expert jazz musicians temporally structure music in flexible and context-specific ways. Years of training and performance generate a deep repository of prior metrical experiences that become internalized reference structures and can be reused in new musical situations. This view echoes a growing body of literature supporting qualitative and perceptual differences in interpretations of music because of enculturation. While enculturation is currently debated in music psychology, an increasing number of studies empirically support its impact in rhythm perception.31 See Polak et al. (2020), Danielsen et al. (2021) and Jacoby et al. (2023). Several music scholars have also found culturally unique rhythmic and metric practices. Haugen (2021) describes the consistent endogenous reference structures used by cultural insiders in Norwegian Telespringar as “intended meters.” While Telespringar affords multiple metric interpretations, the music is “experienced within a consistent metrical context by insiders” (2021, p. 23). Haugen follows Clayton (2013) who describes “culture-specific meters” emerging from “patterns that have been learned and internalized over a long period of time […] in use within a particular society over many generations” (2013, p. 32). I follow Haugen and Clayton in expanding traditional definitions of meter to account for any endogenous temporal organization of music. These can be structures akin to what Miles Okazaki called “rhythmic shapes,” Kate Gentile called “scaffolds,” or pianist Matt Mitchell referred to as “a relationship with pulse and with groove that is sustaining over long periods of time.” Although each musician’s description is unique, they all allude to the practiced skill of internalizing and improvising highly sophisticated rhythmic material against an underlying referent, such as a pulse or a set of pulses.

