Rutherford Chang.

The Record Collector as Artist-Curator

Jim Drobnick

| PDF | CITATION | AUTHOR |

Abstract

Record collectors judge their acquisitions by condition and rarity. Artist Rutherford Chang undermines such norms by seeking as many copies as possible, in whatever state, of one of the best-selling albums of all time: The Beatles (1968), or “the White Album.” After 50+ years, many of the 3 million numbered albums have become worn due to handling but also because of writing and drawing. Since 2013, the artist has accumulated over 3,200 copies—most that are chafed, scribbled upon, stained, or moldy. This article examines Chang’s project and its interrogation of fan appreciation and practices of consumption; the affects of aging and patina; the notion of collaborative creativity; and the role of the artist-curator. In amassing such a diverse array, We Buy White Albums highlights the variability of a mass-produced commodity while demonstrating the effectiveness of an artist-curatorial methodology to raise issues about the life and care of record albums.

Keywords: artist-curator; Rutherford Chang; fan creativity; patina; record collecting; The White Album (The Beatles).

Résumé

Les collectionneurs de disques jugent leurs acquisitions en fonction de leur état et de leur rareté. L’artiste Rutherford Chang ébranle ces normes en recherchant le plus grand nombre possible d’exemplaires, quel que soit leur état, de l’un des albums les plus vendus de tous les temps : The Beatles (1968), ou l’« Album blanc » (White album). Après plus de 50 ans, bon nombre des 3 millions d’albums numérotés se sont usés par la manipulation, mais aussi par l’écriture et le dessin. Depuis 2013, l’artiste a accumulé plus de 3200 exemplaires, dont la plupart sont abîmés, gribouillés, tachés ou moisis. Cet article examine le projet de Chang et son interrogation à propos de l’appréciation des fans et les pratiques de consommation, les affects du vieillissement et de la patine, la notion de créativité collaborative et le rôle de l’artiste-commissaire. En rassemblant une telle diversité, We Buy White Albums met en évidence la variabilité d’un produit de masse tout en démontrant l’efficacité d’une méthodologie d’artiste-commissaire pour soulever des questions sur la vie et l’entretien des albums.

Mots clés : Album blanc (The Beatles) ; artiste-commissaire ; Rutherford Chang ; collection de disques ; créativité des fans ; patine.

Figure 1: Rutherford Chang, We Buy White Albums (2013–ongoing), installation view of bins, vinyl albums and record player at the exhibition Spin, KMAC Museum, Louisville (2018). Photo: courtesy of the artist.

Record collectors judge their acquisitions by condition and rarity. Mint copies and limited editions typically arouse the greatest desire and fetch the highest prices. Artist Rutherford Chang undermines such normative principles by seeking as many copies as possible, in whatever state, of one of the best-selling albums of all time: The Beatles (1968), more commonly known as “the White Album” because of its minimalist cover design. Given that 3 million albums were produced in the original numbered pressing, there is no scarcity of copies available. And after 50+ years, many of those covers have gathered a patina due to handling and storage but also because of writing and drawing. Since 2013, when Chang initiated We Buy White Albums, the artist has obtained over 3,200 albums—some that are in fine condition, but most that are worn, scribbled upon, damaged or moldy—which he periodically displays in a record shop-like format. Such an interactive exhibitionary component transforms Chang’s role into that of an artist-curator, where collecting becomes a conceptual and interrogatory gesture. This article examines Chang’s project and its ramifications for investigating the affects of aging, patina, and use of mass commodities; emphasizing fan appreciation and the practices of popular consumption; exploring the notion of collaborative, distributed creativity; and foregrounding the potential of the artist-

curator role.

