“Dream Away the Time”. Metric Play in Benjamin Britten’s

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Aidan McGartland

| PDF | CITATION | AUTHOR |

Abstract

This article examines how meter serves as a key compositional device in Benjamin Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1960), employed in strikingly idiosyncratic ways. Borrowing Leccia’s (2024) notion of “play” as an analytical metaphor, I explore Britten’s diverse metric types and techniques through representative excerpts. Drawing on the metric theories of Lerdahl and Jackendoff (1983) and Rothstein (1989), alongside key Britten scholarship by Rupprecht (2001), I adapt multiple analytical approaches to account for the opera’s stylistic mélange. Four main findings emerge. First, each of the three character groups (fairies, lovers, and rustics) possesses a distinct musical characterisation, including through meter. Second, Britten employs a variety of meters and hypermeters, often integrating irregular rhythms within the larger structure. Third, he manipulates meter and hypermeter to establish models before deviating, typically for narrative effect. Finally, hypermeter interacts with grouping to generate tonal phrases and static atonal hypermetric units.

Keywords: Benjamin Britten; hypermeter; meter; opera analysis; theories of rhythm and meter; twentieth-century music.

Résumé

Cet article met en lumière le rôle central de la métrique comme procédé compositionnel dans A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1960) de Benjamin Britten, où elle est exploitée de manière singulière et inventive. En reprenant la notion de « jeu » proposée par Leccia (2024) comme métaphore analytique, j’examine la diversité des configurations et des procédés métriques chez Britten à partir d’exemples représentatifs. Fondée sur les théories de la métrique élaborées par Lerdahl et Jackendoff (1983) ainsi que par Rothstein (1989), et nourrie par les travaux de référence de Rupprecht (2001), cette étude mobilise plusieurs approches analytiques afin de rendre compte de l’hétérogénéité stylistique de l’opéra. Quatre observations principales se dégagent : d’abord, les trois groupes de personnages – fées, amants et rustres – se distinguent chacun par une identité musicale et métrique propre ; ensuite, Britten déploie une large gamme de structures métriques et hypermétriques, intégrant souvent des rythmes irréguliers dans un cadre plus vaste ; il façonne et détourne ces modèles au service du drame ; enfin, l’hypermètre interagit avec le groupement pour engendrer des phrases tonales ou des unités hypermétriques atonales plus statiques.

Mots clés : analyse d’opéra ; Benjamin Britten ; hypermètre ; métrique ; musique du XXe siècle ; théories du rythme et de la métrique.

Introduction

Benjamin Britten’s 1960 operatic setting of the classic Shakespearean play, A Midsummer Night’s Dream (ca. 1595), is one of his most enigmatic and enchanting works. The work was written rapidly less than a year before its premiere at the Aldeburgh Festival to a slightly reordered and truncated libretto by Britten and his partner, Peter Pears. The opera is notoriously challenging to analyze as Britten employs an idiosyncratic musical language that incorporates a wide palette of styles and techniques, creating an overarching eclecticism and episodic form. Despite being tonally ambiguous, the opera is strongly rooted in triadic tonality, the degree of which varies throughout. As expected in a dramatic work, Britten pays close attention to Shakespeare’s characters, explaining:

Operatically, it is especially exciting because there are three quite separate groups—the Lovers, the Rustics, and the Fairies—which nevertheless interact. Thus, in writing the opera I have used a different kind of texture and orchestral “colour” for each section. For instance, the Fairies are accompanied by harps and percussion; though obviously with a tiny orchestra they can’t be kept absolutely separate (Britten 1960, in Kildea 2003, p. 186).

In addition to timbre and texture, the music for the three groups of fairies, lovers, and rustics is distinguished metrically and rhythmically.

In this analysis of Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, I examine how meter is constructed and then manipulated, often in a playful manner. The opera contains a diverse array of meters and techniques, creating an eclectic collage that defines the work. Owing to this diversity, my analysis cannot do justice to the entire work, so I have selected representative examples. The following discussion of Britten’s meter focuses on four main points. First, each of the three character groups (fairies, lovers, and rustics) have their own metric and rhythmic characteristic tendencies, from the ambiguous meter and non-isochrony of the fairies, to the hypermetric extensions of the lovers, and finally the dotted rhythms, comic tropes, and interrupted isochrony of the rustics. Second, Britten plays with both regular and irregular structures, often shifting between the two. In terms of meter, this usually means isochronous and non-isochronous structures (including some highly asymmetrical ones). This shifting between isochrony and non-isochrony allows the music to reflect the text, to create ambiguity or to interrupt at key moments. Third, the hypermeter is manipulated and transformed throughout. For example, sections often begin with a regular hypermetric model before deviating through a range of techniques, including extension, truncation and overlap, which at times mirror the text and drama. Fourth, rhythm and meter are often derived from the poetic meter of Shakespeare’s text, which can then be used to generate large hypermeter with typically each line of prose forming one hypermetric unit. Additionally, hypermeter frequently interacts with other musical elements beyond meter, especially grouping structures that are commented on where relevant. There are a wide range of grouping structures in the opera, with some manifesting as “tonal phrases,” while others are harmonically static and rhythmically-driven. It is important to note that meter in this study is principally viewed through a perceptual lens, but with music analysis informed by score analysis. Alongside perception, there is also some discussion of compositional process derived through sketches from the archive at Britten Pears Arts that inform the rest of the analysis.1A thorough search through all the sketches, discarded material, and plans uncovered little on meter.

Many aspects of this discussion seem contradictory: there are both isochronous and non-isochronous meters, and they can be either clearly or ambiguously heard. And these extremes often abruptly shift from one to the other throughout the opera. There are two reasonable explanations for this. The first lies with Shakespeare’s play, and the episodic form created by the shifting between the three character groups. In his detailed study of Britten’s reworking of Shakespeare, Mervyn Cooke writes that Britten shortened the play to about half its original length and reworked the dramatic sequence while trying to stay faithful to the original (1999, p. 129). The resultant structure is highly reordered and contains shorter distinct episodes in a symmetrical structure for each act (1999, pp. 130, 133). This provides explanatory context for the quickly evolving and changing sequences of events that are characterized by a wide range of metric techniques. The second explanation is through the playfulness of Britten’s metric manipulation. In his recent dissertation, Marinu Leccia focuses on this “playfulness,” arguing that childlike qualities in Britten’s personality are articulated through his music (2024, pp. 36–38). Leccia defines a playful aesthetic as an:

autotelic reallocation […] [meaning] that it transforms a purposeful activity into an activity made for itself […] [and] consider[s] play as a way of toying with (musical) material (2024, p. 53).

He continues, writing that play depends upon games, which are “challenges of self-imposed limitations” (2024, p. 53). While Leccia’s study does not focus on meter, we can borrow his ideas as an analytical metaphor for meter, especially noting Britten’s frequent use of setting up a model and then quickly deviating in a playful manner. Puck’s mischievous spirit, along with Britten’s decision to cast the fairies as children, further amplify the opera’s playful character.

Music-theoretical literature on Benjamin Britten is limited, focusing predominantly on pitch-based analysis, with many authors employing Schenkerian techniques to highlight the underlying tonality of Britten’s musical language.2See for example: David Forrest (2010), Christopher Mark (1985), Philip Rupprecht (2001), and Christopher Wintle (2006). Noted Britten scholar Philip Rupprecht has published two relevant articles. He devised a model called “tonal stratification” to explain Britten’s “tonal uncertainty,” describing “division of tonal activities into recognizably independent textural regions, strata” (Rupprecht 1996, p. 328), which can be linked to metric layers. In “Quickenings of the Heart: Notes on Rhythm and Tempo in Britten” Rupprecht addresses issues of rhythm, writing that “the communicative power of Britten’s music rests in part on… rhythm… [which is] rarely discussed in depth” (2017, p. 319). He argues that Britten’s use of rhythm shows a “more pronounced concern with the regular and symmetrical” than that of many of his more radical colleagues, as well as touching on the rhythmic repetitiveness that Britten was known for (2017, pp. 319–320). Two sources that focus on meter in the music of Britten are Stuart Paul Duncan’s studies on grouping and displacement conflicts at a local level in earlier works (2017a, 2017b). Unfortunately, there are not many opportunities to engage with Duncan’s work here due to the paucity of metric dissonance in the following examples.

The scarcity of music-theoretic literature on Benjamin Britten extends to A Midsummer Night’s Dream, with only a handful of analytical references, largely commenting on the “four magic chords” from Act II that contain all twelve tones subdivided into four groups, each with a different timbre (Brodsky 2016, p. 169; Cooke 1993, p. 260; Roseberry 1963, p. 37). Beyond music theory, Philip Brett offers some musical insights in his study of gender and sexuality in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1993), while Arnold Whittall’s entry on the opera in The New Grove Dictionary of Opera chronologically outlines the plot, with some musical description (1992). As mentioned above, Mervyn Cooke examines how Britten (and Pears) transformed Shakespeare’s play into an opera, and he includes three tables outlining the complicated episodic structure of the opera that is helpful in viewing the opera as a whole (1993, 1999).

For this study, I have adapted several theories of rhythm and meter. As Britten’s music is still firmly grounded in tonality, I borrow concepts from metric theories originally designed for common-practice repertoire. For hypermeter, I follow David Temperley’s definition of a higher-level “meter above the level of the measure” (2008, p. 305). For meter and rhythm more generally, I take Fred Lerdahl and Ray Jackendoff’s hierarchic approach to metric structures, especially their distinction between “grouping” and “meter,” and secondly, whether these are aligned as “in-phase” or misaligned as “out-of-phase” (1983, pp. 34, 68–104). Most of the discussion on grouping in this article concerns the relationship between phrase structure and hypermeter. I follow Lerdahl and Jackendoff’s analytical notation in which brackets are used to show grouping, alongside large numbers placed between staves to indicate hypermeter. I have adopted William Rothstein’s definition of a “phrase” and its requirement of “tonal motion,” as opposed to a “hypermeasure,” which is a part of an enlarged metric structure that may or may not coincide with a phrase (1989, pp. 3–15). In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, many examples are solely hypermeasures with little harmonic motion, with few examples of tonally oriented phrases. To accommodate Britten’s music, I loosen Rothstein’s definition from “tonal motion” defining a phrase as having some form of harmonic motion, not necessarily an ordered progression as in Rothstein’s model (1989, p. 5). I borrow some ideas of metric dissonance (i.e., the non-alignment of pulse layers) from Harald Krebs, notably his discussion of “grouping dissonances” (1999, pp. 31–32).3Krebs defines grouping dissonances as a type of metric dissonance, involving at least two pulse layers whose interpulse durations are not multiples or factors of one another (e.g., a half-note pulse versus a dotted-half-note pulse) (1999, pp. 31–32). The term “structural downbeat” is taken from Edward T. Cone who defines it as an “important poin[t] of simultaneous harmonic and rhythmic arrival” (1968, p. 24). Last, I note the limits of psychological perception of meter, as there are a few moments when the hypermetric unit is too large to be audibly perceived (notably in the opening), and at this point hypermeter functions as an abstract analytical structure.4Justin London writes that “conversely, the upper limit is around 5 to 6 seconds, a limit set by our capacities to hierarchically integrate successive events into a stable pattern” (2012, p. 27). This is what Richard Cohn has recently termed “deep meter” (2023).

Setting Shakespeare’s Text

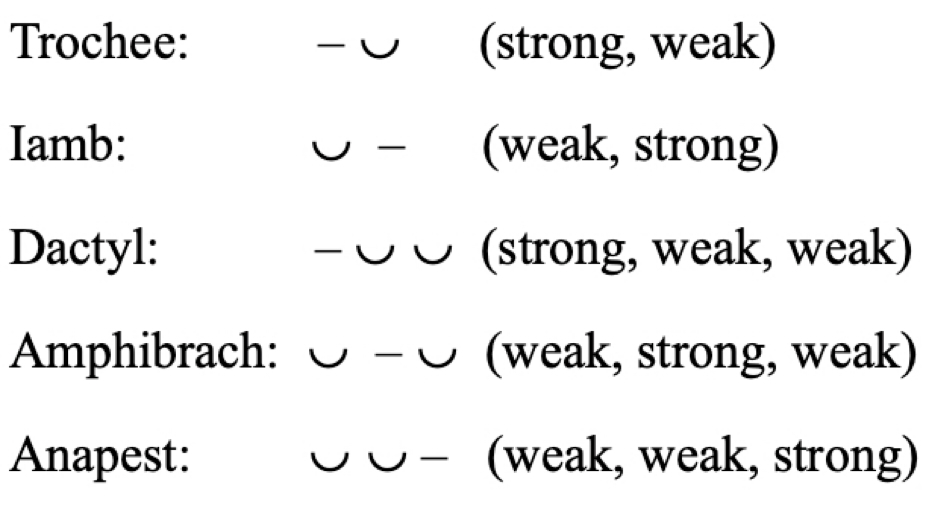

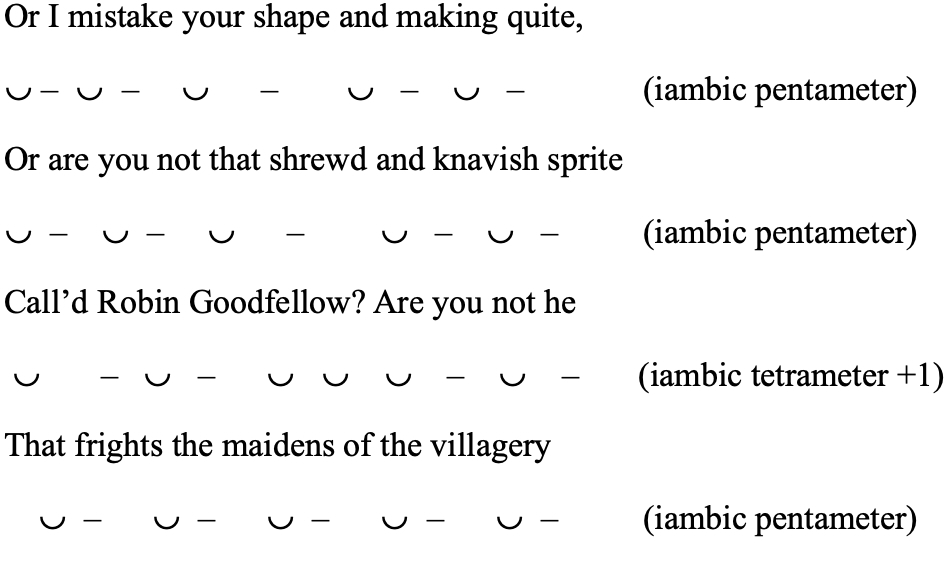

Much of the meter and the resultant metric characteristics of A Midsummer Night’s Dream are likely derived directly from Britten’s careful readings (and deliberate misreadings) of the poetic meter of Shakespeare’s text. Unlike the subsequent sections, this section focuses primarily on the conceptual rather than the perceptual end of meter. It compares Shakespeare’s text with Britten’s setting in an attempt to recreate the compositional process of the text-setting (noting there is a lack of primary sources that illustrate this). This would suggest that Britten’s consideration of poetic meters occurs towards the start of his compositional process. Poetic feet can be expressed musically either by duration (long versus short) or by accent (strong versus weak), as in Shakespeare’s text. In all the following examples, the text is almost always set syllabically, with few melismas, allowing Britten to more closely follow the poetic meters of Shakespeare’s text and ensuring that they are clearly communicable. Figure 1 outlines the types of disyllabic and trisyllabic feet that are discussed throughout this paper. These poetic feet are organized in groups creating a line of verse. For example, “dactylic trimeter” means there are three dactyls in a line, “trochaic tetrameter” is four trochees, and most famously “iambic pentameter” is five iambs.

Figure 1: The main poetic feet discussed in this article.

