Paradigmatic Analysis and the Performance of Xenakis’s Solo Percussion Music

Fabrice Marandola

| PDF | CITATION | AUTHOR |

Abstract

This article explores the application of paradigmatic analysis as a practical tool for performers to deepen their understanding and interpretation of Iannis Xenakis’s solo percussion works, particularly Psappha (1975) and Rebonds (1987-1989). Drawing from personal experience and analytical methods developed by Nicolas Ruwet and Simha Arom, I demonstrate how segmenting musical material based on repetition and marks such as accentuation, timbre, and durations can enhance the learning process and inform interpretative decisions. The study emphasizes the value of performer-driven analysis in navigating Xenakis’s complex rhythmic and structural designs. Through detailed examples, I illustrate how paradigmatic analysis can reveal underlying patterns, support memory retention, and inspire creative performance strategies. Ultimately, I advocate for a flexible, evolving analytical practice that aligns with the interpretive needs of musicians engaging with contemporary percussion repertoire

Keywords: Iannis Xenakis; paradigmatic analysis; percussion; performance; Psappha; Rebonds.

Résumé

Cet article propose aux interprètes d’utiliser l’analyse paradigmatique comme outil pratique permettant d’approfondir la compréhension et l’interprétation des œuvres pour percussion solo de Iannis Xenakis, Psappha (1975) et Rebonds (1987-1989). M’appuyant sur mon expérience personnelle et sur les méthodes analytiques développées par Nicolas Ruwet et Simha Arom, je démontre comment le fait de segmenter le matériau musical en se fondant sur la répétition et sur des marqueurs tels que l’accentuation, le timbre et les durées, peut améliorer le processus d’apprentissage et alimenter le processus de décision quant aux choix d’interprétation. L’étude souligne l’intérêt d’analyses réalisées du point de vue de l’interprète pour prendre la pleine mesure des conceptions rythmiques et structurelles complexes de Xenakis. À l’aide d’exemples détaillés, j’illustre comment l’analyse paradigmatique peut révéler des structures sous-jacentes, favorisant la mémorisation et menant à des stratégies d’interprétation créatives. L’article vise ainsi à proposer une approche analytique pratique, qui s’adapte aux besoins des artistes engagés dans l’interprétation du répertoire contemporain.

Mots clés : analyse paradigmatique ; Iannis Xenakis ; interprétation ; percussion ; Psappha ; Rebonds.

Preamble

In the summer of 1989, I had the chance to attend the French premiere of Iannis Xenakis’s Rebonds by Sylvio Gualda at the Festival d’Avignon: as a member of the Orchestre des Jeunes de la Méditerranée, a summer orchestral program for young musicians, I was coached by Gualda, who invited the percussion section to this memorable concert dedicated to Xenakis’s music. A few years later, in the spring of 1992, movement “B” of Rebonds was one of the imposed works on the program of my final percussion exam at the Conservatoire National de Région de Paris, and I had to dive into the task of learning the piece in the short amount of time granted to students to learn set pieces (five to six weeks). At the same time, I began attending the seminars of ethnomusicologist Simha Arom and discovering his analytical methods for the study of African music. I did not realize it at the time, but this crossover between analytical approach and performance practice would largely inform the rest of my career, beginning with the intense learning phase that led to my first performance of Rebonds B for that long ago exam.

Introduction

The aim of this article is to provide some insights on my pragmatic use of paradigmatic analysis tools for facilitating my comprehension, learning process, and interpretation of percussion works, taking some examples from the music of Iannis Xenakis. Claude Abromont (Abromont 2021) provides a useful overview of paradigmatic analysis and describes it as being at the crossover of several disciplines such as linguistics, semiology, anthropology and musicology. Applied to musicology, it has been employed to study monodic music, harmonized or not, as well as extra-European, ancient, and contemporary repertoires. In a nutshell, paradigmatic analysis in music is based on the segmentation of a musical work by transcribing it in such a way that similar elements are superimposed to highlight their commonalities and variations. The segmentation is based on a set of rules that must be made explicit, an essential fact, according to Jean-Jacques Nattiez who remarks that the redaction of explicit rules, or of the utilization of these rules, is common to all major works engaging with paradigmatic analysis (Nattiez 2003, p. 46).

After describing how my discovery of Arom’s work immediately influenced my learning process of Rebonds, I will briefly revisit the principles of paradigmatic analysis established by Nicolas Ruwet, as well as how Arom determined a set of marks to facilitate the segmentation of rhythmic sequences. I will then provide examples of my application of paradigmatic analytical principles from the point of view of a performer, which will highlight some differences between an analysis that reveals the concepts used to write a piece and one where the practical outcomes are guided by the necessity to learn, memorize, and perform a piece. Since I have previously written about paradigmatic analysis and Xenakis regarding the movement Peaux from his major percussion sextet Pleiades (Marandola 2012), I will focus here on his solo percussion repertoire, namely Psappha and Rebonds. Written respectively in 1975 and 1987–1989,1The publications dates for Psappha and Rebonds by Éditions Salabert are respectively 1976 and 1987. both works are milestones of the percussion solo repertoire and were premiered by Xenakis’s longtime collaborator, French percussionist Sylvio Gualda.2For more information on Gualda and Xenakis collaboration, see Gualda (2010). Whereas Rebonds has a fixed instrumentation and is notated in standard Western musical notation, Psappha calls for six categories of instruments (named A to F) to be chosen by the interpreter based on the criteria set by the composer in his explanatory note (Xenakis 1976, p. 9), and its notation consists of a grid where each column represents a time unit, from 0 to 2396.

Repetition and marks

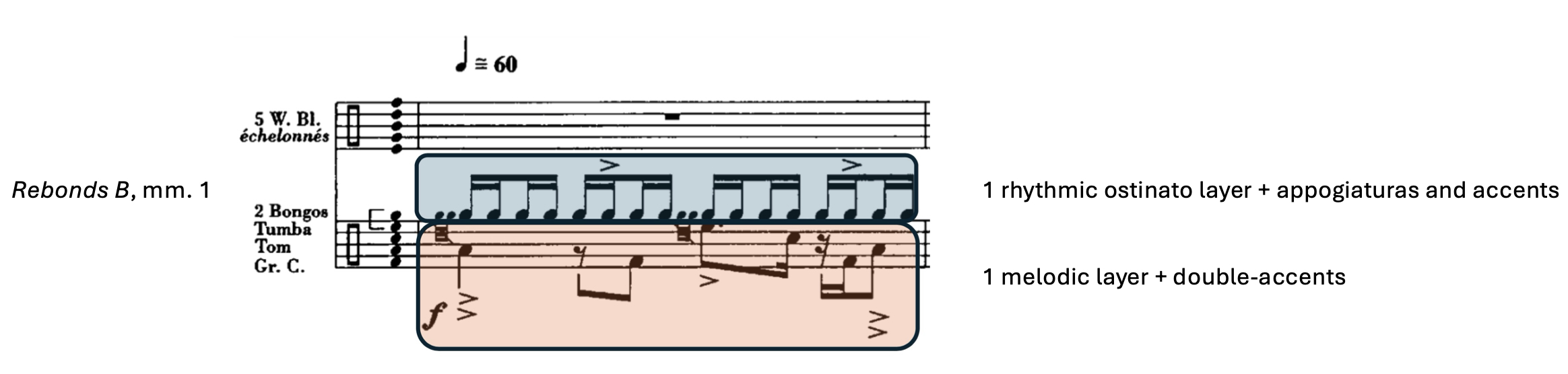

Looking at the opening measures of Rebonds B (Figure 1), one can easily observe that two layers—or voices—coexist: the top layer, played on the highest bongo, consists of an ostinato of sixteenth-notes, embellished by appoggiaturas (drags) and single accents, while the lower layer consists of another ostinato played on five notes distributed on the four remaining drums, beginning with a double-accent. These two layers are often referred to by the practitioners as “rhythmic” for the top one and “melodic” for the lower one, underlining the contrast between the repeated notes on a single drum versus a melodic contour performed on several drums with varied durations.

Figure 1: First bar of Rebonds B3Iannis Xenakis, Rebonds A & B, © 1987 Ed. Salabert. with two layers identified as “rhythmic” and “melodic”.