Chang’s collecting began innocently enough. After purchasing one White Album, the artist noticed another copy with a different pattern of wear on the jacket, and from then on he was induced to keep collecting (Yulman 2017). Obsessiveness and painstaking effort appear throughout Chang’s work. His Alphabetized Newspaper (2004), for instance, cuts up and reorganizes the words appearing on a New York Times front page. Rendered into piecemeal alphabetical order, the headlines and articles still make an awkward type of sense, though readers will need to ruminate on the multiple possibilities for meaning. Class of 2008 (2012) excerpts 4,200 stipple portraits (also known as hedcuts) from the Wall Street Journal, printed during the infamous year of the financial crisis. Arranged like head shots in a high school yearbook, the collection convenes a book of shame for the advocates of ruinous policies leading to bank failures and the global recession. Game Boy Tetris (2016) records every game played by the artist. In over 1,500 attempts, he eventually claimed the #2 spot in the world (and beating Steve Wozniak in the process).1For more on these works, see Yulman (2017), Beaumont-Thomas (2016) and Mehrens (2016). Chang’s interest in systems and methods of organizing disparate materials also apply to the artifacts of his own life. For instance, he has kept every receipt for over a decade in chronological order and maintains a list of every flight he has taken (Falcone 2014). Even though these works utilize the different media of collage, appropriation, and performance, they characterize how Chang’s practice involves small, meticulous gestures with familiar, everyday materials that eventually unite to create a compelling effect.

The White Album was a fortuitous choice. Besides being one of the iconic albums of the 1960s, it was already an editioned multiple. Pop artist Richard Hamilton, a friend of Paul McCartney, was tasked with designing the cover to the Beatles’ ninth album. In contrast to the colorful, maximalist collage produced by Peter Blake for Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967), Hamilton chose a minimalist jacket that eschewed the typical expectations of a record cover: no title, no portrait of the band members, no artful graphics.2Cf. Inglis (2001, p. 89) and Womack (2020, p. 2). Inside the album, however, were photographs of the band and a poster that would appeal to the traditional consumer. See Luke (2018a, 2018b) and Jones (2020). Only the Beatles, the most famous of Sixties’ groups, could afford disavowing such a basic promotional opportunity. The cover design was not only an innovative pop cultural item, but one also aligned with the vanguard movements of minimalism, conceptual art, and institutional critique. Critics have labeled the cover as non- or anti-art,3See Lubell (2020) and Littlejohn (2020, p. 90). much like terms levied against Robert Rauschenberg’s White Painting (1951) or Art & Language’s Map of a Thirty-Six Square Mile Surface Area of the Pacific Ocean West of Oahu (1967). These two examples of negation and absence achieved different effects: for Rauschenberg, evacuating content on the picture plane, so that shadows from the painting’s environment occupied the surface, undermined the ideology of the artist’s expressiveness; for Art & Language, denying the information that a map usually provides questioned the sufficiency of epistemological structures.4On Rauschenberg, see Staff (2015, pp. 82–84); on Art & Language, see Harrison (1991). Hamilton’s cover performed a similar type of dual subversion regarding content and information, here employing high art strategies upon the popular format of the record cover. In 1968, the contemporary notion of editioned multiples was barely a decade old and operated mainly on the margins of the art world.5While multiples had been produced earlier, the modern notion of the multiple can be traced to Editions MAT (1959) and early 1960s Fluxus productions. See Bury (2001) and Dyment and Elgstrand (2012). Yet, even at this early stage in the history of multiples, Hamilton arguably created the most popular, democratically available, and widely distributed example—the incongruous appearance of millions of copies of a numbered edition (Sexton 2017). The album’s ubiquity, however, overshadowed its artistic status as a multiple. Fittingly, Chang’s We Buy White Albums saves Hamilton’s design from being merely a stealth artwork.6Special limited editions are now a common marketing technique in popular music, as is the collaboration with visual artists to design covers.