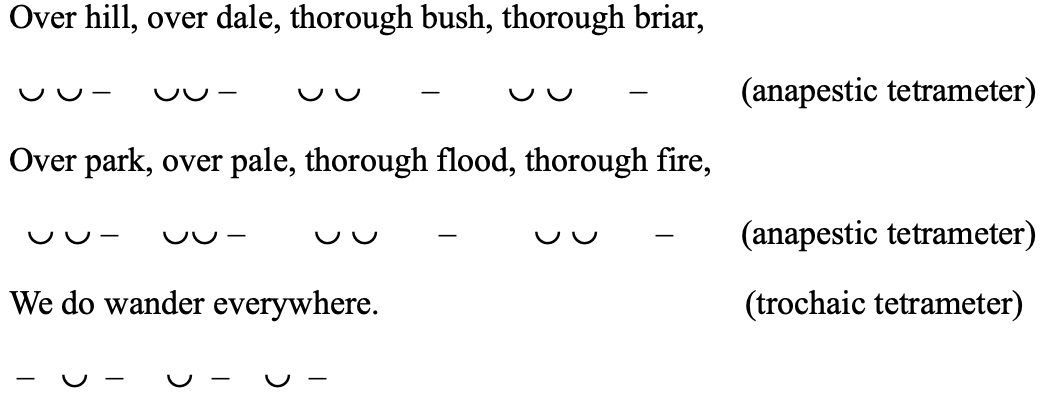

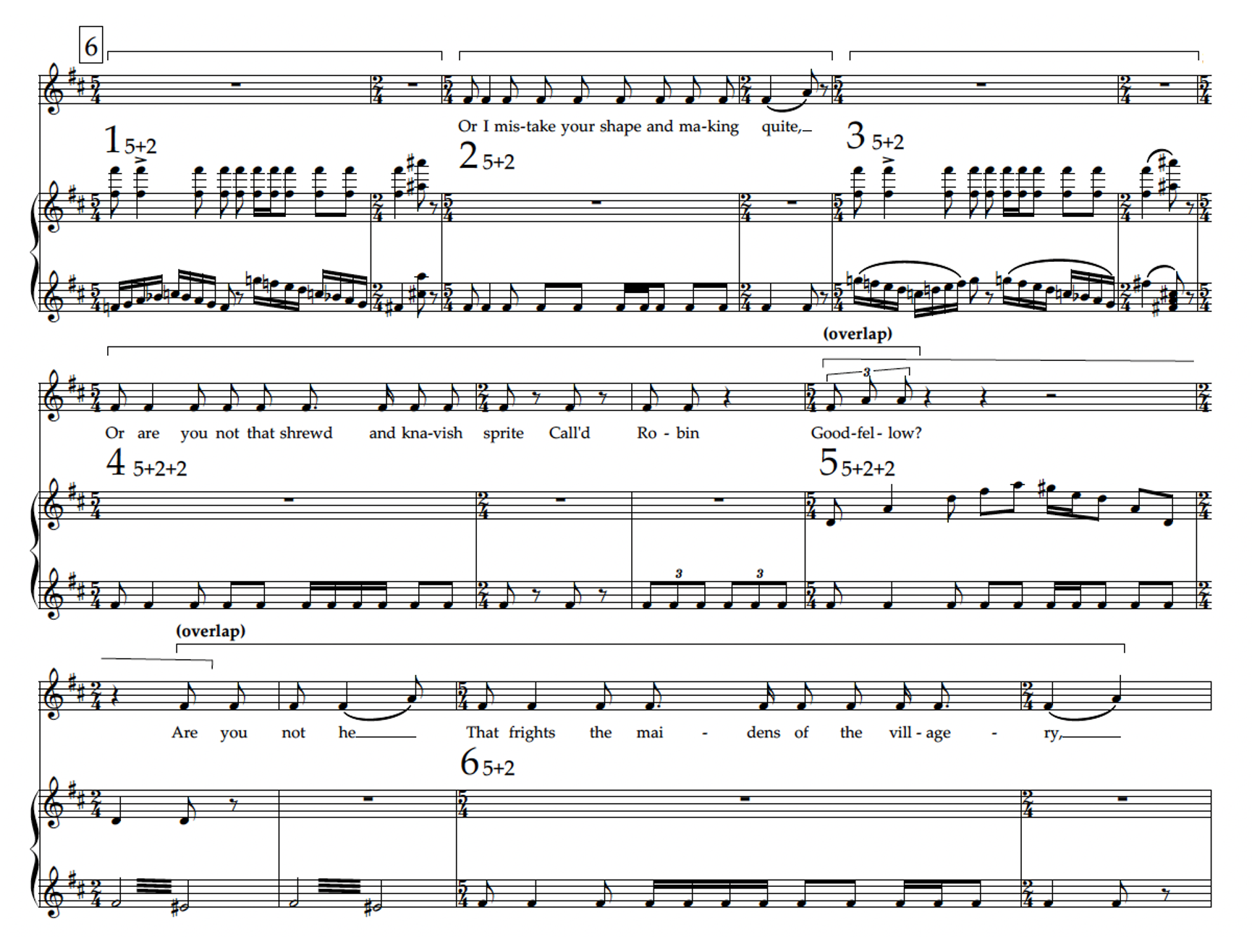

The first example is Shakespeare’s signature use of iambic pentameter in “Or I mistake…” (Figure 1a). In Britten’s setting (Figure 1b), the natural accents of the text are metrically preserved. However, his model is syncopated alongside employing non-isochronous meter. It commences with syncopation, with the second eighth note being accented and lengthened, strengthening the first iamb. This line of iambic pentameter is then set in a model consisting of one 5/4 measure joined to a 2/4 measure to create one large 7 (5+2) beat hypermeasure (note that the time signature is actually marked “5/4 2/4”). Having two alternating measures of different lengths is a feature of Britten’s writing for the fairies in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The rationale here is that Britten could thus place a strong downbeat on the last syllable (“quite”), as well as being able to freely add more 2/4 measures in a kind of additive process (shown later in Figure 5b). The vocal line is then directly echoed by the orchestra, creating a call-and-response structure that is discussed below.

Figure 1a: Shakespeare’s poetic meter of “Or I mistake…”

Figure 1b: Britten’s musical setting of “Or I mistake…,” fairies, Act I (Britten 1960, pp. 5–8).5Note that Britten does not distinguish between 5/4 and 2/4 in the score, writing “5/4 2/4” as the time signature. For this analysis I have written them both in for clarity. Dynamics and articulation have been largely removed from the following examples. © 1960 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. © Renewed 1988 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reproduced with permission from Boosey & Hawkes.

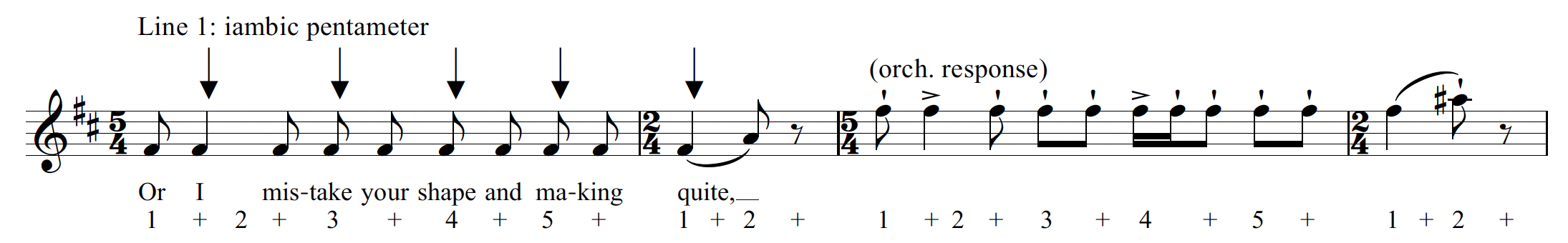

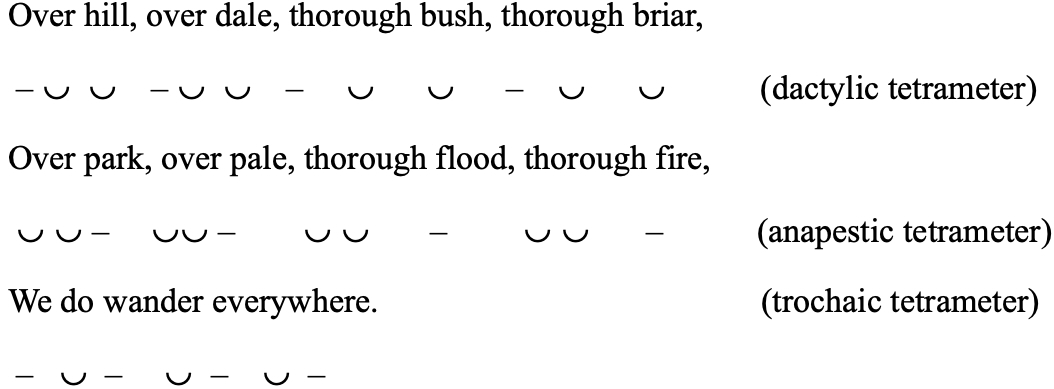

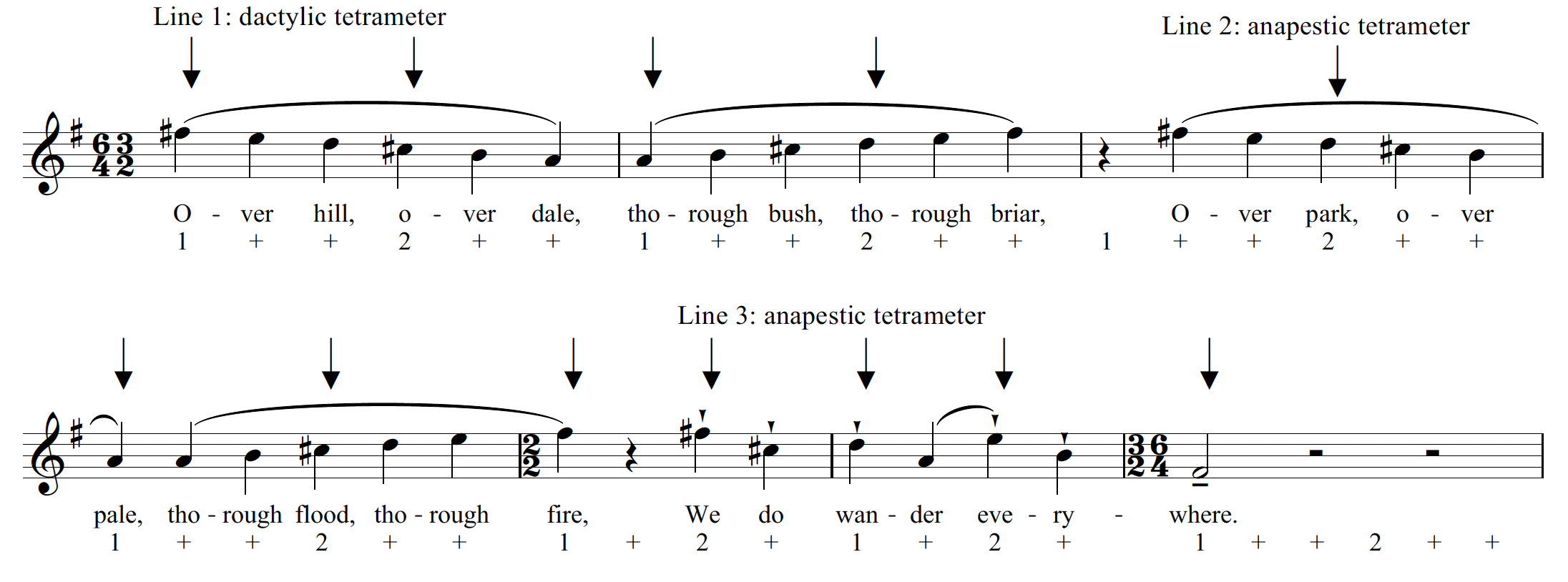

In the next two examples, the meter of Britten’s settings of Shakespeare’s original poetic feet do not coincide. Figure 2 (a, b and c) demonstrates the process of text setting at the opening of the opera.6Originally not the opening of the play but reordered by Pears and Britten. The fairies enter with an unequal tercet, the first two lines being originally anapestic tetrameter, while the third line abruptly shifts from three-syllable groupings to two, resulting in trochaic tetrameter. Britten alters the poetic meter of the first line, making it dactylic tetrameter with emphasis placed on the first syllable of “Over,” rather than “hill” and “dale.” He seemingly transforms this anapest into a dactyl to create metric ambiguity. The second line is then shifted by a quarter note, creating a metric displacement, and making it seem out-of-phase with the orchestra. Practically, this rest leaves a short breath for the singers, as well as delineating the two opening lines. Following the text, Britten preserves the third line’s trochaic meter in 2/2. The abrupt shift makes it feel like a rhythmic cadence (with clear change of harmony and texture), demarcating the end of the section, before returning to repeat the pattern (and returning to the G-major centre).

Figure 2a: Shakespeare’s poetic meter of “Over hill, over dale…”.

Figure 2b: Britten’s poetic meter of “Over hill, over dale…”

Figure 2c: Britten’s musical setting of “Over hill, over dale…” with arrows indicating alignment of metric and textual accents, fairies, Act I (Britten 1960, p. 2).7 © 1960 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. © Renewed 1988 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reproduced with permission from Boosey & Hawkes.