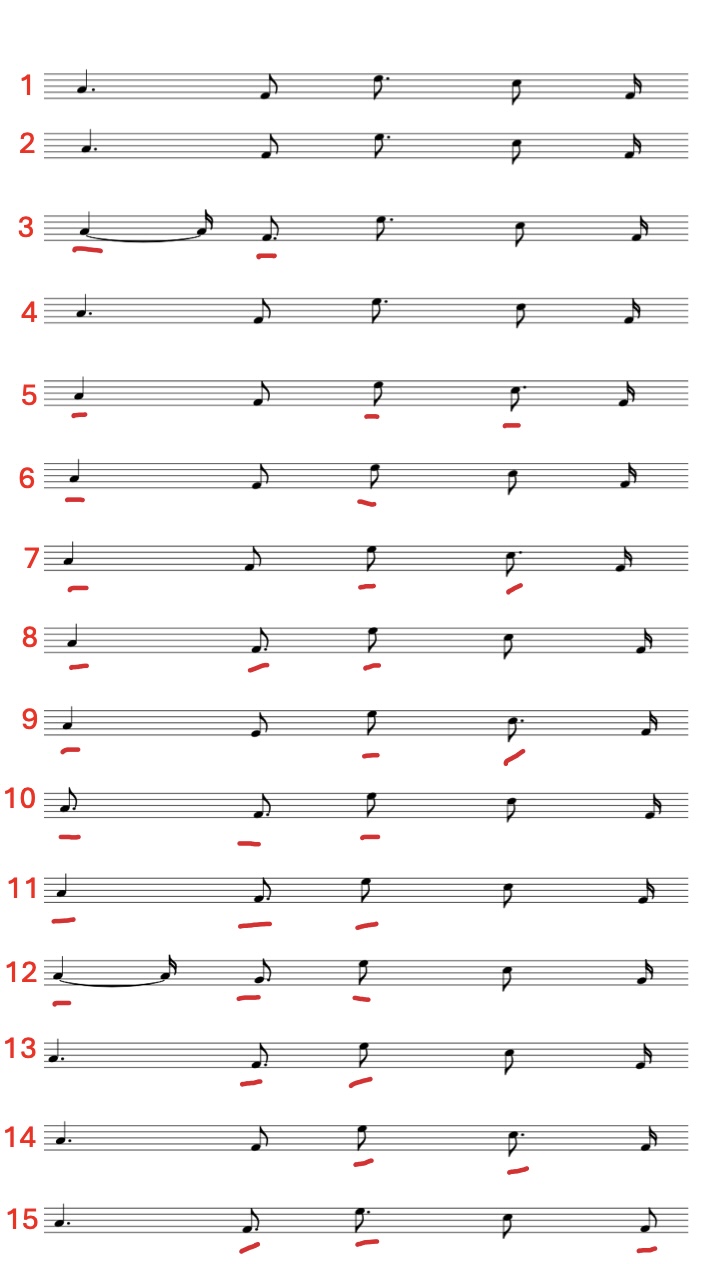

Taking another look at the score, it also quickly becomes apparent that both layers will undergo progressive and constant transformations, whose natures tend to be totally independent of the meter of the piece (4/4): as in many other pieces by Xenakis, the 4/4 metric indication is merely a commodity to provide an easy frame of reference for the interpreter. In 1992, fresh from my recent discovery of Arom’s methods of paradigmatic analysis, I made my first paradigmatic transcription of the beginning of Rebonds B in order to better understand the nature of the transformations that were taking place in the melodic layer, and how this new way of looking at the musical material might change my perception of the phrasing of the piece when combining the two layers (Figure 2). I started by identifying the beginning of each cycle in the score, before transcribing the score according to Nicolas Ruwet’s principles, themselves inspired by Claude Lévi-Strauss (Ruwet 1966, p. 76), i.e. superposing elements that were similar, starting a new line for each cycle. In this case, I would use the melodic cycle as the reference, which would highlight the variations of their durations from one cycle to the next. I also applied Arom’s method to distinguish between metrical and rhythmical notation; in the metrical notation, all durations are notated in relation to the subdivision in beats and bars, whereas a rhythmical notation “would represent each duration by a single sign, independently of whether it crosses from one pulsation to another” (Arom 1991, p. 228). Figure 2a presents the original score with red marks that correspond to the beginning of each cycle. In Figure 2b (paradigmatic transcription using rhythmic notation), durations that are different from the first occurrence of the cycle (top line) are underlined in red.

Figure 2a: First 12 bars of Rebonds B. Original score with segmentation of the “melodic” cycle.

Figure 2b: First 12 bars of Rebonds B. Paradigmatic transcription using rhythmic notation of the 15 first occurrences of the “melodic” cycle, where duration variants are underlined in red.

Before going further and looking at more complex examples, it is useful to briefly revisit a few principles regarding paradigmatic analysis and segmentation. Ruwet’s analytical approach focuses on being able to establish clear criteria to proceed to the analysis of any musical work, prompting analysts to be explicit when it comes to segmentation: “the crucial question, first and foremost, is the following: What are the criteria which, in such and such case, have presided over the segmentation?” (Ruwet 1987, p. 14). Referring to Gilbert Rouget’s work (Rouget 1961, p. 41), Ruwet sets repetition as the main element that will permit the segmentation of a work, and he recommends identifying “the longest possible [segments] which are repeated in their entirety, either immediately after their first statement or after other intervening segments” (Ruwet 1987, p. 18). Arom further clarifies this approach by referring to two principles, repetition and commutation, as key analytical concepts:

One will use, on the one hand, the repetition principle with which one can define, on the musical continuum, identical configurations, and, on the other hand, the commutation principle with which one can make out configurations similar to each other and which can be substituted for one another on condition that they be—on one plane at least—equivalent as regards the cultural judgement of identity.

Repetition and commutation are two principles which the analysis can rest on. (Arom 1981, p. 46)

Commutation refers to the elements that are similar enough to be considered variants of one another: “By definition, the members of a paradigm must have some common feature and one or more differences” (Arom 1993, p. 20).

In response to Ruwet’s recommendations to establish explicit segmentation criteria, Arom clearly defines three types of marks that can be used to segment any rhythmic sequence:

If a sequence of percussions is to be accounted a rhythmic figure, at least one of its constituents must be marked. There are three kinds of marks—accentuation, tone colour alternation and contrasting durations—one of which will be used to break down figures into their constituent parts. (Arom 1989, p. 93)

It should be noted that tone colour can also refer to pitch, but Arom wanted to make sure to encapsulate timbral differences in his definition.

Using this definition of marks and looking back at the first bars of Rebonds B, at least three potential marks can be identified (Figure 3): on the top layer, the appoggiaturas (drags) that can be viewed as timbral change (tone colour) and the single accents, and on the lower layer, the double accents that also correspond to the beginning of the melodic pattern (tone colour/pitch change). My first approach focused on the melodic cycle as primary criterion for segmentation, but it would be possible to proceed to a segmentation that would prioritize another mark, for example the appoggiaturas. In practice, this movement proceeds with three levels of periodicities that are each based on a different mark (appoggiatura, single accent on the top bongo, melodic cycle) that constantly shift in relation to each other.

Figure 3: Rebonds B, mm. 1-4, potential marks to be used for segmentation.

