Trance and Dance in Bali (1951).

On the Musical Selections of Mead and Bateson’s Film

I Putu Arya Deva Suryanegara

| PDF | CITATION | AUTEUR |

Abstract

This article discusses the soundtrack used for the ethnographic film Trance and Dance in Bali made by anthropologists Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson in 1951. The soundtrack consists of a selection of Balinese gamelan and voice pieces, recorded by the labels Odeon and Beka in 1928, and chosen and arranged by Colin McPhee to fit the on-screen action. The film depicts a reenactment of a calonarang ceremony, a ritual which takes place in villages in Bali during the night, consisting in a sacred dance-drama that is highly regionally specific in its execution. However, for the purposes of Mead and Bateson, this calonarang was performed outside its ritual context in order to provide footage for the ethnographers. The aim of this article is to determine the original source of the soundtrack, discuss what is presented visually in the film, assess the adequacy (or inadequacy) of the choices of music in relation to the image, and in the case of inadequacy, to provide suggestions for musical alternatives. The musical and ritual regionalisms inherent to Balinese musical and ritual practice render some of the soundtrack choices inadequate. We argue that the chosen pieces do not all appropriately support the calonarang performance and ceremony depicted, due to inaccurate musical and ritual regionalisms.

Keywords: Bali 1928; Balinese gamelan; calonarang; Colin McPhee; Odeon and Beka.

Résumé

Cet article traite de la trame sonore utilisée pour le film ethnographique Trance and Dance in Bali produit par les anthropologues Margaret Mead et Gregory Bateson en 1951. La bande originale résulte d’une sélection de trames de gamelan et de chants balinais issues des enregistrements réalisés par les labels Odeon et Beka en 1928, choisies et arrangées par Colin McPhee pour soutenir l’action visuelle. Le film montre la reconstitution d’une cérémonie calonarang, un rituel prenant place la nuit dans les villages à Bali et consistant en une danse dramatique dont la spécificité d’exécution est hautement régionale. Toutefois, pour les besoins de Mead et Bateson, ce calonarang fut interprété hors de son contexte rituel afin de fournir des séquences filmiques aux ethnographes. L’objectif de la présente recherche consiste à déterminer la source originale de la bande sonore, discuter de ce qui est présenté visuellement dans le film, évaluer l’adéquation (ou l’inadéquation) du choix de la bande sonore par rapport aux images, et dans le cas d’une inadéquation, fournir des suggestions musicales alternatives. Les régionalismes musicaux et rituels inhérents aux pratiques balinaises rendent certains des choix musicaux de la trame sonore inadéquats. Nous soutenons que les pièces sélectionnées ne supportent pas toutes de façon appropriée la performance et la cérémonie.

Mots clés : Bali 1928 ; calonarang ; gamelan balinais ; Colin McPhee ; Odeon et Beka.

The film Trance and Dance in Bali1The film can be watched here: https://www.loc.gov/item/mbrs02425201/ (accessed April 11, 2022). was made as a collaboration between American and English anthropologists Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson during two separate visits to Bali, in 1937 and 1939. This film, released in 1951, is one of only eight ethnographic films selected by the us National Film Preservation Board for preservation in the Library of Congress (Durington and Ruby 2011, p. 205). While the ethnographic status of some of these films has been discussed by some critics, Bateson and Mead’s films have not received much commentary and analysis in anthropological literature (Henley 2013, p. 75). Specifically, very little commentary can be found discussing the musical aspects of Trance and Dance in Bali, even though music plays an important role in this film.2I come to this research situated as a Balinese researcher, composer, and musician who has studied the musical practices of my home village in Kerobokan, Bali since I was a child. I do not want to overstate my expertise in relation to the subject matter—anyone claiming to have a final authoritative opinion regarding musical practices from any given region of Bali, let alone practices that took place roughly 100 years ago, would be misrepresenting what can be known. Musical and ritual practices in Bali are extremely varied and context dependent, and as living practices, they develop over time and change as they are passed from generation to generation. However, there are common threads … Continue reading

Mead and Bateson met in New Guinea in 1933 during their research on “characterizing cultures by temperament and gender” (Jacknis 1988, p. 160). After Mead returned to New York, she became interested in Balinese culture through films produced by her former student, Jane Belo, fellow researcher and spouse of Colin McPhee, while Belo was professor at Columbia University (ibid., p. 163). Belo’s research focused on the trance phenomena in Balinese religious practice, whereas McPhee’s primary area of research was gamelan.3Gamelan is a traditional musical ensemble from the islands of Bali and Java. In this paper, the word “gamelan” always refers to the Balinese gamelan. They both did field research in Bali, in what is present-day Indonesia, for extended periods of time during the 1930s. From their newly aroused interest, Mead and Bateson began research in Bali shortly after getting married. The filming of Trance and Dance in Bali was supported by the Committee for the Study of Dementia Praecox, and funded by the American Museum of Natural History, Cambridge University, the Social Science Research Council (SSRC) (ibid., p. 161).

Trance and Dance in Bali was recorded in two separate research excursions to Bali, on December 16, 1937 and February 8, 1939 in Pagutan4Pagoetan village, which Mead and Bateson reference in the film, is a banjar (localized community organizations in Balinese society). Pagutan is in Batubulan village today. village (ibid., p. 171). Mead and Bateson recorded most of the film footage during the first performance, but recorded the second performance to provide supplementary footage (Henley 2013, p. 96; Jacknis 1988, p. 162). Following Mead and Bateson’s suggestion, the second performance was arranged to showcase female patih5Patih refers to the people who attack Rangda using a keris (ceremonial knife), regardless of gender. In this story, patih are on the side of Pandung and Barong. instead of the usual male patih (Bateson and Mead 1942, p. 167).

Trance and Dance in Bali is part of a larger series of films by Mead and Bateson released the same year called Character Formation in Different Cultures, which also included the films Bathing Babies in Three Cultures, Karba’s First Years, and First Days in the Life of a New Guinea Baby. During the following two years, they published two more films: A Balinese Family and Childhood Rivalry in Bali and New Guinea (Jacknis 1988, p. 170). Those six films were shot by Bateson and Belo, with Mead as the editor, scriptwriter, and narrator, and Josef Bohmer as film editor (ibid.).

For Trance and Dance in Bali, the footage stages a calonarang, also known as dramatari calonarang.6See pages 96-97 for the definition of dramatari calonarang. The filmed performance was specifically staged for the researchers, rather than being a typical calonarang that happens periodically in Balinese villages. A sacred dramatari calonarang occurs during the night, to provide a mystical atmosphere of the performance, and some parts of the performance may sometimes even take place in a cemetery. However, the researchers arranged the calonarang staged during the day, in order to support the quality of light necessary in order to film (ibid., p. 167). Significantly, the soundtrack for this film does not consist of original sound recordings corresponding to the footage on screen. Although it was technically possible to record the live sound of the events, as some previous anthropologist filmmakers had done, the cost, technical difficulty, and low quality of recording in the field on phonograph wax cylinders was deemed prohibitive (Henley 2013, p. 86).

The introductory captions of Trance and Dance in Bali claim that Colin McPhee “arranged” the music, while he in fact simply selected works from albums released in 1929 by two German labels, Odeon and Beka.7The music may not have been added to the film until 1950, when Mead began to work with Josef Bohmer to edit the footage originally taken in 1937 and 1939 (Jacknis 1988, p. 70). Some of these Odeon and Beka albums that McPhee chose for this film were re-released by the label Decca in the United States in 1951 (Clendinning 2017, p. 167). The list of the McPhee collection from 1930 to 1964 shows that he had 31 albums from Odeon, Beka, and Decca, each album containing two 78s (McPhee 2009, pp. 178‑182). Thus, McPhee likely had (at least) 62 recordings of Balinese gamelan and voices from these sources, and it is possible he chose some of them for the soundtrack of Trance and Dance in Bali.

McPhee’s years of study in the late 1930s with the famous composer I Wayan Lotring (whose compositions are still widely played today) added to his already extensive research about Balinese gamelan (Sudirana 2019, p. 42). Although Colin McPhee might have been one of the most knowledgeable foreigners about gamelan at the time of the soundtrack editing, the relationship between the music, the scenes, and the function of the music is not always well matched. It is possible that McPhee may not have been clearly informed about the source or the original context of these recordings at that time, or perhaps he did not have access to recordings which fit exactly with the context on screen.8The Odeon, Beka, and Decca albums which McPhee possessed merely note the title of pieces and the name of artists or groups involved. One can assume the research at the time was less rich than later provided by Herbst. Regardless of the reason, it is clear that some of the soundtrack in Trance and Dance in Bali is neither representative of a calonarang performance nor of the ceremonies that take place after the end of the calonarang.9See pages 96-97 about calonarang.