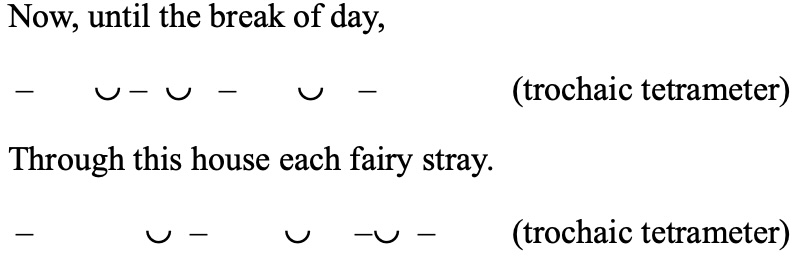

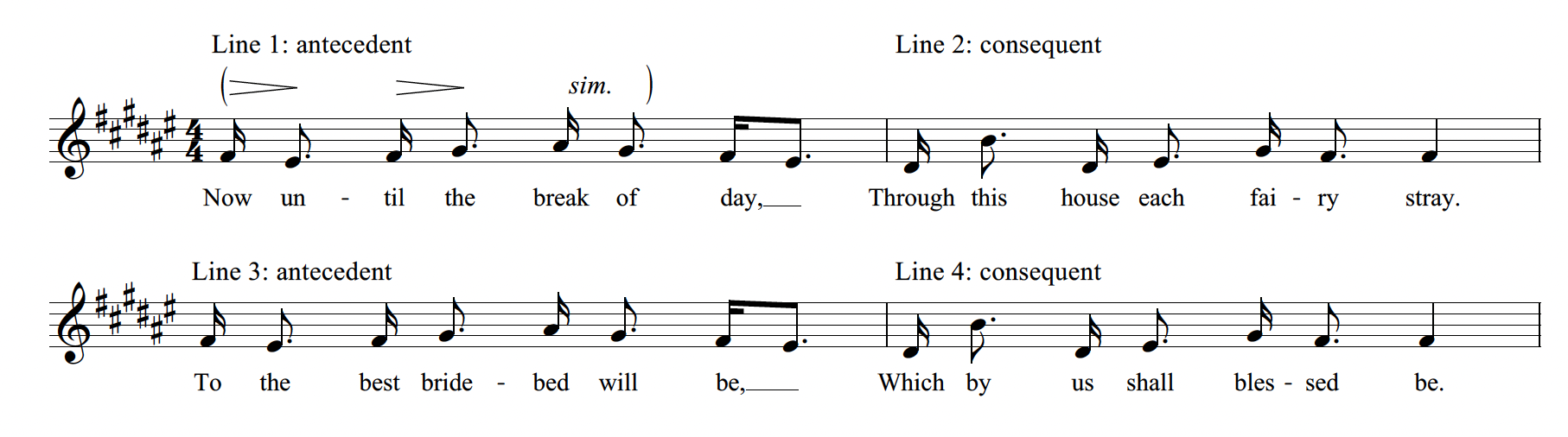

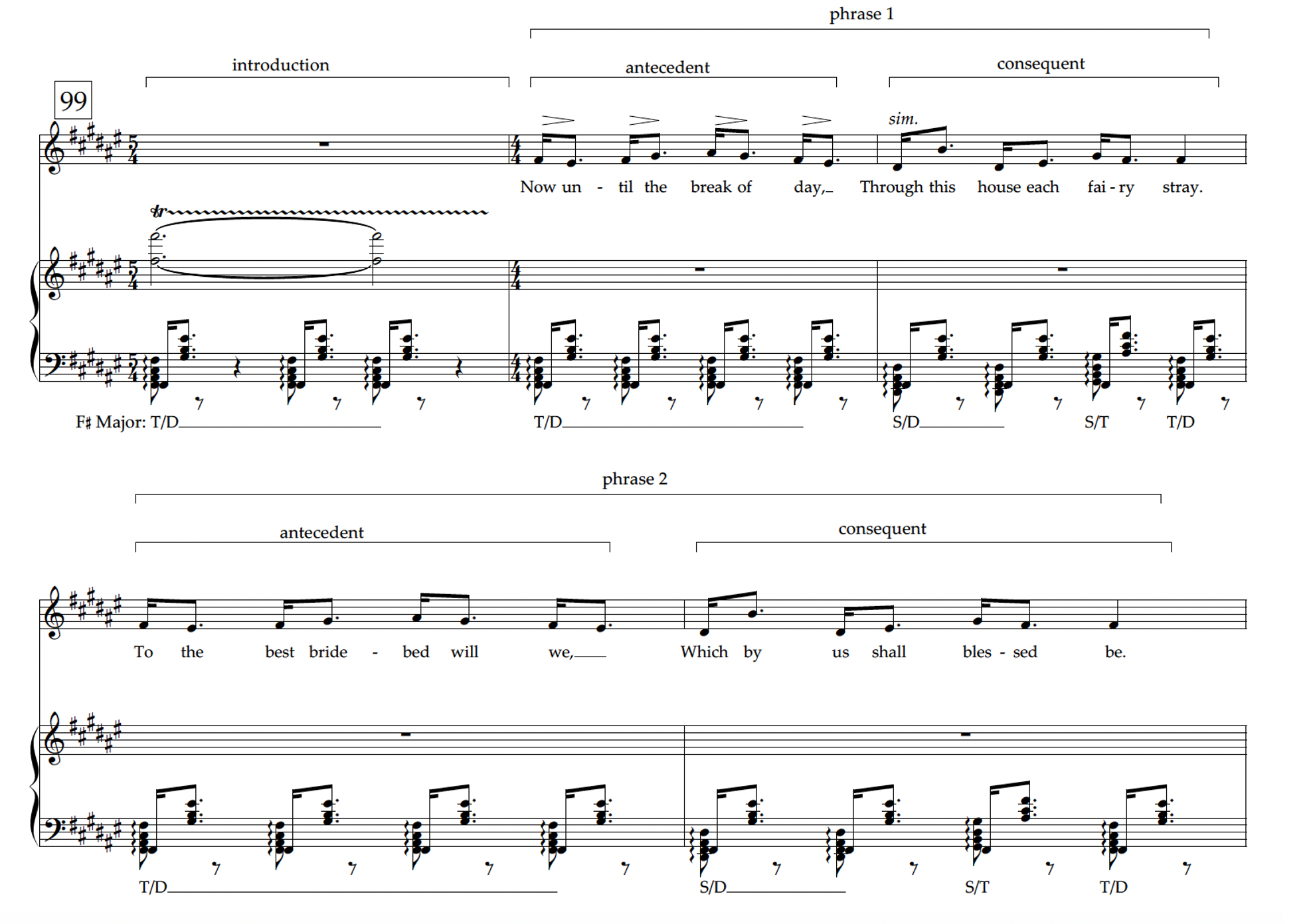

Britten’s setting of the original trochaic tetrameter in Figure 3a is rather ambiguous. He reverses the emphasis by setting these trochees as iambic Scotch snaps. However, the diminuendo markings above make it clear that the first note should be louder. This creates a conflict between stressed trochees signified by the diminuendo markings and the durational iambs notated by the Scotch snaps. Ultimately it is the trochaic structure of the text that is heard and emphasized by the performers, but the durational iambs nonetheless weaken this structure. The couplet structure is preserved, with each line forming one measure and a two-measure hypermeter. The first measure acts as an antecedent and moves towards 7̂, which is answered by a consequent in the next measure that squarely lands on 1̂. This illustrates how text-setting is used to generate both hypermeter and melodic phrases, which align in this instance.

Figure 3a: Shakespeare’s poetic meter of “Now until the break of day…”.

Figure 3b: Britten’s musical setting of “Now until the break of day…,” fairies, Act III (Britten 1960, pp. 308–309).8© 1960 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. © Renewed 1988 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reproduced with permission from Boosey & Hawkes.

Setting the Scene in the Athenian Woods

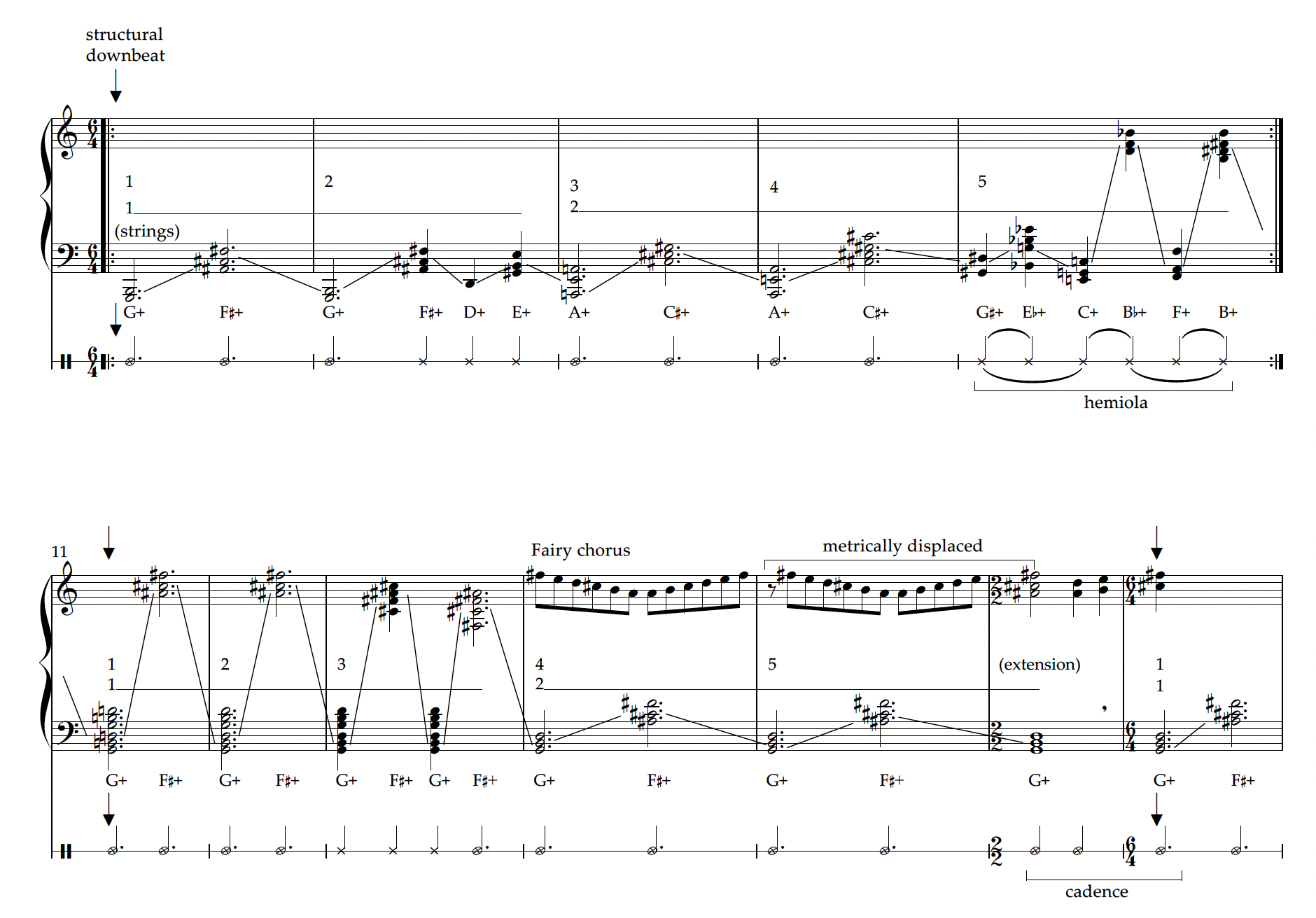

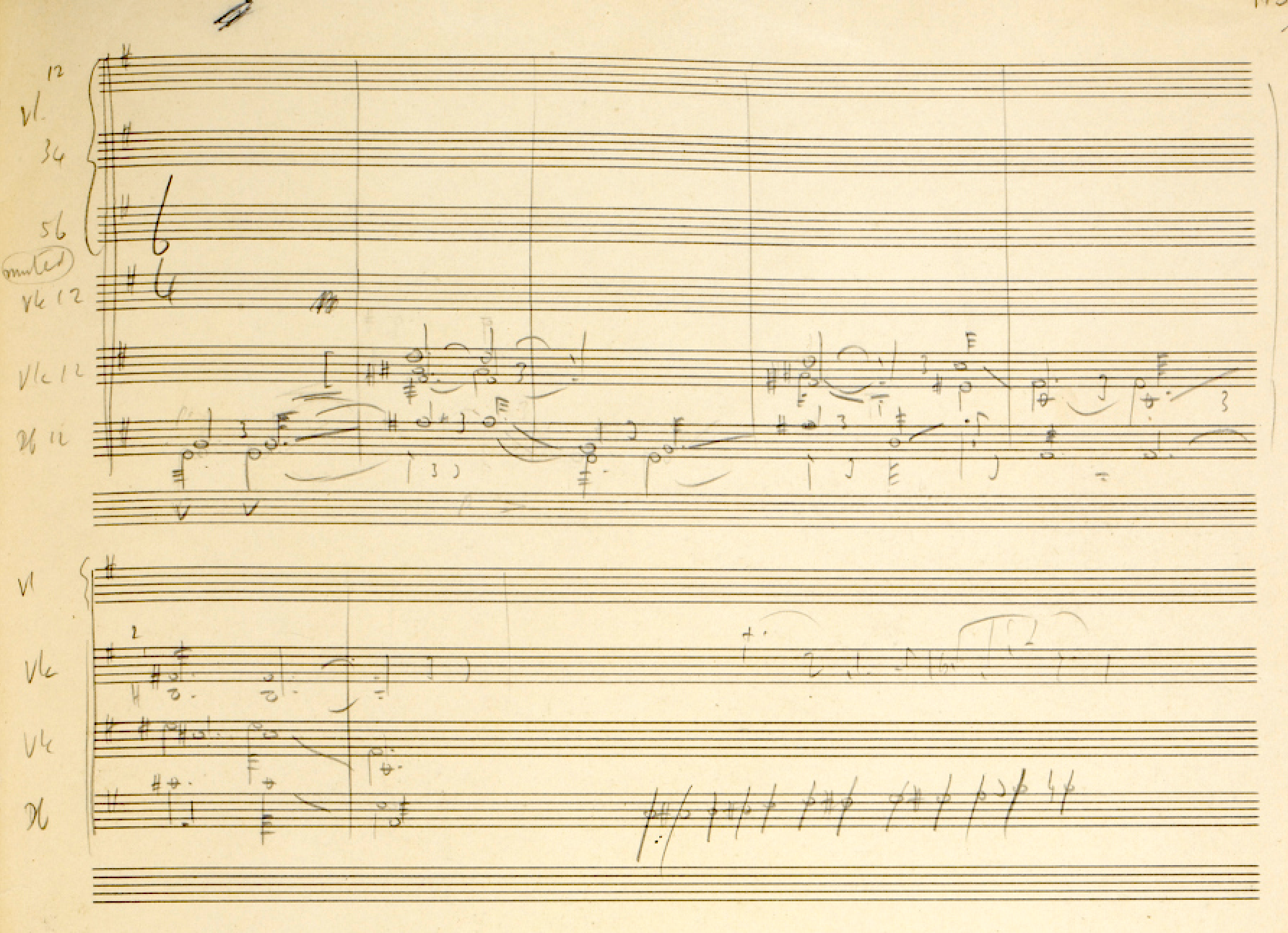

The most ambiguous, irregular, and intriguing example of meter occurs at the opening of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, with the “portamenti strings” (Brett 1993, p. 269) that function as a ritornello throughout Act I (Cooke 1999, p. 133). This opening aptly reflects the mysterious Athenian woods where the realm of fairydom lies. The meter and the resultant hypermeter are both highly ambiguous, in part due to the soft dynamic and the sliding of the strings, but also due to Britten’s notation of the time signature as “6/4 3/2” (Figure 4a). Most of the measures are in 6/4, but there are occasional measures of 3/2 without a clear pattern, creating further metric uncertainty. A hypermetric structure gradually emerges with two structural levels (Figure 4b). The more overt level is the two-measure hypermeasure, which correlates with the contour, the downbeats being the lower registral extreme. However, there is an even deeper level of hypermeter that consists of a 10 measure—or really 5 x 2 measure—hypermeter that repeats three times (indicated in the metric reduction between the staves of Figure 4b). This creates a large non-isochronous hypermeter that is not possible to be perceived, instead functioning as a more abstract conceptual structure.9This large 5 x 2 hypermeasure is too slow to be perceived as meter per se, and is purely an abstract device (see London 2012, p. 27). This adds to the metric ambiguity, and the mystic aura, despite the overt structural downbeats (marked in Figure 4b) on prominent arrival points, on the tonic and in hypermetrically strong positions. At the end of each hypermeasure, rhythmic diminution signals closure and aligns with the change in poetic meter to trochaic tetrameter. In m. 21 (rehearsal mark 1), a very clear structural downbeat occurs, consolidating the G-major center, and preparing for the entrance of the fairy chorus who are then subsumed into the hypermetric structure. Register is an important parameter in this hypermetric analysis, as the strings slide between G major in a low register (and on stronger beats) and F# major in a high register (on weaker beats), until the two converge at the entrance of the fairies, reinforcing the hypermetric structure. This use of demarcation by register connects with Rupprecht’s idea of “tonal stratification” (1996).