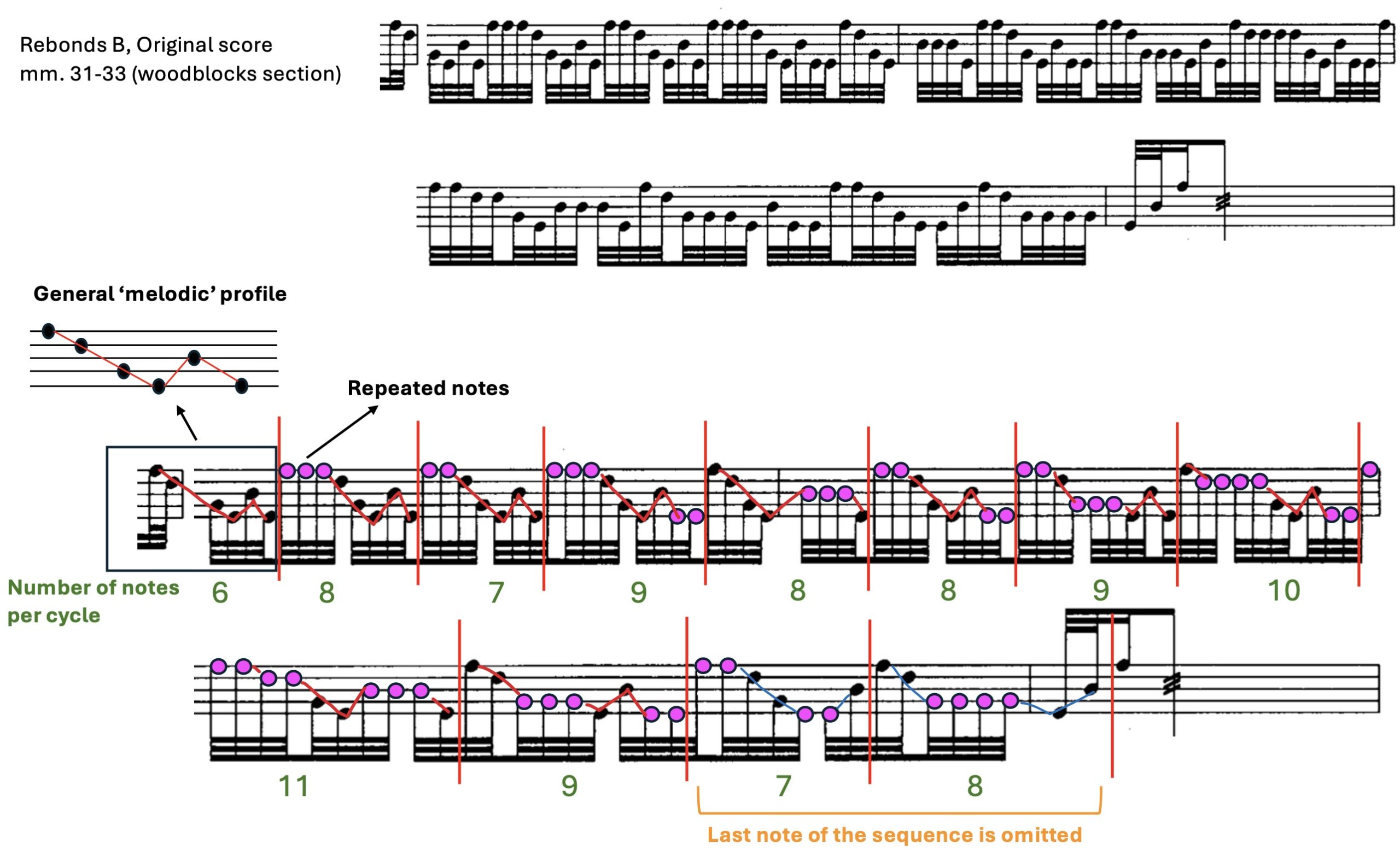

The primacy of the melodic contour through rhythmic variations, which I identified in Pleiades (Marandola 2012), is obvious in other sections of Rebonds. In the first woodblock section of Rebonds B for example, a melodic cycle of six notes is repeated with duration variations for different notes, with the two last occurrences being shortened by one note of the melodic cycle (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Rebonds B, mm 31-33 (woodblocks), original score and transcription of its segmentation based on a melodic cycle of six notes, whose variants consist of the repetition of certain notes in the cycle; the two last melodic cycles are shortened by one note.

Being able to identify this kind of structure is extremely helpful, since delineating a segmentation in which inherent logic is based on the structure of the piece fast-forwards the learning process: confronted with what seems a quasi-random pattern, performers tend to default to metric subdivisions to segment such a passage into smaller units that can be more easily rehearsed and assimilated. Once recurrences are identified, the new grouping allows the performer to focus mostly on what differs from one group to the next, while providing a unifying framework, facilitating the learning process in two ways. The segmentation based on the paradigmatic analysis also offers new insights regarding the interpretation of the piece, offering potential phrasing possibilities.

Permutations

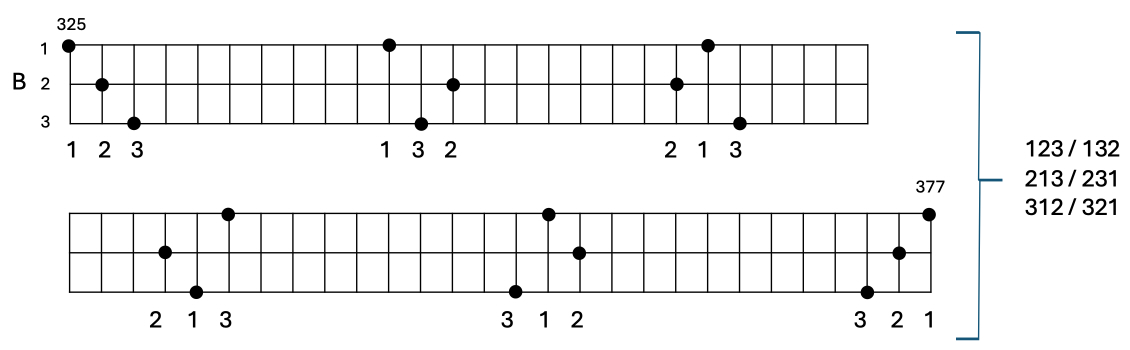

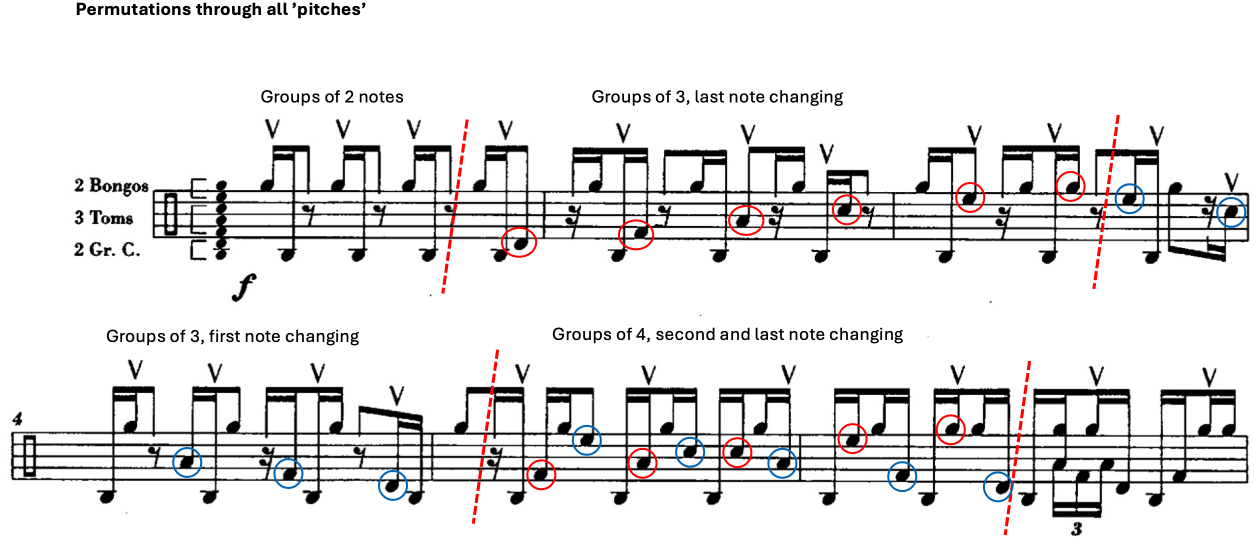

Xenakis uses another process, which is based on the exploration of systematic permutation of pitches within a set group of notes:4See Flint (1993) pp. 277-78 for a detailed explanation, and Gibson (2011) pp. 115-134 about group structures in general in Xenakis music. this is the opposite of the phenomenon described earlier, since the rhythmic grouping remains steady while the pitches are commuted. A first example can be found in its simplest form in Psappha (section 325-377) where the composer exposes the six possible permutations obtained with three pitches and three consecutive sounds (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Psappha5Iannis Xenakis, Psappha, © 1976 Ed. Salabert. (section 325-377), systematic permutation of pitches in instruments of category B.

The same permutation process has been applied by Xenakis in Rebonds A, at the very beginning of the work where the composer exposes the basic “melodic” material of the piece that consists of seven drums, from two bass drums in the low range to two bongos in the high range. Beginning with the groups of three notes, then of four notes, Xenakis sets the pitches placed at the extremes of the range as anchors and changes the pitch of the third or fourth note of the group in ascending order, then descending order, before combining both ascending and descending figures (Figure 6).6De Cock (2015) presents an excerpt of the sketches where the composer traces lines between consecutive notes, thus creating small geometric figures that highlight the importance he gave to the shape of the melodic contour and to its progressive extension.

Figure 6: Rebonds A, mm. 1-6, progressive permutation of pitches in groups of three, then groups of four notes, in ascending order, descending order, and in both directions.

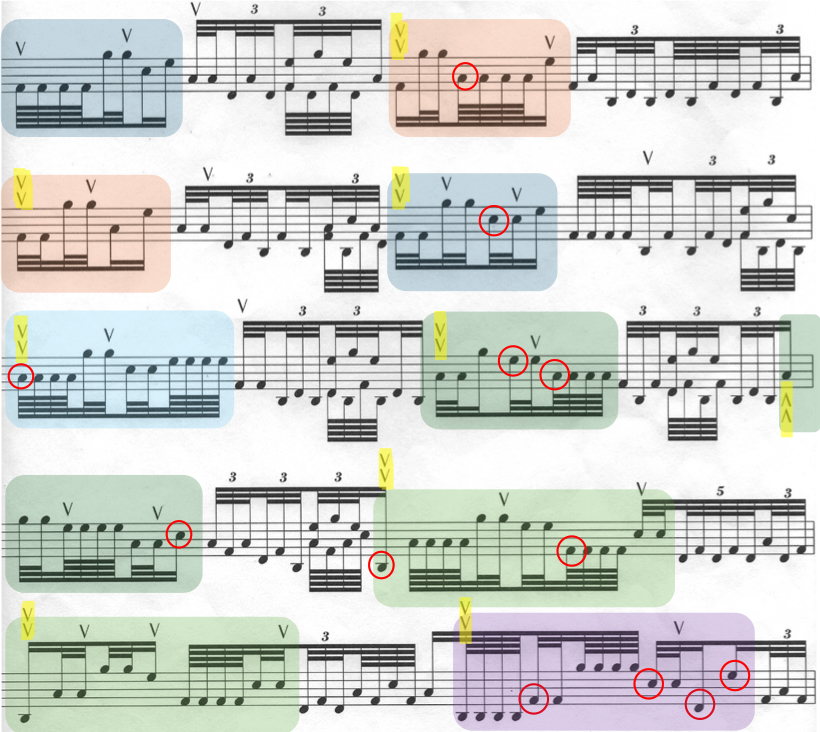

This basic melodic material will be varied throughout the movement and can be traced up almost to the end of the movement, that finishes as it began, using only the two drums at the extreme ranges of the register. In the section preceding the end of the work, which consists of a gradual densification of rhythm and polyrhythms, we can identify the same permutation process where a ‘melodic’ motif based on four notes at the outset develops to a motif of six notes, progressively permuting pitches. The segmentation of the following example (Figure 7) in a two-part pattern is based on Ben Duinker’s analysis (Duinker 2021) that juxtaposes a short melodic motif characterized by an overall ascending contour and starting with a double-accented note, with groups that present increased rhythmic density and polyrhythms. Pitches that are modified from one occurrence to the next are circled in red (Figure 7), while the colour code helps to identify motifs that present identical melodic contours.

