Finding a Fingerprint. Microtiming and Tempo Variability in Five Renowned Rock Drummers

David S. Carter and Ralf von Appen

| PDF | CITATION | AUTEURS |

Abstract

In this article, we analyze microtiming and tempo variability in the music of five renowned rock drummers: Ringo Starr, Mitch Mitchell, Stewart Copeland, Phil Rudd, and Meg White. Using the applications Moises and Sonic Visualiser, we isolated the drum stems of 79 studio and live recordings and determined exact quarter-note positions in backbeat patterns. We used metrics such as the normalized absolute deviation beat sum, average beat coefficient of variation, and tempo coefficient of variation in order to capture these drummers’ distinctive “fingerprints.” We found that Starr showed a propensity for delayed backbeats and slowing down, Copeland a tendency for early backbeats, Rudd steadiness without a click track, and Mitchell and White a propensity towards wide variability in timing and tempo. The results of this exploratory study suggest that drumming characteristics are shaped not only by personal style but also by broader historical trends.

Keywords: drumming; microtiming; rhythm; rock music; tempo variability.

Résumé

Dans cet article, nous analysons le microtiming et la variabilité du tempo dans la musique de cinq batteurs emblématiques du rock : Ringo Starr, Mitch Mitchell, Stewart Copeland, Phil Rudd et Meg White. À l’aide des applications Moises et Sonic Visualiser, nous avons isolé les pistes de batterie de 79 enregistrements studio et live, puis déterminé les positions exactes des temps à la noire dans des patrons de backbeat. Nous avons mobilisé des mesures telles que la somme normalisée des écarts absolus des pulsations, le coefficient de variation moyen des pulsations et le coefficient de variation du tempo afin de mettre en évidence les « empreintes » distinctives de ces batteurs. Nos résultats montrent que Starr présente une tendance à des backbeats retardés et à un ralentissement progressif, Copeland une propension à des backbeats anticipés, Rudd une remarquable constance en l’absence de click track, et Mitchell ainsi que White une forte variabilité dans le timing et le tempo. Les conclusions de cette étude exploratoire suggèrent que les caractéristiques de jeu des batteurs sont façonnées non seulement par leur style personnel, mais également par des tendances historiques plus larges.

Mots clés : batterie ; microtiming ; musique rock ; rythme ; variabilité du tempo.

Introduction

While most studies of microtiming and groove in popular music have relied on laboratory experiments, a growing number have instead analyzed commercially released recordings of renowned musicians (see Frane 2017; Peterson 2018; Wahlström 2022; Ainsworth 2024; Cheston et al. 2024b). Most of these analyses, however, have concentrated only on very brief passages where drummers were playing solo, given that individual instrumental stems are rarely available. Additionally, songs recorded without a click track have a constantly varying tempo, making measurement of microtiming deviations a complex and potentially speculative task.

Recent advances in machine learning have enabled the high-quality isolation of individual instruments, opening up new avenues for microtiming analysis. Cheston et al. (2024b) took advantage of these innovations in order to study the rhythmic characteristics of famous jazz pianists.1This study had moderate success with distinguishing pianists solely on the basis of their rhythmic characteristics, with the pianists’ mean lag behind the drummer’s beat being the most reliable means of distinction (2024b, p. 11). In our study, we use related source separation technology to investigate timing and tempo variability in the performances of five renowned rock drummers: Ringo Starr of the Beatles, Mitch Mitchell of the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Phil Rudd of AC/DC, Stewart Copeland of the Police, and Meg White of the White Stripes. Our approach allows us to statistically analyze a larger group of complete songs, providing quantitative insights into these drummers’ playing. Our study finds that each drummer exhibits measurable characteristics that in most cases, though not always, correlate with their existing reputations. While our focus on quarter-note timing encompasses just one aspect of their drumming, the results for the five drummers are distinctive enough to contribute to the sense of a “fingerprint” for each. Our insights not only increase understanding of these performers but also can inform future corpus analyses of tempo and timing.

Below, we first discuss our methodology. We then provide details on our findings regarding each drummer, proceeding in order of year of birth, and conclude with some thoughts on how the five relate to one another.

Methodology

For our study, we chose five drummers who we expected to feature distinct tempo and timing characteristics. These five represent chronological diversity within the rock era, with birth years between 1940 and 1974, and contrast in styles. Starr and Rudd have reputations for understated steadiness, Mitchell played psychedelic rock and was jazz-influenced, Copeland comes from a jazz background but combined rock and reggae, and White is known for a raw and ferocious simplicity. We analyzed between 15 and 17 recordings for each of the five drummers, 79 in total. Each selected recording had significant portions with a backbeat pattern or variant and a clearly audible kick and snare. The songs selected included some of the best-known tracks on which these drummers played as well as a selection of live recordings (see Discography below for details).2The BBC “live” recordings by the Beatles and the Jimi Hendrix Experience included in the study (three from each artist) were, despite the labeling of the Beatles release, prerecorded in a radio station studio without a live audience. All the live recordings except for one (“Every Breath You Take”) are part of a studio-live pairing of the same song.

We analyzed these recordings for both microtiming and tempo variability. With respect to microtiming, we built on the method initially presented in Carter and von Appen 2025a, an analysis of the drumming of Charlie Watts of the Rolling Stones. Our first task was to identify relevant drum attacks. We used the Moises Pro application to isolate the drums from the other instruments and separate the snare and kick into separate channels. We then employed the BBC Rhythm: Onsets plugin in the application Sonic Visualiser to automatically mark attacks.3See https://www.sonicvisualiser.org/ and https://www.vamp-plugins.org/download.html. Within the plugin, we used a Hann window shape, an FFT window size of 128 samples, and a window increment of 32. We started with a Threshold setting of three and then increased or decreased it to automatically mark the quarter notes. In cases where the algorithm did not detect an attack that actually occurred, we lowered the Threshold in a second layer and copied the resulting markers into the first layer. Baume (2013) discusses how the plugin works. Cheston et al. 2024a instead used a neural-network-based tool, CNNOnsetDetector within the Python library madmom, for detecting piano note onsets … Continue reading Using this plugin resulted in attack markers that were typically between the visual onset and the high point of energy of the attack, consistent with scholarly findings that the perceptual attack time typically falls in this area (Danielsen et al. 2019, p. 403). We exported the timing of those attack markers as a CSV (comma-separated values) file into Excel. In order to use the same template for every recording without having to make major adaptations, we only analyzed the quarter note attacks in songs with a standard backbeat pattern or variant.4The backbeat pattern, in which the bass drum plays on the first and third beats and the snare drum on the second and fourth beats of a 4/4 measure, is by far the most widespread accompaniment pattern across many styles of popular music. Allan Moore has called it the “standard rock beat” (1993, p. 38; see also Baur 2012; Brennan 2020, pp. 179–190). Playing eighth notes on hi-hats is a crucial component of rock drumming, but current technology often does not successfully separate out hi-hats, particularly in recordings released prior to 1980. In drum fills, we only measured the attacks that fell on quarter notes. If a quarter note did not have an attack, this resulted in a gap in the table. Each of these drummers would often play another pattern—Mitch Mitchell and Stewart Copeland in particular frequently played patterns contrasting with the standard backbeat—but we focused our analysis on quarter notes for simplicity, feasibility, and because the backbeat pattern constitutes a lingua franca shared among the five studied drummers and rock drummers more generally (Baur 2021, pp. 49–50). We excluded from our analysis passages without drums or where the drum pattern was not a backbeat variant.

Once we had identified quarter note onsets in the selected recordings, we sought to determine whether these attacks would be heard as “early” or “late” in relation to the beat. In a musical context in which a click track or sequence is not being used, tempo is always in flux, even with the steadiest drummers. Gradual tempo “drift” can result in subtle acceleration or slowing (Condit-Schultz and Clark 2024, p. 5; Carter and von Appen 2025b, p. 61). We measured microtiming deviations using both the previous bar’s tempo and the current bar’s tempo as reference points, as both approaches can potentially reflect how listeners hear.5References to “the listener” in this essay refer to an imagined average listener—not necessarily a music scholar or a trained listener. Individual listeners’ experiences can differ in important ways. But the difference between the perceptions of trained and untrained listeners in many cases is not large (London 2012, pp. 172–173), and the conjectured experience of an average listener can provide an important reference point for musical analysis. The tempo of the music the listener has already heard creates an isochronous expectation for future attacks, with the listener entraining to the beat (Brower 1993, pp. 26–27),6Researchers have differing views regarding how much time a listener considers when perceiving tempo (Bailes et al. 2013, p. 1). Frane (2017, p. 296), Freeman and Lacey (2002, p. 549), and Troes (2017, p. 35) use the current bar as the basis for measuring microtiming deviations. This approach, when applied to beats 2, 3, or 4, counter-intuitively compares attacks to attacks the listener has not yet heard. Butterfield (2006, pp. 50–51) and Frane (2017, p. 296) use the previous bar and previous beat, respectively, as secondary measurements for ascertaining the extent of deviations from the beat. and the placements of the actual attacks can be compared with that expectation. This expectation, with regard to a single, specific attack, is almost never a conscious expectation—it is rather ensconced within the subliminal perception of rhythm and relies on precognitive echoic memory (Brower 1993, pp. 21, 26).7This assumes that listeners have an expectation of isochrony (or at least near-isochrony) on some level, allowing them to entrain to a stream of pulses (Brower 1993, pp. 26–27). A listener who has heard a repeating pattern of microtiming deviation may develop an expectation that that pattern will continue, but even if that expectation is fulfilled it is on some level still a deviation from an isochronous expectation.

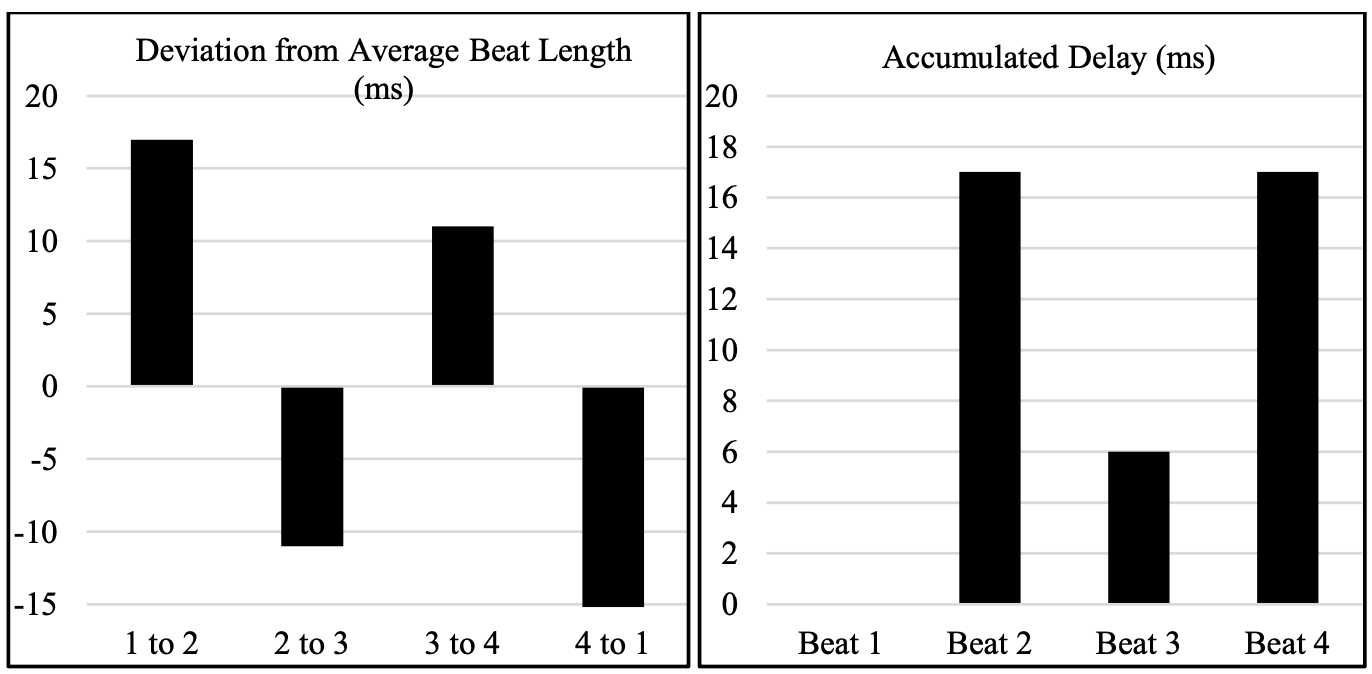

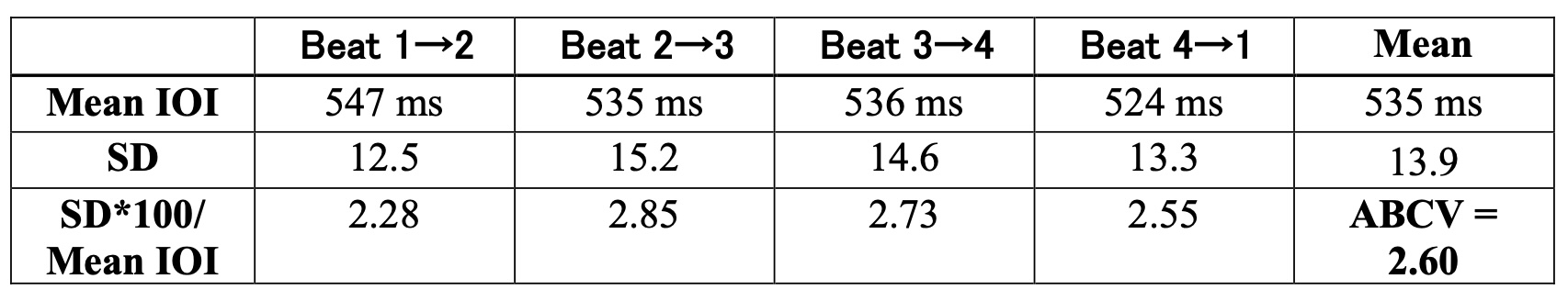

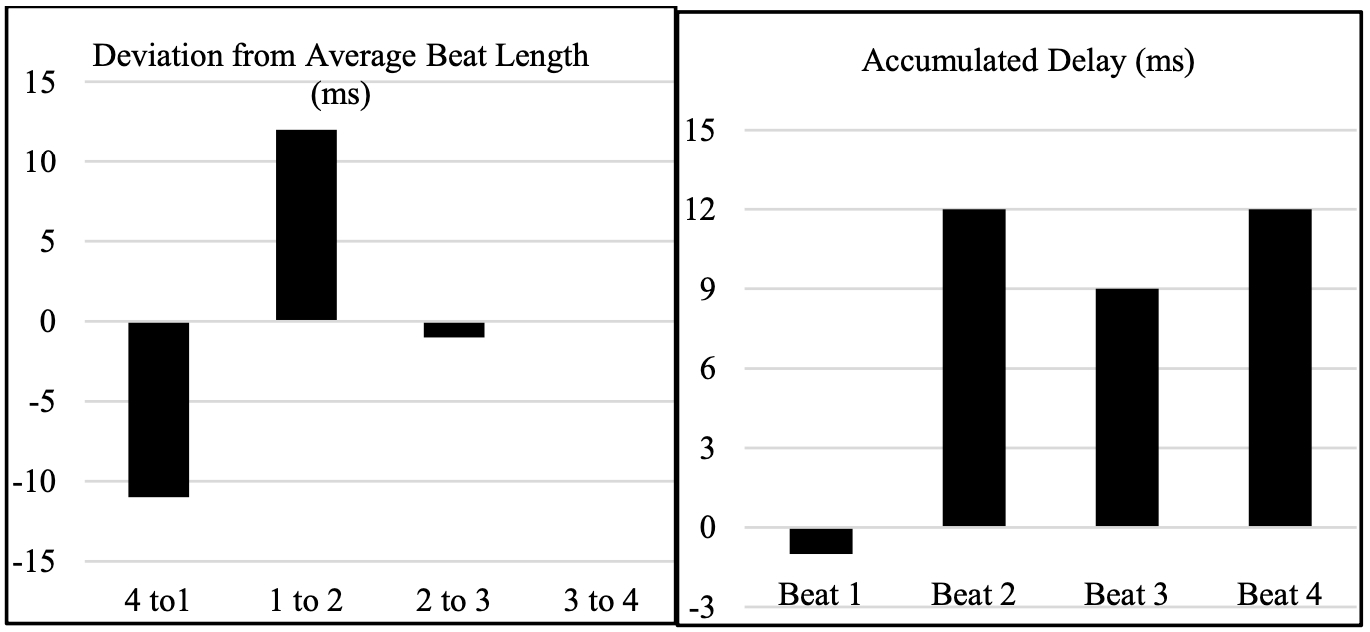

With the average beat length in the previous or current bar as a reference, we determined whether each interonset interval (time between consecutive attacks, or IOI) in a given bar was larger or smaller than that average. Just measuring the IOIs between consecutive quarter-note attacks, however, does not fully reflect how we hear. To some extent, listeners hear in relation to downbeats (Butterfield 2007, pp. 8–9; Brower 1993, pp. 26–27). If, as in Figure 1 and Media 1, the IOI between beats 1 and 2 is above average (+17 ms) and the IOI from 2 to 3 is below average with a smaller absolute deviation (-11 ms), a listener may not hear beat 3 as 11 ms early. The listener may hear the beat 3 attack as slightly delayed (+6 ms) in relation to the placement of the downbeat of the bar. Therefore, we also used an accumulated measurement in order to assess attack placement in relation to downbeats.