In this paper, I am going to establish the original source of the soundtrack used for Trance and Dance in Bali, discuss what is presented visually in the film, assess the adequacy (or inadequacy) of the choice of soundtrack in relation to the images seen on screen, and in the cases where the soundtrack and on-screen action are mismatched, provide suggestions for alternatives to the soundtrack.

The Film

Mead and Bateson’s film Trance and Dance in Bali depicts a calonarang ceremony performed in a secular setting. As mentioned above, the soundtrack was chosen and edited by McPhee, from albums originally released by labels Odeon and Beka in 1929 and later re-released by the label Decca in 1951.

The Images

Belo stated that the performance seen in Trance and Dance in Bali is called a calonarang (Belo 1961, p. 159).10There exist some inconsistencies in the naming conventions between what is found in Belo’s description, and what is seen today in the calonarang story. It is unclear whether, at the time of the recording, these names were used interchangeably or, as is seen today, they refer to slightly different instances. For example, the story takes place during the reign of King Prabu Siwasipoerna, rather than King Erlangga, as is seen today. The witch is also given a different name, Ni Doekoeh Batoer, whereas in calonarang today she is named Walu Nateng Dirah. A calonarang is an epic story taking place in the era of King Erlangga’s reign on the island of Java in the 9th century. This legend has evolved into many forms of sacred performing arts which are still practiced in many regions of present-day Indonesia (Wirawan 2019, p. 71). The calonarang or dramatari calonarang (literally means calonarang dance drama) in the film seems to be a secular dramatari calonarang that was not staged for a ceremony in that village. There are two types of calonarang that are practiced in Bali today, they are sacred calonarang and secular calonarang (Wirawan 2020, p. 2474). The sacred calonarang is used as a complement to some Hindu religious ceremonies in Bali, while the secular calonarang is mostly done specially for tourist entertainment (Wirawan 2019, p. 71). The sacred calonarang was adapted for tourism starting in the Dutch colonial era and more strongly during the 1930s, at which time many Balinese were creating performances targeted toward tourists at the advice of German painter Walter Spies (Putra, Arta et Purnawati 2017, p. 5).

The sacred dramatari calonarang induces trance states in its participants by channeling spirits through sacred objects, such as Barong and Rangda costumes. The costumes are first properly prepared for the kerauhan, a trance which results from spiritual ritual with an array of offerings. When worn by designated dancers, called penyungsung,11The penyungsung is a person chosen by the holy spirit inhabiting the costume, in this case Rangda or Barong. They offer their body for the kerauhan from the deities. Under their possession, the penyungsung will dance, participate in procession, and take part in the calonarang ceremony as an incarnation of a holy spirit. the costumes become manifestations of gods. These incarnations of deities are believed to bring positive energy to the village where the calonarang is performed. The narrative symbolically enacts the battle between positive and negative energies through the positive Barong and negative Rangda.

After the calonarang in Trance and Dance in Bali, the film shows a ceremony in the temple with people coming out from the kerauhan, which rarely happens in a secular calonarang today.12It seems that they were permitted to enter the main part of the temple, where some temples do not allow outsiders to enter the sacred part. It depends on the rule in each village. In sacred calonarang, people usually make an offering (ngaturang banten) before and after a performance. Before a calonarang, a pemangku (lay priest) will make offerings to gods in supplication for a smooth performance. Meanwhile, after the calonarang, there is a ceremony called ngeluar or nyineb where people place Rangda and Barong in the place that has been provided in the temple (Murdaningsih, Widiasih and Brahman 2017, p. 55). The ceremony shown on screen seems to be ngeluar, which takes place in the main part of the temple after the performance. Unfortunately, the film does not show the ceremony before the performance. Both ceremonies are usually expected for a sacred calonarang to be considered acceptable for religious performance, rather than merely as a show.

The Sound

McPhee chose and edited six gamelan pieces for building the soundtrack of Trance and Dance in Bali. As mentioned above, these pieces were likely taken from the original Odeon and Beka Balinese music albums released in 1929, and one of them may have been taken from a Decca album released in 1951. There is one recording that McPhee chose for the soundtrack of this film which is not available in the Finding Aid for the Colin McPhee Collection 1930-1964 in University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) archive.13McPhee might not have given this recording or album to the UCLA archive. All six pieces, along with all other original recordings available, were later digitized and archived as part of Edward Herbst’s research project Bali 1928, released in 2009 (Herbst 2009, p. 66). They can therefore be found today on the first four volumes of Herbst’s series.14The five Bali 1928 volumes can be found at https://bali1928.net/bali-1928-on-spotify/ or

https://edwardherbst.net/?page_id=61 (accessed April 11, 2022).

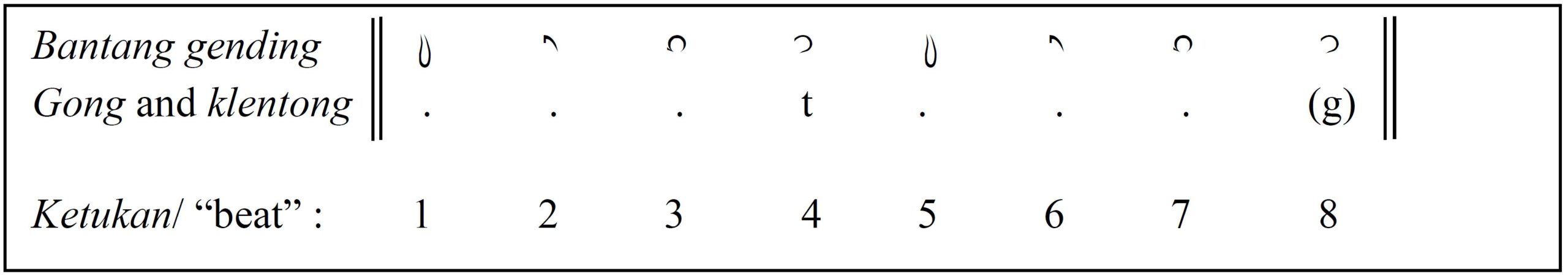

Below is a table of the gamelan pieces heard in the film in order of appearance, with the corresponding list of recordings from Finding Aid for the Colin McPhee Collection 1930–1964 of Odeon, Beka, and Decca recordings, and the volume and track number from the Bali 1928 series.

Figure 1: The soundtrack.15The time codes used throughout the text are based on the online version of the film: www.loc.gov/item/mbrs02425201/ (accessed April 11, 2022).

Figure 1: The soundtrack.15The time codes used throughout the text are based on the online version of the film: www.loc.gov/item/mbrs02425201/ (accessed April 11, 2022).

The German labels Odeon and Beka sent a team to Bali from 1928 until probably 1929 to manage the recording process where Walter Spies was their artistic advisor (Herbst 2014, p. 4; Kunst 1974, p 24). They published recordings of contemporary and earlier styles of Balinese gamelan and vocal music in 1929, both in Bali and internationally (ibid.). Unfortunately, during World War II, the factory of Carl Lindström A.G., the parent company of the labels, was bombed. The production of the albums was forever halted (ibid., p. 6). Eight of the Odeon and Beka recordings were re-released on the album Music of the Orient by the Austrian ethnomusicologist and pioneer of sound recording Erich M. von Hornbostel in 1934 by Parlophone, and re-released again by the label Decca in 1951 (Clendinning 2017, p. 167). The rest remained unavailable until recently (ibid.).

McPhee first heard some of those records in New York in 1930-31 (Herbst [n. d.]). The Balinese gamelan recordings, coupled with an existing interest in Indonesian arts, had such a significant impact on him that he went to Bali soon after (Belo 1970). In Bali, he bought at least two of those albums (McPhee 1946, p. 72). The exact sound material to which McPhee had access while editing Trance and Dance in Bali likely included at least the thirty-one 78s from Odeon, Beka, and Decca from his own collection. To put together the soundtrack, he seems to have used material from these Odeon, Beka, and Decca albums, undertaking minimal editing. Edward Herbst researched these recordings extensively, making it possible to associate the sound of the film to its sources.16Herbst found a total 111 78 rpm disks of Odeon and Beka. He began to publish his research from 2009 until 2015 including the Odeon and Beka album 65s. Herbst published the recordings in five volumes: Bali 1928, vol. 1: Gamelan Gong Kebyar Music from Belaluan, Pangkung, Busungbiu; Bali 1928, vol. 2: Tembang Kuna. Songs from an Earlier Time; Bali 1928, vol. 3: Lotring and the Sources of Gamelan Tradition; Bali 1928, vol. 4: Music for Temple Festivals and Death Rituals; Bali 1928, vol. 5: Vocal Music in Dance Dramas. Jangér, Arja, Topéng & Cepung.