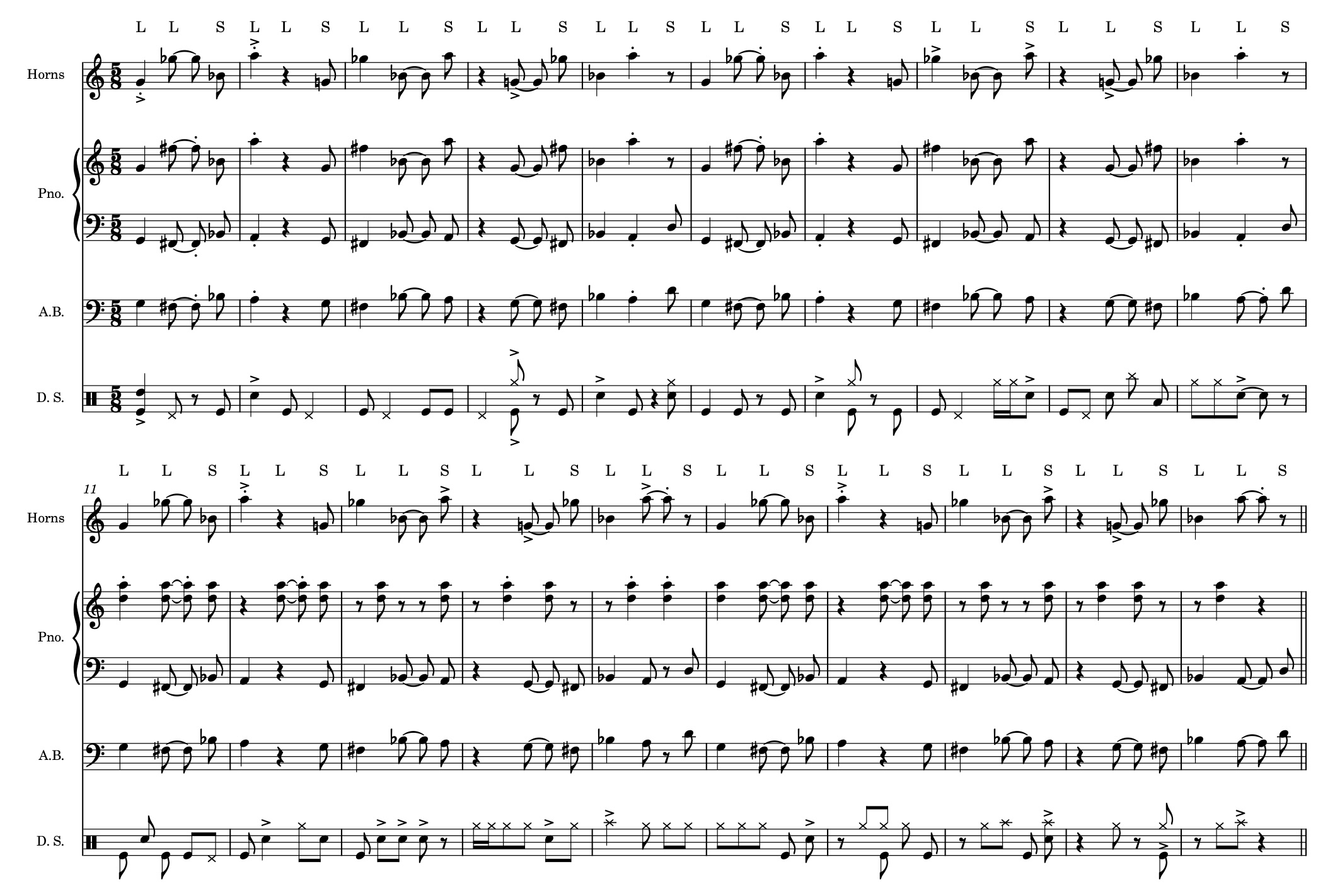

Figure 11: Excerpt of the A section of “Poles.”

Media 9: Audio excerpt of the A section of “Poles.” Listen to Media 9.

Figure 11 and Media 9 present the A section of Vijay Iyer’s “Poles” from Far from Over (2017).32See Iyer (2017) for the complete audio track, available through this link The quintuple-based meter established by the piano ostinato and drums is quickly destabilized by three groupings of seven broken into 2 + 2 + 3 and one grouping of four broken into 2 + 2. Although the melodic surface could indicate three measures of seven and one measure of four, Iyer superimposes these rhythms just like Hamasyan and Zimmerli did in “New Maps” and “Pendulum,” respectively. Iyer described the A section of “Poles” as “three [groupings of] sevens and one [grouping of] four across fives […] [the piece’s rhythmic organization is] both about the pulse and a cross rhythm,” alluding to the timeline pattern of seven and four and its interaction with the stable meter. Determining a pulse is tricky, however. While the pulse could be the eighth note subdivision or a non-isochronous pulse of 2 + 3, the brisk tempo also allows the downbeat of every 5/8 measure to serve as a pulse. When applying the grouping technique from Figure 6a, we can also generate an isochronous pulse at the quarter note and half-note level that spans two or four measures of 5/8 and frequently aligns with the ostinato rhythm (Figure 12). These pulse layers are flexible in their ability to represent a hypermetric variant of the 5/8 meter and form part of a beat hierarchy with the timeline pattern.

Figure 12: Pulse layers in the A section of “Poles.”

The B section of “Poles” (Figure 13) is even more unclear. The 5/8 groove is completely abandoned, the groupings are no longer based on seven, and the meter appears to have changed because the drums follow melodic accents. It is in this very moment that a previously entrained metric state is most likely to collapse, and thus that culture-specific and intended meters emerge. Despite an entirely conflicting acoustic signal, the B section maintains the 5/8 meter and the pulses demonstrated in Figure 12 act as an unsounded grounding figure against the new melodic sequence, as we shall see below.33Agawu (2003) remarks that “the morphology of a topos [short timeline rhythm] should never be divorced from its main beats and referential cycle. If you ignore the role of the unsounded […] you might then be led to think that the first sound you hear marks the beginning of a metrical cycle, that relatively longer durations indicate downbeats, or that downbeats must be ‘filled’ with sound rather than silence” (p. 77).

Figure 13: Excerpt of the B section of “Poles.” The letter-symbols “S” and “L” above the staff indicate short and long rhythms of 1 and 2 eighth notes.

Media 10: Audio excerpt of the B section of “Poles.” Listen to Media 10.

The endogenous maintenance of an unarticulated referent—a fundamental characteristic of African and Afro-diasporic music—allows us to disambiguate the B section of “Poles.” While Iyer corroborated my transcription, he also revealed an underlying organizational structure exceptionally difficult to uncover without his input. A melodic sequence of four notes and a quarter-note rest (G – F# – Bb – A – Rest) is continually repeated throughout the B section. This five-point sequence is cycled against a long—long—short sequence repeated rhythmically as 2 + 2 + 1. The pitch sequence cycles six times against the measure—the duration sequence—for a total of ten measures. After the pitch and duration cycles realign, the piano shifts to articulate the previous grouping of the A section, 7 + 7 + 7 + 4, which is superimposed against the rotating scheme (G – F# – Bb – A – Rest). Amazingly, Iyer performed this section with two different underlying pulses. While singing the melodic sequence, he clapped the downbeats of each 5/8 measure and then shifted to clap the quarter note pulse expressed by the 7 + 7 + 7 + 4 cycle, showing an exceptional level of fluency switching between two conflicting pulse streams while maintaining the already complicated melodic sequence.