Figure 7: Rebonds A, mm. 40-44, permutation of pitches and extension of the motif. Red circles signal pitch modifications from one occurrence to the next. Motifs with the same colour present identical melodic contours.

Once again, being able to identify such groupings and the processes that progressively transform them, is an invaluable tool for a more complete comprehension of the work, which will nurture the decision-making process underlying interpretative choices. It also facilitates the recognition of sub-groups large enough to be useful for phrasing purposes, but small enough to enhance the retention of the musical text.

Analyzing as a performer

I have already advocated the necessity for a performer to form their own understanding, through analysis, of the musical work that they interpret, and the benefits of this approach. Whether this process remains informal (mainly a mental guide) or becomes explicit as I will demonstrate in subsequent examples, it is always present to a certain degree. Why not then refer to existing analyses, realized for example by music theorists, when they are available?

Analyses realized by music theorists are of course of primary importance to performers, broadly ranging from the uncovering of compositional processes that underline the structure of a work (often referencing previous or successive works, sketches and other contextual information), to approaches that provide insights into perceptive and aesthetic aspects of the works.7Such approaches to Xenakis’s works can be found in Naud (1975), Uno & Hübscher (1995), Harley (2001) and Squibs (2001). However, I believe that performers’ analytical processes tend to be rooted in more pragmatic approaches, aiming to disambiguate interpretative choices. Such processes are often applied locally, i.e. on segments of a piece rather than on entire works, and implemented at various level of analysis, or at various scales. In other words, where music theorists generally aim for exhaustive and comprehensive work analysis, performers tend to apply a pragmatic approach that, more often than not, includes criteria based on their instrumental or vocal technical expertise. I will exemplify this point with Psappha.

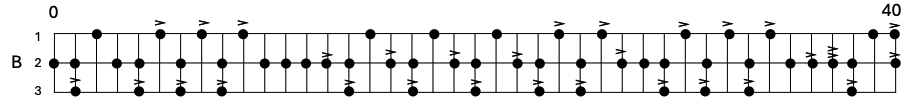

Music theorist Ellen Rennie Flint produced an impressive analytical work on Psappha (Flint 1993), in which she explains in detail the various principles used by the composer to create the fundamental elements of the work (sieves) and the many ways they are developed throughout the work (arborescences). At the beginning of the piece, where three instruments of the category B are performed, she identifies and analyzes the process for each instrument separately from the others, reproducing Xenakis’s compositional approach, and then describes this section as a “threefold metric scheme” (Flint 1993, p. 234). This description could be expressed in the performance if 1) the instruments were distributed across a stage amongst different performers, providing a spatialization of the sound in three distinct voices and/or 2) the instruments were of very different nature. However, as this is not the case, the perception of this sequence does not reflect the principles with which the score was elaborated. Media 1 provides a comparison of the opening section of Psappha (Figure 8) performed by three percussionists dispersed on stage, each playing one drum, versus a single musician performing the same sequence as written.

Figure 8: Psappha (section 0-40), reproduction of the opening section that features three instruments of category B.

Media 1: Psappha, Iannis Xenakis (1976); opening section of the work, (0-40) comparing a version where each drum is played by a different percussionist to a version played in the usual way. Watch Media 1.

Moreover, Flint omits the accents in her analysis to focus on the time distribution of the attacks based on the sieves, even though the score shows that accents are integral to this opening section. This is especially important in this work since the composer specifies, in an explanatory performance note at the end of the score, that accents may mean different things within the same sequence: increased intensity, sudden change of timbre, sudden change of weight, sudden addition of another sound to be played with the non-accentuated drum, combination of all previous possibilities. As a result, performers must proceed with their own segmentation of this section to bring forward the “rhythmic structures and architectures”, as recommended by Xenakis in his performance note (Xenakis 1976, p. 9).

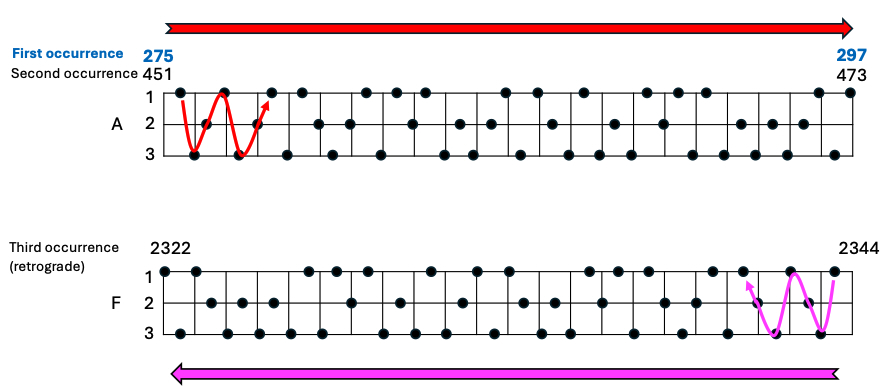

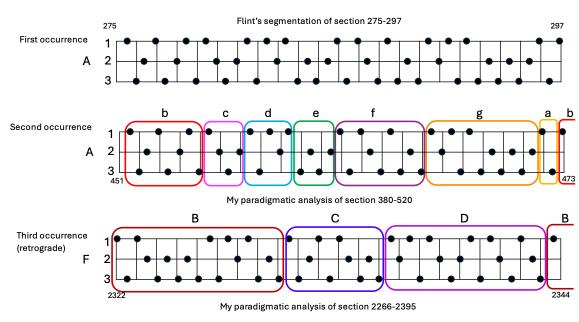

Flint also offers a very detailed explanation of the mechanisms underlying the construction of two long sequences of almost uninterrupted notes in the work, in sections 380-518 (instruments of category A) and 2277-end (instruments of category F), which are notoriously difficult to learn and perform accurately. In this case, her analysis, which reconstructs the entire structure of these sections based on groups of three pitches, is too granular to provide an anchor for the interpreter. However, extremely interesting for the performer is her identification of the pattern found in section 275-297—repeated in the middle of a long sequence in section 451-473 and replicated, but as an exact retrograde, also in the middle of a long sequence in section 2322-2344—since this pattern provides a tangible connection between these three sections of the work (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Identification by Flint of a pattern within a long sequence presented in full in three different parts in the work (sections 275-297 and 451-473 on instruments of category A, and 2322-2344 on instruments of category F), the last one being presented in retrograde. Only the melodic contour has been kept in this transcription.

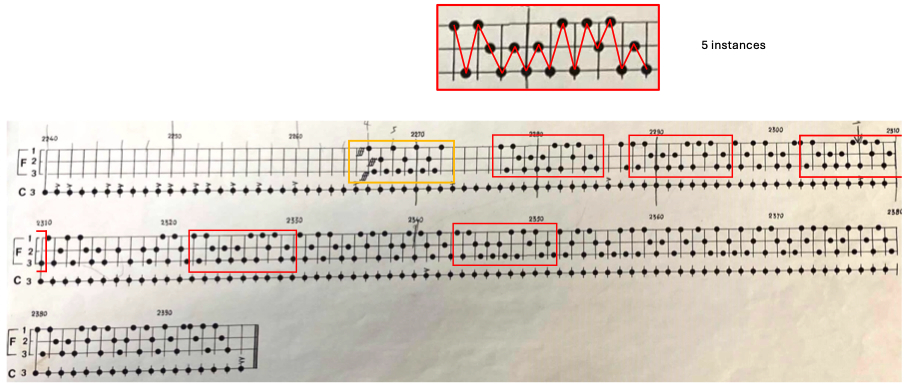

When I first had to learn Psappha, I was (as usual) in a bit of a rush, and as I was reading the score in the early stages of my practice, I had the intuition that I was recognizing patterns, without being able to easily identify them. This set me in motion to apply the paradigmatic approach: beginning with the last section of the score (2266-2395), which does not include any accents, and basing my analytical approach on my performance and analytical experience with Rebonds and Pleiades, as well as following Ruwet’s recommendations, I started looking for the longest possible sequence along the syntagmatic chain (the succession of musical events as they appear in the score) where melodic contour would be repeated. After isolating a sequence that imitated the initial pattern played on instruments A at the beginning of the work (in yellow in Figure 10), I proceeded to the next pattern and identified five identical instances of this second pattern (in red in Figure 10).