Two artists and three groups were involved in the making of the pieces chosen for the soundtrack of Trance and Dance in Bali (see Figure 1): I Wayan Lotring and his gamelan Palegongan group of banjar Tegal, Kuta; gamelan Gong Kebyar of Busungbiu, Buleleng; singer and dancer Ni Lemon; and gamelan Angklung of Pemogan (Herbst 2009, pp. 50–56; 2014, pp. 79–80; 2015a, pp. 42–50; 2015b, pp. 83–84).

Soundtrack Choices: Adequacy and Suggestions

In any calonarang taking place in Bali, whether it be a religious ceremony or a secularized performance, specialized types of pieces are required at predetermined moments to accompany and facilitate the action taking place. In calonarang, the most typically used gamelan ensembles to accompany the drama are palegongan, bebarongan, and gong kebyar. These ensembles are used to support the same stories and characters, familiar across a wide variety of Balinese theatrical art forms—but depending on the context, these same characters may be referred to by different names. Thus, the same character under different names would still play the same tokoh17Concerning the term of tokoh in (Suartaya 2011). or role in the dance. Some examples of this might be seen by comparing the story of calonarang with a similar type of rite, called penyalonarangan (literally means “in the way of calonarang”18Translated by the author.). In both, there is the tokoh, or role of Matah Gede, the character of the witch. In the story of calonarang, the witch herself is named Walu Nateng Dirah, whereas in the story of penyalonarangan, she could go by one of four names depending on which part of the story is being dramatized: Balian Batur, Basur, Dayu Datu, or Ni Rimbit. Regardless of these naming differences, the musical composition is always tied to the tokoh of the character, and thus will always portray the same characteristics, whether it is in calonarang or penyalonarangan.

It is crucial to understand Balinese music through the lens of the Hindu religious context in which it is situated and from which it emerges. All the formal elements of the music, even down to the notes of the scale, have their origin in Balinese Hindu philosophy (see Figure 7 in annex). In many ways, this fact was substantially overlooked, or at least only partially understood, by McPhee when he chose the music for the film, perhaps being more concerned with musical rather than musical-philosophical considerations. One example of this is the concept of Panca Gita (“Panca” means five, “Gita” for song), which are the five sounds necessary for a Balinese Hindu ceremony to be complete. These sounds are gamelan, mantra, genta, kulkul, and kidung. In a calonarang ceremony, the concept of Panca Gita also applies, and it is clear that the sonic environment of the calonarang cannot be random or incidental, but must serve a highly curated and specific function in the completeness of the ceremonial or secular rite taking place. In McPhee’s choices for Mead and Bateson’s film, the only two elements of Panca Gita that can be heard are gamelan and kidung, creating a sonically and philosophically incomplete musical soundscape for the ritual context depicted.

The next section will provide detailed discussion of all six pieces in order of appearance in the film Trance and Dance in Bali. Each piece is presented in the following fashion: title, type of ensemble, and timecode where it can be heard in the film; next is a critical analysis, and finally, where appropriate, a suggested alternative soundtrack.

Gambangan, on gamelan palegongan,19Finding Aid for the Colin McPhee Collection 1930–1964 mentions the title of the piece and the group playing: Peloegon (gambangan) – Di Mainken Oleh: Pelegongan, Koeta on the 78 rpm Odeon: Jab 550, Jab 551 on side B. In the Herbst release, this piece is on the album Bali 1928, vol. 3: Lotring and Sources of Gamelan Tradition, track #7. from 00:28 to 02:24

Gambangan (Gegambangan) was composed by I Wayan Lotring in 1926 (Herbst 2015a, p. 48). It was inspired by the piece in gamelan gambang called Pelugon (ibid.). The word gambang refers to a gamelan ensemble consisting of four interlocking bamboo instruments and two or four gangsa (metallophones). As an ensemble, gambang is used for different ceremonial functions depending on the practices of each specific region of Bali. For instance, in Kerobokan village, gambang is used for Pitra Yadnya (cremation) and in eastern Bali it is mostly used for Dewa Yadnya (ceremonies for Gods in the temple). However, Lotring’s Gambangan does not hold a typical function of a gamelan gambang. It is often played as a tabuh petegak (an opening piece for a gamelan performance), but is not necessarily specific to any one type of ceremony. It seems appropriate that Gambangan was used as the introduction to Trance and Dance in Bali, given its function as an introductory piece. However, in modern practice, one would be unlikely to see a calonarang begin with Lotring’s Gambangan. The performance would be more likely to begin with a piece such as tabuh bebarongan20Tabuh bebarongan is a composition on gamelan palegongan and bebarongan using a medium kendang with a panggul or mallet. because this piece is used to evoke the Barong identity.

Gambangan used in the soundtrack of Trance and Dance in Bali was performed by Lotring’s group in banjar Tegal, Kuta, using the gamelan palegongan of Kuta. There is an opinion from “several listeners […] that the Kuta musicians of 1928 may not have had time to perfect and smooth out the kotekan21Kotekan is interlocking rhythmical patterns proper to Balinese gamelan. and uneven phrasings of this challenging new composition” (ibid.). But this unevenness could also be attributed to microphone placement.

Calonarang Sisia, on gamelan palegongan,22Finding Aid for the Colin McPhee Collection 1930–1964 mentions the title of the piece and the group played: Tjalon – Narang, Sisija – Di Mainken Oleh. Pelegongan, Koeta on the 78 rpm Decca: Jab 548, Jab 549 on side A. In Herbst release, this piece is on the album Bali 1928, vol. 3: Lotring and Sources of Gamelan Tradition, track #4. from 02:25 to 04:00

Calonarang Sisia is usually called Gending Sisya (literally “piece for sisia or sisya”). Considering the laras (tuning system) of the gamelan, it is possible that this piece could have also been played by the palegongan gamelan group of Kuta.

The scene clearly portrays a sisia23The sisia are female disciples of the witch Matah Gede, and in this opening dance they are seen in beautiful human form with their hair long and flowing (performed by young girls, age 11 or thereabouts, into the 1930s) (Herbst 2015a, p. 43). dance, and while it is undoubtedly related to the sisia dances seen in contemporary calonarang, it bears a few key differences. If one compares the dance costume seen in the film with those seen in contemporary Bali, it actually bears more resemblance to the costume of another type of dance called gambuh. In fact, the calonarang originally developed out of classical gambuh dance drama, beginning in the first decades of the 20th century, by combining elements of various Barong and Rangda rituals with gambuh (ibid., p. 42). So we can see that the condong (assistant) to the Matah Gede24Matah Gede is a tokoh who is very powerful and transforms into Rangda. of the calonarang is based on the maidservant to gambuh’s Putri ‘princess’, and the sisia are based on gambuh’s kakan-kakan (ibid., pp. 42–43). Therefore, we can see a clear through-line of development from gambuh to the contemporary version of the calonarang, and interestingly, we can see an earlier version of the calonarang costumes by watching the film. The dance costume of the sisia and condong in the film is not like the contemporary one, which has developed into a more complex costume.

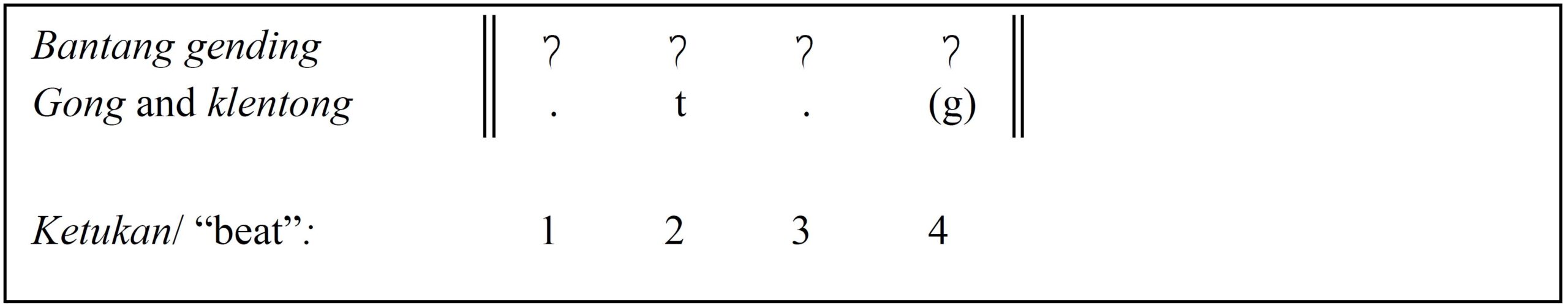

McPhee’s choice of Calonarang Sisia for the entrance of the sisia dancers at the beginning of calonarang is fitting. The note deng25Deng is the name of a note in Balinese gamelan. The five notes on Balinese gamelan are ding, dong, deng, dung, and dang. also plays an important structural role in the piece, where one hears a preponderance of the note deng throughout the bantang gending (structural melodic line), and critically, the note deng corresponds with the gong at the end of the cycle. In this sacred context, the note deng is associated with supernatural energies that have a sacred atmosphere.26I believe this concept is well known to Balinese gamelan scholars. If I remember correctly, the first time I heard it during a gamelan theory class was directed by I Gusti Ngurah Padang at SMKN 3 Sukawati. Therefore, there are many gamelan pieces where the note deng is used to accompany and facilitate religious ceremonies, as can be seen in the music played for kerauhan (trance) ceremony, in addition to calonarang pieces (Figure 2).