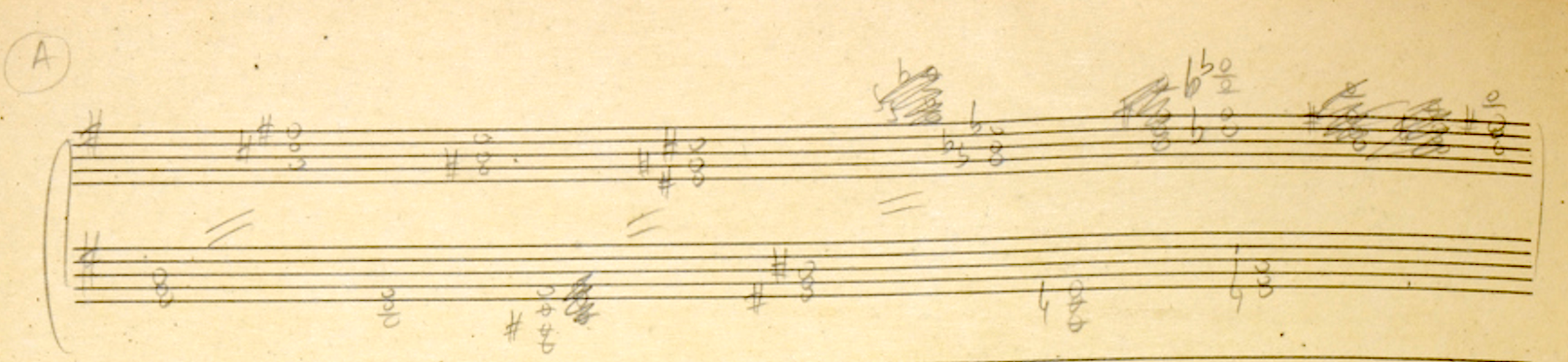

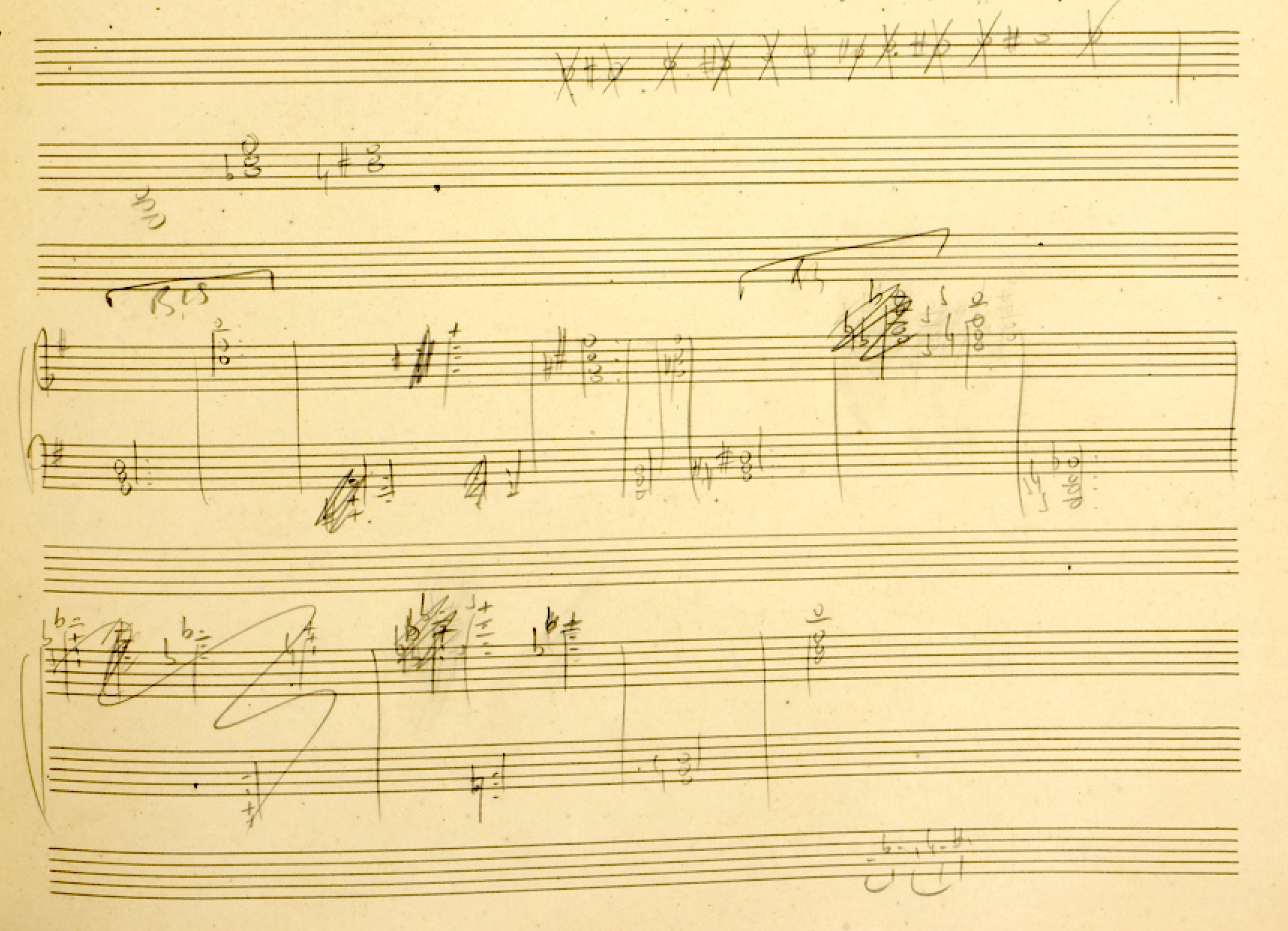

To see how this relates to the metric structure, I will briefly survey the compositional process through the sketches. Importantly, these sketches illustrate process rather than definitive proof of the metric structure, in that the metric structure appears after the established pitch structure. The first stage in Figure 4c shows no discernible notated meter, instead focusing on the twelve major triads placed in different registers with lines between indicating or foreshadowing the sliding. The next stage (Figure 4d) adds a clear metric structure to the twelve triads.10Note Britten’s twelve-tone checklists in the margins, ensuring that all twelve major triads have been covered The meter appears to be 3/4 with some of the triads taking up a whole measure as dotted-half notes, while others are quarter notes with no discernible pattern. The last stage in Figure 4e shows how the excerpt is then orchestrated into essentially the final form. The 3/4 measures have expanded into 6/4 measures, creating more metric uncertainty as the triple grouping is retained in some measures, creating a grouping dissonance. Additionally, the orchestration obscures the meter, allowing for the perceptible structure to be more similar to the metric freedom of Figure 4c. The meter is notated as 6/4 despite the fourth measure being grouped as a 3/2 measure, implying that the final “6/4 3/2” metric marking came after this. From these sketches, it can be deduced that Britten envisaged that both the meter and the twelve-tone structure be destabilized and rendered ambiguous. Thus, this justifies the complexity and ambiguity in the perceptual analysis of Figure 4b.

Figure 4a: Score of the opening of Act I, fairies (Britten 1960, pp. 1–2). See Figure 4a.11Recording: Benjamin Britten. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Benjamin Britten. Decca, 1967, CD, https://youtu.be/QRfR-nvI8Uo?si=yrriDaZ1_AYobHiS © 1960 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. © Renewed 1988 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reproduced with permission from Boosey & Hawkes.

Figure 4b: Metric reduction (2:1). Triads in order: G F# D E A C# G# Eb C Bb F B

Figure 4c: Sketches of the opening: discarded material of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, c. 1960, BBM/a_midsummer_nights_dream/2/2, p. 113, Britten Pears Arts Archive. 12 © Britten Pears Arts (brittenpears.org).

Figure 4d: Sketches of the opening: discarded material of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, c. 1960, BBM/a_midsummer_nights_dream/2/2, p. 114, Britten Pears Arts Archive. 13 © Britten Pears Arts (brittenpears.org).

Figure 4e: Sketches of the opening: discarded material of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, c. 1960, BBM/a_midsummer_nights_dream/2/2, p. 115, Britten Pears Arts Archive.14© Britten Pears Arts (brittenpears.org).

The Fairies

In order to show the distinctive musical identity of each, beginning in the realm of the fairies and moving through to the mortals, the following section is organized around the three character groups. Britten’s setting of the fairies tends to be less normative and less tonal in general than that of the mortals. In terms of meter, this means a greater use of non-isochrony and metric ambiguity, alongside an obscuring of tonality. Together these elements are used to portray the mysterious and supernatural nature of fairydom. The following examples illustrate the range of different metric structures in the fairies’ music across the opera, from the mysterious opening to Oberon’s aria-like passage “Be it on Lion.” Many of the following examples are drawn from the fairies’ material, as they contain some of the more distinctive metric techniques in the opera.

Britten’s setting of “Or I mistake…” comprises 18 hypermeasures in total (Figure 5a), with each hypermeasure derived from one line of text that is set as one 5/4 measure joined to a 2/4 measure (see Figure 1b). The material is passed from the orchestra to the fairy chorus and back, creating a call-and-response effect. The first three hypermetric units follow the model strictly (see Figure 5b), with the phrases and hypermeter aligning as in-phase. This changes at hypermeasure 4 where the third line of text, “Call’d Robin Goodfellow? Are you not he,” is split into two parts, as the poetic meter has momentarily changed from iambic pentameter to iambic tetrameter (with an extra beat), as shown in Figure 1a. The first part is added to the previous vocal phrase that begins in-phase. Hypermeasure 4 is extended by two beats and the vocal phrase then overlaps with hypermeasure 5 by two beats, concluding the phase with “Goodfellow,” making the phrase and hypermeter out-of-phase. The second part of the line, “Are you not he,” occurs in the last part of hypermeasure 5 and begins the next vocal phrase. At first glance it appears odd that Britten would choose to partition Shakespeare’s line, but it does make grammatical and poetic-metrical sense, as the question ends with “Goodfellow” before a new sentence commences. This demonstrates the careful attention given not only to the structure of the text, but also to its meaning. It is noteworthy that harmony is very static in this section: the fairy chorus mainly sings a relentless repeated F#, with the momentum coming from the syncopated rhythms and the non-isochronous meter, instead of harmonic motion.

Figure 5a: “Or I mistake…,” fairies, Act I (Britten 1960, pp. 5– 8).15Recording: Benjamin Britten. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Benjamin Britten. Decca, 1967, CD, https://youtu.be/QRfR-nvI8Uo?si=9w93fUGMfGVgeoE1&t=167 © 1960 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. © Renewed 1988 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reproduced with permission from Boosey & Hawkes.

Figure 5b: Structural diagram (Act I).

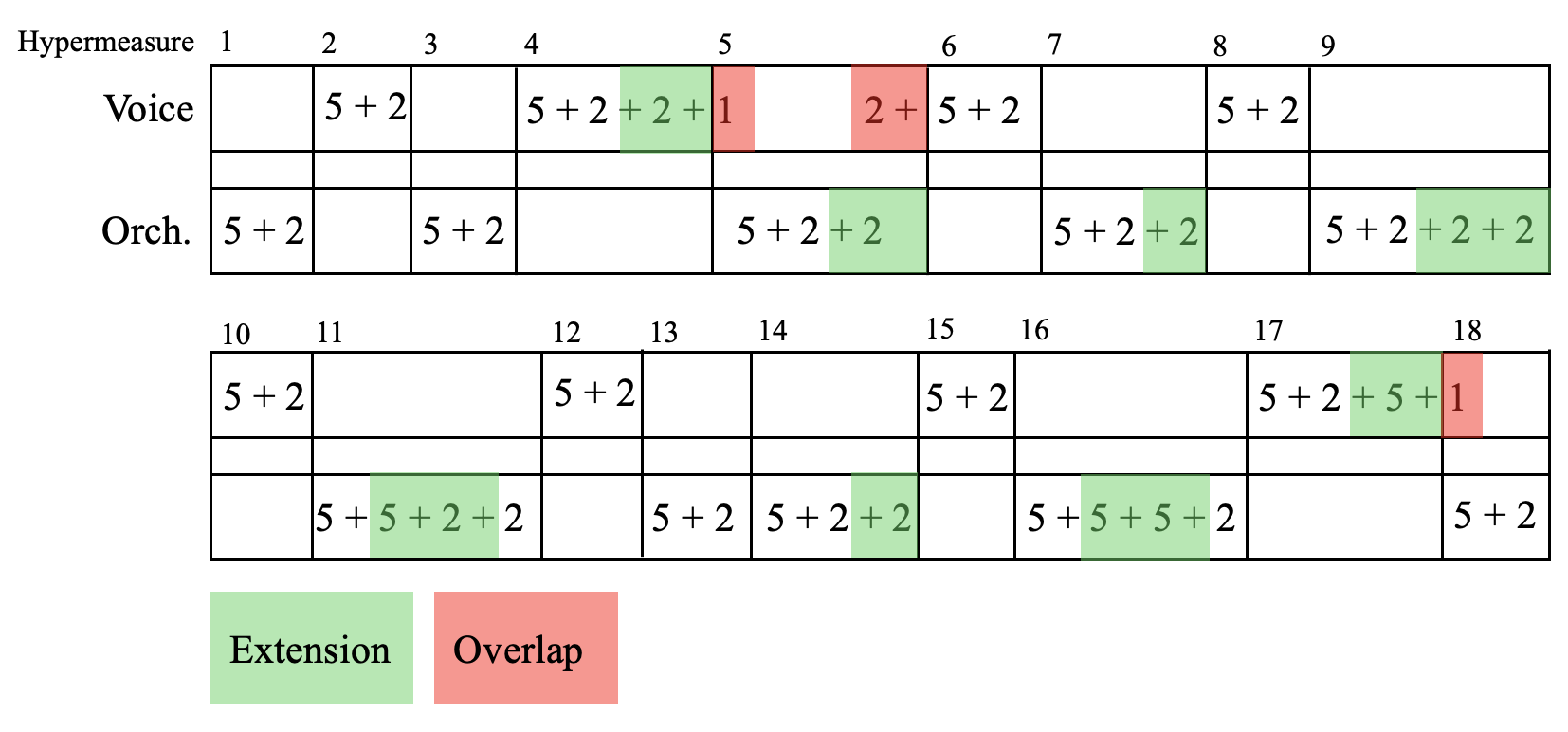

In the case of Oberon, the fairy king, he is characterized throughout A Midsummer Night’s Dream by a chromatic leitmotif shown in m. 5 of Figure 6 that is used to generate the melodic content of “Be it on Lion, Bear or Wolf…”16Oberon’s leitmotif is created by three chromatically adjacent minor thirds (see m. 5 of Figure 6). The consequent of mm. 7–8 is related by an I7 transformation. Preceding Oberon’s entry is a version of this leitmotif in the solo violin at rehearsal mark 35, mostly following the 6/8 grouping. An exception is m. 2, where the violin switches into 3/4 grouping before reverting to 6/8. Underneath the violin solo, a celesta accompaniment is organized by contour into duple groups, implying 3/4. This creates a hemiolic metric dissonance between the 6/8 triplet groupings of the violin solo, which is a “grouping dissonance” in Krebs’ system owing to the conflict between these two pulse layers. Oberon then enters in m. 5 and the triplets preserve the dactylic trimeter of the text over the metrically dissonant celesta.

An even more in-depth examination reveals that the hypermeter notated in Figure 6, mm. 5–6 can be fused together as an antecedent and mm. 7–8 as a consequent (the hypermeter and grouping are in-phase). However, the violin enters in canon midway through the second hypermeasure, suggesting a new hypermeter, cast like a shadow, before all is abruptly halted as the mortal lovers appear.17This canon resembles what James Sullivan discusses as “close imitation” (2021). The only difference is that this is spaced out, making it less close (and it abruptly stops), but it is ultimately rooted in the same technique of imitation. This interruption by the violin destabilizes the hypermeter, and alongside the lower-level metric dissonance, musically reflects the interruption of the mortals.

Figure 6: “Be it on Lion…” Oberon, Act I (Britten 1960, pp. 31–32).18Recording: Benjamin Britten. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Benjamin Britten. Decca, 1967, CD. https://youtu.be/b-NFjXtAT-4?si=dwgX0vwvaNny8fP0 © 1960 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. © Renewed 1988 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reproduced with permission from Boosey & Hawkes.