Using either the previous or current bar’s tempo and calculating values either beat-to-beat or accumulated across the bar gives four possible combinations: previous bar/beat-to-beat, previous bar/accumulated,8Using the previous/accumulated method, the microtiming deviation of downbeats was measured by comparing the length of the just-completed bar with that of the bar before that. This is consistent with our approach to the other three beats in the bar; with a downbeat, the “accumulated” time is necessarily an entire bar. current bar/beat-to-beat, and current bar/accumulated. Figure 2 shows a comparison of the differences in values resulting from using these four approaches, analyzing the same bar from the Beatles’ “With a Little Help from My Friends”9Recordings referenced in this article are studio recordings unless specifically labeled as live versions. used in Figure 1. The question of whether a given quarter-note attack is heard as “early” or “late” ultimately can vary from listener to listener. It is influenced not only by the timing of the kick and snare but also by the rhythms and timbres of other instruments in the texture. But for the sake of simplicity, we focus in this article on the previous/accumulated variant, as it perhaps best reflects how listeners perceive in real time.10While measurements of microtiming deviations calculated with reference to the previous bar perhaps better reflect the listener’s experience in real time, they are more sensitive to tempo fluctuations than measurements made using the current bar as the tempo reference. This is simply because a longer time period (including both the previous and current bars) is encompassed within the comparison. Additionally, our choice of the previous/accumulated method does not mean that the other three approaches lack validity in all instances or for all listeners. For instance, listeners will hear beat 3 and beat 4 attacks in part in relation to downbeats, but they also (even simultaneously) can hear … Continue reading

Figure 1: Different methods of calculating microtiming deviations for the Beatles’ “With a Little Help from My Friends,” fourth bar of first refrain. Both measurements assess deviation with reference to the mean IOI in the current bar.

Media 1: Four bars of isolated kick (above, panned left) and snare drum (below, panned right) of the Beatles’ “With a Little Help from My Friends” (1st refrain, 0:26–0:34). The fourth bar of the excerpt is the one represented in Figure 1. Red lines mark the quarter-note onsets of the kick drum and green lines mark the snare drum. Onset detection markers are heard as clicks. Listen to Media 1.

Figure 2: Different methods of calculating microtiming deviations for the Beatles’ “With a Little Help from My Friends,” fourth bar of first refrain (0:32–0:35).

In addition to determining whether an attack is early or late, it is essential to consider the extent to which such a deviation from expectation is perceptible by listeners. Research has shown that humans can recognize deviations from isochronous IOI patterns of 2.5% of the mean IOI or greater at tempos up to 250 BPM (Friberg and Sundberg 1995, p. 2528; Madison and Merker 2002, p. 204). Madison and Merker in a subsequent study, however, showed that listeners can subliminally respond to even smaller deviations, even if they may not be able to consciously recognize them (2004, p. 71). We have used the 2.5% of IOI standard as a heuristic for measuring whether a deviation is “substantial” or not. For each individual song example, we calculated the percentage of attacks on beats 2 and 4 that were at least 2.5% early, at least 2.5% late, or “on time” (-2.5% < n < 2.5%). We also calculated the average percentage deviation of beats 2 and 4 throughout the entire song or excerpt (“% Mean IOI”). Measuring the percentage of attacks that are at least 2.5% late shows the consistency of the delay and is the primary measurement that we will use when discussing individual drummers. We selectively supplement this measurement with calculations of the average delay as a percentage of mean IOI, a metric that is more sensitive to large individual deviations.

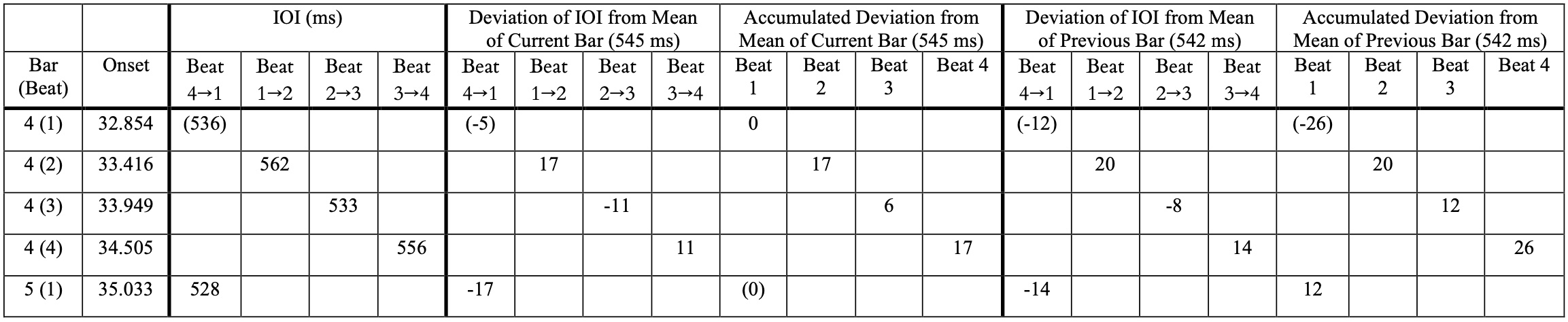

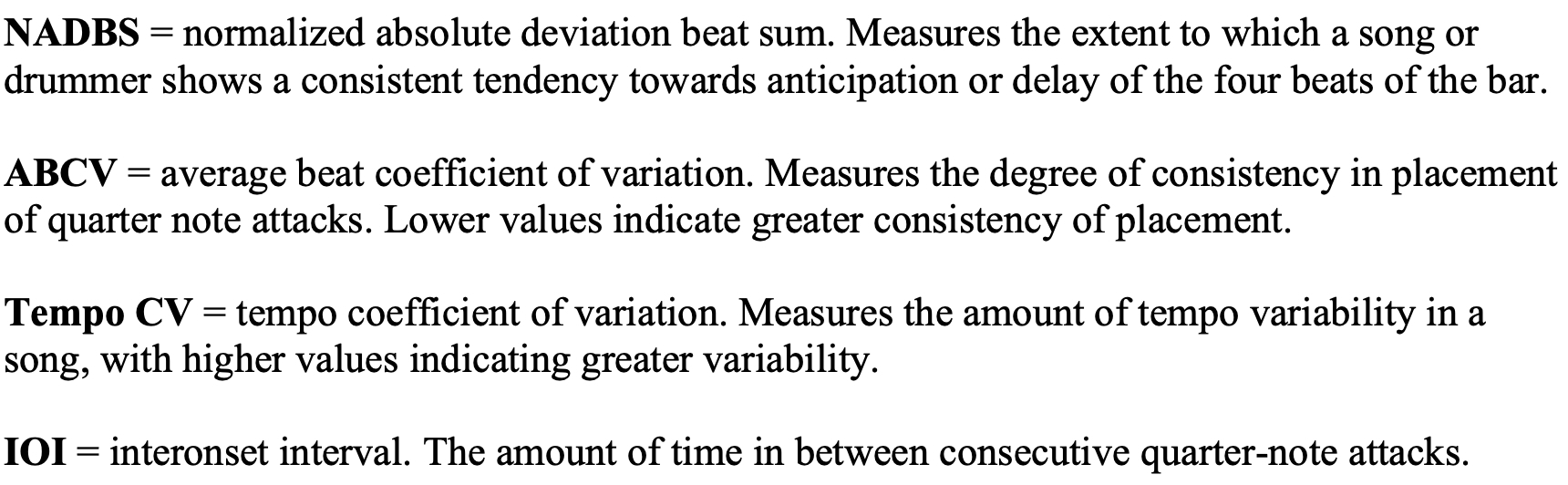

We also made use of two measurements to quantify 1) drummers’ overall tendency towards deviation from isochronous expectation and 2) their tendency towards inconsistency in attack placement. Measuring deviation from isochronous expectation is valuable because it reveals the extent to which a drummer shows a consistent tendency towards delay or anticipation of the four beats of the bar. In order to measure this tendency, we added together the absolute values of the mean deviations (using the previous/accumulated method) for all four beats in a recording, then normalized that value by dividing by the song’s mean IOI.11This measurement is calculated based on means for each beat for the song as a whole. Individual instances of a beat lacking an attack do not interfere with the averaging of all instances of the beat that have an attack. This provided a single number for each song, the normalized absolute deviation beat sum, or NADBS. Figure 3 shows an exemplar calculation of NADBS, for the Beatles’ “With a Little Help from My Friends.” We averaged the NADBS song values for individual drummers in order to provide an overall measure of how much each performer would show patterns of deviation. While other measurements we used account for whether a drummer tends specifically towards late or early attacks, it is also helpful to get a sense of the tendency towards deviation from isochrony in general.

Figure 3: Calculating NADBS (normalized absolute deviation beat sum) for the Beatles’ “With a Little Help from My Friends.”

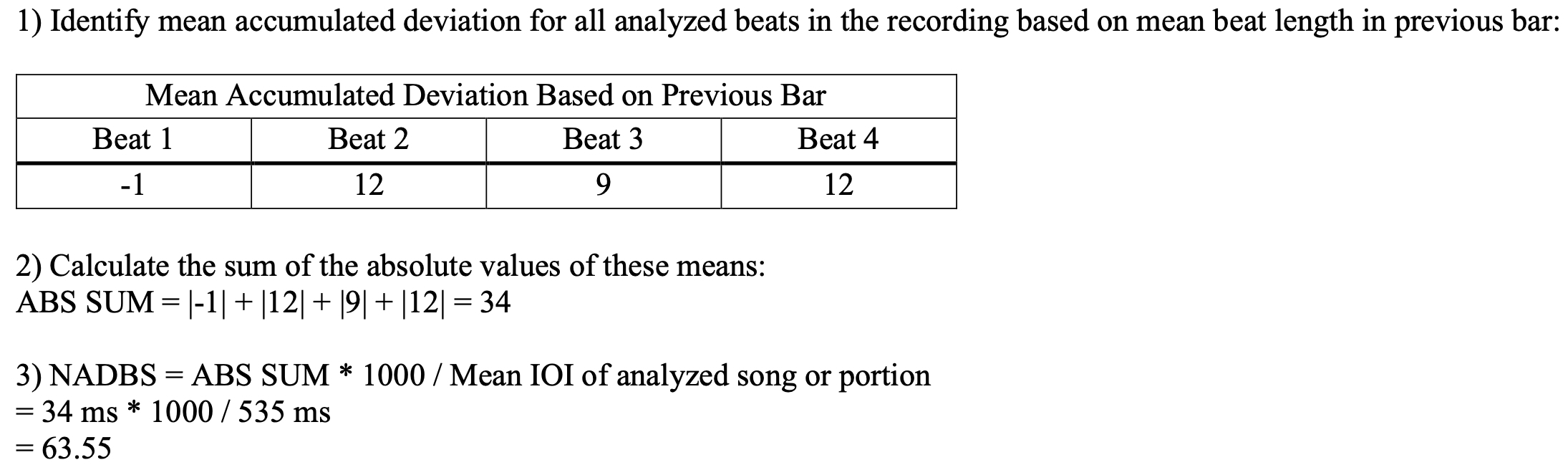

Measuring overall consistency of beat length, on the other hand, provides a sense of the extent to which the drummer replicates a microtiming approach throughout a recording. To generate this value, we calculated the normalized standard deviation of each beat’s interonset intervals, then averaged the resultant four values. This generated another single metric for each song, the average beat coefficient of variation (ABCV).12The ABCV does not rely on either previous-bar or current-bar projections of expected beat placement. It measures the amount of variability with each of the four IOI possibilities in a given song. Figure 4 shows the calculation of the ABCV for the Beatles’ “With a Little Help from My Friends.” For each drummer, we averaged the ABCVs for all of their recordings, generating an overall measure of how consistent they were with attack placement. Lower values indicate greater consistency.

Figure 4: Calculating ABCV (average beat coefficient of variation) for the Beatles’ “With a Little Help from My Friends.”

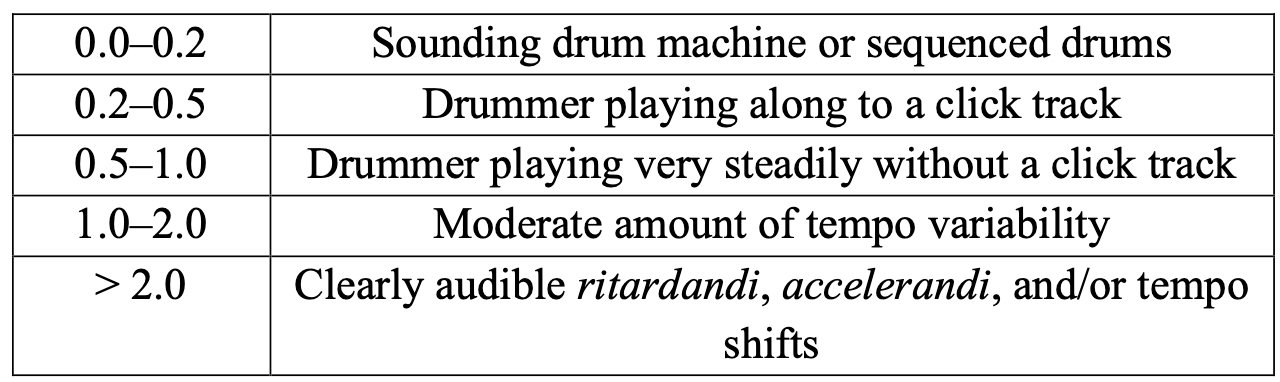

With respect to tempo, we measured both the amount of acceleration or deceleration in each song as well as tempo variability. We used two-bar tempo values in the analyzed portions of the recordings in order to assess the percentage change in tempo from start to end and from start to maximum tempo.13Thus, if a song began with a section without a backbeat variant, the “starting” tempo would be from the start of the portion with the backbeat. To measure tempo variability, we calculated the coefficient of variation (or relative standard deviation) of local tempo measurements within each song (Carter and von Appen 2025a, pp. 125–127). We measured the mean tempo of each set of two bars in a recording, then calculated the standard deviation of those tempo measurements. Dividing the standard deviation by the song’s mean tempo produced a normalized value that we multiplied by 100 in order to express it as a percentage. Tempo coefficient of variation (or “CV”) values calculated in this manner usually range between 0.01 and 5 for a popular song (Carter and von Appen 2025b, pp. 74–77). Figure 5 shows the typical ranges of tempo CV values for different approaches to tempo variability.14These ranges derive from our evaluation of the tempo variability of 423 popular songs in Carter and von Appen 2025b, where we compared tempo CV values with published interviews and other sources documenting whether a click track, sequencer, or drum machine was used on a given recording (pp. 75–77). Our evaluation in this previous study, however, was based on tempo maps of original full recordings created with the software Melodyne, while in the present study CV calculations were instead made using the Moises-derived drum stems, and portions without a backbeat variant were excluded. Therefore, the ranges cited in Figure 5 should be viewed as approximations when compared with the CV … Continue reading CV values do not necessarily reveal whether tempo variability in a given case is intentional or unintentional, though conscious, intentional variability, such as with ritardandi or discrete tempo shifts, tends to result in CV values of 2.00 or higher. Figure 6 provides succinct explanations of tempo CV and of the other acronyms used in this essay.

Figure 5: Approximate ranges of tempo CV values for different approaches to tempo variability.

Figure 6: Meanings of commonly-used acronyms in the text.

Ringo Starr: Delayed Backbeats and Slowing Tempo

Ringo Starr, born in 1940, is the eldest of the five analyzed drummers. Starr played with the Beatles from August 1962 until their final recording session in January 1970. Bruce Springsteen drummer Max Weinberg has argued that the most distinctive elements of Starr’s playing were his use of open hi-hat eighths as well as syncopation in the kick drum (Starr 2015, p. 285; Aronoff 1987, pp. 102–103). Starr is often described as lacking any jazz technique or proclivities in his drumming; his style is often framed as an anti-jazz approach, with avoidance of the ride cymbal a telling characteristic (Starr 2015, pp. 285–287). In this respect he diverges sharply from Mitch Mitchell, who is frequently cited as a drummer heavily influenced by jazz (Altham 2009). Starr is described as a rock drummer, though Weinberg points to country and Latin influences on his playing (Starr 2015, p. 285).