The dance movement seems to fit with the accent of gong and klentong instruments. The gong is played at the ketukan27In this context, ketukan is a “beat” in Balinese gamelan through a kajar instrument. eight, or the end of the eight-beats cycle, and the klentong is played at ketukan four. Therefore, each of these instruments is played every four beats (Figure 2).

The gong and klentong are very important structural accents for the dance movement.28See Michael Tenzer’s explanation of colotomic structure (Tenzer 2000, p. 7). Even in the absence of a gamelan during rehearsal, these structural points would still be sung by the dance teacher so that the dancers understand how their movements synchronize with the music. Moreover, it would seem that the editors of the film even sought to synchronize the moment the dancers sit at 02:38 with the ketukan of the gong, but this synchronization was not exactly achieved, perhaps due to technical limitations of the time, or a mismatch between the speed of the piece and the speed of the film.

However, with the arrival of the witch Matah Gede at 02:39, we can see a very clear mismatch of music to character. Matah Gede is a very powerful witch, an old widow who must walk slowly and carefully with her cane. In contemporary calonarang, the music accompanying the entrance of Matah Gede is usually slower than that of sisia, in addition to providing a stark atmospheric contrast to the sisia dance. But in the case of this film, McPhee seems to have attempted to fit the Matah Gede movement using the piece for sisia. There are many correspondences in the film between the dance and the music that would seem to indicate an understanding of the proper relationship between the two, even though the sisia piece used would be improper for the dance of Matah Gede. For example, at 02:48, the dancer mekipek (suddenly looks up or to the other side) close to the gong, which is idiomatic and should be expected. At 02:52 the dancer seems to give an order to the gamelan players to angsel (play a loud flourish). This is seen when the dancer mejalan (walks) faster than before, it is followed by an angsel in the music. Finally, at 02:54 the dancer and music finish the angsel by mekipek of the dancer and a kendang accent, all synchronized. This would seem to indicate that McPhee at least understood what the relationship between the dance and the music should have been, but was perhaps limited to the Odeon and Beka sound recordings available to him, and was unable to choose a perfectly fitting piece for the exact situation on screen. However, given these rather severe limitations, it seems admirable that the resulting music fits as well as it does with the action on screen.

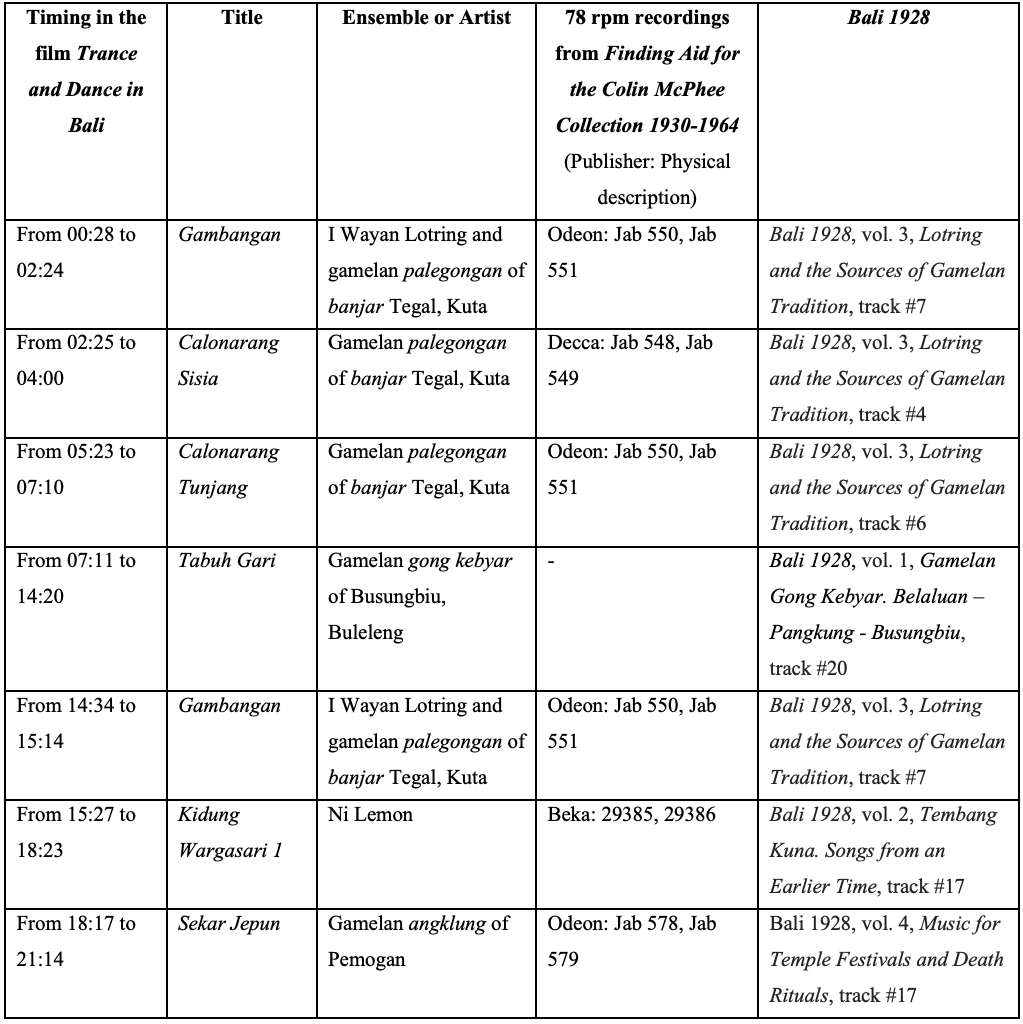

Calonarang Tunjang, on gamelan palegongan, from 05:23 to 07:10

Another strange music/dance juxtaposition occurs from 05:23 to 07:10, where we hear Calonarang Tunjang (taken from Odeon and Beka recordings published in 1929).29Finding Aid for the Colin McPhee Collection 1930–1964 mentions the title of the piece and the group played: Tjalon – Narang, Toendjang – Di Mainken Oleh. Pelegongan, Koeta on the 78 rpm Odeon: Jab 550, Jab 551 on side A. In Herbst release, this piece is on the album Bali 1928, vol. 3: Lotring and Sources of Gamelan Tradition, track #6. Typically, this piece would be heard when Rangda or Rarung30Rarung is the sisia of Rangda who usually has red color whereas Rangda has white color. is already on stage, but in the film, it is used at the moment when Rangda enters. Although it is in some basic sense acceptable to hear Calonarang Tunjang here, I suggest a more fitting choice would have been the gending Malpal of Tunjang Durga, beginning earlier, from 05:12 to 05:32 (Aryasa 1984, p. 71). This moment in the film, when the Pandung31Pandung is like a commander of an empire. In this context, it is the character who attacks Rangda before she comes onto the stage. attacks Rangda, is very important, and would always be accompanied by gending Malpal. But in the film, we hear no music (see Figure 3). The gending Malpal is a section of Tunjang Durga, where only two notes are repeated for a long time until Rangda reaches the middle of the stage. The cycle in one gongan should end on note dong.32Dong is a note name in Balinese gamelan. According to the Hindu religious concept in Bali, the note dong is the note related to the god Dewa Siwa (Bandem 1986, p 33). Dewi Durga, who is Dewa Siwa’s sakti,33Sakti in this context means the wife of a Dewa. Dewa is used to refer to a male god, Dewi for female god. manifests her power as Rangda.34See the appendix to find out more about the relationship between gamelan sound and Gods of Hinduism in Bali. Given these considerations, a more appropriate choice for the soundtrack at this point would have been gending Malpal from Tunjang Durga, rather than Calonarang Tunjang (Figure 4).