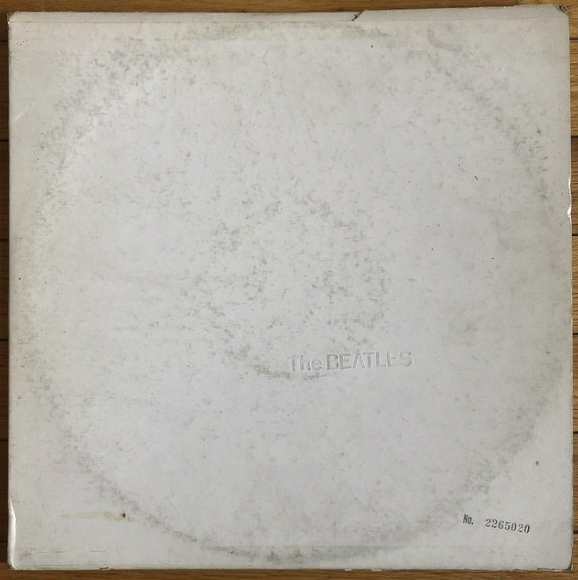

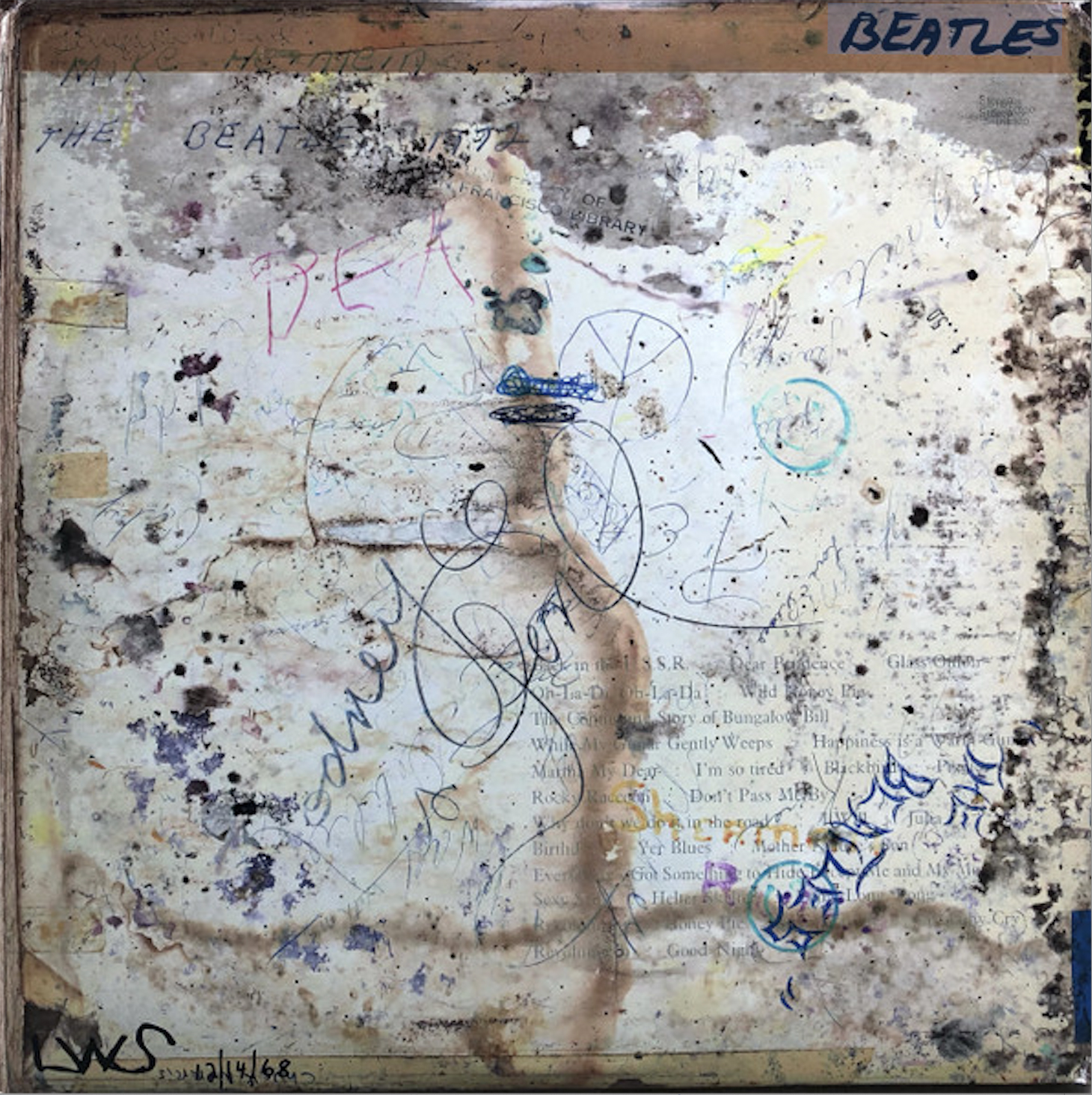

Figures 2-3: Rutherford Chang, We Buy White Albums (2013–ongoing), view of album covers showing scuffing and stains. Photos: courtesy of the artist.