Iyer is compartmentalizing the music with patterns and pulses that are frequently not articulated or significantly obscured within the music, able to seamlessly move from one side of the spectrum to the other. The resultant temporal gestalt of “Poles” combines asymmetrical meters and superimposed timeline patterns that allow for various entrainment schemes. Many of these schemes demand experience with metrically dissonant spaces that exhibit significant degrees of syncopation, cross-rhythms, and displacement. When presented with such conflicting perceptual signals, a culture-specific approach does not immediately signal metric change but instead engages in a centuries-old African and Afro-diasporic tradition of maintaining an often-unsounded reference structure—whether a pulse, a meter, or a rhythm—amidst a dialogic network of rhythmic counterpoint specifically designed to produce perceptual rivalry.34On the possible culture-specific differences between European and African music practices, Temperley (2000) speculates that a listener approaches new music through the metric contexts of the music they are accustomed to: “the Western perception involves shifting the metrical structure in order to better match the phenomenal accents, while the African perception favors maintaining a regular structure even if it means a high degree of syncopation.” (p. 79)

Conclusion

Throughout this essay, I presented recent jazz compositions that exhibit significant levels of metric dissonance. The superimposition of rhythms that conflict with an underlying meter creates series of pulse layers that result in polymeter, displacement, and syncopation. Historically, these devices appeared through the juxtaposition of an improvised solo against a standard tune. The explicit separation between metric and grouping structure of previous jazz repertoires created a clear metric context that listeners could easily maintain to disambiguate the metric dissonance. However, the techniques previously employed by soloists have now become part of compositional structures. The pieces analyzed in this essay establish metric multivalence as a central compositional characteristic that affords listeners various metric orientations, often leading to vastly different approaches to structure and groove. I demonstrate how, despite an increase in conflicting acoustic signals suggestive of mixed meter structures, stable and unchanging metric frames continue to appear in contemporary jazz repertoire.

I have presented an analytical framework that aligns with the way experienced musicians metrically process their music, and I contextualized my analysis with an ethnographic study involving professional jazz musicians. My interviews revealed consistent approaches and knowledge that appear foundational for unearthing the culture-specific meters hidden within conflicting pulse streams in contemporary jazz. The rhythmic sophistication exhibited by these musicians reveals an intricate form of entrainment, a kind of metric lattice predicated not just on meter, but also on a pulse-to-subdivision relationship that is adaptable, fluid, and designed to navigate increasingly complex metric spaces. This form of entrainment is built on a deep and sophisticated network of prior metric experiences refined through years of practice and performance in an increasingly globalized musical culture. Because of the dual influences of European and African music, experienced jazz performers develop a metric and rhythmic vocabulary conversant with both the stable metric frames and hypermetric structures of meter in Western music, as well as the highly syncopated and intricate referential structures of timeline musics common to African and Afro-diasporic cultures. Pieces, such as Iyer’s “Poles” and Zimmerli’s “Pendulum” enable performers and listeners to traverse an entrainment continuum where both meter and timeline patterns provide structurally unique paths for temporally organizing the music.

I chose to follow a hybrid methodology involving ethnography and analysis to achieve two goals: 1) to incorporate the often-missing voice of expert practitioners into academic discussions of their music, and 2) to present an ecologically valid analysis that connects scholarship with jazz performance practice. While not the explicit purpose of this study, I believe the findings of my ethnographic study contribute to recent scholarship that challenges theoretical and cognitive principles underlying conventional definitions of meter in Western music.35See Clayton (2020), Benadon (2020), Polak et al (2016 and 2020). Meter, defined as an abstract theoretical model, is not always representative of meter as a dynamic cognitive skill employed by listeners and performers. This essay could present evidence to support discussions of context- and genre-specific models of meter, as well as cross-cultural research in music cognition involving experienced improvising musicians. Many of the musicians I interviewed referenced a variety of influences, including Western art music, Brazilian, Balkan, Indian, West African, and popular musics, like metal. While I primarily focused on a theoretical discussion of meter by examining the complex relationship between pulses, timelines, and rhythms as metrically viable entities, future research could explore a historiographic framework that identifies parallels between rhythmic complexity in jazz and other styles.