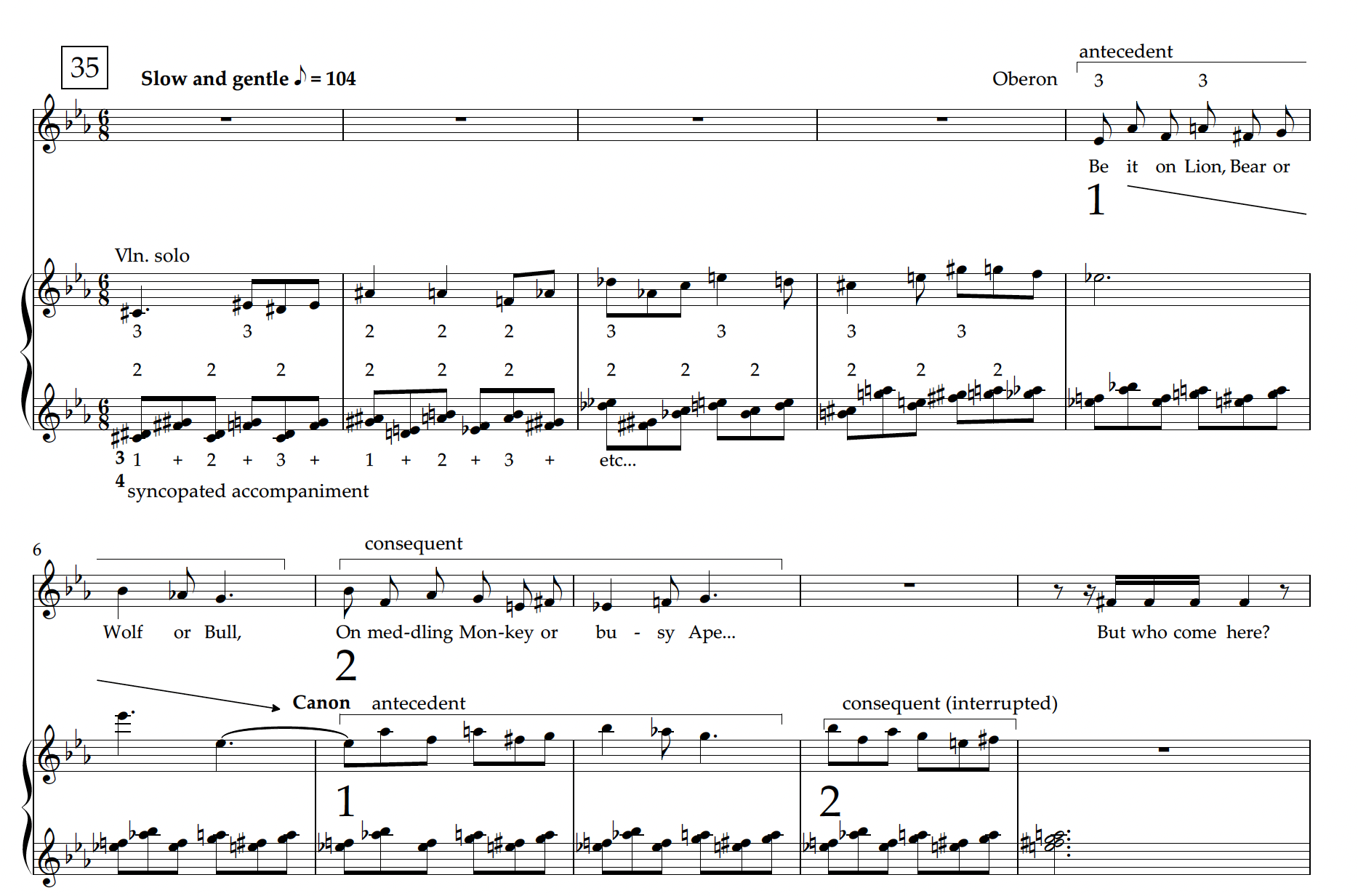

Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream concludes with the fairies’ finale, “Now until the break of day,” when the mortals have gone to bed, and all is resolved dramatically (Figure 7a; after Figure 3). Mirroring how the many conflicts of the plot have been resolved, the finale provides metric resolution with a regular, isochronous 4/4 pulse with six duple metric levels (Figure 7b)—the first time for all the fairies.19This structure is what Richard Cohn would call “pure duple” as each of the six metric levels is duple (1992, 194). The overt hypermeasure comprises two measures, with a functional tonal progression underneath, creating phrases that are in-phase with the hypermeter. In short, while being mostly regular and mostly tonal, this excerpt nevertheless contains a few quirks that make it clear that we are still in the realm of the fairies (see the functional analysis in Figure 7a).

Figure 7a: “Now until the break of day…,” fairies, Act III (Britten 1960, pp. 308–309).20Recording: Benjamin Britten. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Benjamin Britten. Decca, 1967, CD, https://youtu.be/hSCH-DTlpXk?si=X8ygyxrAG2JD6PuX&t=120 © 1960 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. © Renewed 1988 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reproduced with permission from Boosey & Hawkes.

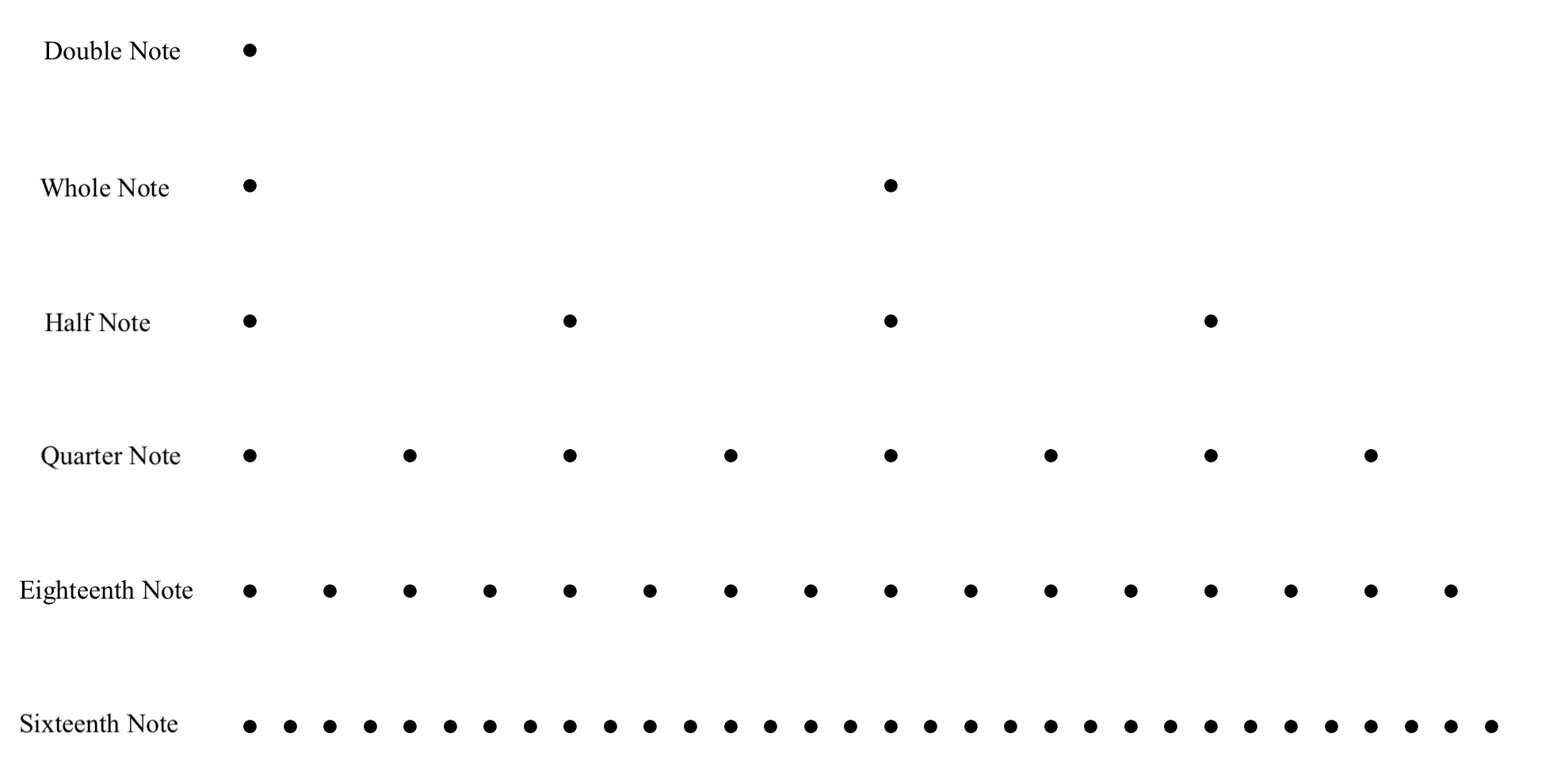

Figure 7b: Isochronous metric layers.

The Lovers

The lovers are the second character group and are generally characterized by a dreamy, romantic aesthetic that manifests as rambling phrases with triadic harmonies and flowing, expressive vocal lines. Owing to their mortal status, the setting of the lovers is much more tonally oriented and metrically isochronous than that of the fairies. The aforementioned dreamy aesthetic is aided by the hypermetric extensions discussed below.