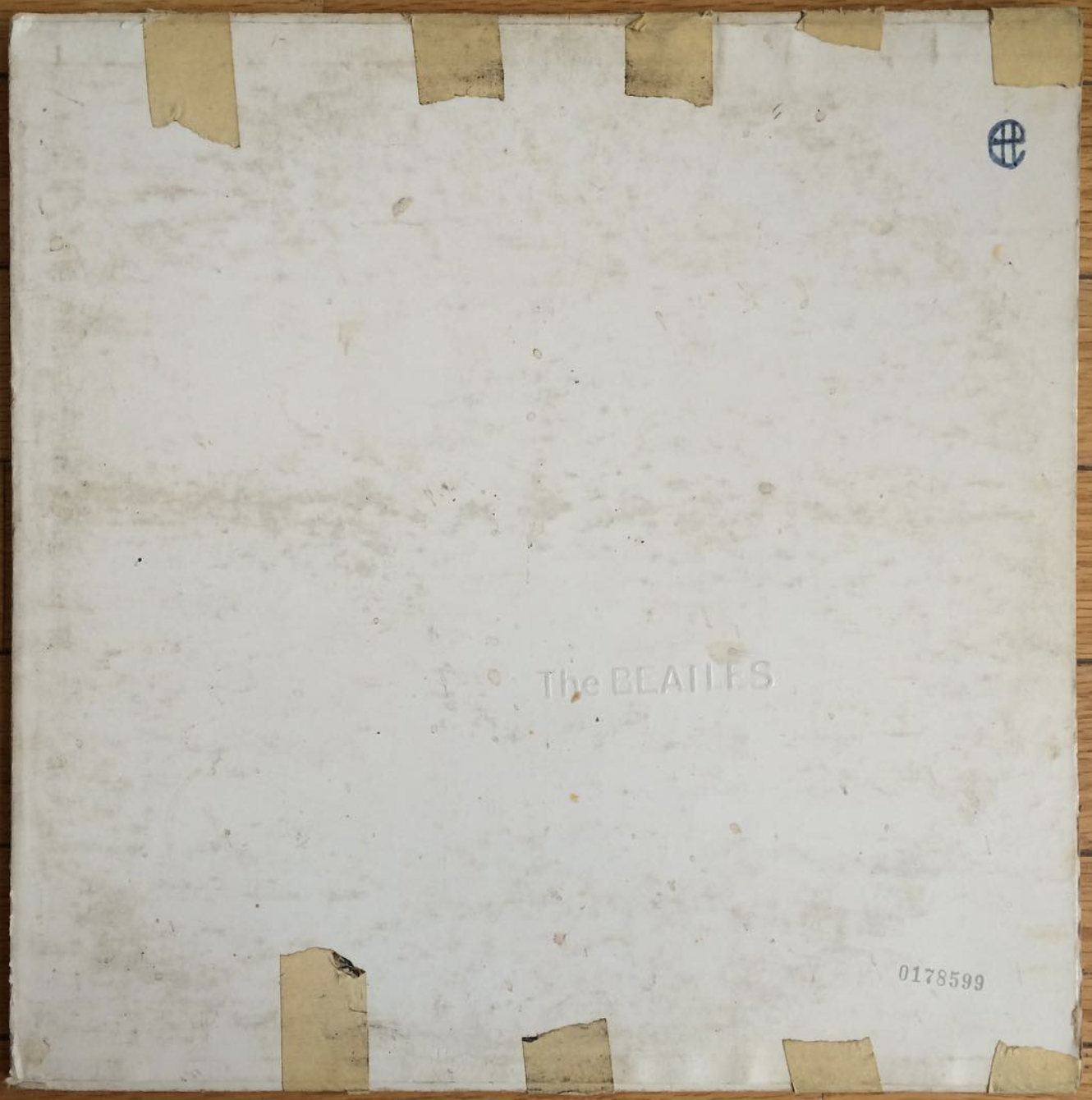

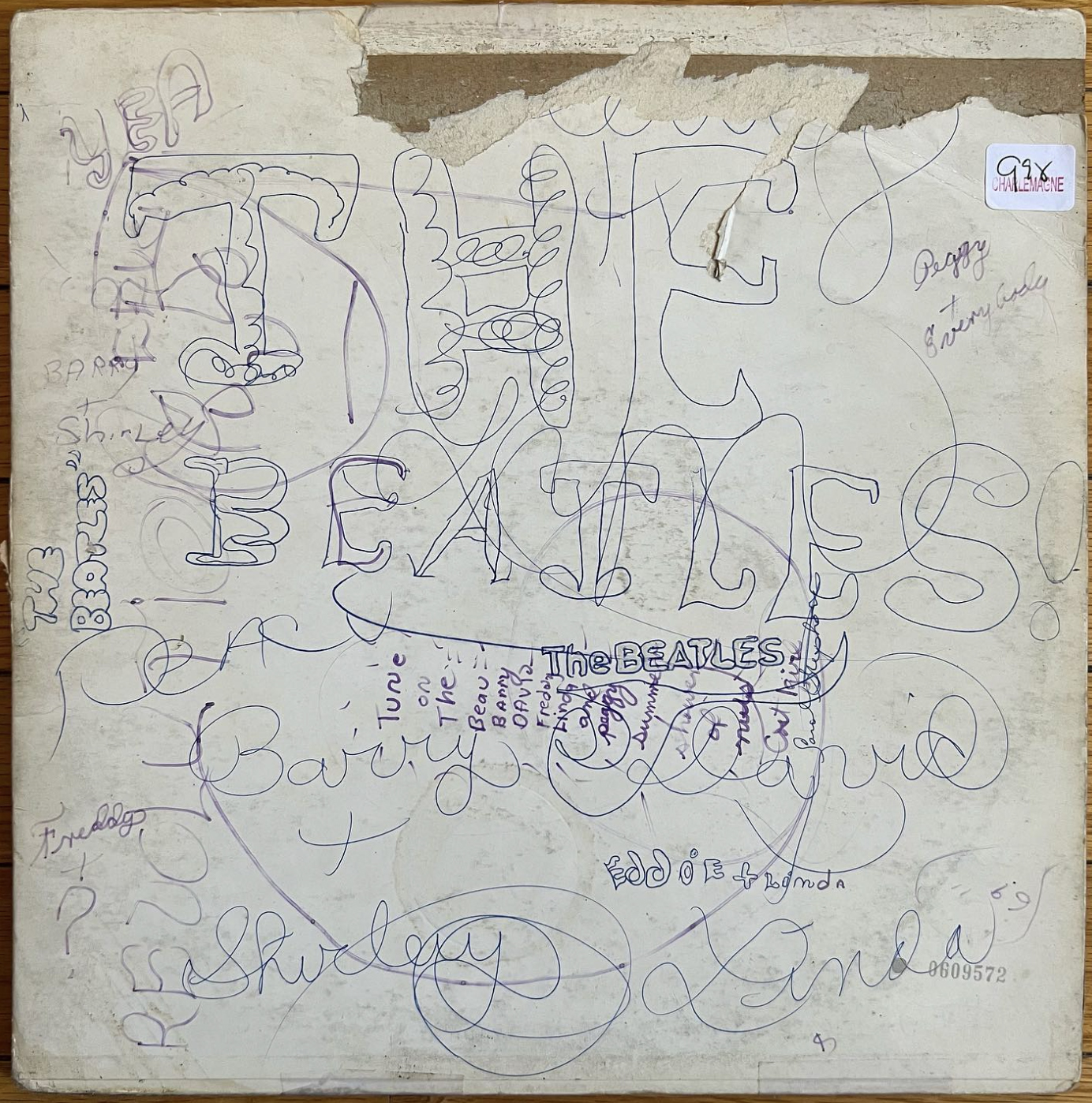

The patina of the White Albums’ jackets was the first aspect that attracted the artist, and one of the mainstays of press coverage on Chang’s project. In the era of digital, disembodied music, apparently obsolete material objects carry a powerful affect through their patina.7Chang’s collecting vinyl may be seen as a response to lack of physicality with digital forms of music, but as commentators in Paz (2013) point out, vinyl’s decline since the introduction of mp3s and streaming has not been total, for it has resurged several times. While scuff marks, yellowing, ring wear, and other evidence of handling detract from the value of an album to a “true” vinyl collector, the patina stores the history of the object through surface and texture. As the artist notes, the records may have originated in identical factory conditions, but through the years of their “individual journeys” they each have become unique.8Chang in Maly (2013); see also Yulman (2017, p. 1). The whiteness of the cover represents “a format impossible to keep pristine,” and so it inevitably becomes sullied (Maly 2013). Chang courts the relishing of patina by offering the albums in bins (where visitors can flick through them), by arranging jackets on the wall (like the favorites picked by record store staff), and by posting covers on Instagram (where each acquisition is documented in sequence) (Chang n.d. a). By being touched and handled in the exhibitions of We Buy White Albums, the artist fosters the ongoing development of patina by the accrual of more fingerprints and scuffing.