The pieces I discussed are part of a repertoire that is just now capturing the attention of scholars in music theory. Continued study of this music, and the culture-specific meters used by practitioners, could reveal novel ways of understanding intricate temporal structures and further connect analytical discourse to performance practice.

Acknowledgements

I’m deeply thankful to Daphne Leong, Keith Waters, Brian Levy, and John Gunther for their tremendous encouragement and guidance. Daphne’s incisive feedback fundamentally influenced the scope and direction of this project. And my sincerest thanks to the Thompson Jazz Studies Department at the University of Colorado Boulder for funding the ethnographic study.

Bibliography

Agawu, Kofi (2014), Representing African Music. Postcolonial Notes, Queries, Positions, New York, Routledge.

Benadon, Fernando (2020), “Meter Isn’t Everything. The Case of a Timeline-Oriented Cuban Polyrhythm,” New Ideas in Psychology, vol. 56, article 100735.

Berliner, Paul (1994), Thinking in Jazz. The Infinite Art of Improvisation, Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Biamonte, Nicole (2014), “Formal Functions of Metric Dissonance in Rock Music,” Music Theory Online, vol. 20, no 2, https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.20.2.3

Boyle, Antares (2021), “Flexible Ostinati, Groove, and Formal Process in Craig Taborn’s Avenging Angel,” Music Theory Online, vol. 27, no 2, https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.27.2.3

Butler, Mark J. (2006), Unlocking the Groove. Rhythm, Meter, and Musical Design in Electronic Dance Music, Bloomington, Indiana University Press.

Clayton, Martin (2013), “Entrainment, Ethnography and Musical Interaction,” in Martin Clayton, Byron Dueck, and Laura Leante (eds.), Experience and Meaning in Music Performance, Oxford University Press.

——— (2020), “Theory and Practice of Long-Form Non-Isochronous Meters. The Case of the North Indian Rūpak Tāl,” Music Theory Online, vol. 26, no 1, https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.26.1.3

Cohn, Richard (2001), “Complex Hemiolas, Ski-Hill Graphs and Metric Spaces,” Music Analysis, vol. 20, no 3, pp. 295–326.

——— (2020), “Meter,” in Alexander Rehding and Steven Rings (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Critical Concepts in Music Theory, Oxford University Press.

Danielsen, Anne et al. (2022), “Sounds Familiar(?). Expertise with Specific Musical Genres Modulates Timing Perception and Micro-Level Synchronization to Auditory Stimuli,” Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, vol. 84, no 2, pp. 599–615.

Downs, Clive (2000), “Metric Displacement in the Improvisation of Charlie Christian,” in Edward Berger, Henry Martin, and Dan Morgenstern (eds.), Annual Review of Jazz Studies. 1, 2000–2001, Lanham, Scarecrow Press, pp. 39–68.

Folio, Cynthia (1995), “An Analysis of Polyrhythm in Selected Improvised Jazz Solos,” in Elizabeth West Marvin and Richard Hermann (eds.), Concert Music, Rock, and Jazz Since 1945. Essays and Analytical Studies, Rochester, University of Rochester Press, pp. 103–134.

Hamasyan, Tigran (2020), “New Maps,” YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8PsxXsr97HA, accessed 25 November 2014.

Hannaford, Marc (2017), “Subjective (Re)Positioning in Musical Improvisation. Analyzing the Work of Five Female Improvisers,” Music Theory Online, vol. 23, no 2.

Hasty, Christopher (1997), Meter as Rhythm, New York, Oxford University Press.

Haugen, Mari (2021), “Investigating Music-Dance Relationships,” Journal of Music Theory, vol. 65, no 1, pp. 17–38.

Imbrie, Andrew (1973), “Extra Measures and Metrical Ambiguity in Beethoven,” in Alan Tyson (ed.), Beethoven Studies, New York, W.W. Norton, pp. 45–66.

Iyer, Vijay (2018), “Poles,” performed by the Vijay Iyer Sextet, ECM Records, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KhoH4jzrtoM, accessed November 25 2025.

Jacoby, Nori et al. (2020), “Cross-Cultural Work in Music Cognition. Challenges, Insights, and Recommendations,” Music Perception, vol. 37, no 3, pp. 185–195.

Jacoby, Nori et al. (2024), “Commonality and Variation in Mental Representations of Music Revealed by a Cross-Cultural Comparison of Rhythm Priors in 15 Countries,” Nature Human Behaviour, vol. 8, no 5, pp. 846–877.