Figure 3: The Pandung attacking Rangda.35Taken from the film Trance and Dance in Bali at 05:12.

Figure 3: The Pandung attacking Rangda.35Taken from the film Trance and Dance in Bali at 05:12.

Figure 4: Gending Malpal of Tunjang Durga.

Figure 4: Gending Malpal of Tunjang Durga.

Following the scene of the Pandung attacking Rangda, at 05:32, I suggest what should then be heard is gending Bapang Durga, which is used for the Rangda ngelembar (dancing). Gending Bapang Durga has a slower tempo than the gending Malpal of Tunjang Durga, which implies that a strong and terrifying character will come (Figure 5). Bapang Durga would be played until Rangda is in the center of the stage, and then continued by playing gending Tunjang Rangda or the Calonarang Tunjang.36I suggest watching the sacred calonarang performance at https://youtu.be/7H78cXcEhL8 (accessed April 11, 2022).

Tabuh Gari, on gamelan gong kebyar, from 07:11 to 14:20

From 07:11 to 14:20, a short section of the piece Tabuh Gari was cut and looped to fill over seven minutes of soundtrack. The original recording of Tabuh Gari was taken from Odeon and Beka recordings.37I have not found this piece in Finding Aid for the Colin McPhee Collection 1930–1964. In the Herbst release, this piece is on the album Bali 1928, vol. 1: Gamelan Gong Kebyar: Belaluan – Pangkung – Busungbiu, track #20. Tabuh Gari in its original context is a tabuh penutup (closing piece) in the gamelan gong kebyar of Busungbiu.38In semar pegulingan, another type of gamelan, there is another piece also entitled Tabuh Gari, which is used as a tabuh petegak (opening instrumental piece). In gamelan gong kebyar of Busungbiu, “Tabuh Gari is an aural signal for the audience that it is time to leave” (Herbst 2009, p. 56).

Tabuh Gari is not a piece meant specifically for the calonarang performance, and when it is played, it functions as a closing piece. This piece has a unique composition because it adapts the composition style from other gamelan. For example, gong kebyar repertoire often adapts compositional techniques found in gamelan pelogongan. In the case of Tabuh Gari, we see characteristics of batel. Batel is usually used for a battle scene for Balinese dance. It is usually played using only the instruments gong, klentong, kajar, klenang, two kendang, kajar trenteng, and ceng-ceng. However, the ceng-ceng cannot be heard in the recording; “we might assume that ceng–ceng were omitted from most of the recordings because they would dominate the signal picked up by the microphone” (ibid.).

McPhee cut the middle part of the tabuh gari recordings to get the batel composition for Trance and Dance in Bali. From the full recording of tabuh gari (2 minutes 51 seconds), he cut the section of piece in the recordings (based on Bali 1928) from 00:56 to 01:27. The total recording material was 31 seconds, looped to become 7 minutes 31 seconds. This loop was made seamlessly to give the illusion of a more repetitious performance. The original 31-second piece consists of the full angsel one time, followed by the mejalan39The mejalan part in this context means a softer section part that is repeated many times. part until the kendang plays louder, which would normally signal to the group to continue to the next kebyar section. But because of the loop, the kendang signal ceases to function musically as a cue, and the section repeats itself.

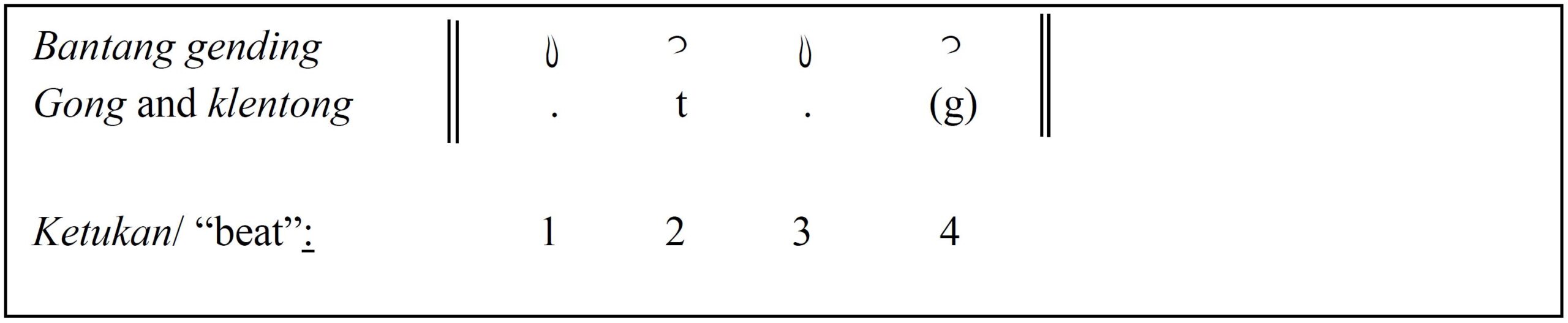

At this point in a contemporary ngurek calonarang, one should hear gending Kale on the note deng as a bantang gending (“structural melody”) with a very fast tempo (Figure 6). Gending kale is used when the patih (in Barong side) is attacking the Rangda and ngurek (stabbing themselves with keris). The piece is also dominated by the supernatural atmosphere note deng. Therefore, we can see that not only full pieces, but even their composite elements, down to the specific notes used, impart a symbolic function on the music heard. Thus, it is always helpful to consider the relationship between gamelan and religion in Bali.

Gambangan, on gamelan palegongan from 14:34 to 15:14

From 14:34 to 15:14, Gambangan is used again as a transition in the film. I presume that Gambangan is used as a tabuh penutup (closing piece), but it may have been chosen as a transition to accompany the captions. If it was used deliberately as a tabuh penutup, I do not consider it the best choice of music, since Gambangan was already played at the beginning of the film. It is odd in a calonarang to hear the same piece being played at beginning and the end in a performance. It is more common to hear different pieces, for example Gambangan at the beginning of the performance and tabuh Gilak bebarongan as tabuh penutup for the end of the performance. At 14:49, the camera moves away from the finished performance on the stage to bring us to the inside (what might be the Utama Mandala) of the temple. Gambangan continues until 15:16, which feels quite natural, since it is common for the musicians to continue playing the last piece of the performance after the characters and/or dancers have left the stage.

Kidung Wargasari I, for voice from 15:27 to 18:23

From 15:27 to 18:23, Kidung Wargasari I was taken from Odeon and Beka recordings published in 1929, sung by Ni Lemon.40Finding Aid for the Colin McPhee Collection 1930–1964 mentions the title of the piece and the singer: Lagoe Wargesari; ternjanji oleh, Ni Lemon dari Djangger Abian Timboel, Badoeng, Bali on the 78 rpm Beka: 29385, 29386 on side A. In Herbst release, this piece is on the album Bali 1928, vol. 2: Tembang Kuna. Songs from an Earlier Time, track #17. Only one singer was close to the microphone. In the film, this piece takes place after the end of the calonarang performance. This piece is still commonly sung and heard in Bali today. Herbst wrote that he met with Ni Madé Dantin (the niece of Ni Lemon): “They remembered the lyrics to the Wargasari […] but the lyrics recorded in 1928 are not used anymore” (Herbst 2014, pp. 79–80).

Kidung Wargasari is one of many types of Balinese vocal art, which is typically used for temple ceremonies. There are four classifications or types of Balinese vocal art: Sekar Rare, Sekar Alit or Macapat, Sekar Madya or Kidung, Sekar Ageng/Agung or Kakawin (Sinti 2011, p. 29). Of these four types, there are only a few Balinese vocal arts that use only voice as the main sound source, such as genjek and kecak. Wargasari is included in the group of Sekar Madya or Kidung. Kidung can have different functions depending on the lyrics.

McPhee might have chosen this piece to represent the situation in the temple. In Panca Gita, Kidung is very important for the religious ceremonies in Bali. In order to fully honour the culture, the meaning of the text from this specific Kidung would have to be known and taken into consideration to be sure that it is appropriate for the ceremony taking place. Even among pieces that sound similar, the text can vary dramatically. Wargasari, as a genre of music, can have a number of diverse functions: “Wargasari is a ritual genre of musical offering most often for dewa yadnya ‘ceremonies honouring deities’ as well as pitra yadnya ‘ceremonies honouring ancestors’ such as ngabén and nyekah ‘rituals associated with death and cremation’” (Herbst 2014, pp. 80–81). Alas, I do not know the full text used in this recording, and therefore cannot say with confidence whether this piece is truly an appropriate choice for the ceremony occurring in the footage. There are four stanzas found by Herbst, but from this fragment it is impossible to derive the specific meaning without the full text (ibid., p. 80).