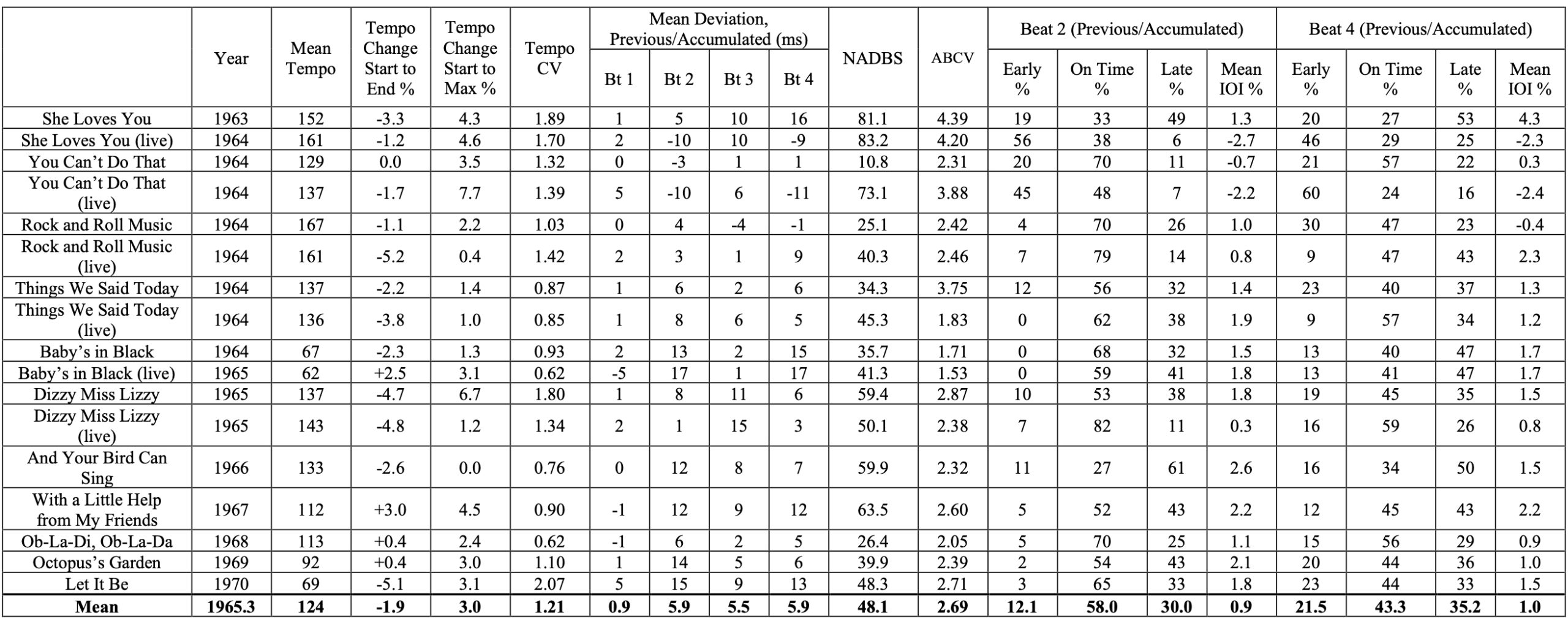

Figure 7: Details of all analyzed Ringo Starr recordings

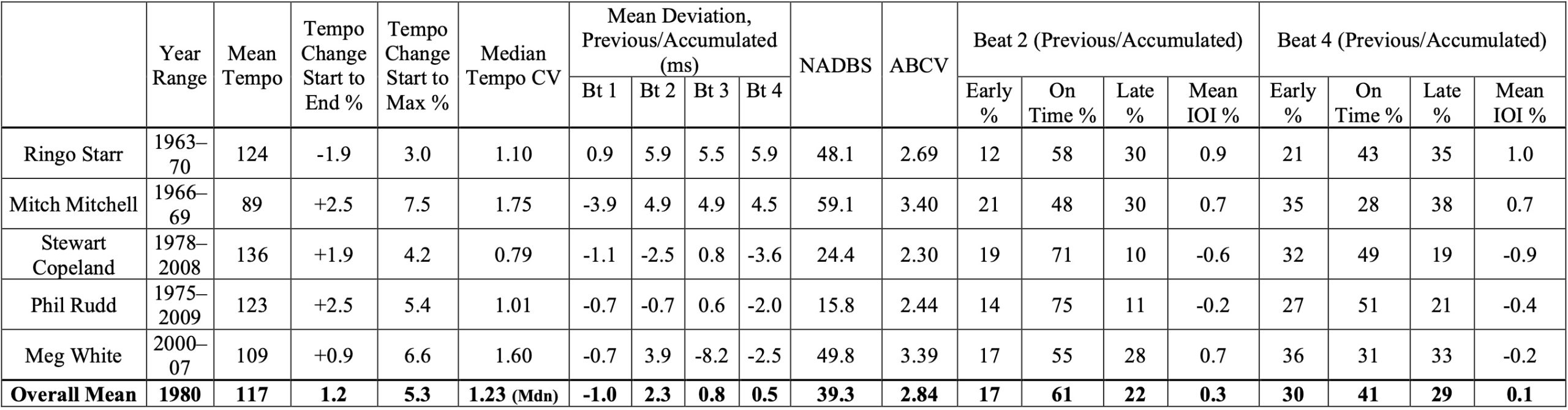

Figure 7 shows the results of our analysis of 17 recordings with Starr. In these recordings, Starr shows very little tendency towards early backbeats, with live recordings of “She Loves You” and “You Can’t Do That” notable exceptions. Instead, he demonstrates a proclivity for backbeat delay, with notable examples of this tendency including “And Your Bird Can Sing” (61% of second beats delayed at least 2.5%), “She Loves You” (49%), “With a Little Help from My Friends” (43%), and “Octopus’s Garden” (43%). As seen in Figure 8, which summarizes the findings for all five drummers, Starr had the highest mean percentage delay of both beats 2 (0.9%) and 4 (1.0%) of the five drummers in our study. Figure 8 contextualizes the statistics for individual drummers discussed below, showing how individual means relate to the others.

Figure 8: Average values for all five drummers.

Figure 9: Mean deviation of beats in the Beatles’ “With A Little Help from My Friends.” On the left are beat-to-beat values measured in comparison with the average beat length of the current bar; on the right are accumulated values, based on the average beat length of the previous bar.

In “With a Little Help from My Friends” (Figure 9), there is a strong tendency for beat 2 to be late. Beat 2 is substantially (2.5% of mean IOI) delayed 43% of the time and substantially early in only 5% of instances. The mean IOIs from 2 to 3 and from 3 to 4 are very close to the bar averages, while the mean IOI from 4 to 1 is relatively small. Thus, as seen in the graph on the right, beats 2, 3, and 4 on average may sound delayed in relation to the downbeat,15The mean IOI from beat 2 to 3 is three milliseconds below average, and there are several beat 3 attacks in the song that are substantially earlier than that. Additionally, the mean IOI from 3 to 4 is three milliseconds above average. So listeners may nevertheless hear numerous third beats as “early.” with the succeeding downbeats arriving relatively quickly in order to keep the tempo from changing too much (though there is a slight acceleration during the analyzed portion of the song, from the beginning of the backbeat pattern at 0:26 to the end). This approach to microtiming is the most common one in the Starr examples we examined, with the averages for the 17 analyzed Beatles recordings reflecting it. As can be seen in Figure 7, for the 17 songs as a group, beat 1 to 2 averages approximately 6 ms of delay; 2 to 3 slightly reduces the accumulated delay; 3 to 4 adds slightly to it; and the IOI from 4 to 1 is small enough that the downbeats on average arrive only slightly behind expectation. Other Beatles songs with a similar profile include “Dizzy Miss Lizzy,” “Things We Said Today” (Live at the BBC,) “And Your Bird Can Sing,” and “Let It Be”(single version). In each case, beat 2 has a high average delay based on previous-bar expectation and 3 and 4 are relatively neutral, with the 4 to 1 IOI small. While this pattern occurred more frequently than any other in the Starr songs we analyzed, it was rare in the other four drummers we studied. It thus can be thought of as an element of Starr’s fingerprint.

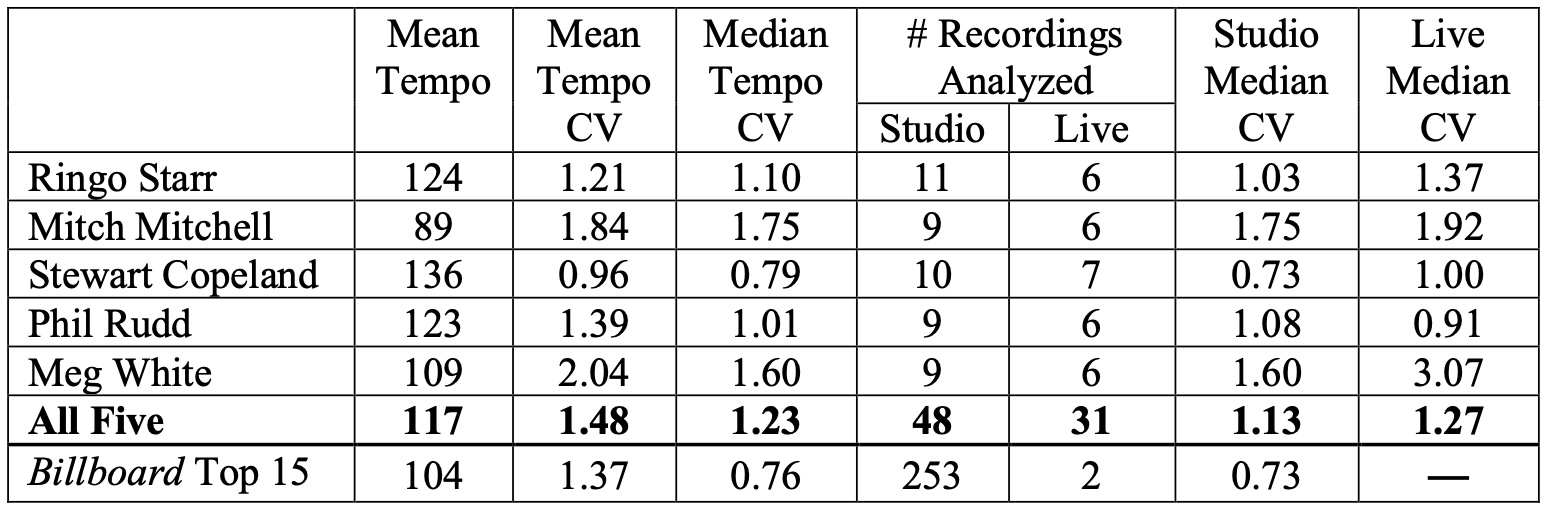

Starr, when assessed for tempo steadiness among the five drummers in the study, is somewhere in the middle. The tempo variability summary chart in Figure 1016Tempo CV values for the five drummers in the study are just for the analyzed portions of the songs, using the isolated drums. “Billboard Top 15” is the year-end top 15 for every other year between 1966 and 1994, with the addition of 1979 and 1995 (see Carter and von Appen 2025b). These values were calculated based on the full recordings.shows that the median CV for Starr’s studio recordings, 1.03, is slightly lower than the median for the five drummers as a group (1.13). The lowest Beatles tempo CVs we found in studio recordings are for “Ob-la-di, Ob-la-da” (0.62) and “And Your Bird Can Sing” (0.76). Examining live recordings is particularly valuable for assessing drummer steadiness, given that studio recordings, even in the era before click tracks, would be more likely to be shaped so as to emphasize tempo stability.17In a studio setting, a band could do many takes and edit together portions of multiple takes in order to achieve greater steadiness on the released recording. The median tempo CV for the six live Beatles recordings we examined is 1.37, in the middle of the five medians for the drummers in our study.18We use medians rather than means for groups of CV values because, given the relatively small number of recordings, a single outlier can have a large effect on a mean value. Tempo CV values themselves are highly sensitive to variability and can be significantly influenced by a single outlier bar in a song. These calculations suggest that Starr is moderately steady compared with others. But because the entire band contributes to tempo variability, the numbers cannot be ascribed solely to him.

Figure 10: Tempo variability means and medians.

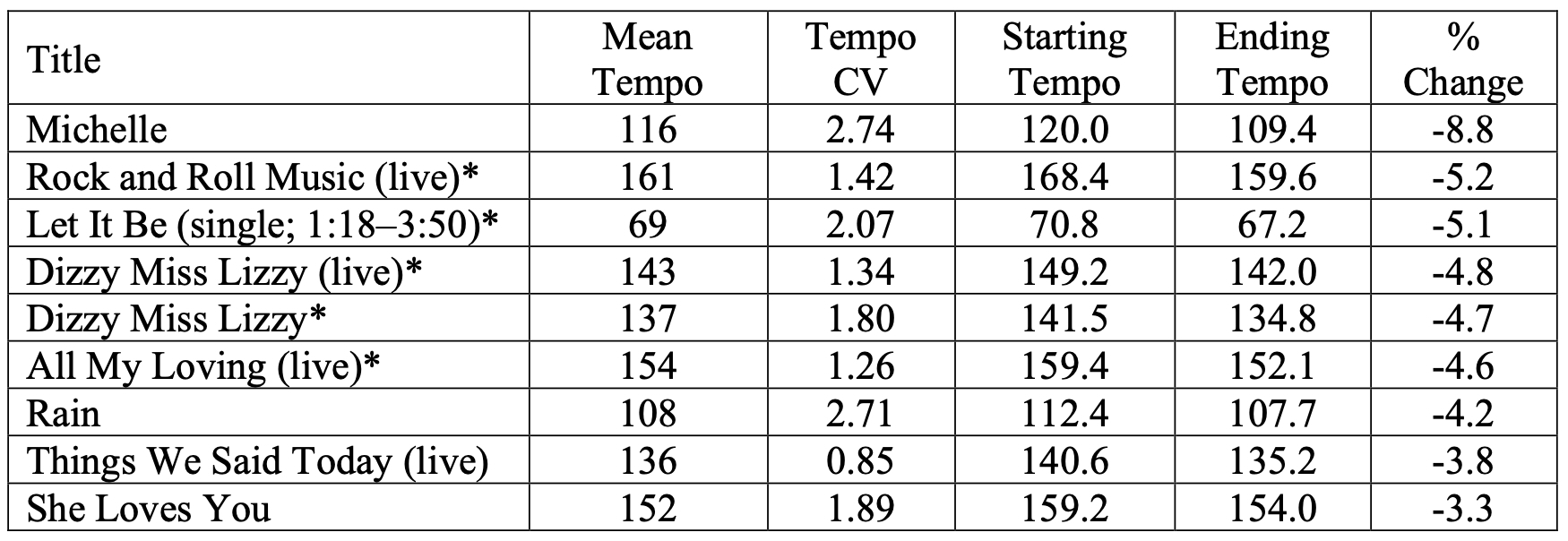

In contrast with, say, the Rolling Stones, who had a pronounced tendency to accelerate within songs in the 1960s and early 1970s (Carter and von Appen 2025a, p. 120 n. 30, 128, 130), the Beatles tended to end recordings at a slower tempo than they started. Figure 11 shows examples of this proclivity, including selected recordings outside of our study. The Beatles still had songs in which they sped up substantially, such as “I’m So Tired,” and accelerating is a general tendency when musicians are performing together in a group (Wolf and Knoblich 2022, pp. 1–2; Thomson et al. 2018, p. 2–3; Okano et al. 2017, pp. 3–4). But more than other prominent rock bands of the 1960s and 1970s, they slowed over the course of recordings (see Carter and von Appen 2025a, pp. 120, 125, 131).

Figure 11: Selected Beatles songs with Ringo Starr that slow down, ordered by percentage reduction in tempo (excluding closing ritardandi). *=Portions with drums analyzed, rather than the full recording. The full “Let It Be” single recording decelerates from 73 to 66 BPM (9.6%) before a closing ritardando.