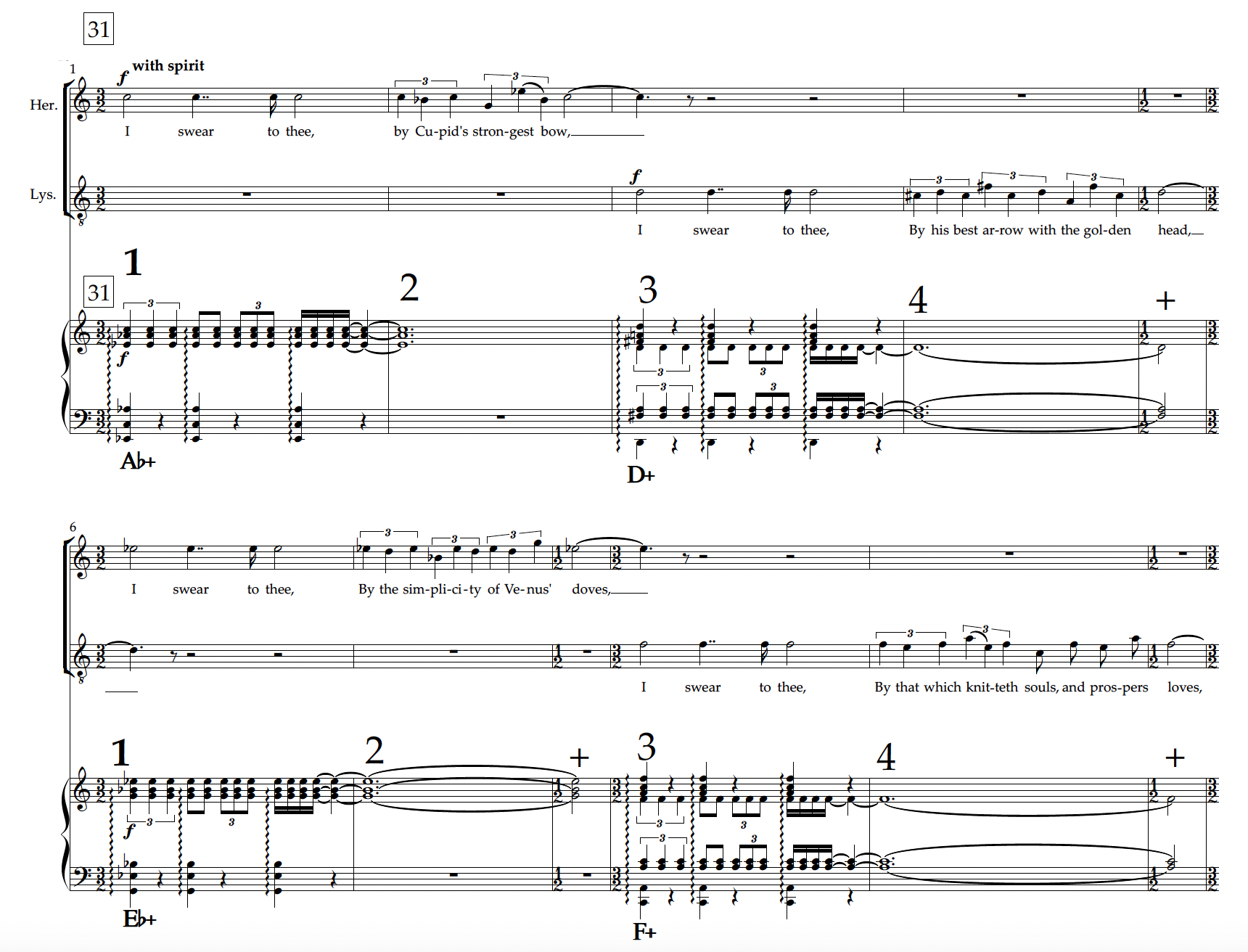

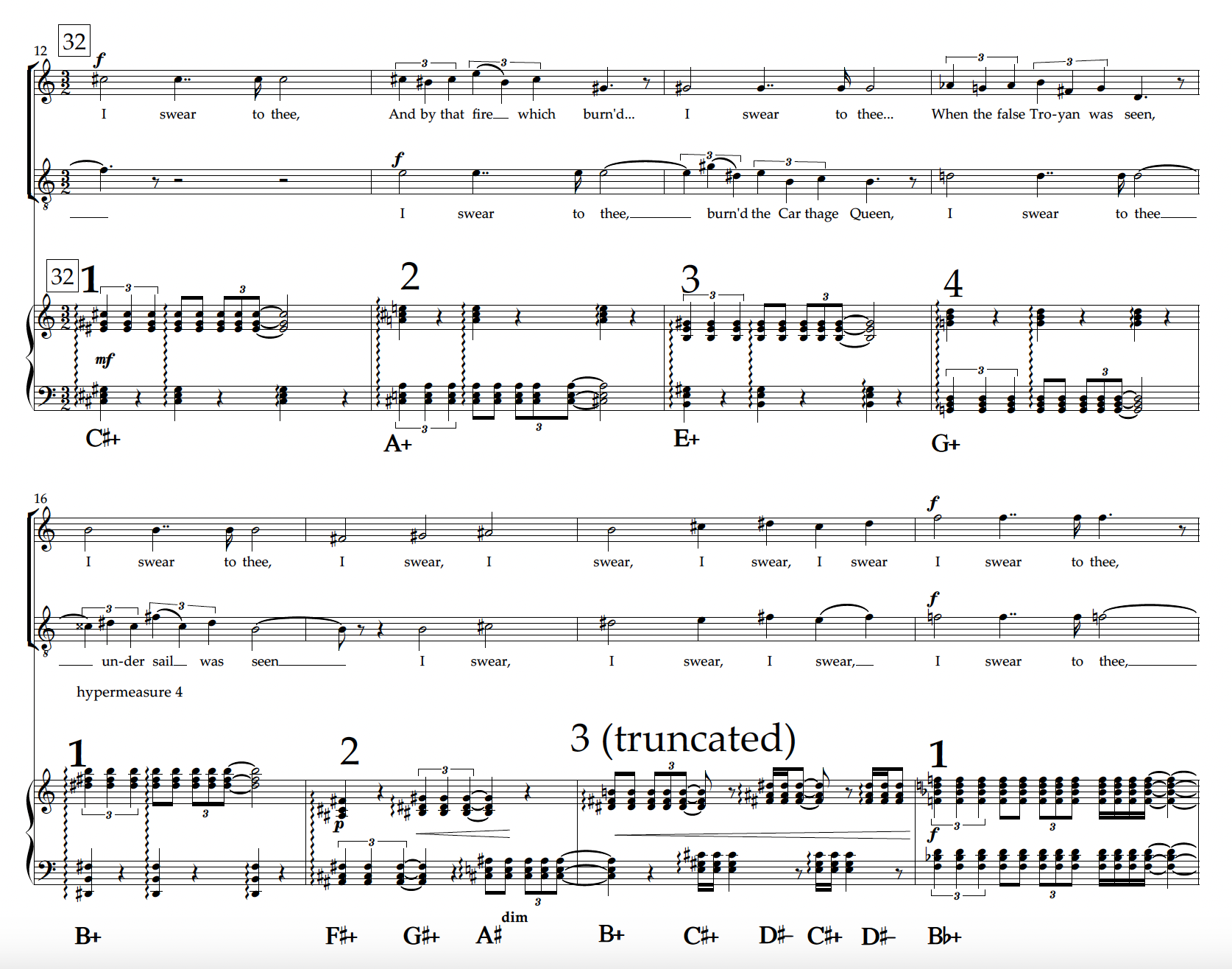

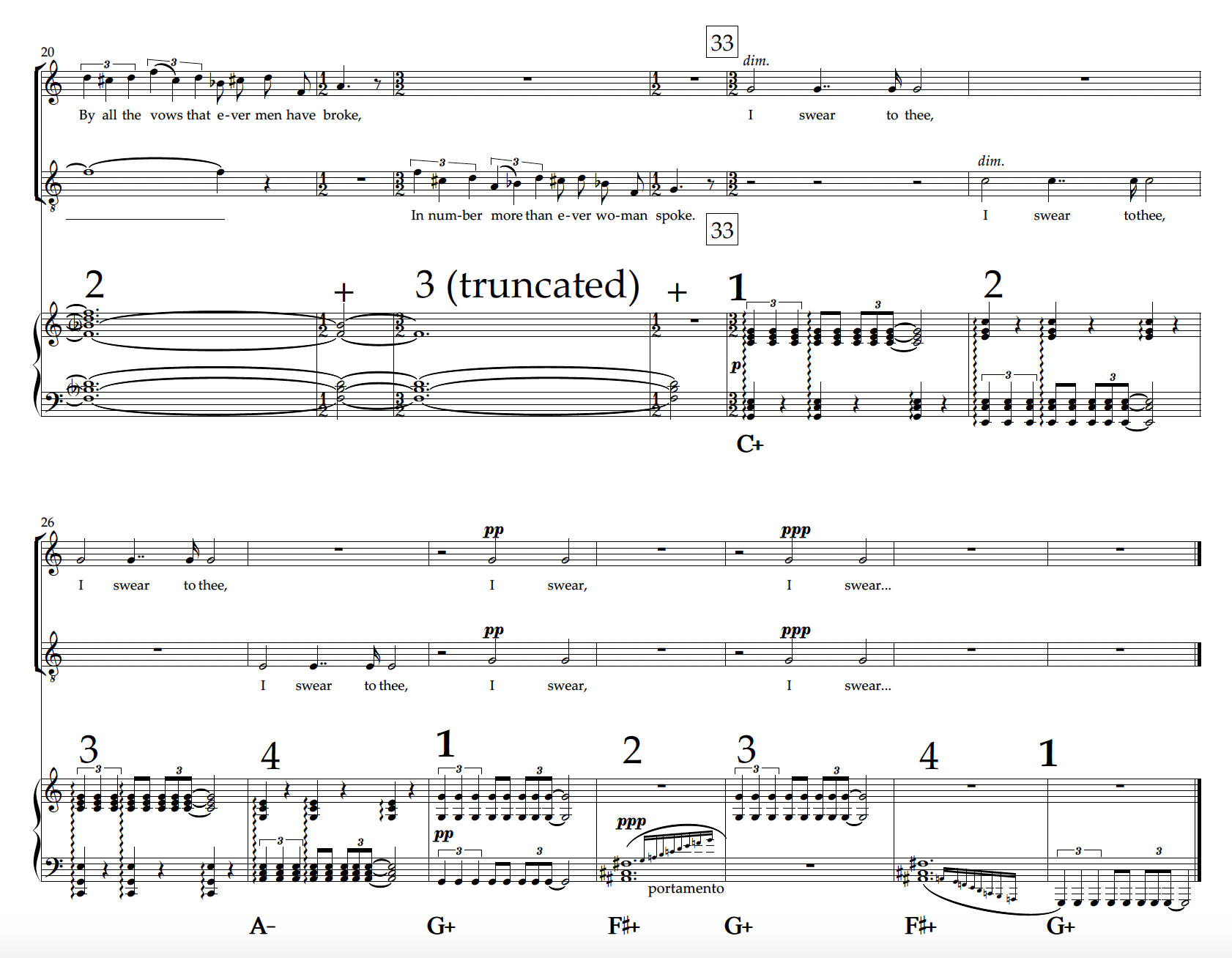

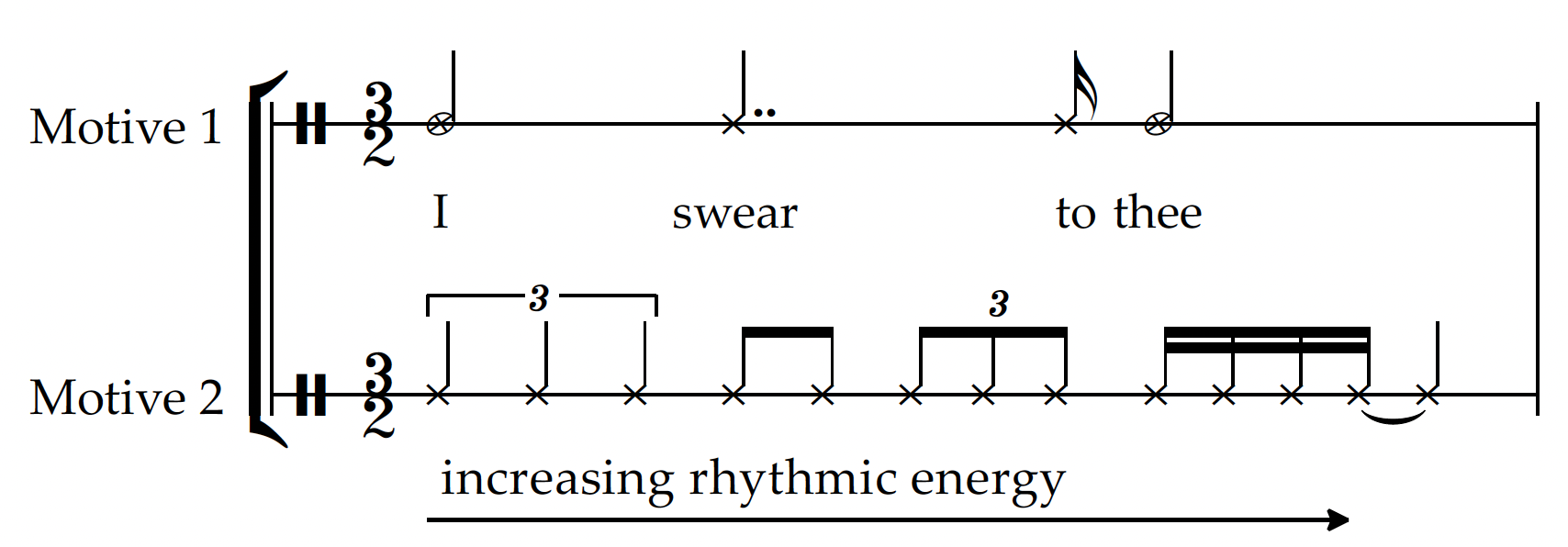

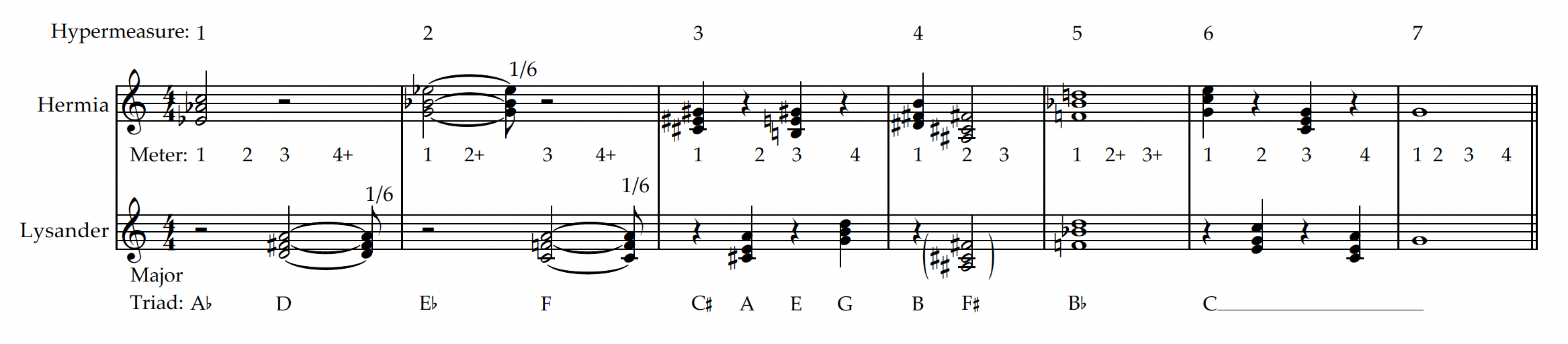

The duet “I swear to thee” is a representative example of the soundworld of the lovers. It is notable due to the process of hypermetric extension and truncation (Figure 8a). The excerpt is characterized by two motives. Motive 1, setting “I swear to thee,” is derived directly from the natural rhythm of the words, and it occurs whenever the text reappears (Figure 8b). This vocal motive (1) is accompanied by an instrumental Motive 2, defined by rapid rhythmic diminution, which occurs from supertriplets down to sixteenth notes, accompanied by 3 rolled chords to demarcate the triple meter. The hypermeter comprises four measures of 3/2, often with a short 1/2-measure extension, elongating the last beat, as in hypermeasure 1. These short extensions divert the listener’s attention from the already long beats of the hypermeasure. The resultant effect is a dreamy uncertainty with the hypermetric structure more conceptual than perceptual. The structure of the hypermeasure is organized around the duet between Hermia and Lysander, with Hermia singing in the first two measures, and Lysander responding in the second half. This structure can be seen more clearly in the reduction of Figure 8c.

At the commencement of the duet, the motive and the hypermeter align, with the motive marking the start of each hypermetric unit. This soon liquidates in hypermeasure 3, as the duration between statements of the motives rapidly shortens in hypermeasure 4, mirroring the initial rhythmic shortening of motive 2. Hypermeasure 4 is also truncated, consisting of only 3 measures. This seems to be because Hermia and Lysander sing together, instead of the prior call and response, making the third measure of the model redundant. While the motive and hypermeter separate, the phrasing follows the hypermeter through the extensions and truncations, making this both in-phase and metrically ambiguous.

In terms of grouping, the harmonic rhythm largely changes at the halfway point in each hypermetric unit but increases following the rhythmic diminution at rehearsal mark 32. Despite the overt triads, their status as tonal markers is weakened by being often in second inversion, and the lack of tonal function creates a floating triadic post-tonality that does not settle in a home key, likely reflecting the lack of resolution of the lovers in the plot at this point in the opera. In fact, as shown in Figure 8c, all twelve major triads are used beginning with Ab, before finally resting on C major.21See Cooke’s discussion of this (1999, pp. 139–140). This further reinforces the twelve-tone collections found throughout the opera.

Figure 8a: “I swear to thee,” Hermia and Lysander, Act I (Britten 1960, pp. 28–31). 22Recording: Benjamin Britten. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Benjamin Britten. Decca, 1967, CD, https://youtu.be/AlHyOpHc-_Y?si=Om3VNA3IGZ3zg9gz&t=155 © 1960 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. © Renewed 1988 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reproduced with permission from Boosey & Hawkes.

Figure 8b: Motive 1 and Motive 2.

Figure 8c: Metric and harmonic reduction (6:1).

The Rustics

Still within the world of the mortals are the rustics, the troupe of actors led by Bottom who are preparing a play for the Duke of Athens and his wife, Hippolyta. This “play within a play” is a comic reworking of a story from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, where two lovers, Pyramus and Thisbe, are separated by a wall. Shakespeare’s setting is comically egalitarian, with the lion, as well as an anthropomorphized moon and wall, all having sizeable contributions. Britten transforms Shakespeare’s “play within a play” into an “opera within an opera,” with a number of arioso passages parodying Italian opera, adding to the patchwork of influences creating a pasticcio. This “play within an opera” alludes to Ruggero Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci (1892), albeit with a lighter ending. The bombastic buffoonery of the rustics is musically represented by the dotted rhythms, playful syncopation, slapstick tropes, and interrupting isochrony. Importantly, metric regularity and tonality are used parodically in the play and provide a striking contrast to the ethereal soundworld of the fairies. As discussed below, a clear hypermetric model is set up and then interrupted, showing how this comedic aspect percolates through to the depths of hypermeter.

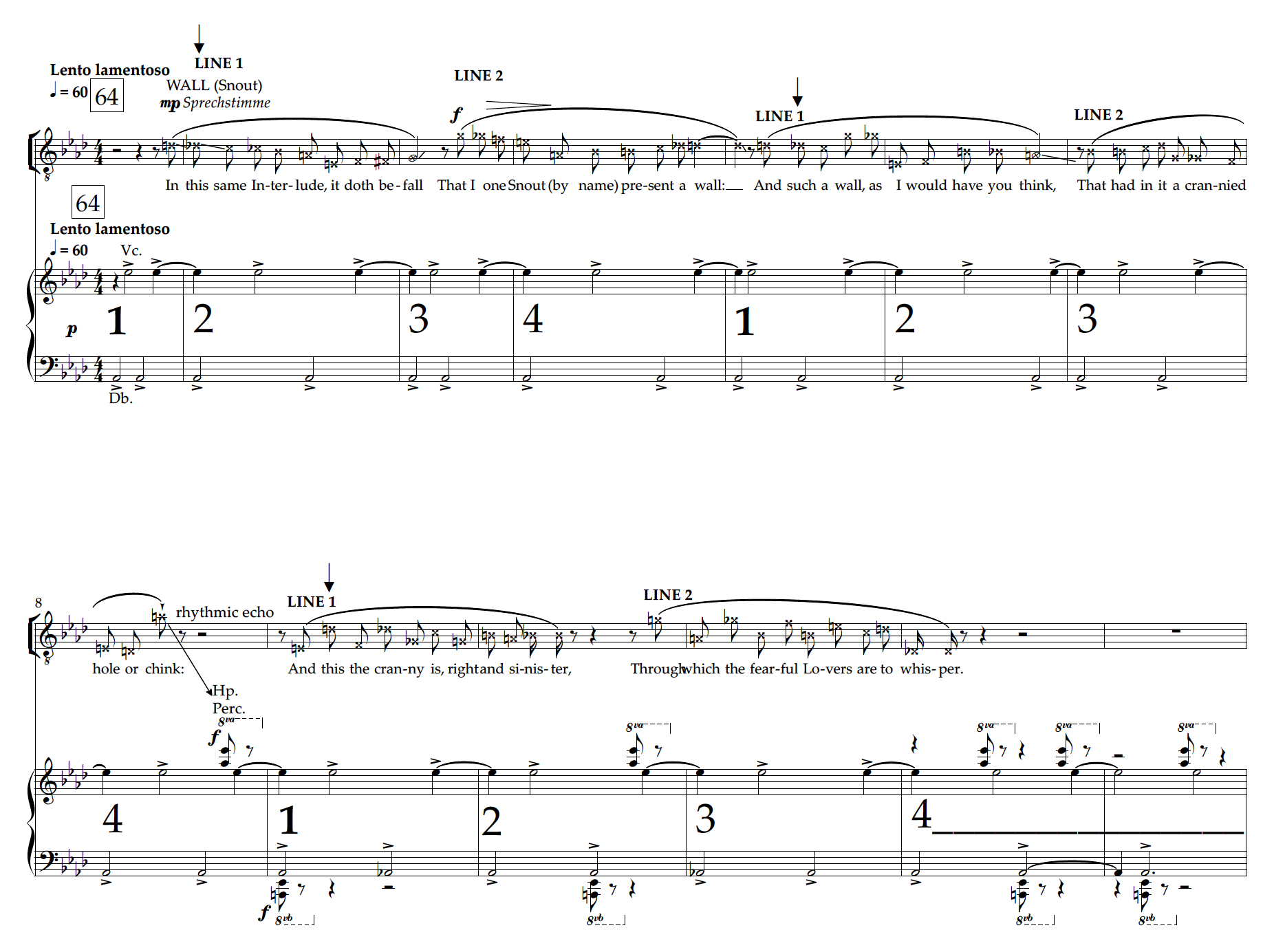

The play opens with Wall’s introductory interlude as a kind of Schoenbergian Sprechstimme, suggesting a rather wobbly wall. As with Figures 1–3, hypermeter is again derived from the iambic pentameter of Shakespeare’s text, every two verses (or couplet) comprising a four-measure hypermeasure, as illustrated in Figure 9. The accompaniment has a parodically regular 4/4 meter with alternating primitivist open fifths in the very low double bass and extremely high cello, creating harmonic stasis. The misalignment of the phrases and hypermeter adds to the wobbliness of the wall, especially as the phrases begin unpredictably on different beats of the 4/4 meter. Another comic effect is the word-painting in the orchestration, notably the rhythmic echo between Wall’s “chink” and the offbeat echo in the harp and percussion (m. 8).