Sekar Jepun, on gamelan angklung from 18:17 to 21:14

From 18:17 to 21:14, Sekar Jepun was taken from Odeon and Beka recordings published in 1929.41Finding Aid for the Colin McPhee Collection 1930–1964 mentions the title of the piece and the group played: Sekar Djepoen – di mainken oleh. Angkelong; Mogan on the 78 rpm Odeon: Jzb 578, Jab 579 on side B. In Herbst release, this piece is on the album Bali 1928, vol. 4: Music for Temple Festivals and Death Rituals, track #17. It is keklentangan style on gamelan angklung. The gamelan angklung is a type of Balinese ensemble using a slendro scale. It is used in its traditional setting for cremation and death-related ceremonies. Even though angklung is usually related to death ceremonies, angklung can be used inside a temple if it is the only kind of ensemble accessible, or if other kinds of ensembles would take too much space, provided the head of the village agrees to use angklung for non-death-related events. McPhee was aware that angklung is used for a cremation ceremony and odalan ceremony in the temple:

The gamelan angklung has always been a ceremonial orchestra of the village and was never employed, I have been told many times at the court. Heard at temple anniversaries and called upon to play at all village festivals, this essentially folk orchestra is perhaps the most useful ensemble to the smaller community, supplying bright ceremonial music of a lighter character than that of the gamelan gong. In smaller villages, especially in the Karangasem district, the gamelan angklung often replaces altogether the gamelan gong for ceremonial occasions, and is brought out only at the time of temple anniversaries and village cremation rites. (McPhee 1966, p. 234)

Some Balinese associate the sound of angklung with sad feeling. It depends on its primary function in their region. In the regency of Badung, Denpasar, Buleleng (North Bali), and most of Gianyar, angklung is mostly played for Pitra Yadnya death rituals: “Many people […] have said that hearing angklung reminds them of someone’s death and therefore brings out sad feelings” (Herbst 2015b, p. 69). Some villages in Badung regency (Kerobokan village) and Denpasar city (Kayumas Kelod), Karangasem, and Gianyar regency (Ubud and Sidan village), play angklung for odalan ceremony as well as Pitra Yadnya; therefore, we cannot generalize about emotional association of gamelan angklung (ibid.). Even though the village Kerobokan uses angklung in the temple, it will often use different repertoire from those used in Pitra Yadnya. The group usually plays angklung kebyar, it means that playing angklung uses kebyar style.42Angklung kebyar is used to play gamelan gong kebyar repertoire as well as kebyar musical style which is specially composed for gamelan angklung. The character of the angklung kebyar is more energetic and faster than angklung keklentangan. They also use a different type of kendang. Angklung kebyar uses kendang kekebyaran (bigger kendang) whereas angklung keklentangan uses kendang keklentangan (smaller kendang). Thus, in Kerobokan village one usually hears angklung kebyar for the temple ceremonies and angklung keklentangan (like the piece Sekar Jepun) for Pitra Yadnya or cremation.

There could be angklung during the Trance and Dance in Bali performance when there are people dying, like when we see the deceased baby or from Matah Gede’s pestilence at 04:31. But in the film, it is used when the people are coming out of the trance. It is remains unconfirmed whether the temple in the film used angklung for their ceremonies in the temple, and thus whether it would have been an appropriate choice for the soundtrack. But given that, as shown before, most of Gianyar regency (the regency of Pagutan) use angklung for cremation ceremonies, it seems unlikely that angklung would be the best choice for the temple ceremony seen in the footage.

Moreover, the angklung of this recording was played by the group of Pedungan village, and it is not the angklung from Pagutan where the footage was filmed. Angklung of Pedungan is used for Pitra Yadnya or cremation. More specific to this piece, Wayan Konolan in Herbst suggested that “[the Sekar Jepun piece] – still played by the musicians of Pemogan – is especially appropriate for rituals in the graveyard” (ibid., p.84). Based on that, it seems clear that the piece Sekar Jepun is not used for temple ceremonies like the one depicted in Trance and Dance in Bali.

Conclusion

Music in Bali straddles a complex web of relationships between music, dance, Hindu religious practices, ceremonies, regional practices, and the ongoing innovation which characterizes the cultural milieu in which Balinese music must be understood.

In Trance and Dance in Bali by anthropologists Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead, the music is not always appropriate for the calonarang performance or the ceremony which followed the performance. McPhee chose the music from Odeon and Beka recordings, which were not recorded in Pagutan where the footage was filmed. Thus, he used music from a different context and function than the calonarang in the film, because musical and ritual practices and usages are highly regionally specific in Bali. Ultimately, despite these issues, it is evident that McPhee had a strong understanding of Balinese music and its relationship to ritual and dance, otherwise he would not have been able to produce a soundtrack which fits as well as it does with the action on screen. This is clearly shown by the fact that most of the soundtrack in Trance and Dance in Bali is musically compatible with a calonarang performance. However, some of the pieces used would not be played in the context of a calonarang. To choose music for Balinese ceremonies, it is much too simplistic to merely consider the strictly musical elements of the pieces themselves, or even the basic relationship between the music and dance. Other considerations must come into play as well: the appropriateness of the music to the religious associations, the rules and practices of specific villages, and the social context of the music. Even though McPhee’s choices matched rhythmically, they were taken from pieces that do not belong in the calonarang context, and this completely changes their contextual meaning.

In the end, McPhee was nearly able to produce a fitting soundtrack, but the moments where he missed the mark are all the more disappointing because they come so close to producing an accurate portrayal of Bali at that time, in that place.

Acknowledgments

The idea for this paper first came up when I attended a seminar about gamelan under the guidance of Professor Jonathan Goldman (Université de Montréal). I am grateful to Professor Philippe Despoix (Université de Montréal) for all or his input, and assistance providing resources for this paper. In addition, I would like to thank Sarah Lecompte-Bergeron, Zachary Hazen, Evan O’Donnell, and Christopher Hull for helping and correcting my English writing.

Bibliography

Anonymous (2010), Bali 1928, vol. 1: Gamelan Gong Kebyar. Belaluan – Pangkung – Busungbiu, Gamelan gong kebyar of Busungbiu, Buleleng, Arbiter of Cultural Traditions.

Anonymous (2014), Bali 1928, vol. 2: Tembang Kuna. Songs from an Earlier Time, Ni Lemon (singer), Arbiter of Cultural Traditions.

Aryasa, I Wayan Madra (1984), Pengetahuan Karawitan Bali, Denpasar, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, Direktorat Jendral Kebudayaan, Proyek Pengembangan Kesenian Bali.

Bandem, I Made (1986), Prakempa. Sebuah Lontar Gambelan Bali, Denpasar, Akademi Seni Tari Indonesia Denpasar.

Bateson, Gregory, and Margaret Mead (1942), Balinese Character A Photographic Analysis, vol. 2, New York, The New York Academy of Sciences.

Belo, Jane (1961), Trance in Bali, New York, Columbia University Press.

Belo, Jane (1970), Traditional Balinese Culture, New York, Columbia University Press.

Clendinning, Elizabeth (2017), [Review of Bali 1928 I: Gamelan Gong Kebyar: Music from Belaluan, Pangkung, Busung-biu: The Oldest New Music of Bali; Bali 1928 II: Tembang Kuna: Songs from an Earlier Time; Bali 1928 III: Lotring and the Sources of Gamelan Tradition; Bali 1928 IV: Music for Temple Festivals and Death Rituals; Bali 1928 V: Vocal Music in Dance Dramas: Jangér, Arja, Topéng and Cepung from Kedaton, Abian Timbul, Sésétan, Belaluan, Kaliungu and Lombok; Bali 1928 Anthology: The First Recordings, by Allan Evans & Allan Evans], University of Illinois Press on behalf of Society for Ethnomusicology, vol. 61, no 1, pp. 166–178, https://doi.org/10.5406/ethnomusicology.61.1.0166.

Durington, Matthew, and Jay Ruby (2011), Made to Be Seen. Perspectives on the History of Visual Anthropology, Chicago and London, University of Chicago Press.

Henley, Paul (2013), “From Documentation to Representation. Recovering the Films of Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson,” Visual Anthropology, vol. 26, no 3, pp. 75–108.