Figure 10: Psappha (section 2266-2395). Identification of the two first patterns presented in instruments of category F, highlighted in yellow and red.

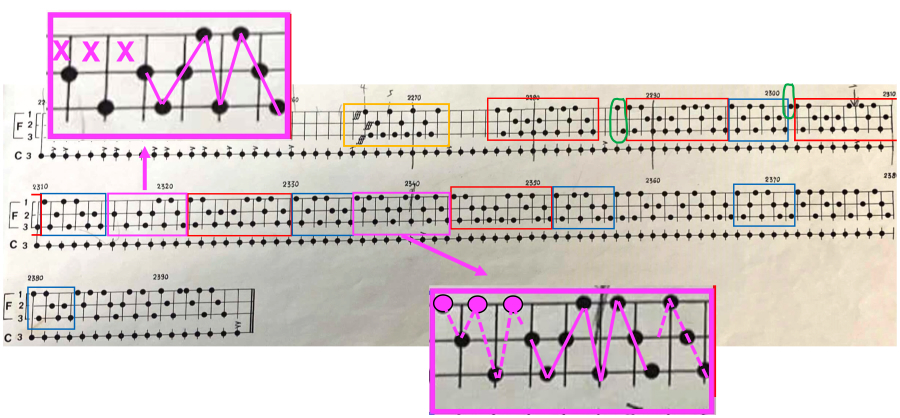

I continued to apply the same method throughout the score, although such a process is never totally straight forward, since Xenakis often introduces micro-variants of rhythm or pitch that tend to obfuscate the identification of patterns. For example, the fourth pattern that I identified is presented the first time with three rests instead of strokes, and is truncated, missing the final strokes of the pattern (Figure 11).

Figure 11: Psappha (section 2266-2395). Identification of the fourth pattern, the first instance of which presents small differences from the following iterations (X vs. circle).

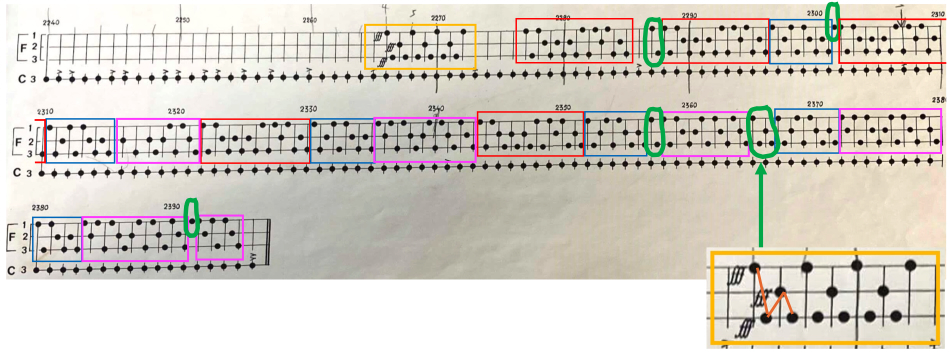

The identification of the larger patterns omitted certain notes (circled in green in Figure 11 and 12), and I had to determine their status: were they to be integrated as variants to adjacent patterns, or were they significant on their own? Considering the specific melodic contour of the longest pattern (four notes) of this series of omitted notes, I identified them as the incipit of the very first pattern of this final section and grouped them as belonging to the same paradigm as this pattern (Figure 12).

Figure 12: Psappha (section 2266-2395). The short series of notes omitted from the main patterns, circled in green, are identified as belonging to the first pattern of this section (framed in yellow).

The final segmentation of this section can then be summarized as four main patterns and their variants (Figure 13). C-3 means that this variant presents three fewer notes that the longest pattern of the paradigm, which is identified with the letter C.

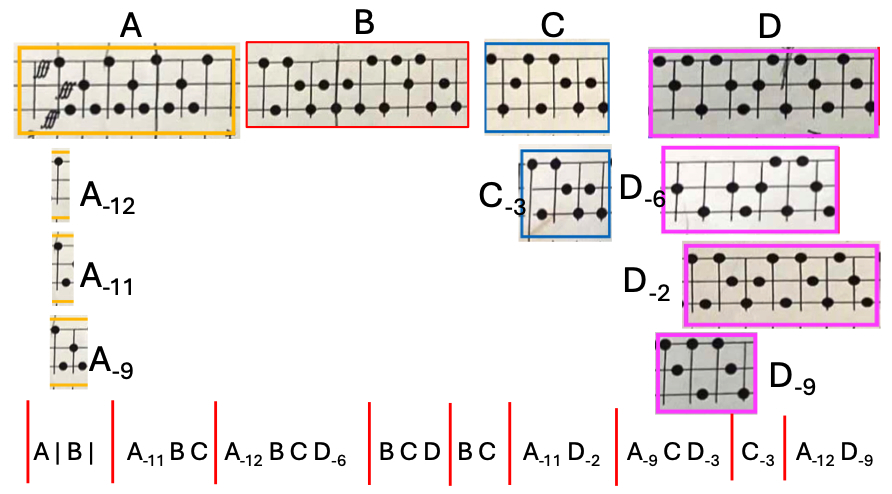

Figure 13: Psappha (section 2266-2395). Final segmentation identifying four main patterns (A to D) and their variants (A-11, etc.) where the index number indicates the number of notes that are absent from this variant, in comparison to the main pattern.

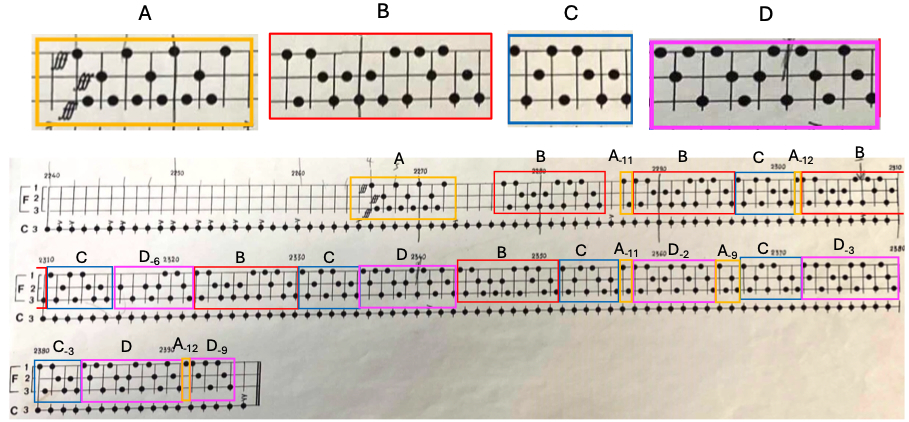

As a result, it is possible to put together a paradigmatic table of the four main patterns and their variants within the section, superimposed to showcase their similarities and discrepancies (Figure 14).

Figure 14: Psappha, paradigmatic table of the last section (2266-2395) representing the four main patterns and their variants for instruments of category F. The bottom line represents the succession in time of the patterns in this section.

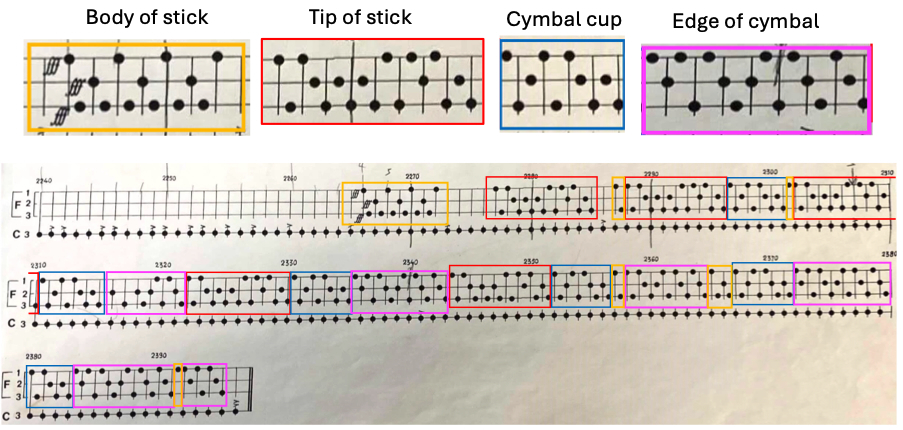

This type of analysis considerably reduces the number of elements to learn, creating relationships between them, and may also be used to underline the inner structure of this final section of the work by modifying the timbre depending on the pattern. Following Xenakis’s recommendation, as mentioned earlier, to highlight the rhythmic structures and architecture of the piece, I decided to use four different types of attack, creating as many timbral variations, to interpret this section. Playing on three cymbals, I chose to use the body of the stick on the main part of the cymbal for pattern A for a powerful and brassy sound, the tip of the stick for more distinct and lighter attacks for pattern B—also played on the main part of the cymbal—strokes on the cup (or bell) of the cymbal for a higher pitched sound for pattern C, and strokes produced with the sticks hitting the edge of the cymbal perpendicularly, for a sound with a noisier but less metallic attack for pattern D (Figure 15 and Media 2).