Krebs, Harald (1999), Fantasy Pieces. Metrical Dissonance in the Music of Robert Schumann, New York, Oxford University Press.

Large, Edward W., and Joel S. Snyder (2009), “Pulse and Meter as Neural Resonance,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 1169, no 1, pp. 46–57.

Larson, Steve (2005), “Rhythmic Displacement in the Music of Bill Evans,” in Structure and Meaning in Tonal Music. Festschrift for Carl Schachter, Hillsdale, New York, Pendragon Press.

Leong, Daphne (2007), “Humperdinck and Wagner. Metric States, Symmetries, and Systems,” Journal of Music Theory, vol. 51, no 2, pp. 211–243.

——— (2011), “Generalizing Syncopation. Contour, Duration, and Weight.” Theory and Practice, vol. 36, pp. 111–150.

Lerdahl, Fred, and Ray S. Jackendoff ([1983]1996), A Generative Theory of Tonal Music, Cambridge, The MIT Press.

Locke, David (2011), “The Metric Matrix. Simultaneous Multidimensionality in African Music,” Analytical Approaches to World Music, vol. 1, no 2, pp. 48–72.

London, Justin (2012), Hearing in Time. Psychological Aspects of Musical Meter, New York, Oxford University Press.

Love, Stefan (2012), On Phrase Rhythm in Jazz, Ph.D. diss., University of Rochester.

——— (2013), “Subliminal Dissonance or ‘Consonance’? Two Views of Jazz Meter,” Music Theory Spectrum, vol. 35, no 1, pp. 48–61.

Lucas, Olivia (2018), “‘So Complete in Beautiful Deformity’. Unexpected Beginnings and Rotated Riffs in Meshuggah’s obZen,” Music Theory Online, vol. 24, no 3.

Michaelsen, Garrett (2019), “Making ‘Anti-Music’. Divergent Interactional Strategies in the Miles Davis Quintet’s The Complete Live at the Plugged Nickel 1965,” Music Theory Online, vol. 25, no 3, https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.25.3.4

——— (2023), “Projection, Call-Response and the Improvisational Moment,” Music Analysis, vol. 42, no 2, pp. 269–275.

Mirka, Danuta (2009), Metric Manipulations in Haydn and Mozart. Chamber Music for Strings. 1787-1791, Oxford / New York, Oxford University Press.

Monson, Ingrid (1997), Saying Something. Jazz Improvisation and Interaction, Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Murphy, Scott (2007), “On Metre in the Rondo of Brahms’s Op. 25,” Music Analysis, vol. 26, no 3, pp. 323–353.

Okazaki, Miles (2015), Fundamentals of Guitar. A Workbook for Beginning, Intermediate, or Advanced Students, Pacific, Mel Bay.

Pieslak, Jonathan (2007), “Re-Casting Metal. Rhythm and Meter in the Music of Meshuggah,” Music Theory Spectrum, vol. 29, no 2, pp. 219–245.

Polak, Rainer et al. (2018), “Rhythmic Prototypes across Cultures. A Comparative Study of Tapping Synchronization,” Music Perception vol. 36, no 1, pp. 1–23.

Porter, Eric (2002), What Is This Thing Called Jazz? African American Musicians As Artists, Critics, and Activists, Berkeley, University of California Press.

Pressing, Jeff (1984), “Cognitive Processes in Improvisation,” in Advances in Psychology, vol. 19, pp. 345–363.

——— (2002), “Black Atlantic Rhythm. Its Computational and Transcultural Foundations,” Music Perception. An Interdisciplinary Journal, vol. 19, no 3, pp. 285–310.

Schumann, Scott C. (2021), “Asymmetrical Meter, Ostinati, and Cycles in the Music of Tigran Hamasyan,” Music Theory Online, vol. 27, no 2, https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.27.2.2

Stover, Christopher D. (2009), A Theory of Flexible Rhythmic Spaces for Diasporic African Music, Ph.D. diss., University of Washington.

——— (2019), “Contextual Theory, or Theorizing between the Discursive and the Material,” Analytical Approaches to World Musics, vol. 7, no 2, pp. 1-29.

——— (2023), “Calls and Responses,” Music Analysis, vol. 42, no 2, pp. 276–283.

Temperley, David (2000), “Meter and Grouping in African Music. A View from Music Theory,” Ethnomusicology, vol. 44, no 1, pp. 65–96.