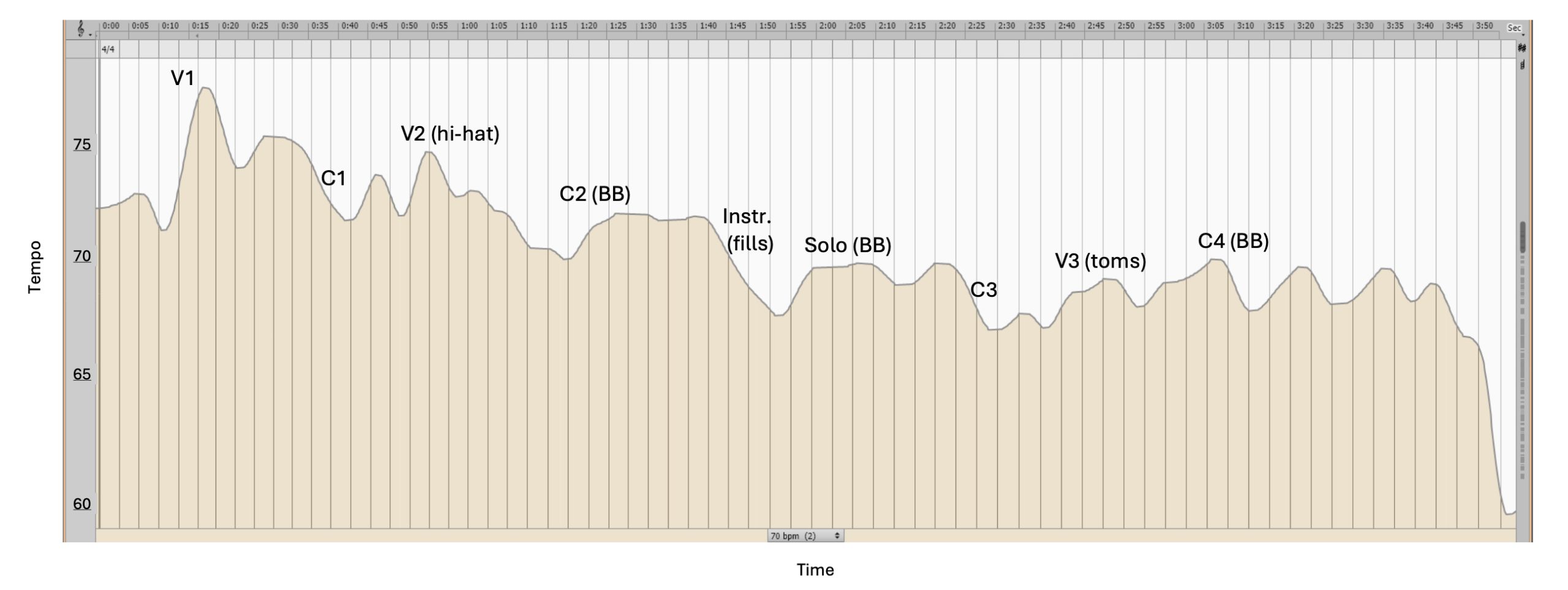

Figure 12 shows a Melodyne tempo map of “Let It Be” (single version), the Beatles recording in our study with the most pronounced slowing.19Celemony’s Melodyne 5 Studio is an audio editing application that, among other features, detects attack transients in order to generate tempo maps. In cases where the automatically generated maps do not exactly match the audio, the user can easily make manual adjustments to correct tracking errors. Here, the passages with the full drum kit and the standard backbeat pattern tend to be relatively steady, while portions without the kit or where Starr is playing an alternate, non-standard pattern tend to slow down. After this slowing occurs and the full kit re-enters, the previous tempo high is not re-attained; instead, the music continues steadily at the slower tempo reached in the previous section. As a result, there is an overall pattern of slowing over the course of the recording. The slowing in “Let It Be” might be associated with the song’s lyrical theme of calm acceptance, a theme potentially at odds with the building energy of many rock tracks. The prominent repeated cadential gestures in the song—especially the recurring decorated double plagal motion followed by a blues V-IV-I cadence—might also be said to fit the slowing tempo. The cadential ritardando at the end of the recording particularly reflects this association of cadential gesture with deceleration. But even at moments in the recording when the texture increases or the chorus arrives, there is not the kind of tempo boost normally associated with these actions in music recorded without a click track (Huron 2006, pp. 323–326).

Figure 12: Melodyne tempo map of the Beatles’ “Let It Be,” showing time on the x-axis and beats per minute on the y-axis. “BB” indicates use of a backbeat pattern in the drums.

Five of the six Beatles’ live recordings that we examined also end at a slower tempo than they begin (Figure 7). Most notably, “Dizzy Miss Lizzy” starts at 149 and ends at 139 BPM. Slowing also occurs in the studio version of the song, with the tempo starting at 142 and ending at 134 BPM. The Beatles’ BBC performance of “Rock and Roll Music” also ends substantially slower than it begins, starting at 168 and ending at 159 BPM. Starr is steadier in live versions of “Baby’s in Black” and “She Loves You” recorded at the Hollywood Bowl (1964–65).

This tendency towards slowing is part of Starr’s fingerprint. His proclivity for delayed backbeats is similar to that of his counterpart Charlie Watts of the Rolling Stones and could be a generational tendency. But his slowing of tempo in many recordings contrasts with most other rock drummers past and present. The combination of delayed backbeats and slowing of tempo together suggest a more laid-back approach to drumming that seems particularly suited for Beatles’ ballads like “Let It Be” and “Baby’s in Black.”

Mitch Mitchell: Early and Late Attacks, Building Tempo

Mitchell’s “tsunami”-like drumming (Stubbs 2008) embraces variability of attack placement as artistic expression. It complements the distortion and freedom of Jimi Hendrix’s guitar playing, with the “raucous” aspects of both (Griffith 2009, p. 36) an expression of psychedelic possibilities and rebellion against the bourgeois values of the previous generation’s “silent majority.” Discussions of Mitchell often mention the influence that jazz had on his playing, including allegedly lending a triplet feel to his timing and thereby creating a straight-eighth/swing hybrid (Altham 2009; Griffith 2009, pp. 35–36). He often avoids a standard backbeat pattern and substantially embellishes it when he does use one. His drumming has a more active and “melodic” approach than most other rock drummers, though he disdained soloing per se (Altham 2009; Griffith 2009, p. 39). Mitchell incorporates frequent fills and also embellishes his kick drum patterns with syncopation, as can be heard, for example, in “Little Miss Lover.” The slower tempos in the Hendrix songs in our study (with the mean tempo shown in Figure 8 much lower than that for the other four drummers) are combined with relatively fast and frequent fills, providing rapid rhythmic activity within that overall slower pulse. Mitchell’s frequent use of fills and syncopation presents challenges for our method of analysis, which is based around looking at quarter-note attacks. Yet we were able to identify a number of passages where we could apply our method.

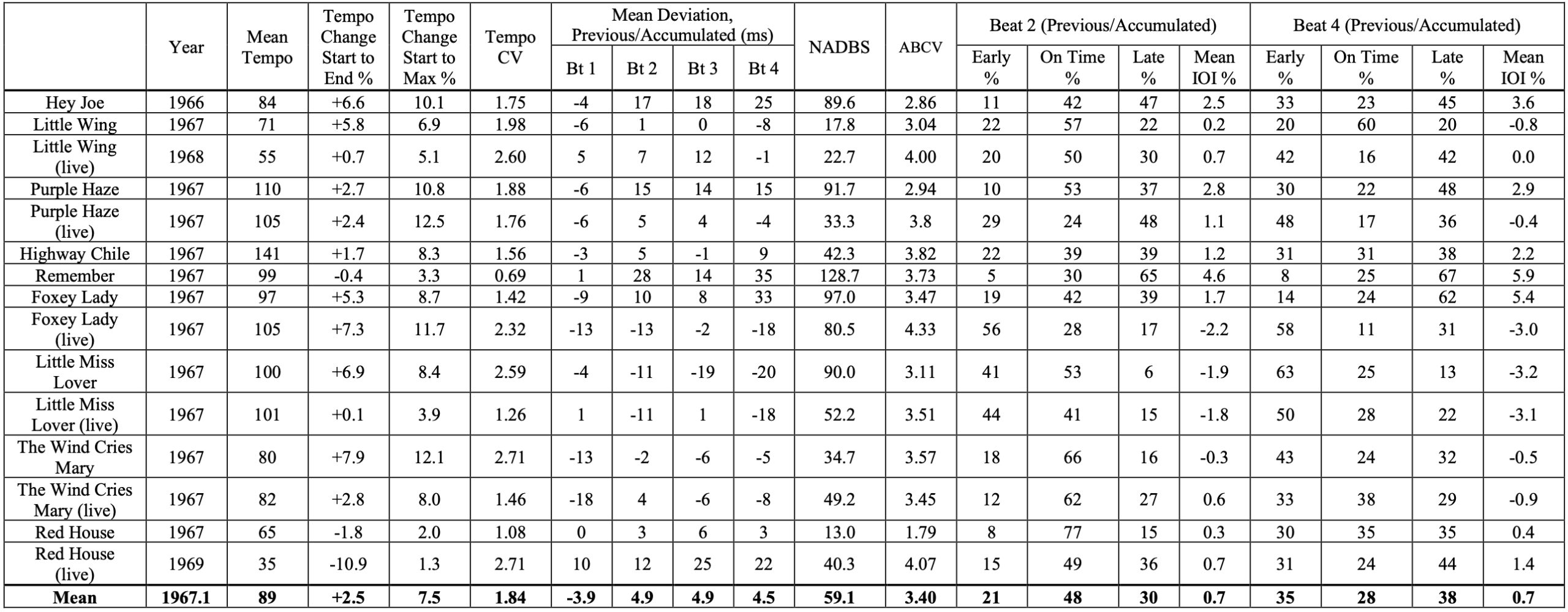

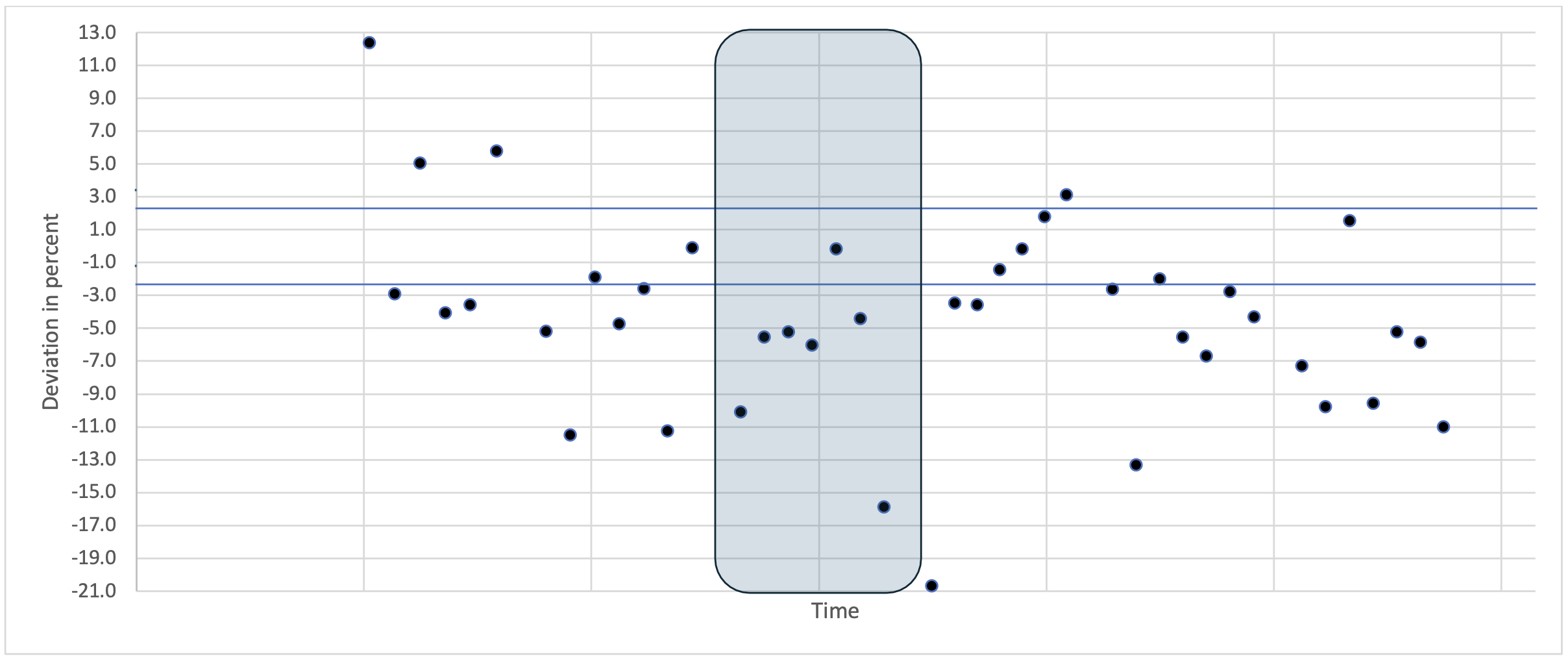

Mitchell shows the greatest tendency among the five studied drummers for both early and late backbeats as well as the least consistency of attack placement. Mitchell has the lowest percentage of beat 2 (48%) and beat 4 attacks (28%) that fall within 2.5% of the average IOI of the songs in question. Mitchell’s tendency towards both early and late backbeats is in some cases manifested in the same recording, such as in live versions of “Little Wing” and “Purple Haze” and the studio recording of “Highway Chile” (Figure 13).

Figure 13: Details of all analyzed Mitch Mitchell recordings.

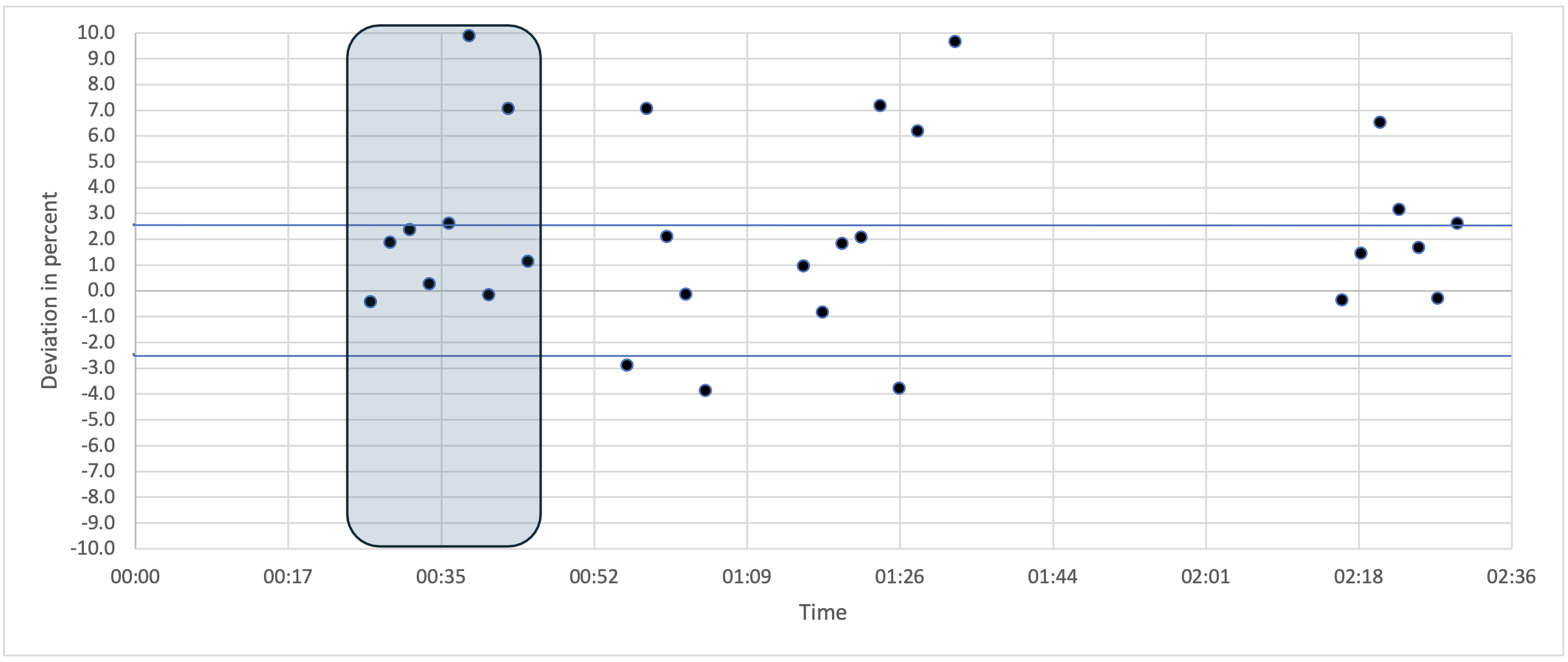

His lack of consistent attack placement is evidenced by his average beat coefficient of variation (ABCV) of 3.40, the highest among the drummers studied (Figure 8). There are some recordings, however, where he sided more with either early or late backbeat placement. A live version of “Foxey Lady”20The song was titled “Foxy Lady” on the original U.K. release of the album Are You Experienced, then retitled “Foxey Lady” for the U.S. album and single. and both the studio and live versions of “Little Miss Lover” decidedly favour early backbeats, while Mitchell shows strong tendencies towards backbeat delay in the studio versions of “Remember,” “Hey Joe,” and “Purple Haze.” Figure 14, accompanied by the audio excerpt in Media 2, shows the microtiming of all the analyzed second beats in “Purple Haze” as a percentage of mean IOI. The amount of displacement from expectation varies, but the number of early attacks is much smaller than the number of late ones and there are seven attacks that are at least 6% of mean IOI late.21We use mean delay rather than median when analyzing attack placement because extreme values have a real effect on the listener. In our listening experience, even a relatively small number of very late attacks combined with others near average can give a sense of delay.

Figure 14: Deviation of beat 2 as a percentage of mean IOI in the Jimi Hendrix Experience’s “Purple Haze.” The highlighted area corresponds to the audio excerpt.

Media 2: Isolated kick and snare drum from the Jimi Hendrix Experience’s “Purple Haze” (0:23–0:37). Here, beat 1 is mostly slightly early, while beats 2, 3, and 4 are mostly delayed. Listen to Media 2.