Herbst, Edward (n. d.), Bali 1928 – Repatriating Bali’s Earliest Music Recordings, 1930s Films and Photographs, https://edwardherbst.net/, accessed 10 September 2020.

Herbst, Edward (2009), “Bali 1928 – Volume I – Gamelan Gong Kebyar. Music from Belaluan, Pangkung, Busungbiu,” Arbiter of Cultural Traditions, pp. 1–66, https://edwardherbst.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Bali-1928-vol-I-Gamelan-Gong-Kebyar-Herbst.pdf, accessed 5 May 2022.

Herbst, Edward (2014), “Bali 1928 – Volume II. Tembang Kuna: Songs from an Earlier Time,” Arbiter of Cultural Traditions, pp. 1–116, https://edwardherbst.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Bali-1928-vol-II-Tembang-Kuna-Herbst.pdf, accessed 5 May 2022.

Herbst, Edward (2015a), “Bali 1928 – Volume III. Lotring and the Sources of Gamelan Tradition,” Arbiter of Cultural Traditions, pp. 1–119, https://edwardherbst.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Bali%201928%20vol%20III%20Lotring%20and%20the%20Sources%20of%20Gamelan%20Tradition%20Herbst.pdf, accessed 5 May 2022.

Herbst, Edward (2015b), “Bali 1928 – Volume IV. Music for Temple Festivals and Death Ritual,” Arbiter of Cultural Traditions, pp. 1–98, https://edwardherbst.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Bali%201928%20vol%20IV%20Music%20for%20Temple%20Festivals%20and%20Death%20Rituals%20Herbst.pdf, accessed 5 May 2022.

Jacknis, Ira (1988), “Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson in Bali. Their Use of Photography and Film,” Cultural Anthropology, vol. 3, no 2, pp. 160–177.

Kunst, Jaap (1974), Ethnomusicology. A Study of Its Nature, Its Problems, Methods and Representative Personalities to which is Added a Bibliography, Springer Netherlands.

Lotring, I Wayan (2015), Bali 1928, vol. 3: Lotring and the Sources of Gamelan Tradition, I Wayan Lotring (kendang), gamelan palegongan of banjar Tegal, Kuta, Arbiter of Cultural Traditions.

McPhee, Colin (1946), A House in Bali, New York, The John Day Company.

McPhee, Colin (1966), Music in Bali. A Study in Form and Instrumental Organization in Balinese Orchestral Music, New Haven and London, Yale University Press.

McPhee, Colin (2009), “Finding Aid for the Colin McPhee Collection 1930-1964,” UCLA Ethnomusicology Archive, http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt9c6029pt, accessed 9 November 2020.

Mead, Margaret, and Gregory Bateson (1951), Trance and Dance in Bali, Library of Congress.

Murdaningsih, Ni Kadek Ary, Ni Nyoman Sri Widiasih, and I Made Adi Brahman (2017), “Pementasan Calonarang pada Piodalan di Pura Dalem Desa Pakraman Umanyar Tamanbali Bangli. Perspektif Teologi Hindu,” Jurnal Penelitian Agama Hindu Institut Hindu Dharma Negeri Denpasar, vol. 1, no 1, pp. 53–56.

Putra, Made Pradnyana, Ketut Sedana Arta, and Desak Made Oka Purnawati (2017), “Barong Ket Sebagai Seni Pertunjukan di Desa Batubulan, Sukawati, Gianyar, Bali (Latar Belakang dan Potensinya Sebagai Sumber Sejarah di SMA),” Widya Winayata. Jurnal Pendidikan Sejarah, vol. 8, no 2, pp. 1-10.

Sinti, I Wayan (2011). Gambang Cikal Bakal Karawitan Bali, Denpasar, TPS Books.

Suartaya, Kadek (2011), Janda Jantan Ni Calonarang, Mengerang Garang Menantang Penguasa, www.isi-dps.ac.id/berita/janda-jantan-ni-calonarang-mengerang-garang-menantang-penguasa/?doing_wp_cron=1599867615.8878560066223144531250, accessed 11 September 2020.

Sudirana, I Wayan (2019), “Colin McPhee and Balinese Music. A Short Bibliography,” Journal of Music Science, Technology, and Industry, vol. 2, no 1, pp. 37–48.

Tenzer, Michael (2000), Gamelan Gong Kebyar. The Art of Twentieth-Century Balinese Music, Chicago and London, The University of Chicago Press.

Wirawan, Komang Indra (2019), “Penanaman Nilai Pendidikan Karakter Melalui Seni Pertunjukan Dramatari Calonarang. Kajian Teori Kaca Rasa Taksu,” Seminar Nasional “Penanaman Nilai-nilai Pendidikan melalui Seni Budaya Nusantara” Fakultas Pendidikan Bahasa dan Seni, IKIP PGRI Bali, pp. 69–79.

Wirawan, Komang Indra (2020), “The Magical Chain of Calonarang Dance Drama Performances,” Jurnal of Critical Review, vol. 7, no 4, pp. 2474–2480.

Annex

Lontar43Lontar is a palm leaf manuscript. Prakempa gives a list of the gods, and their associated directions, colours, and tones in Balinese gamelan and voice (Bandem 1986, p. 33).

- In the east direction, God’s name is Sang Hyang Iswara (written Içwara), the colour is white, the aksara is “Sang” (written “Ça”), and the tone is “dang.”

- In the southeast direction, God’s name is Sang Hyang Mahesora, the colour is pink or dadu, the aksara is “Na,” and the tone is “ndang.”

- In the south direction, God’s name is Sang Hyang Brahma, the colour is red, the aksara is “Bang” (written “Bha”), and the tone is “ding.”

- In the southwest direction, God’s name is Sang Hyang Rudra (written “Ludra”), the colour is orange, the aksara is “Mang” (written “Ma”), and the tone is “nding.”

- In the west direction, God’s name is Sang Mahadewa, the colour is yellow, the aksara is “Tang” (written “Ta”), and the tone is “deng.”

- In the northwest direction, God’s name is Sang Sangkara, the colour is green, the aksara is “Sing” (written “Çi”), and the tone is “ndeng.”

- In the north direction, God’s name is Sang Hyang Wisnu, the colour is black, the aksara is “Ang” (written “A”), and the tone is “dung.”

- In the northeast direction, God’s name is Sang Hyang Sambu, the colour is blue, the aksara is “Wang” (written “W”), and the tone is “ndung.”

- In the center, Gods’ names are Sang Hyang Siwa (written “Çiwa”) and Sang Hyang Budha, the colour is panca warna or brumbun (five colours) , the aksara are “Ing” (written “I”) and “Y” or “Ya”, and the tones are “dong” (Siwa) and “ndong” (Budha) (ibid.).

The sounds of gamelan are also a representation of the gods. When gamelan is played for ceremonies, Balinese will make (ngaturang banten) offerings to the gods beforehand. In order to associate a gamelan composition with the gods, the composition usually has one note that is played more frequently in the composition. The note chosen is also used as the final note played together with a gong at the end of a cycle or piece. For example, to relate a gamelan piece to Shang Hyang Siwa, the composition would have more dong tone and it would end with the dong tone as well.

Figure 7: Gamelan tones and gods.44Draw-adapted from Bandem 1986, p. 42.

Figure 7: Gamelan tones and gods.44Draw-adapted from Bandem 1986, p. 42.

| RMO_vol.9.1_Suryanegara |

Attention : le logiciel Aperçu (preview) ne permet pas la lecture des fichiers sonores intégrés dans les fichiers pdf.

Citation

- Référence papier (pdf)

I Putu Arya Deva Suryanegara, « Trance and Dance in Bali (1951). On the Musical Selections of Mead and Bateson’s Film », Revue musicale OICRM, vol. 9, no 1, 2022, p. 93-113.

- Référence électronique

I Putu Arya Deva Suryanegara, « Trance and Dance in Bali (1951). On the Musical Selections of Mead and Bateson’s Film », Revue musicale OICRM, vol. 9, no 1, 2022, mis en ligne le 27 juin 2022, https://revuemusicaleoicrm.org/rmo-vol9-n1/trance-and-dance-in-bali/, consulté le…

Auteur

I Putu Arya Deva Suryanegara, Université de Montréal

Kerobokan (Bali) based composer I Putu Arya Deva Suryanegara is currently studying musique: option composition et création sonore at Université de Montréal. He graduated from Indonesian Institute of the Arts (ISI) Denpasar in 2018. He has built on an expert foundation in traditional gamelan to explore and experiment with new departures. This includes the production of a variety of new works and the founding of the collective Naradha Gita (Nagi). He is also a guest artistic director of the Ensemble de musique balinaise Giri Kedaton.