Waters, Keith (1996), “Blurring the Barline. Metric Displacement in the Piano Solos of Herbie Hancock,” in Annual Review of Jazz Studies, vol. 8, pp. 19–37.

——— (2011), The Studio Recordings of the Miles Davis Quintet, 1965-1968, New York / Oxford, Oxford University Press.

——— (2019), Postbop Jazz in the 1960s. The Compositions of Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, and Chick Corea, New York, Oxford University Press.

Yeston, Maury (1976), The Stratification of Musical Rhythm, New Haven, Yale University Press.

Yust, Jason (2018), Organized Time. Rhythm, Tonality, and Form, New York, Oxford University Press.

Zimmerli, Patrick (2018), “Pendulum,” performed by the Patrick Zimmerli Quartet, Music Video Distributors Inc., YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jDGGygYgPx4&list=RDjD

| RMO_vol.12.2_Orco |

Attention : le logiciel Aperçu (preview) ne permet pas la lecture des fichiers sonores intégrés dans les fichiers pdf.

Citation

- Référence papier (pdf)

Andres Orco, « Meter in Contemporary Jazz. A Practitioner-Based Approach », Revue musicale OICRM, vol. 12, no 2, 2025, p. 1-26.

- Référence électronique

Andres Orco, « Meter in Contemporary Jazz. A Practitioner-Based Approach », Revue musicale OICRM, vol. 12, no 2, 2025, mis en ligne le 12 décembre 2025, https://revuemusicaleoicrm.org/rmo-vol12-n1/meter-contemporary-jazz/, consulté le…

Auteur

Andres Orco, Yale University

Andres is a PhD student in Music Theory at Yale University. He is interested in jazz, rhythm and meter, and music cognition. He has presented his research at conferences organized by the Society of Music Theory and Rhythm in Music Since 1900. Prior to Yale, Andres studied jazz guitar performance and pedagogy, completing a BM from Berklee College of Music, an MM from the New England Conservatory, and a DMA from the University of Colorado Boulder (CU). While in Colorado, Andres performed throughout the Denver metropolitan area and served as a lecturer at CU Boulder.

Notes

| ↵1 | Love (2013) refers to the schematic organization of jazz from the Great American Songbook, bebop, and hard-bop substyles. These styles account for most repertoire studied in scholarship. |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | In what follows, I present each analysis with an accompanying musical excerpt and a YouTube link with the entire piece discussed. To situate the passages with their surrounding metrical context, I highly encourage the reader to listen to the pieces in their entirety. |

| ↵3 | See Hamasyan (2020) for the complete audio track, available through this link. |

| ↵4 | Except for Patrick Zimmerli’s “Pendulum” (Figure 8), all notated figures are my own transcriptions. |

| ↵5 | Note that the last grouping of 5 starting with the Bb continues into the beginning of the ostinato. |

| ↵6 | Large-scale hypermetric structures that maintain an underlying unchanging meter in favour of local measure-to-measure metric dissonance have also been found in popular music, such as EDM, rock, and metal. See Butler (2006), Pieslak (2007), Biamonte (2014), and Lucas (2018). |

| ↵7 | I notated Figure 2 in 5/8 instead of 5/4 because the rest of the piece—the music beyond the excerpted example—can be heard and notated more clearly in 5/8. Hamasyan’s introductory statement affords many possible metric hearings, and later contextualizes it in 5/8, the main metrical context of the piece. |

| ↵8 | Ecological validity is a common term in psychological research used to describe the relationship between a study’s methodologies and conclusions—often determined in controlled lab environments—to the study’s population out in the real world. A study that can more closely generalize observed human behaviours in the real world is considered more ecologically valid. |

| ↵9 | See Folio (1995), Waters (1996), and Downs (2001). Harald Krebs’ (1999) taxonomy for metric dissonance has been widely used by jazz scholars, such as Larson (2005) and Love (2013), to differentiate between subliminal and direct displacement and grouping dissonances. |

| ↵10 | Pressing (1984) theorizes that jazz improvisation involves the interaction with and against a referent, “an underlying formal scheme or guiding image specific to a given piece” (p. 346). |

| ↵11 | Mirka (2009) and Yust (2018) build upon Hasty’s work within the context of Western art music. Stover (2009 and 2023) and Michaelsen (2023) elaborate projection theory in jazz and Afro-diasporic music through the lens of improvisation and call-and-response. |