Media 2: Psappha, Iannis Xenakis (1976); final section of the work, (2255-2396) illustrating the use of timbral variations. Watch Media 2.

Figure 15: Psappha, final section (2266-2396). Example of the application of timbral changes to reflect the inner rhythmic architecture of this section, where each pattern is identified by a different way to strike the cymbals (instruments that I selected for the instruments of category F).

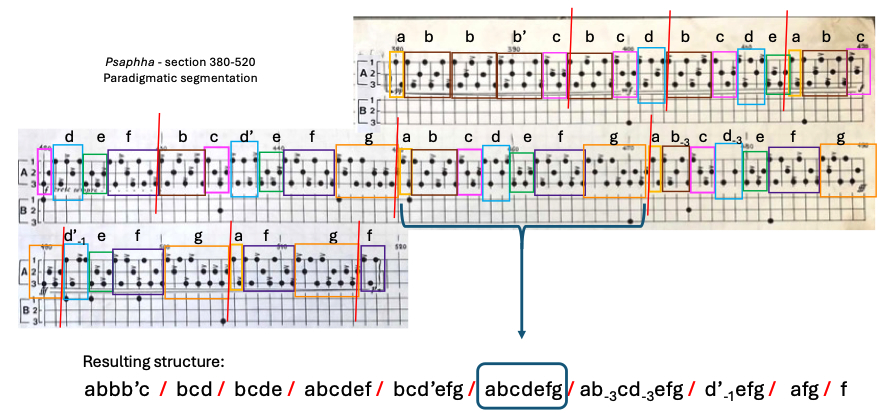

I employed the same method for section 380-518, which is quite similar, but played on the instruments of category A. Small letters8There is no relationship between segments identified with small and upper-case letters, i.e. between segments “A” in Figures 13 and 14 and segments “a” in Figures 16 and 18. (Figure 16) distinguish these patterns from the final section, and the composer’s progressive construction of the material—adding new patterns until he reaches the completion of this sequence [abcedfg], before deconstructing it—is even more evident here than in the final section, a process that Flint refers to as accretion and deletion (Flint 1993, p. 244).

Figure 16: Psappha, section 380-518. Segmentation and identification of seven short patterns that progressively accumulate until reaching the full sequence [abcdefg], and the deconstruction of the sequence, for the instruments of category A.

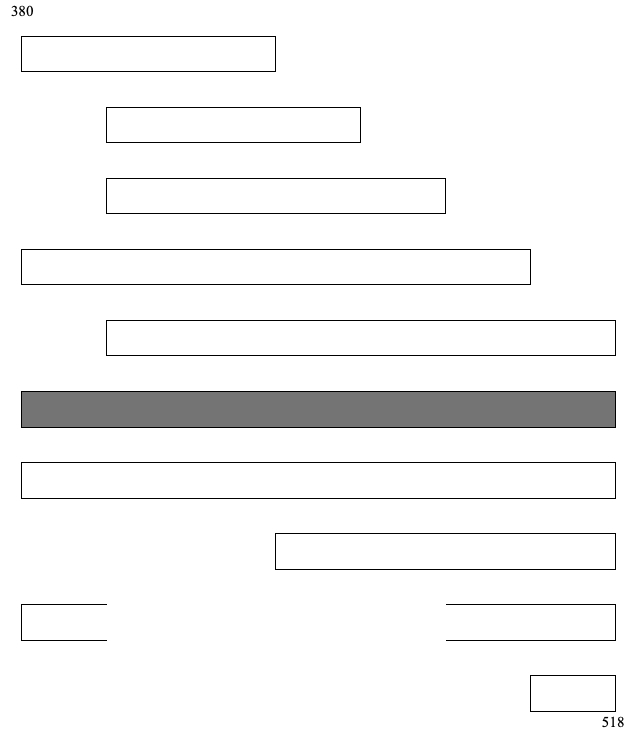

It should be noted that this segmentation is solely based on the melodic contour and does not take accentuation into account, which would lead to a different identification of the variants. Another strategy could be to select the longest segment [abcdefg] and consider it the main pattern, which would be preceded by five variants becoming progressively longer, and followed by four variants becoming progressively shorter, as described in Figure 17.

Figure 17: Psappha, section 380-518. Alternative paradigmatic representation of the segmentation of this section, based on the longest pattern (in grey) and considering the others to be variants of this pattern. The superimposition of consecutive patterns identifies sequences that are similar from one variant to the next.

The preceding examples (Fig. 16 and 17) offer two ways of looking at the same musical material with different focuses: the first example provides a more granular approach, allowing for a detailed comparison of the components that make up the larger structure, while the second example zooms out to focus on larger sequences. Both analyses are valid and might correspond to approaches that could be employed by different performers, each choosing the path that would facilitate their individual learning journey. However, these approaches may also represent various stages of discovery, learning, assimilation and interpretation for a single interpreter, thus reflecting the constant evolution over time of a performer’s relationship to a musical work—especially when the work is complex and requires a tremendous effort to learn and then recall it for every performance thereafter.

Another interesting point to note is that my paradigmatic analysis of sections 350-518 and 2266-2395 demonstrates that the main pattern, which is presented in full in the middle of each of these sections, is slightly shorter than what Flint identifies (Figure 18); I would argue that the last time unit in section 275-297 and the last two time units in section 2322-2344 (retrograde version) are in fact the repetition of the beginning of the pattern she identifies as being repeated from the first section (275-297). Figure 18 revisits Flint’s segmentation and identification of the same pattern and its retrograde (Figure 9), with my annotations reflecting my own segmentation, as presented in Figures 13 and 16.9It is interesting to note that the presentation of the material in its original version and retrograde lead to two different segmentations.

Figure 18: Psappha, comparison of the sequence identified by Flint in section 275-297 with the segmentation into patterns of the same sequence (and its retrograde) that I realized for sections 350-518 and 2266-2395.

These small discrepancies bring to light the difficulties that may arise when making final decisions on the criteria that we use to segment the musical material. In this case, one could decide to take the sequence identified by Flint (275-297) as the main reference, but for the two following sections, it would complicate the identification of the units that are used in the construction and deconstruction of the sequence, which would consequently make the interpreter’s task more difficult than necessary. In the same manner that Flint identified the sequence in section 275-297, I also tend to begin segmenting from the onset of any new sequence, which is marked by a preceding silence or change of instrumentation. This means that my interpretation of section 380-520 favours the sequence [abcdefg] as the main sequence (Fig. 16)—repeated once with slight variants (six notes are left out in the repetition)—which also corresponds to the end of the long crescendo, immediately followed by a rapid decrescendo coinciding with the deconstruction phase.

Paradigm and polyphony

Paradigmatic analysis is efficient for the segmentation of monodic music; however, as mentioned by Ruwet, “it would be very difficult to apply the same procedure to the presentation of polyphonic structures” (Ruwet 1987, p. 20). Abromont (2021) nuances this statement by confirming that the study of “polyphonic music presents major difficulties and is less frequently addressed. When it is, it is often a question of isolating monodic strata, which are then analysed in the same way as melodies.”10“Les musiques polyphoniques présentent d’importantes difficultés et sont moins fréquemment abordées, et, quand elles le sont, il s’agit souvent d’isoler des strates monodiques qui seront ensuite analysées à la façon de mélodies.” Abromont (2021), my translation.