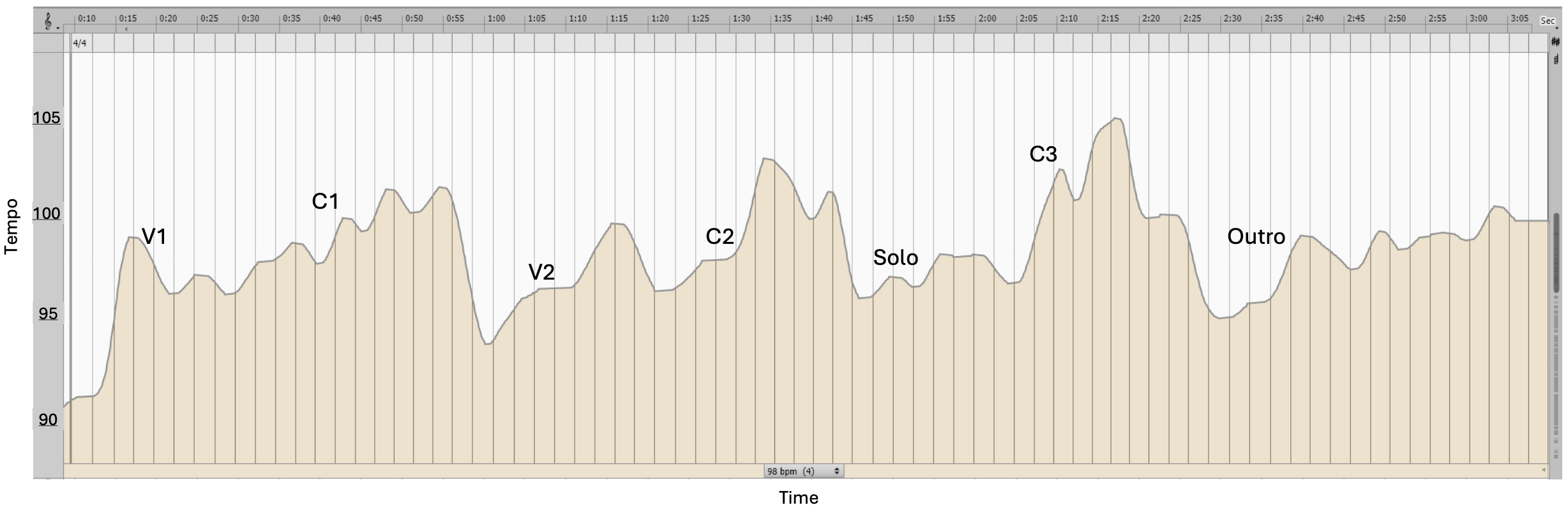

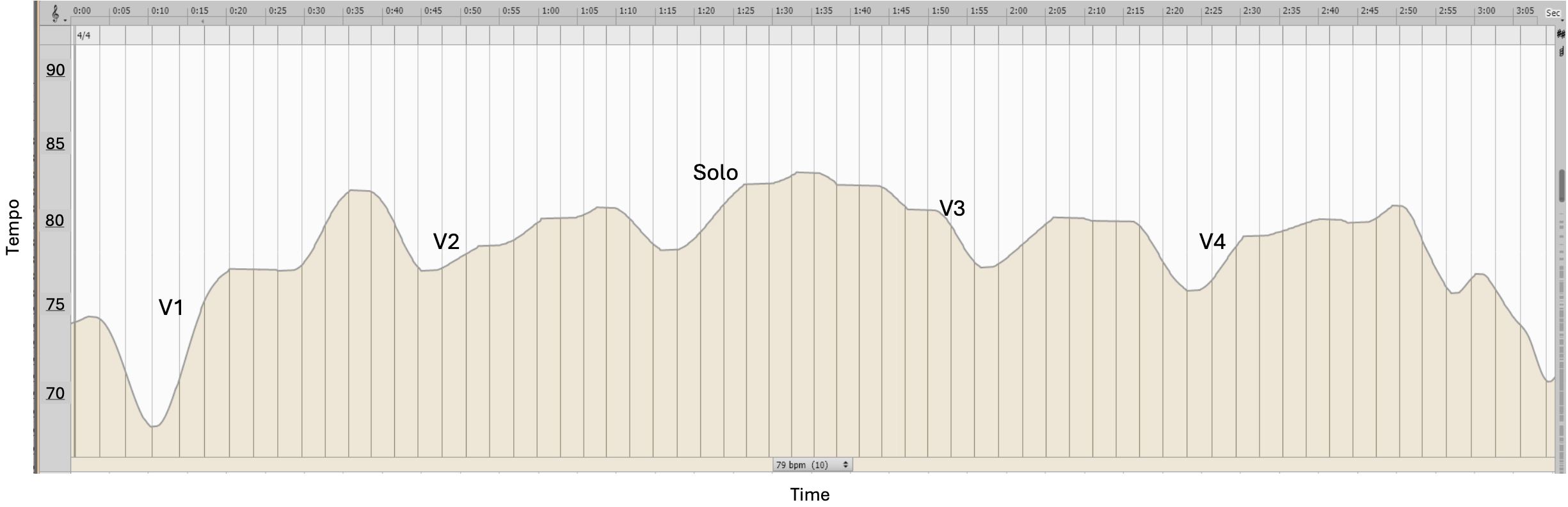

Mitchell has often been described as having a “loose time feel” (Griffith 2009, pp. 39–40), and the tempo variability numbers in our study back up these claims. The median tempo CV in his recordings is the highest of the five studied drummers (1.75; Figure 10). As seen in Figure 8 above, Mitchell shows a greater tendency to accelerate than any of the other four drummers. The studio version of “Foxey Lady” is one of the steadier Mitchell tracks we analyzed, with a CV of 1.42 for the examined portion, but still shows substantial variability. As seen in the Melodyne tempo map in Figure 15, it has an overall pattern of acceleration from 92 to 96 BPM, but the tempo along the way reaches as high as 105 BPM at 2:16. There is a clear pattern of building from the start of each verse to the end of each chorus before the tempo drops back down again. A similar acceleration occurs during the guitar solo, starting at 1:47. Other Hendrix tracks with Mitchell, such as “The Wind Cries Mary,” “Little Miss Lover,” and live versions of “Red House” and “Little Wing,” also show relatively large tempo variability (Figure 13). In “The Wind Cries Mary” (Figure 16), similarly to “Foxey Lady,” the tempo gradually builds during each verse until the refrain is reached, at which point it falls back before reascending during the next verse. The intro and outro are both rhythmically freer and slower than the rest of the recording.

Figure 15: Melodyne tempo map of the Jimi Hendrix Experience’s “Foxey Lady.”

Figure 16: Melodyne tempo map of the Jimi Hendrix Experience’s “The Wind Cries Mary.”

Our findings with respect to microtiming and tempo variability seem consistent with descriptions of Mitchell’s playing: the looseness of his attack placement and expressive tempo variability are manifest in our calculations. These characteristics are as much a part of his fingerprint as his frequent use of syncopation and fills. His drumming in all these respects complemented Jimi Hendrix’s adventurous and virtuosic guitar work and contributed to the psychedelic aesthetic that the band cultivated.

Stewart Copeland: Early Backbeats and Steady Tempo

Discussions about the playing of Stewart Copeland focus above all on his integration of reggae with rock drumming. While Copeland would frequently employ a reggae pattern with no kick on beat 1 in the verses of Police songs, Aukofer nevertheless notes that the most commonly-used drum pattern on the Police’s Reggatta de Blanc album is what he calls a “driving rock pattern,” a backbeat variant where the kick also has a pickup eighth note and syncopation on the “and” of beats 1 and 3 (2011, pp. 12, 86). Copeland particularly uses this pattern in prechoruses and choruses (pp. 44, 67, 105). He incorporates influences from Arabic music (pp. 5, 105) and makes distinctive use of the hi-hat and splash cymbals (Micallef 2018, pp. 27, 31; Aukofer 2011, pp. 37–38, 106–107). Copeland learned jazz drumming at an early age, yet claims that he has had no interest in such an approach as an adult (Copeland 2009, p. 183). In contrast with Mitch Mitchell, also thought to be influenced by jazz, Copeland is described as a groove-based drummer, avoiding extensive fills or soloistic playing (Aukofer 2011, p. 5).22Jazz influence in drumming is often associated with taking more liberties, variation, and flexibility. See, e.g., Mattingly 1998, p. 13.

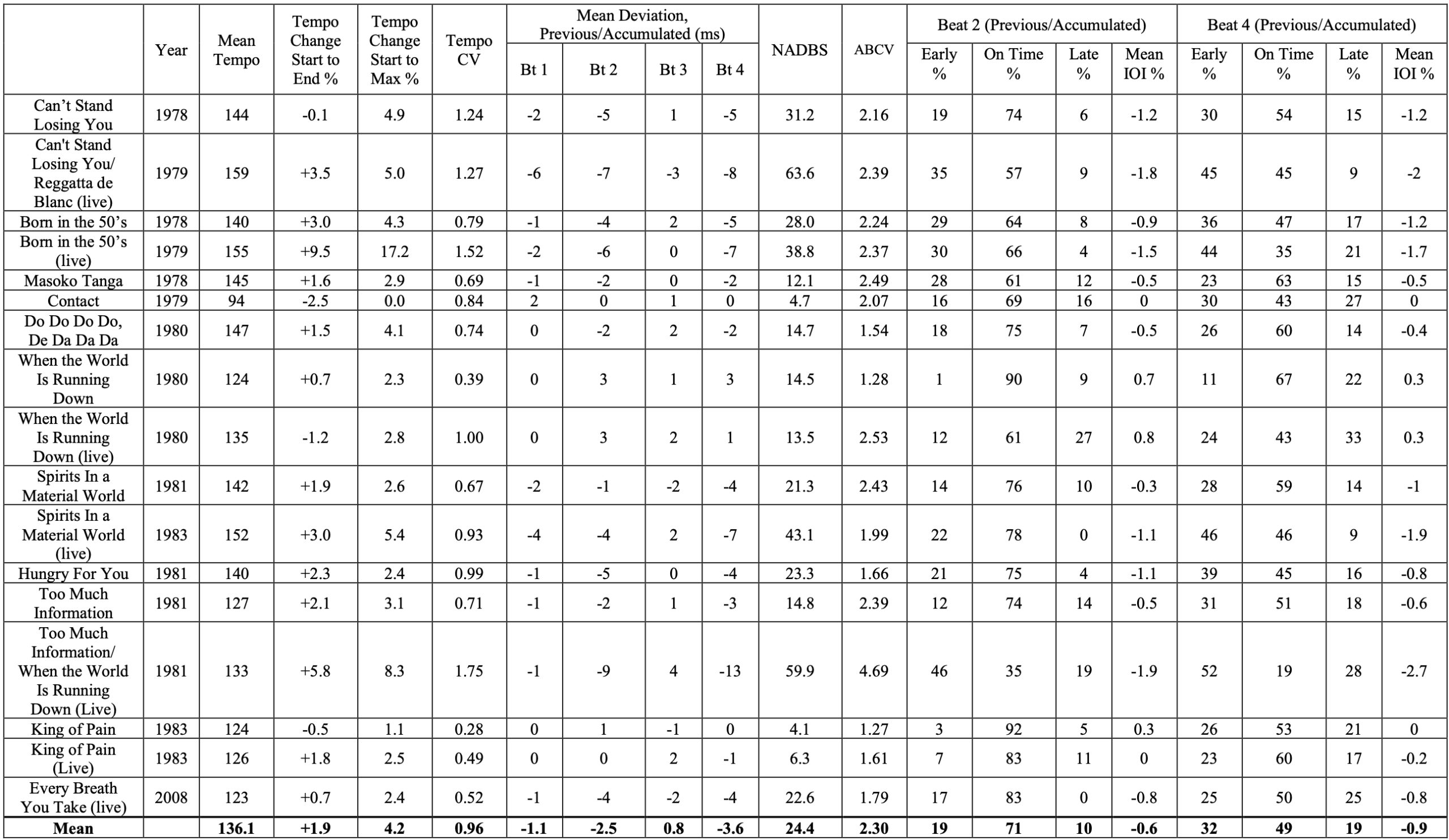

Figure 17: Details of all analyzed Stewart Copeland recordings.

Copeland overall has smaller microtiming deviations than those of the other drummers we studied except for Phil Rudd (Figure 8 and Figure 17). He has, after Rudd, the second greatest percentage of beat 2 and 4 attacks that are on time (within 2.5% of expectation). In addition to having relatively small deviations from expectation, Copeland’s cumulative average beat coefficient of variation (ABCV) of 2.30 is lower than that for any other drummer we studied. This is an indication of consistent attack placement—relatively small variability from the mean deviations for each beat in a song.

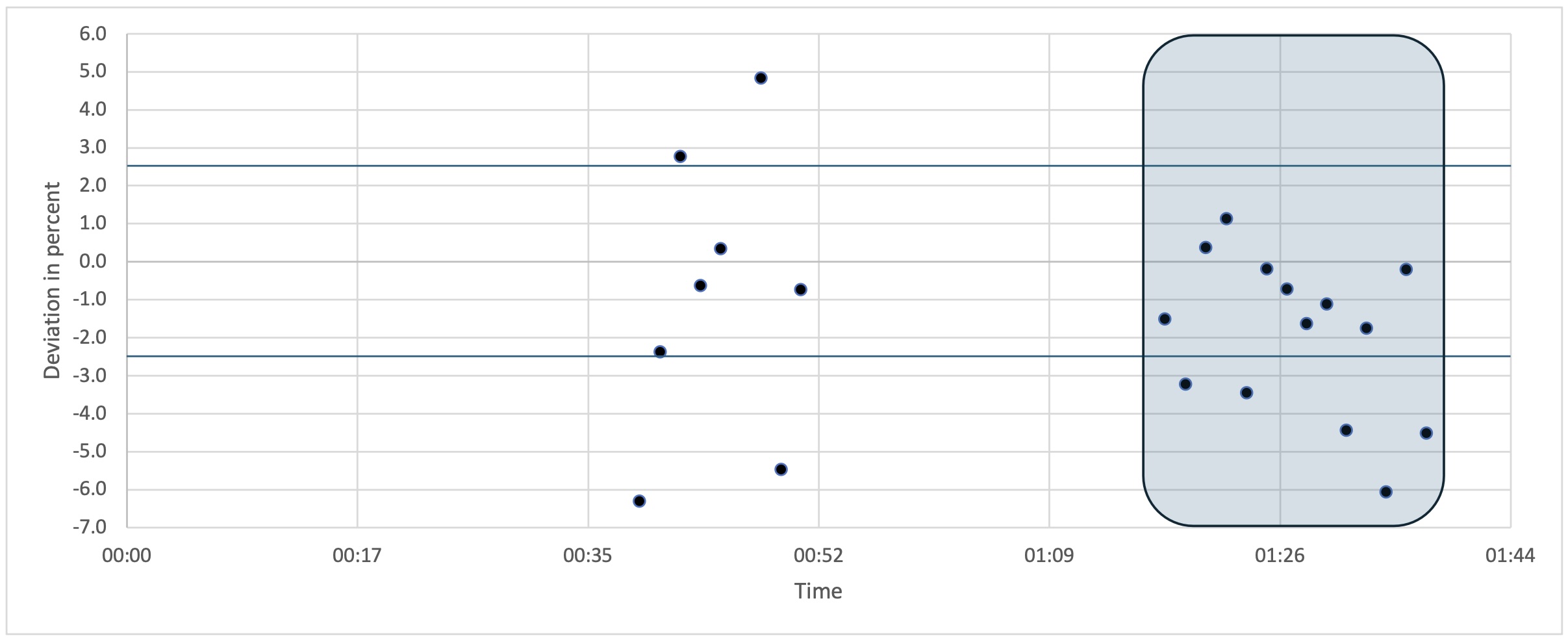

While Copeland’s microtiming deviations overall were small, he showed a clear preference for early backbeats over delayed ones. Consistent with his reputation for playing ahead of the beat, he has a negative average for both beat 2 (-0.6%) and beat 4 (-0.9%) placement, indicating a tendency towards playing these early. Copeland and Phil Rudd were the only two of the five drummers we studied with negative averages for both beats 2 and 4, and in the case of Rudd this tendency was much smaller. Copeland was the least likely of the five drummers to substantially delay beats 2 and 4. Copeland tracks with the greatest tendency towards an early beat 2 include a live “Too Much Information/When the World Is Running Down” medley with 46% of beat 2 attacks substantially early, the opening portion of the “Can’t Stand Losing You”/“Reggatta de Blanc” medley performed live on Countdown in 1979 (35%), and “Born in the 50’s,” live in Bremen, 1979 (30%). Figure 18 shows Copeland’s beat 2 attacks in the opening “Can’t Stand Losing You” portion of the 1979 Countdown medley.23The “Reggatta de Blanc” portion of the medley does not use a backbeat pattern or variant.

Figure 18: Deviation of beat 2 as a percentage of mean IOI in the Police’s live medley of “Can’t Stand Losing You”/“Reggatta de Blanc” (from the start of the recording until the start of the “Reggatta de Blanc” portion). The highlighted area corresponds to the audio excerpt.

Media 3: Isolated kick and snare drum in an excerpt from the Police’s “Can’t Stand Losing You/Reggatta de Blanc” medley (live on Countdown, 1979) (1:16–1:42), with early snare hits on beat 2. Listen to Media 3.