| ↵12 | Imbrie (1973) differentiates between “conservative listeners” who preserve the previous metric context and “radical listeners” who adapt to the conflict input in favour of a new meter. |

| ↵13 | London’s (2012) Many Meters Hypothesis speculates that “metric competence resides in […]knowledge of a very large number of context-specific metric timing patterns. The number and degree of individuation among these patterns increase with age, training, and degree of musical enculturation.” (p. 182). |

| ↵14 | Hannaford (2017) analyzes the improvisational spaces of five contemporary jazz compositions by current female composers, all of which exhibit mixed meters and irregular phrase lengths. Both Schumann (2021) and Boyle (2021) discuss the structural importance of ostinati, asymmetrical meters, and metrically malleable passages. |

| ↵15 | London (2012) defines metric malleability as “a property by which melodic or rhythmic patterns may be heard in more than one metric context” (p. 99). |

| ↵16 | Cohn (2020) follows Leong (2011) who visualizes shifts from one metric orientation to another through a displacement continuum. Whether these metric states can be entrained simultaneously is outside the scope of this paper. I refer to the co-existence of metric orientations simply as an objective phenomenon of the musical surface, not as a perceptual capability of the listener or performer. |

| ↵17 | I am deeply grateful to the musicians for participating in the ethnographic study; they kindly gave me permission to use the video and interview content as part of this research. |

| ↵18 | See Berliner (1994), Monson (1996), and Porter (2002). |

| ↵19 | Berliner (1994) and Monson (1996) also discuss the importance of rhythmic training. |

| ↵20 | See Polak et al. (2018) for a discussion of rhythmic prototypes. |

| ↵21 | Several musicians credit the recordings of Miles Davis, in a particular Live at the Plugged Nickel (1965), as inspiration for exploring rhythmic superimposition in standard forms. Waters (2011) Michaelsen (2019) discuss metric modulation and metric dissonance in the music of Miles Davis’s Second Great Quintet. |

| ↵22 | Pulse streams might not be entrainable if the tempo falls outside of the millisecond ranges for beat perception and metricization (London 2012, p. 46). |

| ↵23 | Unlike Figure 6, which presents metric modulations that create a co-meter whose tempo is faster, Ovsepian uses the same process to describe a modulation that leads to a slower co-meter. |

| ↵24 | Pressing (2002) theorizes complex rhythmic interactions in Afro-diasporic music, such as cross-rhythms, syncopation, and polyrhythm, are a form of “perceptual rivalry” that compete for a listener’s metric entrainment. The ensuing play between a referent, such as a formal structure, and a rhythm represents both a broader form of expression in Black diasporic cultures and a distinct characteristic of groove-based music. |

| ↵25 | See Zimmerli (2018) for complete audio track, available through this link. |

| ↵26 | I’ve omitted the piano in the figure for ease of reading. |

| ↵27 | Okazaki explores the visualization of rhythm and pitch into different shapes through his work Fundamentals of Guitar (2015) and 351 Shapes (2022). |

| ↵28 | See Agawu (2003), Locke (2011) Stover (2009 and 2019), and Benadon (2020) for discussions of timeline rhythms |

| ↵29 | Several musicians in the interviews described memorizing the ostinato using this thought process. |

| ↵30 | I use 4/4 instead of the notated 5/4 meter because Zimmerli states the piece can also be performed in 4/4. |

| ↵31 | See Polak et al. (2020), Danielsen et al. (2021) and Jacoby et al. (2023). |

| ↵32 | See Iyer (2017) for the complete audio track, available through this link |

| ↵33 | Agawu (2003) remarks that “the morphology of a topos [short timeline rhythm] should never be divorced from its main beats and referential cycle. If you ignore the role of the unsounded […] you might then be led to think that the first sound you hear marks the beginning of a metrical cycle, that relatively longer durations indicate downbeats, or that downbeats must be ‘filled’ with sound rather than silence” (p. 77). |

| ↵34 | On the possible culture-specific differences between European and African music practices, Temperley (2000) speculates that a listener approaches new music through the metric contexts of the music they are accustomed to: “the Western perception involves shifting the metrical structure in order to better match the phenomenal accents, while the African perception favors maintaining a regular structure even if it means a high degree of syncopation.” (p. 79) |

| ↵35 | See Clayton (2020), Benadon (2020), Polak et al (2016 and 2020). |