Patina, however, is usually considered a positive feature of antiques, not mass-market consumer items, which tend to favour shiny newness. Chang’s display of White Albums thus transplants the affectiveness and significance of patina from the realm of antique collectors to that of popular culture. In art historian/antique dealer Leon Rosenstein’s analysis, patina harbours a special aesthetic appeal because it “mak[es] aged things more complex, as when […] stains, small chips, tiny cracks [create] irregularities and asymmetries that are, in their visual and tactile conditions, more interesting and stimulating to the imagination than uniform regularity” (Rosenstein 2009, p. 32). For individual albums, the scuff marks may seem like unfortunate blights despoiling what should have been kept spotless, but when different abraded albums are brought together and compared, the fascination of different patinas is magnified. One can see what queer theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick (2003) terms “texxture”—the extra “x” denoting the affect of depth when the materiality and tangibility of an object conveys more information than normally expected. In Chang’s work, the damage on the jackets recognizes the inescapable breaking down of paper and the subtle beauty and charm of its rough, mottled, vexed surfaces. Patina brings forth an authenticity and character that could only be achieved through a gradual accretion over many years.

Patina confirms the five-decade journey of each album’s survival: the scrapes and blotches on the covers connect present-day viewers to the era in which the record originated, as well as to the intervening years and events. For Rosenstein, patina is a sensuous materialization of “persistent existence” and “the weight of