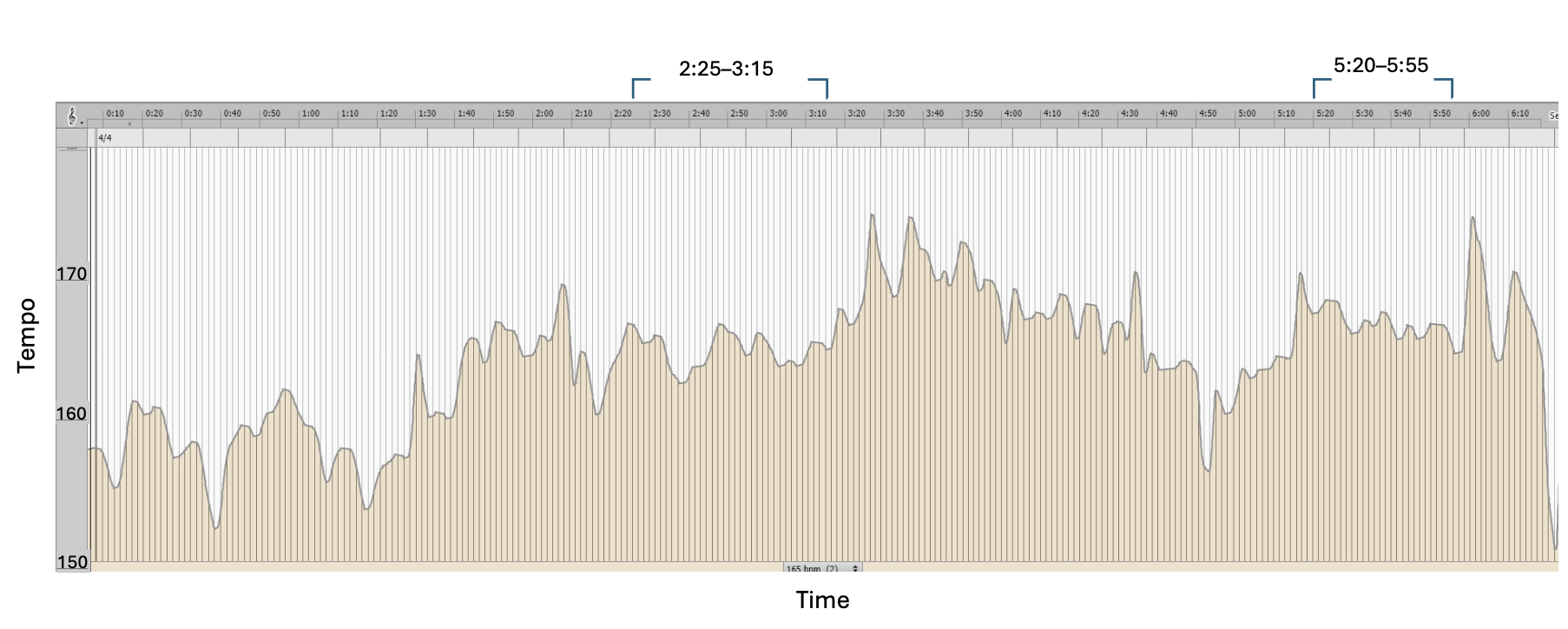

While some have claimed that Copeland tends to rush (Micallef and Marshall 2007, p. 28; Micallef 2018, p. 27), he exhibited greater tempo steadiness in studio recordings than the other four drummers studied. As seen in Figure 10, the median tempo CV for his 15 analyzed recordings is 0.79, with a median of 0.73 for studio recordings and 1.00 for seven examined live recordings. This steadiness is in part the result of Copeland playing along to a click track in some studio recordings (and sequencing or click tracks in some live settings), along with the greater preference for tempo steadiness in pop in the late 1970s/early 1980s period in which the Police recorded (Carter and von Appen 2025b, p. 83–85). Copeland studio recordings with CV values that suggest use of a click track or overdubbing a drum machine (ranging between 0.2 and 0.5) include “King of Pain” (1983, 0.28), “When the World Is Running Down” (1980, 0.39), and, outside of our corpus, “Every Breath You Take” (1983, 0.22, on which an Oberheim DMX drum machine supplied the kick and Copeland overdubbed snare drum, hi-hat and cymbals; Flans 2004). The Police 1983 Oakland live version of “King of Pain” has a tempo CV of 0.49, higher than the 0.28 of the studio version of the song but also within a range typical for use of timekeeping assistance.24Audio and video of the performance (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ak_gxPfSEfg) show that a sequenced eighth-note percussive ostinato runs throughout nearly the whole song, maintaining tempo stability. Copeland’s use of a click or sequence also contributes to the relatively small microtiming deviations in his playing.

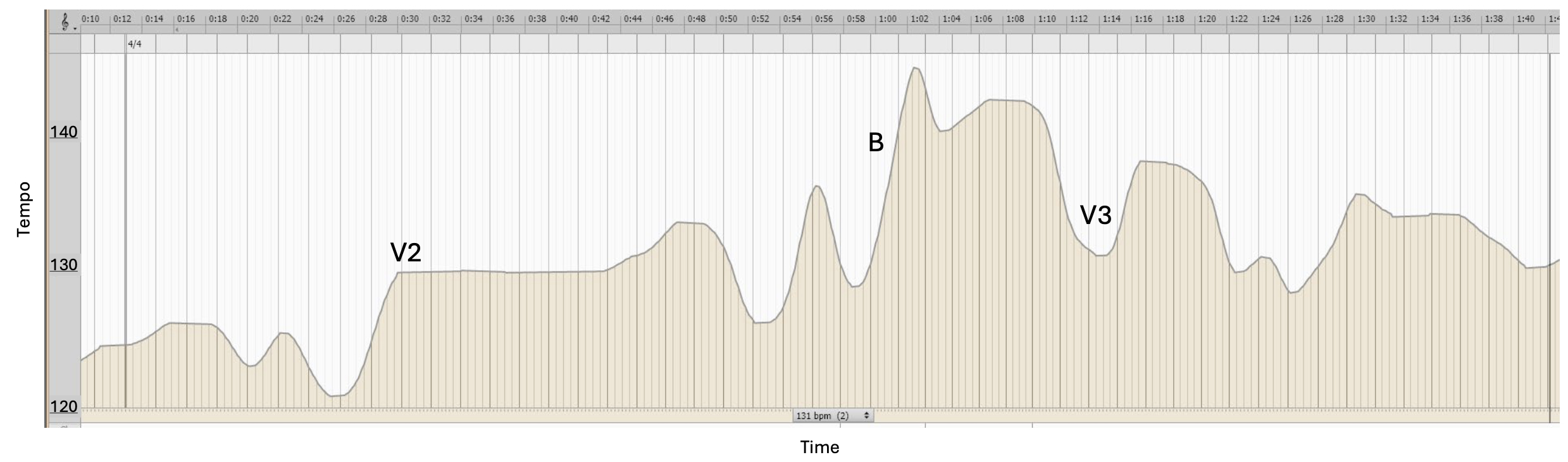

Even when not performing with a sequence or click track, however, Copeland still shows relative steadiness and precision of attacks. His live tempo CV values are not nearly as low as those in studio recordings, yet his live median CV of 1.00 ranks second among the five analyzed drummers, after Rudd. “Spirits in a Material World” (live, Oakland 1983), though it accelerates from 147 to 157 by the end, has a tempo CV of 0.93, a reasonably steady value for a live performance. The Police’s live medley of “Can’t Stand Losing You” and “Reggatta de Blanc” (on Countdown, 1979) has multiple extended passages that are very steady, including 2:25–3:15 (with the tempo ranging between 163 and 167 BPM) and 5:20–5:55 (with the tempo ranging between 164 and 166 BPM). Figure 19 shows a tempo map for this recording. Other portions of this recording show greater variability, but the variability in these sections correlates logically with song structure and with changes in the musical texture. There is a gradual building of the tempo from 156 BPM until a high point of tempo, texture, and energy is reached at 3:25 with a tempo of 176 BPM. During the breakdown that follows, the tempo recedes a bit for the final verse and chorus before rebuilding again for the high-energy outro.

Copeland’s defining characteristics are a tendency towards early backbeats and relative steadiness of tempo. Claims that he tended to rush have some basis in fact, but seem exaggerated, with his early backbeats perhaps misconstrued by listeners as rushing. Copeland’s drumming reflects both the era in which the Police played and the new wave aesthetic of the band, with its mélange of disco and reggae influences demanding a different approach than the laid-back style of Starr and Charlie Watts.

Figure 19: Melodyne tempo map of the Police’s live performance of the medley “Can’t Stand Losing You”/”Reggatta de Blanc.”

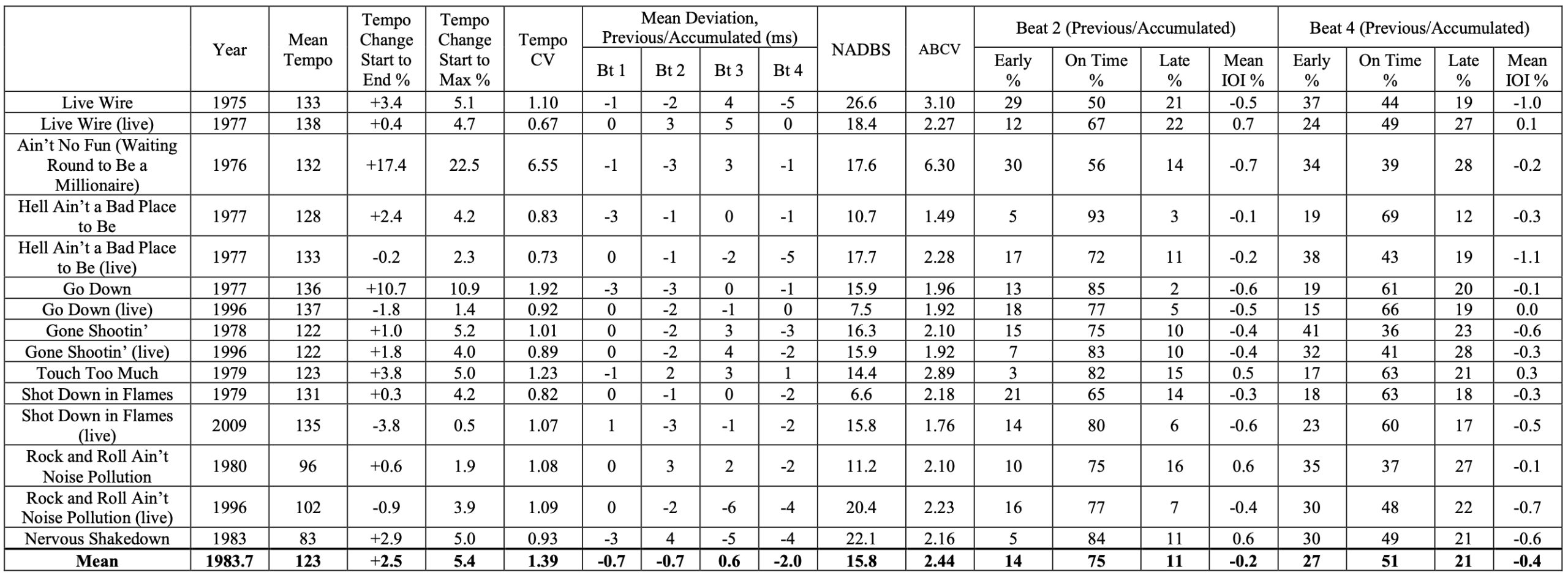

Phil Rudd: Precision Without a Click

Commenters on AC/DC’s Phil Rudd’s drumming characterize it as “simple” and his timing as very “tight” (Kaufmann 2010, pp. 78, 80). As seen in Figure 8 above, the most noticeable features of microtiming in his playing are the small amounts of variance from expectation and the relatively small deviations from means for each beat. Figure 20 shows our detailed findings for the 15 recordings with Rudd that we analyzed. Rudd has the lowest normalized absolute deviation beat sum (NADBS) of the five drummers in our study, indicating that he plays with very little consistent tendency towards delay or anticipation. His ABCV of 2.44 is the second lowest after Stewart Copeland, reflecting great consistency of attack placement. His minimalistic playing style, with relatively few embellishments, is matched by precision and consistency of timing and tempo.

Figure 20: Details of all analyzed Phil Rudd recordings.

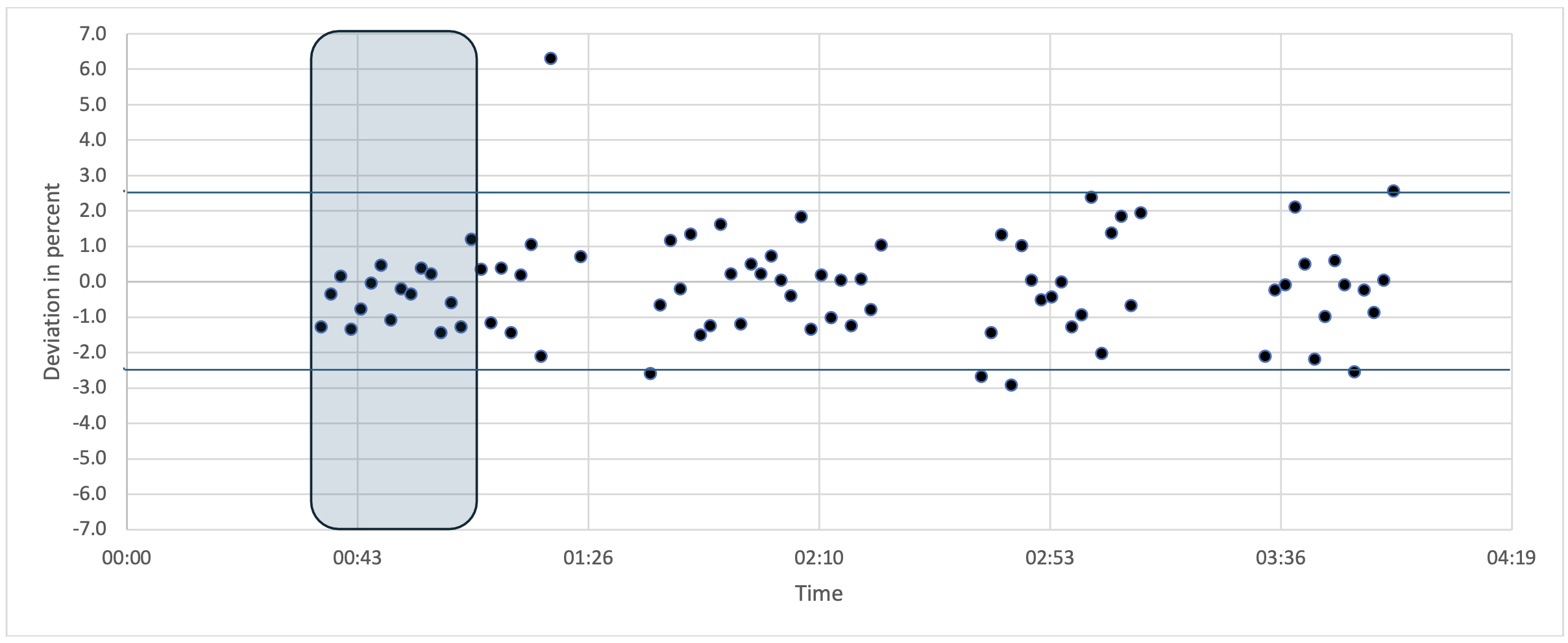

Rudd’s percentages of beat 2 and beat 4 attacks within 2.5% of expectation are higher than those of the other four studied drummers, further reflecting his tendency towards playing precisely on the beat. In “Hell Ain’t a Bad Place to Be,” 93% of Rudd’s beat 2 attacks occur within 2.5% of expectation based on the prior bar, the highest value of any of the 79 songs in our study. Figure 21 shows each of these attacks, with the vast majority falling between the blue horizontal lines indicating the 2.5% and -2.5% thresholds. Unlike Copeland, Rudd displays no consistent tendency towards playing beat 2 early.

Figure 21: Deviation of beat 2 as a percentage of mean IOI in AC/DC’s “Hell Ain’t a Bad Place to Be.” The highlighted area corresponds to the audio excerpt.

Media 4: Isolated kick and snare drum from AC/DC’s “Hell Ain’t a Bad Place to Be” (0:34–1:02), demonstrating very precise timing. Listen to Media 4.

With respect to tempo variability, Rudd is known for being able to play extremely steadily without relying on a click track (Kaufmann 2010, p. 78). Our analysis supports these claims. The median tempo CV for his 15 analyzed releases is 1.01, the lowest of any of the five drummers studied except for Stewart Copeland. Rudd produces some relatively low tempo CV values that are slightly outside the range typical of click track use, including the 1977 Atlantic Studios live versions of “Hell Ain’t a Bad Place to Be” (0.73) and “Live Wire” (0.67).25A 2020 AC/DC recording outside our study, “Shot in the Dark,” however, has a tempo CV of 0.27, suggesting that Rudd likely recorded to a click at least in this one much more recent case. There are also Rudd recordings, however, with tempo CV values not nearly as low, such as the studio versions of “Ain’t No Fun (Waiting Round to Be a Millionaire)” (6.55), “Go Down” (1.92), and “Touch Too Much” (1.23). But the variability in these recordings occurs in a controlled, intentional fashion. The high CV value for “Ain’t No Fun” results from its use of two contrasting tempos (Figure 22). In the first half of the song, there is a gradual acceleration that complements the build in texture. After the intro, this opening half of the recording contains a series of verses on an open D chord, building in tempo until a series of refrains with both a faster harmonic rhythm and faster tempo. The orchestration of the drums also reflects this formal shift, using a closed hi-hat in the first half and open, ringing cymbals in the second half of the recording.