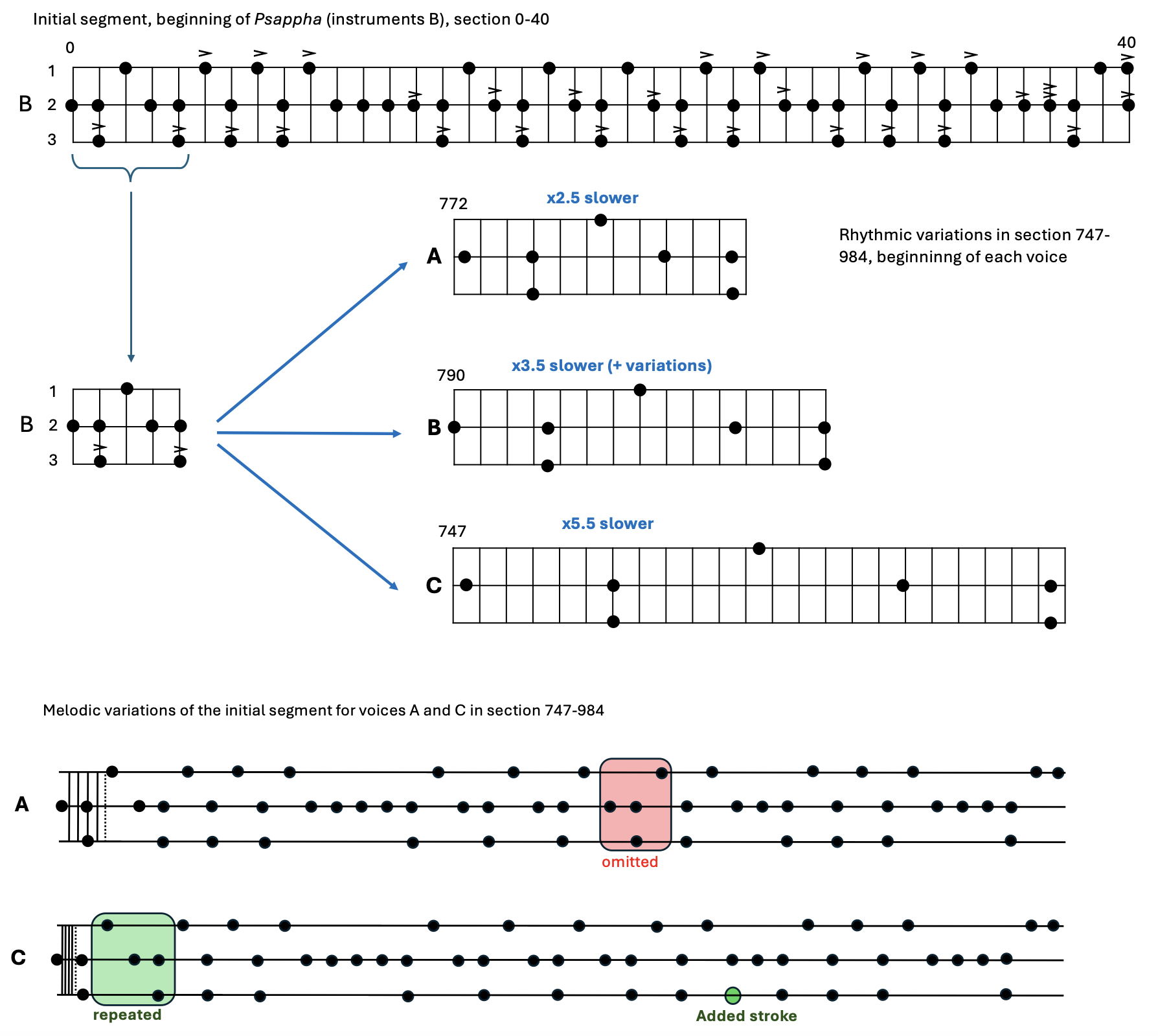

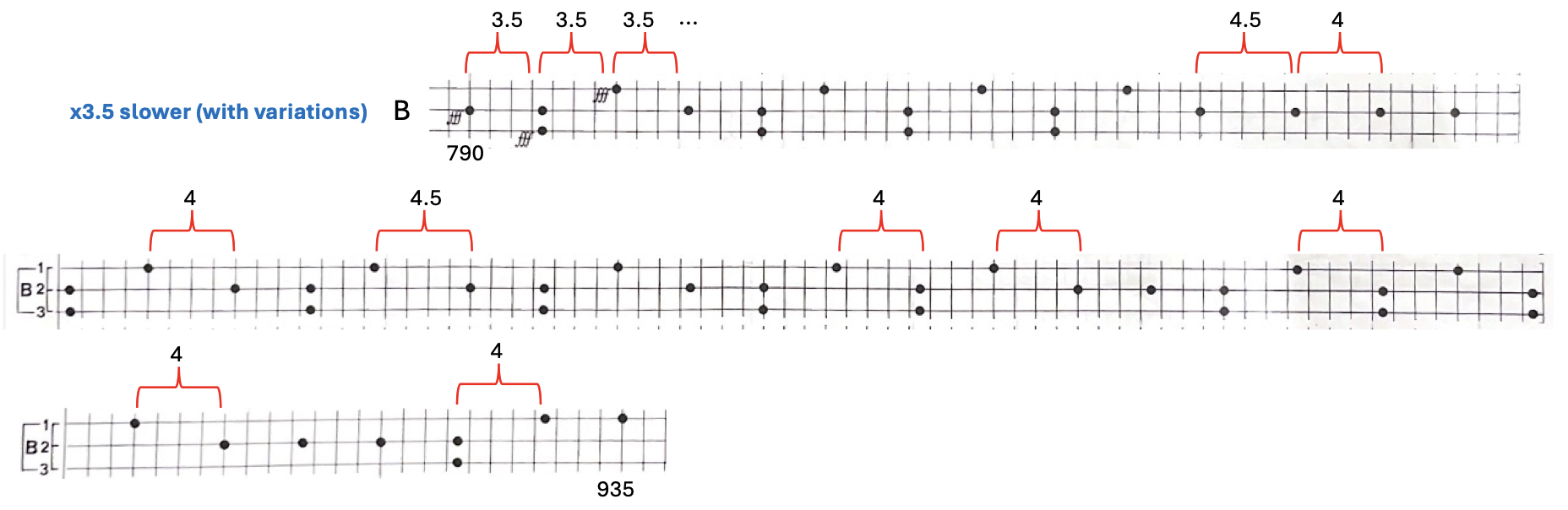

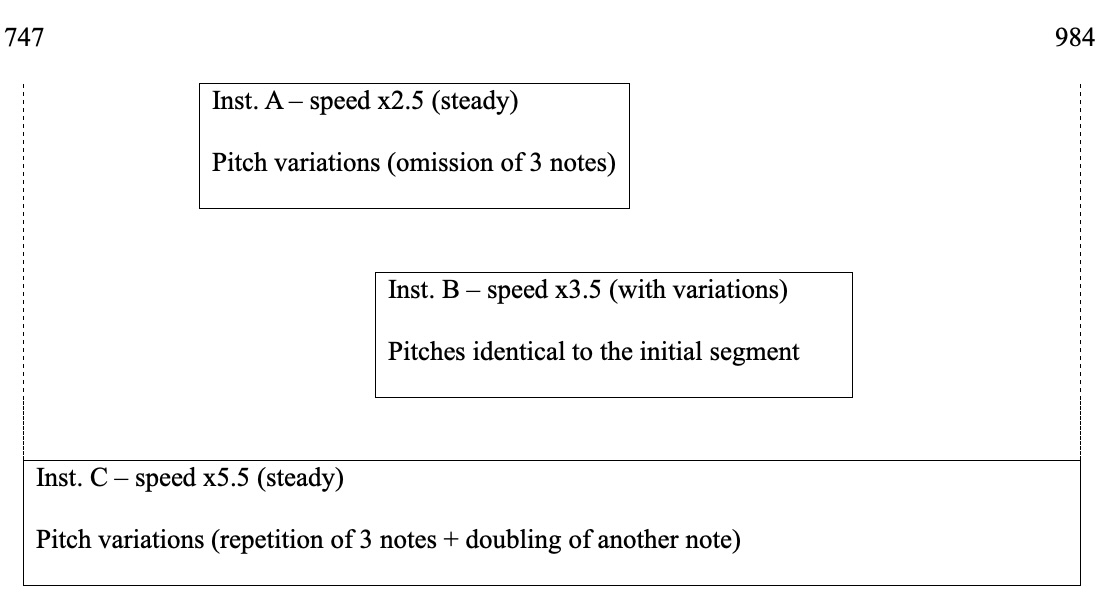

It remains of interest to use this technique to analyze the transformation of some of the musical material through a polyphonic work, especially in sections that use contrapuntal tools such as canon, fugue, etc. In Psappha, this applies to section 747-984, which presents a canon spread over three categories of instruments: A, B and C. Here, Xenakis uses the musical material presented in the introduction of the work on instruments B but at slower timing rates: instruments A are 2.5 times slower than the original presentation, instruments B are 3.5 times slower, and instruments C are 5.5 times slower. However, a comparison term-to-term of each of these voices with the original content (Figure 19) reveals they all present slight differences: pitch variations and the omission of three notes for instruments A; speed variations for instruments B; and pitch variations with the repetition of three notes and the doubling of another one for instruments C.

Figure 19: Psappha, section 747-984. Comparison of the opening of the work (section 0-40) with layers of categories A, B, and C, highlighting the differences in speed and pitch.

Figure 20: Psappha – Variations of durations for instruments of category B in the canon section (790-935) compared to the initial segment (0-40). Initial section reproduced from 3.5 to 4.5 times slower.

The overall structure of this canon section is summarized in Figure 21.