Notes

| ↵1 | The film can be watched here: https://www.loc.gov/item/mbrs02425201/ (accessed April 11, 2022). |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | I come to this research situated as a Balinese researcher, composer, and musician who has studied the musical practices of my home village in Kerobokan, Bali since I was a child. I do not want to overstate my expertise in relation to the subject matter—anyone claiming to have a final authoritative opinion regarding musical practices from any given region of Bali, let alone practices that took place roughly 100 years ago, would be misrepresenting what can be known. Musical and ritual practices in Bali are extremely varied and context dependent, and as living practices, they develop over time and change as they are passed from generation to generation. However, there are common threads which can be discussed and about which claims can be made, and it is these common threads that will help shed some light on the ways these musical practices have developed over time. |

| ↵3 | Gamelan is a traditional musical ensemble from the islands of Bali and Java. In this paper, the word “gamelan” always refers to the Balinese gamelan. |

| ↵4 | Pagoetan village, which Mead and Bateson reference in the film, is a banjar (localized community organizations in Balinese society). Pagutan is in Batubulan village today. |

| ↵5 | Patih refers to the people who attack Rangda using a keris (ceremonial knife), regardless of gender. In this story, patih are on the side of Pandung and Barong. |

| ↵6 | See pages 96-97 for the definition of dramatari calonarang. |

| ↵7 | The music may not have been added to the film until 1950, when Mead began to work with Josef Bohmer to edit the footage originally taken in 1937 and 1939 (Jacknis 1988, p. 70). |

| ↵8 | The Odeon, Beka, and Decca albums which McPhee possessed merely note the title of pieces and the name of artists or groups involved. One can assume the research at the time was less rich than later provided by Herbst. |

| ↵9 | See pages 96-97 about calonarang. |

| ↵10 | There exist some inconsistencies in the naming conventions between what is found in Belo’s description, and what is seen today in the calonarang story. It is unclear whether, at the time of the recording, these names were used interchangeably or, as is seen today, they refer to slightly different instances. For example, the story takes place during the reign of King Prabu Siwasipoerna, rather than King Erlangga, as is seen today. The witch is also given a different name, Ni Doekoeh Batoer, whereas in calonarang today she is named Walu Nateng Dirah. |

| ↵11 | The penyungsung is a person chosen by the holy spirit inhabiting the costume, in this case Rangda or Barong. They offer their body for the kerauhan from the deities. Under their possession, the penyungsung will dance, participate in procession, and take part in the calonarang ceremony as an incarnation of a holy spirit. |

| ↵12 | It seems that they were permitted to enter the main part of the temple, where some temples do not allow outsiders to enter the sacred part. It depends on the rule in each village. |

| ↵13 | McPhee might not have given this recording or album to the UCLA archive. |

| ↵14 | The five Bali 1928 volumes can be found at https://bali1928.net/bali-1928-on-spotify/ or https://edwardherbst.net/?page_id=61 (accessed April 11, 2022). |

| ↵15 | The time codes used throughout the text are based on the online version of the film: www.loc.gov/item/mbrs02425201/ (accessed April 11, 2022). |

| ↵16 | Herbst found a total 111 78 rpm disks of Odeon and Beka. He began to publish his research from 2009 until 2015 including the Odeon and Beka album 65s. Herbst published the recordings in five volumes: Bali 1928, vol. 1: Gamelan Gong Kebyar Music from Belaluan, Pangkung, Busungbiu; Bali 1928, vol. 2: Tembang Kuna. Songs from an Earlier Time; Bali 1928, vol. 3: Lotring and the Sources of Gamelan Tradition; Bali 1928, vol. 4: Music for Temple Festivals and Death Rituals; Bali 1928, vol. 5: Vocal Music in Dance Dramas. Jangér, Arja, Topéng & Cepung. |

| ↵17 | Concerning the term of tokoh in (Suartaya 2011). |

| ↵18 | Translated by the author. |

| ↵19 | Finding Aid for the Colin McPhee Collection 1930–1964 mentions the title of the piece and the group playing: Peloegon (gambangan) – Di Mainken Oleh: Pelegongan, Koeta on the 78 rpm Odeon: Jab 550, Jab 551 on side B. In the Herbst release, this piece is on the album Bali 1928, vol. 3: Lotring and Sources of Gamelan Tradition, track #7. |

| ↵20 | Tabuh bebarongan is a composition on gamelan palegongan and bebarongan using a medium kendang with a panggul or mallet. |

| ↵21 | Kotekan is interlocking rhythmical patterns proper to Balinese gamelan. |

| ↵22 | Finding Aid for the Colin McPhee Collection 1930–1964 mentions the title of the piece and the group played: Tjalon – Narang, Sisija – Di Mainken Oleh. Pelegongan, Koeta on the 78 rpm Decca: Jab 548, Jab 549 on side A. In Herbst release, this piece is on the album Bali 1928, vol. 3: Lotring and Sources of Gamelan Tradition, track #4. |

| ↵23 | The sisia are female disciples of the witch Matah Gede, and in this opening dance they are seen in beautiful human form with their hair long and flowing (performed by young girls, age 11 or thereabouts, into the 1930s) (Herbst 2015a, p. 43). |

| ↵24 | Matah Gede is a tokoh who is very powerful and transforms into Rangda. |

| ↵25 | Deng is the name of a note in Balinese gamelan. The five notes on Balinese gamelan are ding, dong, deng, dung, and dang. |

| ↵26 | I believe this concept is well known to Balinese gamelan scholars. If I remember correctly, the first time I heard it during a gamelan theory class was directed by I Gusti Ngurah Padang at SMKN 3 Sukawati. |

| ↵27 | In this context, ketukan is a “beat” in Balinese gamelan through a kajar instrument. |

| ↵28 | See Michael Tenzer’s explanation of colotomic structure (Tenzer 2000, p. 7). |

| ↵29 | Finding Aid for the Colin McPhee Collection 1930–1964 mentions the title of the piece and the group played: Tjalon – Narang, Toendjang – Di Mainken Oleh. Pelegongan, Koeta on the 78 rpm Odeon: Jab 550, Jab 551 on side A. In Herbst release, this piece is on the album Bali 1928, vol. 3: Lotring and Sources of Gamelan Tradition, track #6. |

| ↵30 | Rarung is the sisia of Rangda who usually has red color whereas Rangda has white color. |

| ↵31 | Pandung is like a commander of an empire. In this context, it is the character who attacks Rangda before she comes onto the stage. |

| ↵32 | Dong is a note name in Balinese gamelan. |

| ↵33 | Sakti in this context means the wife of a Dewa. Dewa is used to refer to a male god, Dewi for female god. |

| ↵34 | See the appendix to find out more about the relationship between gamelan sound and Gods of Hinduism in Bali. |

| ↵35 | Taken from the film Trance and Dance in Bali at 05:12. |

| ↵36 | I suggest watching the sacred calonarang performance at https://youtu.be/7H78cXcEhL8 (accessed April 11, 2022). |

| ↵37 | I have not found this piece in Finding Aid for the Colin McPhee Collection 1930–1964. In the Herbst release, this piece is on the album Bali 1928, vol. 1: Gamelan Gong Kebyar: Belaluan – Pangkung – Busungbiu, track #20. |

| ↵38 | In semar pegulingan, another type of gamelan, there is another piece also entitled Tabuh Gari, which is used as a tabuh petegak (opening instrumental piece). |

| ↵39 | The mejalan part in this context means a softer section part that is repeated many times. |

| ↵40 | Finding Aid for the Colin McPhee Collection 1930–1964 mentions the title of the piece and the singer: Lagoe Wargesari; ternjanji oleh, Ni Lemon dari Djangger Abian Timboel, Badoeng, Bali on the 78 rpm Beka: 29385, 29386 on side A. In Herbst release, this piece is on the album Bali 1928, vol. 2: Tembang Kuna. Songs from an Earlier Time, track #17. |

| ↵41 | Finding Aid for the Colin McPhee Collection 1930–1964 mentions the title of the piece and the group played: Sekar Djepoen – di mainken oleh. Angkelong; Mogan on the 78 rpm Odeon: Jzb 578, Jab 579 on side B. In Herbst release, this piece is on the album Bali 1928, vol. 4: Music for Temple Festivals and Death Rituals, track #17. |

| ↵42 | Angklung kebyar is used to play gamelan gong kebyar repertoire as well as kebyar musical style which is specially composed for gamelan angklung. |

| ↵43 | Lontar is a palm leaf manuscript. |

| ↵44 | Draw-adapted from Bandem 1986, p. 42. |