Figure 9: The introduction of Wall, Act III (Britten 1960, pp. 271–272).23Recording: Benjamin Britten. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Benjamin Britten. Decca, 1967, CD, https://youtu.be/qP99F-Mbx0s?si=RwOPav45pcP2k062 © 1960 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. © Renewed 1988 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reproduced with permission from Boosey & Hawkes.

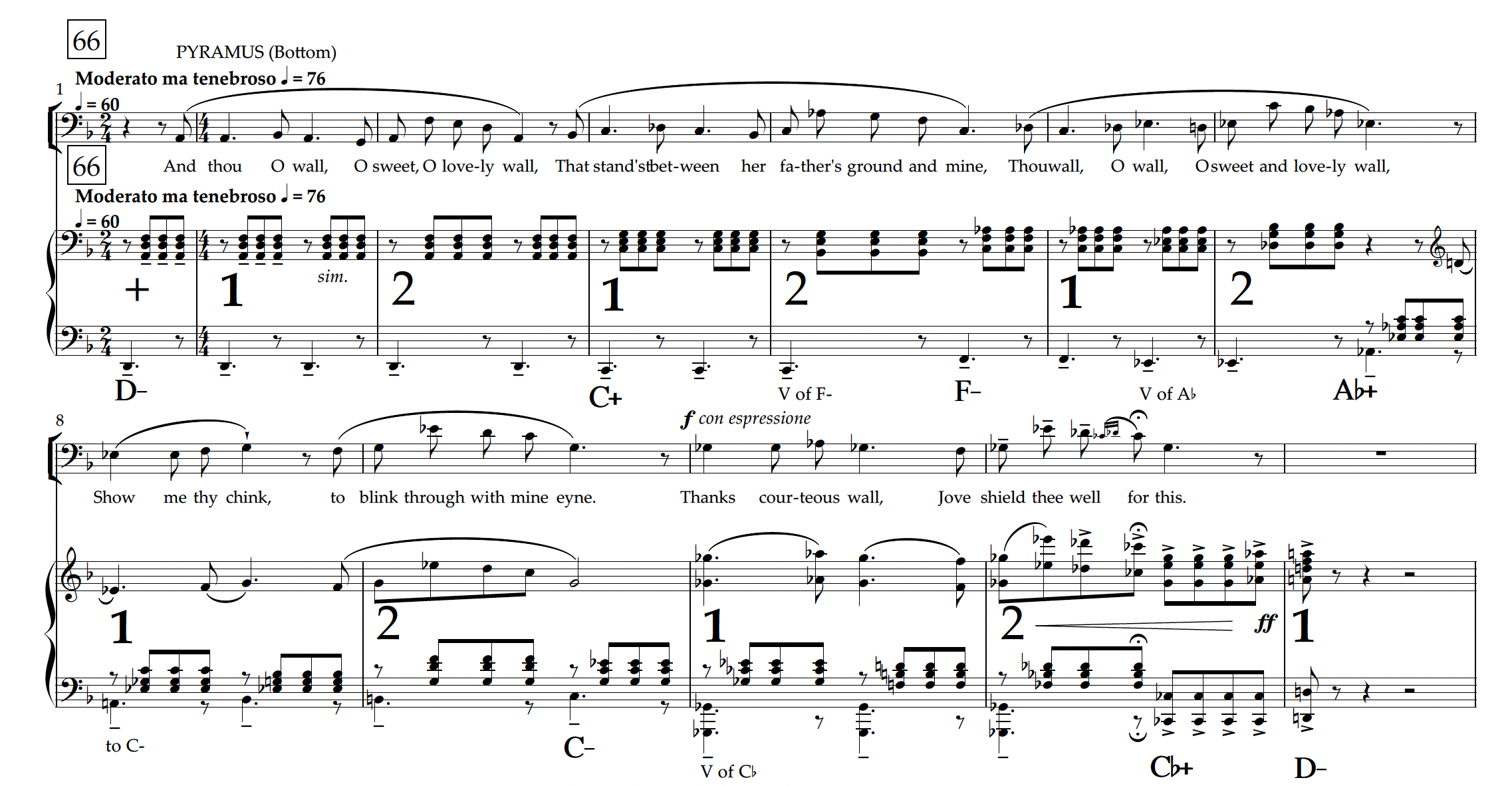

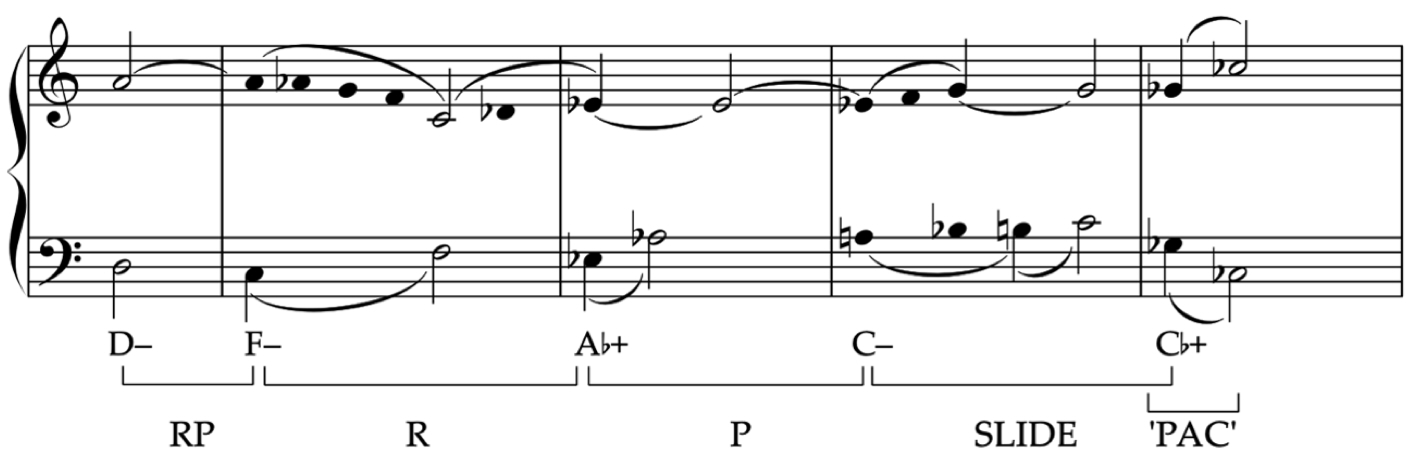

In addition to the buffoonery of the rustics, there are also two pseudo-serious arioso passages parodying Italian opera. Both are metrically interesting by being steady and square in stark contrast to much of the opera.24The other example, not discussed in this article, is “These lily lips, this cherry nose…” at rehearsal mark 84 (Britten 1960, pp. 294–295). Britten sets Pyramus’ immured lament “And thou O wall” as a recitative, followed by a short arioso at rehearsal mark 66 (Figure 10a). The meter is at first ambiguous in the recitative, before coalescing into a two-measure hypermeter to commence the arioso in the style of an Italian aria. In terms of the minor tonality, low register and low 5̂-6̂-5̂ motive, it is reminiscent of the aria “Studia il passo” (Banco’s aria) from Verdi’s similarly Shakespearean Macbeth (1847). What is most notable in Figure 10a is not the regular, stable hypermeter, but the accompanying triads that are almost functionally tonal (without a clear tonic), shifting up in thirds from D minor with applied dominants, leading to C minor followed by a perfect authentic cadence in Cb major. This elevates these hypermetric units to “phrase” status due to the clear tonal motion (shown in Figure 10b).25In Rothstein’s definition of a phrase, “if there is not tonal motion, there is no phrase” (1989, p. 5). The meter remains regular in this arioso, and there are no manipulations as in the other examples. The phrases are shifted out-of-phase, allowing for an upbeat, while remaining metrically clear, as is typical of a Verdian aria.

Figure 10a: “And thou O wall…,” Bottom, Act III (Britten 1960, pp. 274–275).26Recording: Benjamin Britten. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Benjamin Britten. Decca, 1967, CD, https://youtu.be/B3LVIjiumrs?si=eV063Fy0j8wOn-df&t=30 © 1960 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. © Renewed 1988 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reproduced with permission from Boosey & Hawkes

Figure 10b: Harmonic reduction (with neo-Riemannian transformations to show movement by thirds).27These neo-Riemannian transformations that illustrate parsimonious chromatic movements between triads were first introduced by David Lewin ([1987]2007) and later codified by Richard Cohn (2012). P = “parallel” is where the quality of the chordal third is switched from major to minor (e.g. C major and C minor); R = “relative” is where the triad changes between its relative major or minor (e.g. C major and A minor); SLIDE is the preservation of the third while the root and fifth both move up or down a semitone (e.g. C major and C# minor).

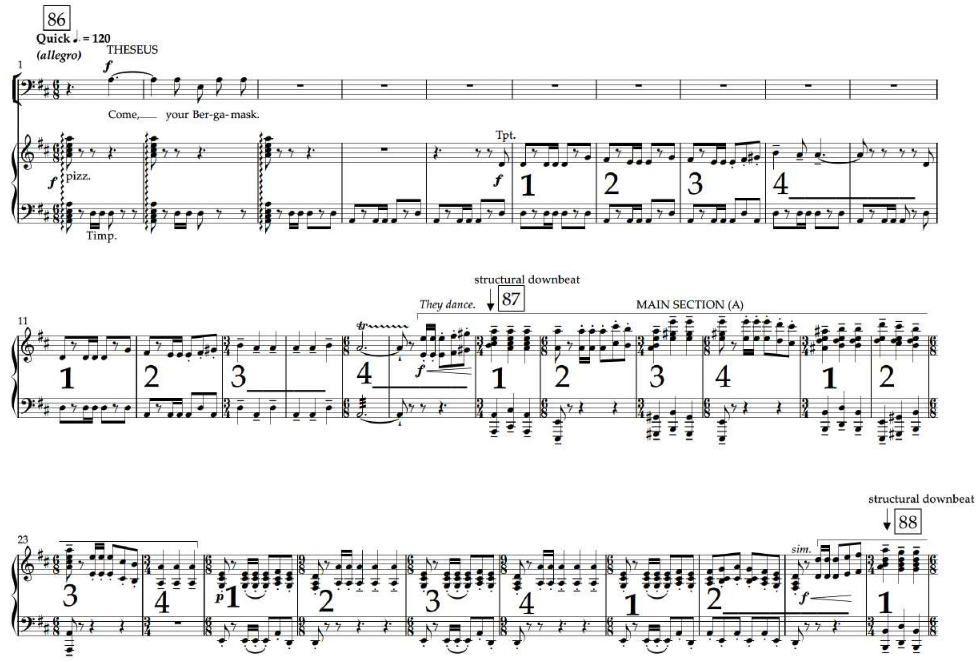

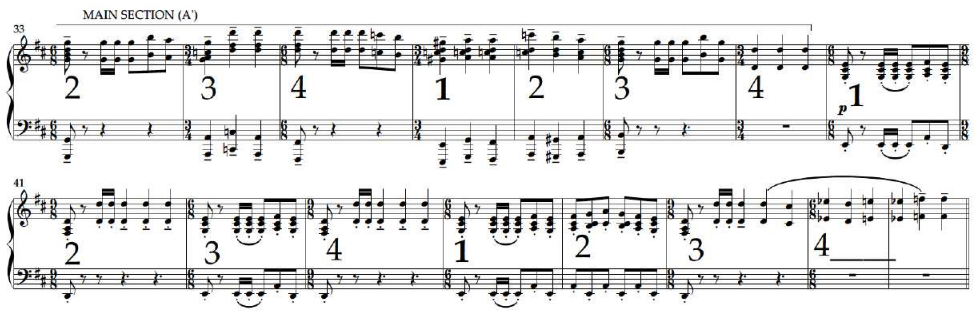

Hypermetric extension can be used to add to the buffoonery of the rustics, as in Britten’s realization of Shakespeare’s “Bergamask” dance that occurs just after the conclusion of the play, as the finale for the mortals (Figure 11). The opening 6/8 meter feels like an Italian tarantella before becoming hemiolic at rehearsal mark 87. The alternation between 6/8 and 3/4 conjures up the hemiolic hedonism of Gilbert and Sullivan, such as the finales of Patience (1881) or The Gondoliers (1891). The dance is most clearly pronounced at rehearsal marks 87 and 88, each having a structural downbeat, and labelled A and A’. There is a four-measure hypermeasure that emerges 11 measures before rehearsal mark 87. Four measures before rehearsal mark 87 is a metric augmentation that serves as a written rallentando in preparation for the dance.28This parallels Rothstein’s concept of “expansion by composed-out deceleration” (1989, pp. 80–81). One notable manipulation is the addition of 9/8 measures after each A section. The addition of an extra beat interrupts the otherwise regular meter and hypermeter, a prime example of metric play. This adds a comic air of ambiguity, showing the goofiness of the rustics as they return to reality.

Figure 11: “Bergamask” dance, Act III (Britten 1960, pp. 297–298).29Note that Britten does not distinguish between 3/4 and 6/8 in the score, writing “3/4 6/8” as the time signature. For this analysis I have written them in for clarity. Recording: Benjamin Britten. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Benjamin Britten. Decca, 1967, CD, https://youtu.be/x47UFN_kF4E?si=NzyTHolOhZLJu0S4, © 1960 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. © Renewed 1988 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reproduced with permission from Boosey & Hawkes.