Figure 21: Psappha: Overview of the three layers in the canon of section 747-984 and their relationship to the initial sequence of the work (section 0-40).

The analysis of the canon that constitutes this section may help the performer in various ways: highlighting the slight differences that occur from one voice to the next in terms of melodic contour, facilitating the memorization of the passage, and helping the performer focus on certain aspects of the recuring pattern that can be brought to the fore to facilitate the audience’s perception of this rhythmic canon. For instance, one can try to emphasize the beginning and end of each voice, both sonically and visually, by using, for example, larger and more connected movements on each category of instruments.[11]

Coda

Using Psappha and Rebonds as examples, I have aimed to provide examples of how the use of paradigmatic analysis can help performers acquire a deeper understanding of a musical score’s underlying structures. Implementing these tools has proved useful to me, to accelerate the learning process and to create more advantageous conditions for longer term retention—or quicker re-learning—of such works. One of the salient features of paradigmatic analysis is that it can be applied to a musical work at various stages, depending on the musical elements that are of interest to the analyst, and on the marks that are selected to produce the segmentation. Paradigmatic analysis aligns very well with the needs of performers, who often do not need to realize a full and systematic analysis of a complete work, but rather one of certain aspects or sections. By making tangible an analytical process that always takes place during the learning phase of a musical work (musicians always segment and group music into patterns, following obvious markings such as phrasing indications, dynamics, metric grouping, etc.), paradigmatic analysis provides an excellent tool to practice self-criticism since it helps to verify that a performer’s interpretative approach remains coherent. The main danger with the formalization of such an analysis may be to provide too rigid a guide for the long-term: analysis can always be questioned and revised, to shed new light on even the most familiar works.

Thanks

I would like to express my sincere thanks to Kristie Ibrahim for her assistance revising the English version of this text.

Bibliography

Abromont, Claude (2021), “Variations sur l’analyse paradigmatique”, Actes du colloque Autour des écrits de Jean-Jacques Nattiez (Conservatoire de Paris, 12 November 2015), Les Éditions du Conservatoire, https://www.conservatoiredeparis.fr/fr/variations-sur-lanalyse-paradigmatique, accessed 19 May 2025.

Alvarez-Pereyre, Frank and Simha Arom (1993), “Ethnomusicology and the Emic/Etic Issue », The World of Music, “Emics and Etics in Ethnomusicology”, vol. 35, no 1, pp. 7–33.

Arom, Simha (1981), “New Perspectives for the Description of Orally Transmitted Music », The World of Music, vol. 23, no 2, pp. 40–62.

Arom, Simha (1989), “Time Structure in the Music of Central Africa. Periodicity, Meter, Rhythm and Polyrhythmics”, Leonardo, vol. 22, no 1, pp. 91–99.

Arom, Simha (1991), African Polyphony and Polyrhythm. Musical Structure and Methodology, translated from French by Martin Thom, Barbara Tuckett and Raymond Boyd, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

De Cock, Tom (2015), Living Scores Learn, Iannis Xenakis. Rebonds,

https://www.living-scores.com/learn/platform/iannisxenakis/compositions/rebonds/, accessed 20 June 2025.

Duinker, Ben (2021), “Rebonds. Structural Affordances, Negotiation, and Creation”, Music Theory Online, vol. 27, no 4, https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.21.27.4/mto.21.27.4.duinker.html, DOI: 10.30535/mto.27.4.5.

Flint, Ellen Rennie (1993), “Metabolae, Arborescences and Reconstruction of Time in Iannis Xenakis’s ‘Psappha’”, Contemporary Music Review, vol. 7, p. 22–48.

Gibson, Benoît (2011), The Instrumental Music of Iannis Xenakis. Theory, Practice, Self-Borrowing, New York, Pendragon Press.

Gualda, Sylvio (2010), “On Psappha and Persephassa”, in Sharon Kanach (ed.), Performing Xenakis, New-York, Pendragon Press, pp. 159–166.

Harley, James (2001), “Formal Analysis of the Music of Iannis Xenakis by Means of Sonic Events. Recent Orchestral Works”, in Makis Solomos (ed.), Présences de Iannis Xenakis, Paris, CDMC, pp. 37–52.

Marandola, Fabrice (2012), “Of Paradigms and Drums. Analyzing and Performing ‘Peaux’ from Pleiades”, in Sharon Kanach (ed.), Xenakis Matters. Contexts, Processes, Applications, Pendragon Press, pp. 185–204.

Nattiez, Jean-Jacques (2003), “Modèles linguistiques et analyse des structures musicales”, Canadian University Music Review / Revue de musique des universités canadiennes, vol. 23, no 1-2, pp. 10–61, https://doi.org/10.7202/1014517ar

Naud, Gilles (1975), “Aperçus d’une analyse sémiologique de Nomos Alpha”, Musique en Jeu, vol. 17, pp. 63–72.

Rouget, Gilbert (1961), “Un chromatisme africain”, L’Homme, tome 1, no 3, pp. 32–36.

Ruwet, Nicolas (1966), “Méthodes d’analyse en musicologie”, Revue belge de Musicologie / Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Muziekwetenschap, vol. 20, no 1/4, pp. 65–90.

Ruwet, Nicolas (1987), “Methods of Analysis in Musicology”, translated from French by Mark Everist, Music Analysis, vol. 6, no 1/2 pp. 11–36.

Squibbs, Ronald (2001), “A Methodological Problem and a Provisional Solution. An Analysis of Structure and Form in Xenakis’s Evryali”, in Makis Solomos (éd.), Présences de Iannis Xenakis, Paris, CDMC, 2001, pp. 153–158.

Uno, Yayoi and Roland Hübscher (1995), “Temporal Gestalt Segmentation: Polyphonic Extensions and Applications to Works by Boulez, Cage, Xenakis, Ligeti, and Babbitt”, Computers in Music Research 5, pp. 1-37.

Xenakis, Iannis (1976), Psappha, Éditions Salabert, EAS 17346.

Xenakis, Iannis (1991), Rebonds, Éditions Salabert, EAS 18707.

| RMO_vol.12.2_Marandola |

Attention : le logiciel Aperçu (preview) ne permet pas la lecture des fichiers sonores intégrés dans les fichiers pdf.

Citation

- Référence papier (pdf)

Fabrice Marandola, « Paradigmatic Analysis and the Performance of Xenakis’s Solo Percussion Music », Revue musicale OICRM, vol. 12, no 2, 2025, p. 129-150.

- Référence électronique

Fabrice Marandola, « Paradigmatic Analysis and the Performance of Xenakis’s Solo Percussion Music », Revue musicale OICRM, vol. 12, no 2, 2025, mis en ligne le 18 décembre 2025, https://revuemusicaleoicrm.org/rmo-vol12-n2/paradigmatic-analysis-performance-Xenakis-percussion/, consulté le…

Auteur

Fabrice Marandola, Université McGill

Fabrice Marandola est depuis 2005 Professeur agrégé de percussion et musique contemporaine à l’École de Musique Schulich de l’Université McGill. Très actif dans le domaine de la musique de création, il commande et interprète de nouvelles œuvres en solo ou en formation de chambre, notamment avec l’ensemble à percussion SIXTRUM dont il est l’un des fondateurs.

Titulaire d’un Premier Prix en percussion (CDNSM de Paris) et d’un PhD en ethnomusicologie (Paris IV-Sorbonne), il a été Directeur du Centre Interdisciplinaire de Recherche en Musique, Médias et Technologie de 2020 à 2024, et a réalisé de nombreuses recherches de terrain au Cameroun.

Notes

| ↵1 | The publications dates for Psappha and Rebonds by Éditions Salabert are respectively 1976 and 1987. |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | For more information on Gualda and Xenakis collaboration, see Gualda (2010). |

| ↵3 | Iannis Xenakis, Rebonds A & B, © 1987 Ed. Salabert. |

| ↵4 | See Flint (1993) pp. 277-78 for a detailed explanation, and Gibson (2011) pp. 115-134 about group structures in general in Xenakis music. |

| ↵5 | Iannis Xenakis, Psappha, © 1976 Ed. Salabert. |

| ↵6 | De Cock (2015) presents an excerpt of the sketches where the composer traces lines between consecutive notes, thus creating small geometric figures that highlight the importance he gave to the shape of the melodic contour and to its progressive extension. |

| ↵7 | Such approaches to Xenakis’s works can be found in Naud (1975), Uno & Hübscher (1995), Harley (2001) and Squibs (2001). |

| ↵8 | There is no relationship between segments identified with small and upper-case letters, i.e. between segments “A” in Figures 13 and 14 and segments “a” in Figures 16 and 18. |

| ↵9 | It is interesting to note that the presentation of the material in its original version and retrograde lead to two different segmentations. |

| ↵10 | “Les musiques polyphoniques présentent d’importantes difficultés et sont moins fréquemment abordées, et, quand elles le sont, il s’agit souvent d’isoler des strates monodiques qui seront ensuite analysées à la façon de mélodies.” Abromont (2021), my translation. |