Figure 22: Melodyne tempo map of AC/DC’s “Ain’t No Fun (Waiting Round to Be a Millionaire).”

Like his band, Rudd thus balanced on the line between “authentic,” wild bluesiness and carefully polished, commercially viable professionalism. At least between 1975 and 1983, his approach to microtiming and tempo could be so precise as to be almost machine-like, yet the band avoided perfect alignment with a grid.

Meg White: Wide Variability in Timing and Tempo

Commenters on Meg White’s drumming, including her bandmate Jack White, have claimed that she played in a “childlike,” “simplistic,” or “amateurish” manner (Toews 2023; Djupvik 2017, p. 185; Mack 2015, p. 183). To some extent, such statements correlate with the White Stripes’ frequent references to childhood and simplicity in their lyrics, music, apparel, and stage decoration: the duo recorded songs like “I Want to Be the Boy to Warm Your Mother’s Heart,” “We’re Going to Be Friends,” and “You’re Pretty Good Looking (For a Girl)” and used candy cane stripes in their branding and as the inspiration for their band name. Some, however, have critiqued Jack White’s infantilization of Meg (Eells 2012). And her “simple” approach is thought to have allowed her more “power” (Toews 2023). She is said to have effectively left “space” in the musical texture, leaving out elements of a drum pattern rather than constantly playing everything. She would start with a simple texture and gradually add rhythmic elements or drum kit components over the course of the song. White Stripes songs are known for exploring multiple feels and tempos in the same recording (Toews 2023).

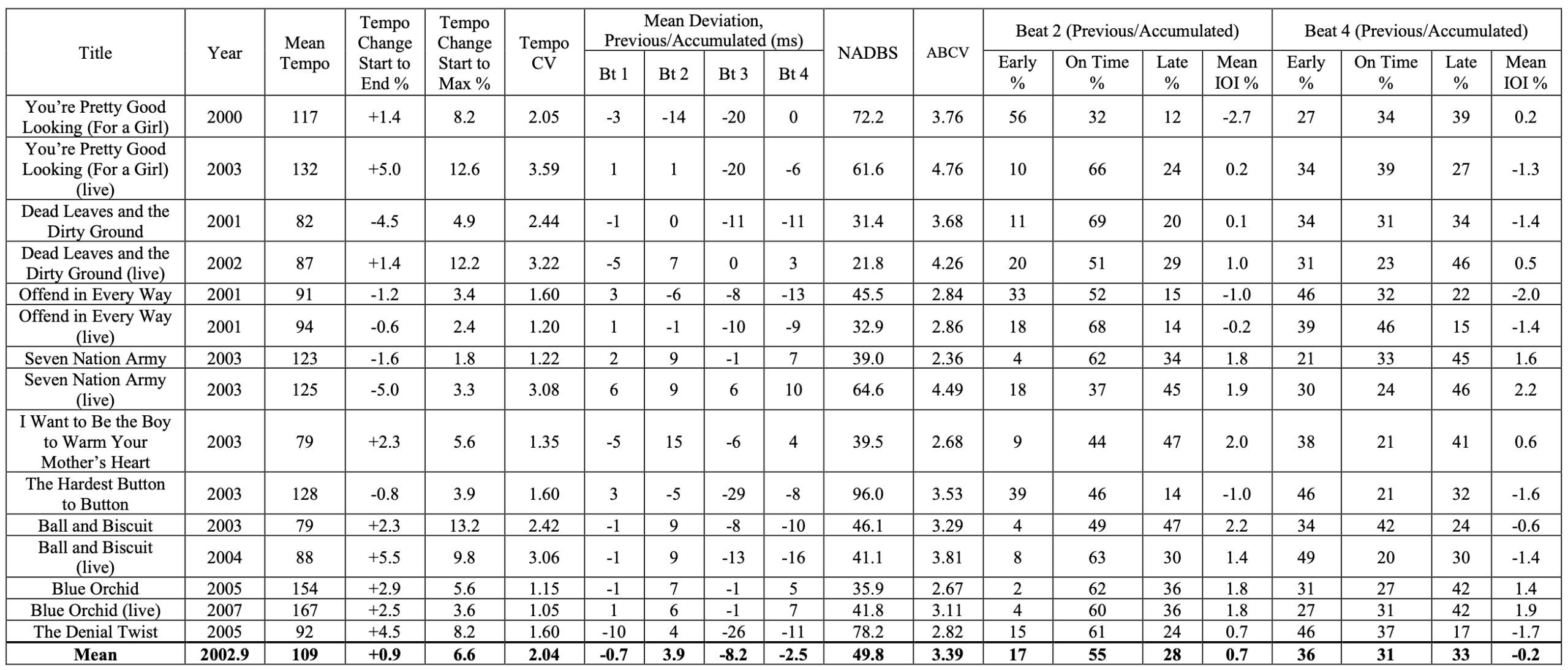

Figures 23 and 8 show that White’s quarter-note attacks feature asymmetric division of the bar, high standard deviations of beat attack placements (as reflected in ABCV), and high tempo coefficients of variation. White’s combined deviations from expectation, measured by her NADBS value of 49.8, are the second highest in our study, after Mitch Mitchell. This NADBS value results primarily from White’s tendencies towards a delayed beat 2 and a very early beat 3. White tracks with a particularly early beat 3 include “The Hardest Button to Button,” “The Denial Twist,” and both the studio and live versions of “You’re Pretty Good Looking (For a Girl).” Figure 24 shows all analyzed beat 3 attacks in the live 2003 TIM Festival version of the latter song. This strong tendency towards an early beat 3 distinguishes White from Mitchell as well as the other drummers studied.

Figure 23: Details of all analyzed Meg White recordings.

White’s attacks on beats 2 and 4 tend to deviate significantly from expectation in both directions. After Mitch Mitchell, she has the second lowest percentage of backbeat attacks that fall within 2.5% of mean IOI (Figure 8). She shows a propensity for early backbeats in “You’re Pretty Good Looking (For a Girl),” “Offend in Every Way,” and “The Hardest Button to Button,” but strongly favours delayed backbeats in the studio and live versions of both “Seven Nation Army” and “Blue Orchid.” The band’s performance of “Dead Leaves and the Dirty Ground” on Saturday Night Live is characterized by both early and late backbeats.

Figure 24: Deviation of beat 3 from expectation as a percentage of mean IOI in the 2003 recording of the White Stripes’ “You’re Pretty Good Looking (For a Girl),” live at the TIM Festival. The highlighted area corresponds to the audio excerpt.

Media 5: Isolated kick and snare drum from the White Stripes’ “You’re Pretty Good Looking (For a Girl)” (live; 0:43–1:01), with early beat three attacks. Listen to Media 5.

White’s drumming also shows a great deal of variability around the mean in the placement of attacks. She has a larger Average Beat Coefficient of Variation (3.39) than all of the studied drummers other than Mitchell. This indicates inconsistency of attack placement. Consistency of attack placement can be thought of as a sign of professionalism that the White Stripes intentionally sought to avoid. As seen in Figure 23, live versions of “You’re Pretty Good Looking (For a Girl),” “Dead Leaves and the Dirty Ground” and “Seven Nation Army” have the highest ABCV values among the White Stripes songs we analyzed. The only White Stripes recording that we examined where the ABCV values are relatively low is the studio “Seven Nation Army,” perhaps not coincidentally the band’s most commercially successful release. This is a track that also features a relatively low tempo CV for the band, 1.22.

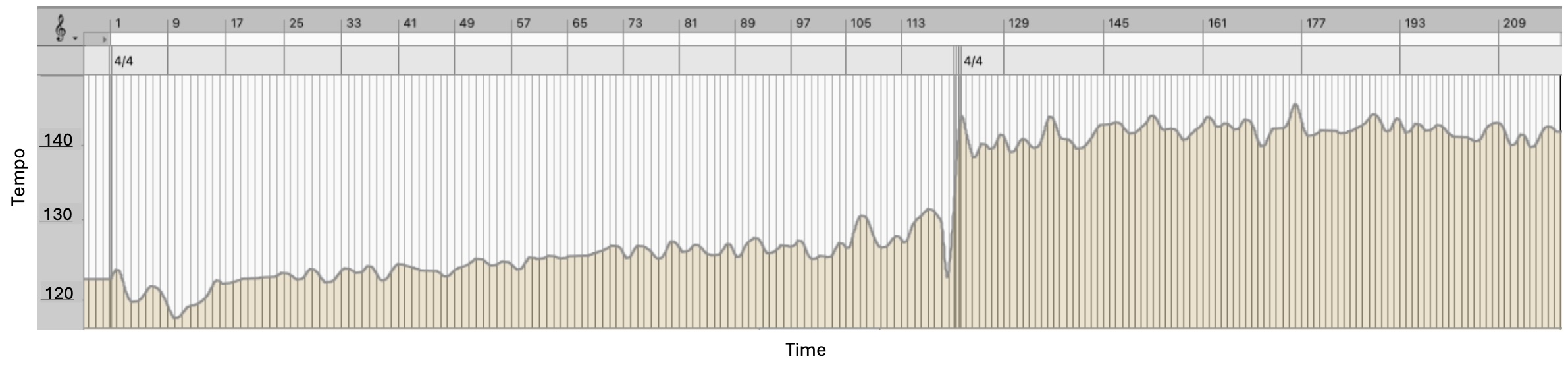

The median tempo CV for Meg White songs we analyzed—1.60— is the second highest among the five drummers studied, behind only Mitch Mitchell (Figure 8). The variability in some recordings is large enough to be clearly intentional. White Stripes live recordings, such as “You’re Pretty Good Looking (For a Girl)” (TIM Festival 2003, 4.92) and “Dead Leaves and the Dirty Ground” (Saturday Night Live 2002, 3.22), have particularly high tempo CVs. The TIM Festival version of “You’re Pretty Good Looking” (Figure 25) ranges from 124 BPM at the first entrance of the drum kit up to a high point of 145 BPM. The second verse is significantly faster than the first and the bridge boosts the tempo nearly 15 BPM, with a drop back down upon the return to a verse. The tempo variability thus correlates to a large extent with the formal structure, with the form further reinforced by the prominent cadential ritardandi at the ends of sections. The tempo shift at the start of the bridge is large enough to suggest musical intent and occurs in a less exaggerated form in the studio version of the recording. In other White Stripes songs, the tempo variability is more subtle and perhaps unintentional, but the band seemingly cultivated flexibility of tempo as part of its garage rock aesthetic.

Figure 25: Tempo map of the White Stripes’ “You’re Pretty Good Looking (For a Girl),” live at the TIM Festival 2003. Not shown is the pulseless guitar introduction before the drums first enter at 0:13.

Conclusion

Examination of microtiming and tempo variability in these five contrasting drummers provides some sense of the signature characteristics of each and of the extent to which commentary about them matches reality. Our measurement of quarter-note timing and tempo variability is necessarily a limited lens: these performers’ drumming could be examined in many other ways, whether through additional statistical analysis, close observation of taped performances, transcriptions, or further compiling existing commentary. In addition, drummer tendencies may change over the course of an individual’s career and undoubtedly depend to some extent on the characteristics of the particular song being played. But our findings reverberate beyond the specifics of quarter-note attack placement and tempo coefficient of variation, towards broader insights into these drummers and historical trends.

Our findings to an extent reflect larger changes in rock music over time. The oldest two drummers in the study, Ringo Starr and Mitch Mitchell, shared a proclivity for delayed backbeats, particularly beat 2, and a relatively small 4 to 1 IOI, as well as greater tempo variability. But the two also differed in important ways, with Mitchell playing more fills, having a much larger standard deviation for quarter-note attacks, and showing greater tempo variability than Starr, perhaps reflecting the influence of jazz on his playing. In addition, while songs with Mitchell tended to speed up, Beatles songs with Starr showed a significant tendency to end more slowly than they began.

Stewart Copeland and Phil Rudd, in the next generation, were most active in the late 1970s and early 1980s—an era when precise timing and tempo invariability were becoming a part of the popular mainstream. Copeland and Rudd, much steadier and with more precise attack placement than Starr and Mitchell, embodied the broader tension between the influx of technology into popular music in this period and the desire to remain “authentic” to a rock tradition connected with live performance, hard-earned skill, and youthful energy (Sheinbaum 2008, pp. 40–41). While Copeland often played to a click track or sequencer, sometimes even in live performance, Rudd displayed very precise timing and tempo precision without using a click. Of the five drummers in the study, Copeland showed the greatest tendency towards early backbeats. Meg White, the youngest of the five drummers studied, was born in 1974 and thus grew up in a world in which the popular mainstream was already dominated by drum machines, click tracks, and sequencers. Her rambunctious approach, marked by volatile timing and tempo, aligns with the band’s concept of swimming “against the tide of modern pop” (Perry 2009)—a stance also manifested in their cultivation of a live-music aesthetic and preference for analog production techniques.

Understanding individual drummers as well as larger historical trends will ultimately demand an approach that considers both the evidence detectable with contemporary technology and the larger historical context. Our use of recent technology to study the drumming of these five performers can serve as a model that, going forward, can be applied both to individual drummers as well as to larger collections of musical data.

The authors would like to thank their assistants Jonas Kastenhuber, Mira Perusich, and Thomas Zaterka.

Bibliography

Ainsworth, Patrick (2024), “Microtiming in Funk and Its Associated Styles. Towards a Typology of Micro-Rhythm in Groove-Based Music,” Ph.D. diss., Solent University.

Altham, Keith (2009), “Mitch Mitchell, 1947–2008,” Uncut, January, https://www-rocksbackpages-com.lmu.idm.oclc.org/Library/Article/mitch-mitchell-1947-2008, accessed 22 January 2025.

Aronoff, Kenny (1987), “Ringo Starr. The Early Period,” Modern Drummer, October, pp. 102–103.

Aukofer, Michael (2011), “Behind the Drumset with Stewart Copeland. Identifying the Value of Transcription and Modeling in the Study of a Rock Drumset Icon,” D.M.A. diss., University of Kentucky.

Bailes, Freya, Roger T. Dean, and Marcus T. Pearce (2013), “Music Cognition as Mental Time Travel,” Scientific Reports, vol. 3, 2690.

Baur, Steven (2012), “Backbeat,” Grove Music Online, Oxford, Oxford University Press, https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.A2227622, accessed 10 April 2025.

——— (2021), “Towards a Cultural History of the Backbeat,” in Matt Brennan, Joseph Michael Pignato, and Daniel Akira Stadnicki (eds.), The Cambridge Companion to the Drum Kit, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, pp. 34–51.

Brennan, Matt (2020), Kick It. A Social History of the Drum Kit, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Brower, Candace (1993), “Memory and the Perception of Rhythm,” Music Theory Spectrum, vol. 15, no 1, pp. 19–35.

Butterfield, Matthew W. (2006), “The Power of Anacrusis. Engendered Feeling in Groove-Based Musics,” Music Theory Online, vol. 12, no 4, https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.06.12.4/mto.06.12.4.butterfield.html, accessed 22 January 2025.

——— (2007), “Response to Fernando Benadon,” Music Theory Online, vol. 13, no 3, https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.07.13.3/mto.07.13.3.butterfield.html, accessed 22 January 2025.

Carter, David S., and Ralf von Appen (2025a), “Measuring the Myth. Microtiming and Tempo Variability in the Music of the Rolling Stones,” Theory and Practice, vol. 49–50, pp. 91–158, https://tnp.mtsnys.org/vol49-50/carter_von_appen, accessed 29 November 2025.

——— (2025b), “Tempo Variability in Billboard Hot 100 Songs, 1966–1995. Patterns, Click Tracks, and Historical Change,” Intégral, vol. 38, pp. 61–91, https://theory.esm.rochester.edu/integral/38-2025/carter-von-appen/, accessed 29 November 2025.

Cheston, Huw, Joshua L. Schlichting, and Ian Cross (2024a), “Jazz Trio Database. Automated Annotation of Jazz Piano Trio Recordings Processed Using Audio Source Separation,” Transactions of the International Society for Music Information Retrieval, vol. 7, pp. 144–158.

Cheston, Huw, Joshua L. Schlichting, Ian Cross, and Peter M.C. Harrison (2024b), “Rhythmic Qualities of Jazz Improvisation Predict Performer Identity and Style in Source-Separated Audio Recordings,” Royal Society Open Science, vol. 11, 240920.

Copeland, Stewart (2009), Strange Things Happen. A Life with the Police, Polo, and Pygmies, New York, HarperCollins Publishers.

Danielsen, Anne, Kristian Nymoen, Evan Anderson, Guilherme Schmidt Câmara, et al. (2019), “Where Is the Beat in That Note? Effects of Attack, Duration and Frequency on the Perceived Timing of Musical and Quasi-Musical Sounds,” Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, vol. 45, pp. 402–418.