Conclusion

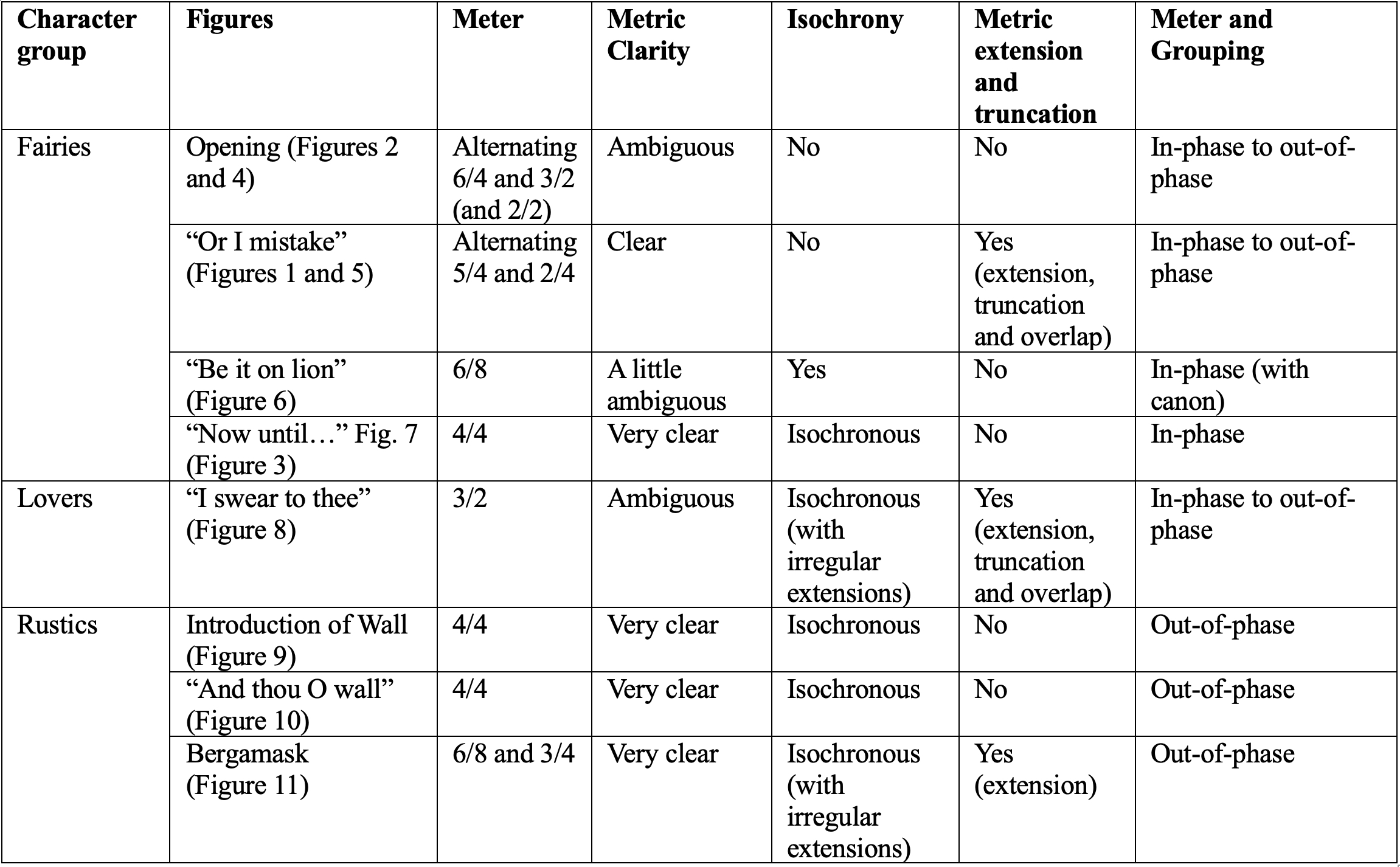

This article has illustrated some of the idiosyncratic ways in which meter and hypermeter are constructed and manipulated in Benjamin Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. In particular, the diverse array of metric types and techniques is well suited to the three character groups and the opera’s episodic form (see the summary in Figure 12). These techniques allow Britten to playfully develop and form the metric structures. Several pertinent observations emerge from the analysis. First, many of Britten’s meters respond to the poetic meters of Shakespeare’s text, which are then used to generate larger hypermetric units, linking hypermeter to the text. Second, each of the three character groups (fairies, lovers, and rustics) possesses a distinct musical identity created by musical tendencies observed in select examples—including a metric one. The fairies are typified by ambiguity and irregularity, notably in the use of non-isochronous hypermeter. The mortals have more regularity; the lovers retain a sense of ambiguity by featuring metric extensions that create a dreamy feel and the rustics are often comically regular, typified by hypermetric models that are abruptly interrupted. Third, Britten frequently manipulates and transforms the metric structures. For example, he often begins a section with a regular hypermetric model before manipulating it and deviating from it through a range of techniques, including hypermetric extension, truncation and overlap. These transformations allow for the hypermeter to reflect the text, creating ambiguity or interruption at key moments. Fourth, meter frequently interacts with other musical parameters, especially grouping. There is a general trend of passages shifting between in-phase and out-of-phase. Fifth, there is little metric dissonance in the work (as shown in Figure 12), with most of the various layers being metrically consonant. This is in contrast to many of Britten’s earlier works, as discussed in Duncan (2017a, 2017b). Lastly, there is little evidence of a large-scale hypermetric pattern governing this work; instead it appears that the form is created through the patterning of a number of discrete episodes, aligning with the studies of Cooke (1993, 1999). To conclude, Britten creatively employs a range of metric devices as part of the stylistic mosaic, which together capture the essence of Shakespeare’s play, allowing for “time” to be “dreamt away.”30“Dream away the time” is a quote from Act 1, Scene 1, Hippolyta, line 8 (of Shakespeare’s original play). An earlier version was presented at “Rhythm in Music Since 1900” conference at McGill University in Montréal in September 2023. I am grateful to the editors, the anonymous reviewers, as well as Nicole Biamonte, Daphne Leong, Christoph Neidhöfer and Lloyd Whitesell for their generous advice and feedback. All the musical examples are reproduced with generous permission from Boosey & Hawkes (for all) and the British Library Board (for specifically Figures 4c, 4d, and 4e). In particular, I thank Chris Scobie at the British Library and Nicholas Clark at the Britten Pears … Continue reading

Figure 12: Summary of metric types and techniques in the Figures.

Bibliography

Brett, Philip (1993), “Britten’s Dream,” Ruth A. Solie (ed.), Musicology and Difference. Gender and Sexuality in Music Scholarship, Berkeley CA, University of California Press, pp. 259–280.

Britten, Benjamin ([1960]1961), A Midsummer Night’s Dream [Full score], London, Boosey and Hawkes.

——— (1960), A Midsummer Night’s Dream [Vocal score], London, Boosey and Hawkes.

——— (ca. 1960), Discarded material for A Midsummer Night’s Dream (sketches), BBM/a_midsummer_nights_dream/2/2, Aldeburgh, Britten Pears Arts Archive.

Brodsky, Seth (2016), “Remembering, Repeating, Passacaglia. Weak Britten,” Acta Musicologica, vol. 88, n° 2, pp. 165–192.

Cohn, Richard (2023), “Graphing Deep Hypermeter in the Scherzo Movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony,” Music Theory Spectrum, vol. 45, n° 2, pp. 99–217.

——— (2012), Audacious Euphony. Chromatic Harmony and the Triad’s Second Nature, New York, Oxford University Press.

——— (1992), “The Dramatization of Hypermetric Conflicts in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony,” 19th-Century Music, vol. 15, n° 3, pp. 188–206.

Cone, Edward T. (1968), Musical Form and Musical Performance, New York, Norton.

Cooke, Mervyn (1993), “Britten and Shakespeare. Dramatic and Musical Cohesion in A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” Music & Letters, vol. 74, n° 2, pp. 246–268.

——— (1999), “Britten and Shakespeare. A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” in Mervyn Cooke (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Benjamin Britten, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, pp. 129–146.

Duncan, Stuart Paul (2017a), “Priming Meter and Metric Conflict in Britten’s Early Vocal Music 1943–1946,” in David Forrest et al. (eds.), Essays on Benjamin Britten from a Centenary Symposium, Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 77–112.

——— (2017b), Metric Experiments in Benjamin Britten’s Vocal Music. 1943–1945, PhD diss., Yale University.

Forrest, David (2010), “Prolongation in the Choral Music of Benjamin Britten,” Music Theory Spectrum, vol. 32, n° 1, pp. 1–25.

Kildea, Paul (2003), Britten on Music, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Krebs, Harald (1999), Fantasy Pieces. Metrical Dissonance in the Music of Robert Schumann, New York, Oxford University Press.

Leccia, Marinu (2024), Playful Aesthetics in the Music of Benjamin Britten, PhD diss., University of Oxford.

Lerdahl, Fred, and Ray Jackendoff (1983), A Generative Theory of Tonal Music, Cambridge MA, MIT Press.

Lewin, David ([1987]2007), Generalized Musical Intervals and Transformations, New York, Oxford University Press.

London, Justin (2012), Hearing in Time. Psychological Aspects of Musical Meter, New York, Oxford University Press.

Mark, Christopher (1985), “Contextually Transformed Tonality in Britten,” Music Analysis, vol. 4, n 3, pp. 265–287.

Roseberry, Eric (1963), “A Note on the Four Chords in Act II of A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” Tempo, vol. 66–67, pp. 36–37.

Rothstein, William (1989), Phrase Rhythm in Tonal Music, New York, Schirmer.

Rupprecht, Philip, (1996), “Tonal Stratification and Uncertainty in Britten’s Music,” Journal of Music Theory, vol. 40, n° 2, pp. 311–346.

——— (2001), The Musical Language of Benjamin Britten, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

——— (2017), “Quickenings of the Heart. Notes on Rhythm and Tempo in Britten,” in Vicki P. Stroeher and Justin Vickers (eds.), Benjamin Britten Studies. Essays on an Inexplicit Art, Woodbridge, Boydell Press, pp. 317–345.

Shakespeare, William ([1595]2007), “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” Jonathan Bate and Eric Rasmussen (eds.), The Royal Shakespeare Company Shakespeare Complete Works, Houndmills, Macmillan, pp. 365–412.

Sullivan, James (2021), “Metric Manipulations in Post-Tonal Music,” Music Theory Spectrum, vol. 43, n° 1, pp. 123–152.

Temperley, David (2008), “Hypermetrical Transitions,” Music Theory Spectrum, vol. 30, n° 2, pp. 305–325.

Whittall, Arnold (1990), The Music of Britten and Tippet. Studies in Themes and Techniques, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

——— (1992), “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” in Stanley Sadie (ed.), The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, London, Macmillan, pp. 179–181.

Wintle, Christopher (2006), All the Gods. Benjamin Britten’s “Night-Piece” in Context, London, Plumbago.

| RMO_vol.12.2_McGartland |

Attention : le logiciel Aperçu (preview) ne permet pas la lecture des fichiers sonores intégrés dans les fichiers pdf.

Citation

- Référence papier (pdf)

Aidan McGartland, « Dream Away the Time”. Metric Play in Benjamin Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream », Revue musicale OICRM, vol. 12, no 2, 2025, p. 106-129.

- Référence électronique

Aidan McGartland, « Dream Away the Time”. Metric Play in Benjamin Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream », Revue musicale OICRM, vol. 12, no 2, 2025, mis en ligne le 11 décembre 2025, https://revuemusicaleoicrm.org/rmo-vol12-n2/metric-play-Britten/, consulté le…

Auteur

Aidan McGartland, McGill University

Aidan McGartland is doctoral candidate in music theory at McGill University, where he focusses on the works of Elisabeth Lutyens, Margaret Sutherland and Benjamin Britten. He holds degrees in classical voice and musicology from the University of Melbourne, and a Master of Studies in musicology from the University of Oxford. In 2023, Aidan was awarded a prestigious Australian postgraduate scholarship from the Ramsay Centre. Aidan has previously presented for the Society for Music Analysis, the Musicological Society of Australia, and the Society for Music Theory. He has forthcoming analytical publications on works by Margaret Sutherland, Benjamin Britten and Igor Stravinsky.

Notes

| ↵1 | A thorough search through all the sketches, discarded material, and plans uncovered little on meter. |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | See for example: David Forrest (2010), Christopher Mark (1985), Philip Rupprecht (2001), and Christopher Wintle (2006). |

| ↵3 | Krebs defines grouping dissonances as a type of metric dissonance, involving at least two pulse layers whose interpulse durations are not multiples or factors of one another (e.g., a half-note pulse versus a dotted-half-note pulse) (1999, pp. 31–32). |

| ↵4 | Justin London writes that “conversely, the upper limit is around 5 to 6 seconds, a limit set by our capacities to hierarchically integrate successive events into a stable pattern” (2012, p. 27). |

| ↵5 | Note that Britten does not distinguish between 5/4 and 2/4 in the score, writing “5/4 2/4” as the time signature. For this analysis I have written them both in for clarity. Dynamics and articulation have been largely removed from the following examples. © 1960 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. © Renewed 1988 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reproduced with permission from Boosey & Hawkes. |

| ↵6 | Originally not the opening of the play but reordered by Pears and Britten. |

| ↵7 | © 1960 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. © Renewed 1988 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reproduced with permission from Boosey & Hawkes. |

| ↵8 | © 1960 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. © Renewed 1988 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reproduced with permission from Boosey & Hawkes. |

| ↵9 | This large 5 x 2 hypermeasure is too slow to be perceived as meter per se, and is purely an abstract device (see London 2012, p. 27). |

| ↵10 | Note Britten’s twelve-tone checklists in the margins, ensuring that all twelve major triads have been covered |

| ↵11 | Recording: Benjamin Britten. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Benjamin Britten. Decca, 1967, CD, https://youtu.be/QRfR-nvI8Uo?si=yrriDaZ1_AYobHiS © 1960 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. © Renewed 1988 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reproduced with permission from Boosey & Hawkes. |

| ↵12 | © Britten Pears Arts (brittenpears.org). |

| ↵13 | © Britten Pears Arts (brittenpears.org). |

| ↵14 | © Britten Pears Arts (brittenpears.org). |

| ↵15 | Recording: Benjamin Britten. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Benjamin Britten. Decca, 1967, CD, https://youtu.be/QRfR-nvI8Uo?si=9w93fUGMfGVgeoE1&t=167 © 1960 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. © Renewed 1988 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reproduced with permission from Boosey & Hawkes. |

| ↵16 | Oberon’s leitmotif is created by three chromatically adjacent minor thirds (see m. 5 of Figure 6). The consequent of mm. 7–8 is related by an I7 transformation. |

| ↵17 | This canon resembles what James Sullivan discusses as “close imitation” (2021). The only difference is that this is spaced out, making it less close (and it abruptly stops), but it is ultimately rooted in the same technique of imitation. |

| ↵18 | Recording: Benjamin Britten. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Benjamin Britten. Decca, 1967, CD. https://youtu.be/b-NFjXtAT-4?si=dwgX0vwvaNny8fP0 © 1960 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. © Renewed 1988 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reproduced with permission from Boosey & Hawkes. |

| ↵19 | This structure is what Richard Cohn would call “pure duple” as each of the six metric levels is duple (1992, 194). |

| ↵20 | Recording: Benjamin Britten. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Benjamin Britten. Decca, 1967, CD, https://youtu.be/hSCH-DTlpXk?si=X8ygyxrAG2JD6PuX&t=120 © 1960 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. © Renewed 1988 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reproduced with permission from Boosey & Hawkes. |

| ↵21 | See Cooke’s discussion of this (1999, pp. 139–140). |

| ↵22 | Recording: Benjamin Britten. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Benjamin Britten. Decca, 1967, CD, https://youtu.be/AlHyOpHc-_Y?si=Om3VNA3IGZ3zg9gz&t=155 © 1960 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. © Renewed 1988 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reproduced with permission from Boosey & Hawkes. |

| ↵23 | Recording: Benjamin Britten. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Benjamin Britten. Decca, 1967, CD, https://youtu.be/qP99F-Mbx0s?si=RwOPav45pcP2k062 © 1960 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. © Renewed 1988 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reproduced with permission from Boosey & Hawkes. |

| ↵24 | The other example, not discussed in this article, is “These lily lips, this cherry nose…” at rehearsal mark 84 (Britten 1960, pp. 294–295). |

| ↵25 | In Rothstein’s definition of a phrase, “if there is not tonal motion, there is no phrase” (1989, p. 5). |

| ↵26 | Recording: Benjamin Britten. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Benjamin Britten. Decca, 1967, CD, https://youtu.be/B3LVIjiumrs?si=eV063Fy0j8wOn-df&t=30 © 1960 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. © Renewed 1988 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reproduced with permission from Boosey & Hawkes |

| ↵27 | These neo-Riemannian transformations that illustrate parsimonious chromatic movements between triads were first introduced by David Lewin ([1987]2007) and later codified by Richard Cohn (2012). P = “parallel” is where the quality of the chordal third is switched from major to minor (e.g. C major and C minor); R = “relative” is where the triad changes between its relative major or minor (e.g. C major and A minor); SLIDE is the preservation of the third while the root and fifth both move up or down a semitone (e.g. C major and C# minor). |

| ↵28 | This parallels Rothstein’s concept of “expansion by composed-out deceleration” (1989, pp. 80–81). |

| ↵29 | Note that Britten does not distinguish between 3/4 and 6/8 in the score, writing “3/4 6/8” as the time signature. For this analysis I have written them in for clarity. Recording: Benjamin Britten. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Benjamin Britten. Decca, 1967, CD, https://youtu.be/x47UFN_kF4E?si=NzyTHolOhZLJu0S4, © 1960 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. © Renewed 1988 by Hawkes & Son (London) Ltd. Reproduced with permission from Boosey & Hawkes. |

| ↵30 | “Dream away the time” is a quote from Act 1, Scene 1, Hippolyta, line 8 (of Shakespeare’s original play). An earlier version was presented at “Rhythm in Music Since 1900” conference at McGill University in Montréal in September 2023. I am grateful to the editors, the anonymous reviewers, as well as Nicole Biamonte, Daphne Leong, Christoph Neidhöfer and Lloyd Whitesell for their generous advice and feedback. All the musical examples are reproduced with generous permission from Boosey & Hawkes (for all) and the British Library Board (for specifically Figures 4c, 4d, and 4e). In particular, I thank Chris Scobie at the British Library and Nicholas Clark at the Britten Pears Arts archive for their assistance in sourcing materials. |