Djupvik, Marita B. (2017), “Naturalizing Male Authority and the Power of the Producer,” Popular Music and Society, vol. 40, no 2, pp. 181–200.

Eells, Josh (2012), “Jack Outside the Box,” New York Times Magazine, April 8, https://www.proquest.com/magazines/jack-outside-box/docview/993882196/se-2, accessed 22 January 2025.

Flans, Robin (2004), “Classic Tracks. ‘Every Breath You Take’. The Police,” Mix Magazine, March, https://www.soundonsound.com/techniques/classic-tracks-police-every-breath-you-take, accessed 1 May 2025.

Frane, Andrew V. (2017), “Swing Rhythm in Classic Drum Breaks from Hip-Hop’s Breakbeat Canon,” Music Perception, vol. 34, no 3, pp. 291–302.

Freeman, Peter, and Lachman Lacey (2002), “Swing and Groove: Contextual Rhythmic Nuance in Live Performance,” in Catherine J. Stevens, Denis K. Burnham, Gary McPherson, Emery Schubert, and James Renwick (eds.), Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Music Perception and Cognition, Sydney, Adelaide, Causal, pp. 548–550.

Friberg, Anders, and Johan Sundberg (1995), “Time Discrimination in a Monotonic, Isochronous Sequence,” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, vol. 98, no 5, pp. 2524–2531.

Griffith, Mark (2009), “The Jimi Hendrix Experience’s Mitch Mitchell,” Modern Drummer, vol. 33, no 4, pp. 34–40.

Huron, David (2006), Sweet Anticipation. Music and the Psychology of Expectation, Cambridge, MIT Press.

Kaufmann, “Pistol” Pete (2010), “Reasons to Love Phil Rudd,” Modern Drummer, vol. 34, no 5, pp. 78-80.

London, Justin ([2004]2012), Hearing in Time. Psychological Aspects of Musical Meter, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Mack, Kimberly (2015), “‘There’s No Home for You Here’. Jack White and the Unsolvable Problem of Blues Authenticity,” Popular Music and Society, vol. 38, no 2, pp. 176–193.

Madison, Guy, and Björn Merker (2002), “On the Limits of Anisochrony in Pulse Attribution,” Psychological Research, vol. 66, pp. 201–207.

——— (2004), “Human Sensorimotor Tracking of Continuous Subliminal Deviations from Isochrony,” Neuroscience Letters, vol. 370, no 1, pp. 69–73.

Mattingly, Rick (1998), The Drummer’s Time. Conversations with the Great Drummers of Jazz, Cedar Grove, New Jersey, Modern Drummer Publications.

Micallef, Ken (2018), “Stewart Copeland: Stay Curious!,” Modern Drummer, vol. 42, no 6, pp. 26–32, 34, 37, https://www.proquest.com/, accessed 22 January 2025.

Micallef, Ken, and Donnie Marshall (2007), Classic Rock Drummers, New York, Backbeat Books.

Moore, Allan F. (1993), Rock. The Primary Text, Aldershot, Ashgate.

Okano, Masahiro, Masahiro Shinya, and Kazutoshi Kudo (2017), “Paired Synchronous Rhythmic Finger Tapping Without an External Timing Cue Shows Greater Speed Increases Relative to Those for Solo Tapping,” Scientific Reports, vol. 7, 43987.

Perry, Andrew (2009), “Jack White. Rock’n’Roll Star of the Decade,” The Guardian, 28 November, https://www.theguardian.com/music/2009/nov/29/jack-white-noughties-review, accessed 28 April 2025.

Peterson, Sean Michael (2018), “Something Real. Rap, Resistance, and the Music of the Soulquarians,” Ph.D. diss., University of Oregon.

Sheinbaum, John J. (2008), “Periods in Progressive Rock and the Problem of Authenticity,” Current Musicology, no 85, pp. 29–51.

Starr, Michael (2015), Ringo. With a Little Help, Milwaukee, Backbeat Books, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/lmu/detail.action?docID=5674469, accessed 22 January 2025.

Stubbs, David (2008), “Mitch Mitchell Remembered,” The Guardian, 13 November, https://www.theguardian.com/music/musicblog/2008/nov/13/mitch-mitchell-remembered, accessed 22 January 2025.

Thomson, Michael, Kennedy Murphy, and Ryan Lukeman (2018), “Groups Clapping in Unison Undergo Size-Dependent Error-Induced Frequency Increase,” Scientific Reports, vol. 8, no 1, p. 808.

Toews, Brandon (2023), “Meg White: 3 Reasons Why She’s a Drumming Genius,” Drumeo, https://www.drumeo.com/, accessed 22 January 2025.

Troes, Tessy (2017), “Measuring Groove. A Computational Analysis of Timing and Dynamics in Drum Recordings,” Master’s thesis, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, https://zenodo.org/record/.pdf, accessed 22 January 2025.

Wahlström, Kristian (2022), “Student-Centered Musical Expertise in Popular Music Pedagogy and Hard Rock Groove. A Design-Based and Psychodynamic Approach,” Ph.D. diss., University of Helsinki.

Wolf, Thomas, and Günther Knoblich (2022), “Joint Rushing Alters Internal Timekeeping in Non-Musicians and Musicians,” Scientific Reports, vol. 12, 1190.

Discography for live recordings (YouTube links provided for those without an official release)

AC/DC (1977), “Hell Ain’t a Bad Place to Be,” Bonfire (Live from the Atlantic Studios).

AC/DC (1977), “Live Wire,” Bonfire (Live from the Atlantic Studios).

AC/DC (1996), “Rock and Roll Ain’t Noise Pollution,” Plaza de Toros de Las Ventas, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=THDZMWtubVc.

AC/DC (1996), “Go Down,” VH1 Studios, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ULbteMojnx4.

AC/DC (1996), “Gone Shootin’,” VH1 Studios, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=85Nsyib4bv.

AC/DC (2009), “Shot Down in Flames,” Live at River Plate.

The Beatles (1964), “She Loves You,” Live at the Hollywood Bowl.

The Beatles (1964), “Rock and Roll Music,” Live at the BBC.

The Beatles (1964), “You Can’t Do That,” Live at the Hollywood Bowl.

The Beatles (1964), “Things We Said Today,” Live at the BBC.

The Beatles (1965), “Dizzy Miss Lizzy,” Live at the BBC.

The Beatles (1965), “Baby’s in Black,” Live at the Hollywood Bowl.

The Jimi Hendrix Experience (1967), “Purple Haze,” BBC Sessions.

The Jimi Hendrix Experience (1967), “Foxey Lady,” BBC Sessions.

The Jimi Hendrix Experience (1967), “Little Miss Lover,” BBC Sessions.

The Jimi Hendrix Experience (1967), “The Wind Cries Mary,” The Jimi Hendrix Experience (Deluxe Reissue) (Live Olympia Theater, Paris).

The Jimi Hendrix Experience (1968), “Little Wing,” Hendrix in the West.

The Jimi Hendrix Experience (1968), “Red House,” Hendrix in the West.

The Police (1979), “Can’t Stop Losing You/Reggatta de Blanc,” Countdown, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sM0tfIgwR6w.

The Police (1979), “Born in the 50’s,” Musikladen, https://www.youtube.comwatch?v=sOdvSClxZy.

The Police (1980), “When the World Is Running Down, You Make the Best of What’s Still Around,” Rockpalast, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-V7qgM2X3xg.

The Police (1981), “Too Much Information/When the World is Running Down, You Make the Best of What’s Still Around,” Sporthalle Böblingen, Oct. 1981, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=prmGunQH9iU&list=RDprmGunQH9iU&start_radio=1 (34:12).

The Police (1983), “Spirits in a Material World,” Synchronicity (Super Deluxe Edition) (Live at the Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum).

The Police (1983), “King of Pain,” Synchronicity: (Super Deluxe Edition) (Live at the Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum).

The Police (2008), “Every Breath You Take,” Tokyo Dome, https://www.facebook.com/.

The White Stripes (2001), “Offend in Every Way,” White Blood Cells (Deluxe) (Live at the Gold Dollar, June 7).

The White Stripes (2002), “Dead Leaves and the Dirty Ground,” Saturday Night Live, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ziuu93gFaGg.

The White Stripes (2003), “You’re Pretty Good Looking (For a Girl),” TIM Festival, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KpUiBxleaHc.

The White Stripes (2003), “Seven Nation Army,” Conan, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h35VbsZbUZU.

The White Stripes (2004), “Ball and Biscuit,” Under Blackpool Lights (DVD), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P0F8FrM4Vds.

The White Stripes (2007), “Blue Orchid,” Rock am Ring, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2cvhP-7yv_E.

| RMO_vol.12.2_Carter and von Appen |

Attention : le logiciel Aperçu (preview) ne permet pas la lecture des fichiers sonores intégrés dans les fichiers pdf.

Citation

- Référence papier (pdf)

David S. Carter and Ralf von Appen, « Finding a Fingerprint. Microtiming and Tempo Variability in Five Renowned Rock Drummers », Revue musicale OICRM, vol. 12, no 2, 2025, p. 80-106.

- Référence électronique

David S. Carter and Ralf von Appen, « Finding a Fingerprint. Microtiming and Tempo Variability in Five Renowned Rock Drummers », Revue musicale OICRM, vol. 12, no 2, 2025, mis en ligne le 13 mai 2025, https://revuemusicaleoicrm.org/rmo-vol12-n2/microtiming-tempo-variability-rock-drummers/, consulté le…

Auteurs

David S. Carter, Loyola Marymount University

David S. Carter is an Assistant Professor of Music at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles, where he teaches music theory and popular music. He has published in Music Theory Online and has presented papers at the Society for Music Theory annual meeting and the IASPM international and U.S. conferences. As a composer, he won the Iron Composer competition at Baldwin Wallace University and Northwestern University’s William T. Faricy Award. He earned his doctorate in music composition at Northwestern, his J.D. at the University of Southern California, and his B.A. at Yale University.

Ralf von Appen

After graduate studies in musicology, philosophy and psychology, von Appen worked as a teaching and research assistant at universities in Bremen and Giessen, where he received a doctorate in musicology in 2007. In 2019 he became Professor for the Theory and History of Popular Music at the University for Music and Performing Arts Vienna. He has published widely about the history, psychology, aesthetics, and analysis of popular music and presented papers at conferences all across Europe and the U.S. Ralf von Appen was chairman of the German Society for Popular Music Studies (GfPM) from 2008 to 2020.

Notes

| ↵1 | This study had moderate success with distinguishing pianists solely on the basis of their rhythmic characteristics, with the pianists’ mean lag behind the drummer’s beat being the most reliable means of distinction (2024b, p. 11). |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | The BBC “live” recordings by the Beatles and the Jimi Hendrix Experience included in the study (three from each artist) were, despite the labeling of the Beatles release, prerecorded in a radio station studio without a live audience. |

| ↵3 | See https://www.sonicvisualiser.org/ and https://www.vamp-plugins.org/download.html. Within the plugin, we used a Hann window shape, an FFT window size of 128 samples, and a window increment of 32. We started with a Threshold setting of three and then increased or decreased it to automatically mark the quarter notes. In cases where the algorithm did not detect an attack that actually occurred, we lowered the Threshold in a second layer and copied the resulting markers into the first layer. Baume (2013) discusses how the plugin works. Cheston et al. 2024a instead used a neural-network-based tool, CNNOnsetDetector within the Python library madmom, for detecting piano note onsets (pp. 6–7). But automated identification of drum attacks is a relatively straightforward process compared to identifying attacks of bowed or blown instruments, and the BBC Rhythm: Onsets plug-in marked attacks in a consistent manner that corresponded with our perception as listeners. |

| ↵4 | The backbeat pattern, in which the bass drum plays on the first and third beats and the snare drum on the second and fourth beats of a 4/4 measure, is by far the most widespread accompaniment pattern across many styles of popular music. Allan Moore has called it the “standard rock beat” (1993, p. 38; see also Baur 2012; Brennan 2020, pp. 179–190). Playing eighth notes on hi-hats is a crucial component of rock drumming, but current technology often does not successfully separate out hi-hats, particularly in recordings released prior to 1980. |

| ↵5 | References to “the listener” in this essay refer to an imagined average listener—not necessarily a music scholar or a trained listener. Individual listeners’ experiences can differ in important ways. But the difference between the perceptions of trained and untrained listeners in many cases is not large (London 2012, pp. 172–173), and the conjectured experience of an average listener can provide an important reference point for musical analysis. |

| ↵6 | Researchers have differing views regarding how much time a listener considers when perceiving tempo (Bailes et al. 2013, p. 1). Frane (2017, p. 296), Freeman and Lacey (2002, p. 549), and Troes (2017, p. 35) use the current bar as the basis for measuring microtiming deviations. This approach, when applied to beats 2, 3, or 4, counter-intuitively compares attacks to attacks the listener has not yet heard. Butterfield (2006, pp. 50–51) and Frane (2017, p. 296) use the previous bar and previous beat, respectively, as secondary measurements for ascertaining the extent of deviations from the beat. |

| ↵7 | This assumes that listeners have an expectation of isochrony (or at least near-isochrony) on some level, allowing them to entrain to a stream of pulses (Brower 1993, pp. 26–27). A listener who has heard a repeating pattern of microtiming deviation may develop an expectation that that pattern will continue, but even if that expectation is fulfilled it is on some level still a deviation from an isochronous expectation. |

| ↵8 | Using the previous/accumulated method, the microtiming deviation of downbeats was measured by comparing the length of the just-completed bar with that of the bar before that. This is consistent with our approach to the other three beats in the bar; with a downbeat, the “accumulated” time is necessarily an entire bar. |

| ↵9 | Recordings referenced in this article are studio recordings unless specifically labeled as live versions. |

| ↵10 | While measurements of microtiming deviations calculated with reference to the previous bar perhaps better reflect the listener’s experience in real time, they are more sensitive to tempo fluctuations than measurements made using the current bar as the tempo reference. This is simply because a longer time period (including both the previous and current bars) is encompassed within the comparison. Additionally, our choice of the previous/accumulated method does not mean that the other three approaches lack validity in all instances or for all listeners. For instance, listeners will hear beat 3 and beat 4 attacks in part in relation to downbeats, but they also (even simultaneously) can hear the interonset intervals between 2 and 3 and between 3 and 4. They may therefore also have a perception of earliness or lateness from that perspective. |

| ↵11 | This measurement is calculated based on means for each beat for the song as a whole. Individual instances of a beat lacking an attack do not interfere with the averaging of all instances of the beat that have an attack. |

| ↵12 | The ABCV does not rely on either previous-bar or current-bar projections of expected beat placement. It measures the amount of variability with each of the four IOI possibilities in a given song. |

| ↵13 | Thus, if a song began with a section without a backbeat variant, the “starting” tempo would be from the start of the portion with the backbeat. |

| ↵14 | These ranges derive from our evaluation of the tempo variability of 423 popular songs in Carter and von Appen 2025b, where we compared tempo CV values with published interviews and other sources documenting whether a click track, sequencer, or drum machine was used on a given recording (pp. 75–77). Our evaluation in this previous study, however, was based on tempo maps of original full recordings created with the software Melodyne, while in the present study CV calculations were instead made using the Moises-derived drum stems, and portions without a backbeat variant were excluded. Therefore, the ranges cited in Figure 5 should be viewed as approximations when compared with the CV calculations in the present study. |

| ↵15 | The mean IOI from beat 2 to 3 is three milliseconds below average, and there are several beat 3 attacks in the song that are substantially earlier than that. Additionally, the mean IOI from 3 to 4 is three milliseconds above average. So listeners may nevertheless hear numerous third beats as “early.” |

| ↵16 | Tempo CV values for the five drummers in the study are just for the analyzed portions of the songs, using the isolated drums. “Billboard Top 15” is the year-end top 15 for every other year between 1966 and 1994, with the addition of 1979 and 1995 (see Carter and von Appen 2025b). These values were calculated based on the full recordings. |

| ↵17 | In a studio setting, a band could do many takes and edit together portions of multiple takes in order to achieve greater steadiness on the released recording. |

| ↵18 | We use medians rather than means for groups of CV values because, given the relatively small number of recordings, a single outlier can have a large effect on a mean value. Tempo CV values themselves are highly sensitive to variability and can be significantly influenced by a single outlier bar in a song. |

| ↵19 | Celemony’s Melodyne 5 Studio is an audio editing application that, among other features, detects attack transients in order to generate tempo maps. In cases where the automatically generated maps do not exactly match the audio, the user can easily make manual adjustments to correct tracking errors. |

| ↵20 | The song was titled “Foxy Lady” on the original U.K. release of the album Are You Experienced, then retitled “Foxey Lady” for the U.S. album and single. |

| ↵21 | We use mean delay rather than median when analyzing attack placement because extreme values have a real effect on the listener. In our listening experience, even a relatively small number of very late attacks combined with others near average can give a sense of delay. |

| ↵22 | Jazz influence in drumming is often associated with taking more liberties, variation, and flexibility. See, e.g., Mattingly 1998, p. 13. |

| ↵23 | The “Reggatta de Blanc” portion of the medley does not use a backbeat pattern or variant. |