history.” Patina thus not only functions as a recollection of the past; it evocatively summons the awareness of time passing and the feeling of historicity (Rosenstein 2009, p. 33). That passing of time simultaneously implicates the White Album, the members of the Beatles, and the owners of the records themselves. We Buy White Albums acknowledges the album as an historic and iconic work, but not one that is immutable or eternal—the reputation of the Beatles’ masterpiece is as vulnerable to shifting tastes in music as it is to the deterioration of the jacket. The break-up of the band itself, less than a year after the album’s release, evokes another affective dimension to the patina, namely the frailty of the Beatles as a group and as individuals.9The frailty of memory is raised by the premise of the Danny Boyle film Yesterday (2019), which imagines a time when the Beatles’ music has been wiped from cultural memory, except for a few individuals. With the untimely death of Lennon, the passing of Harrison, and the wrinkles on the faces of Starr and McCartney, the fifty plus years of patina on the covers conjures the pathos of mortality and loss.10Maly (2013) likens the covers to serving as memento mori. For art historian Karin Wagner, patina creates an affinity between people and objects by showing that both embody a life history and that being old retains value. Patina thus serves as a “metaphor for human imperfection” and aids in the acceptance of flaws and the process of aging (Wagner 2019, pp. 271–72). The patina of the White Albums, then, stands in for time’s effects on the human skin and provides a symbol of endurance and resilience.11Another project focusing on the build-up of patina is Christian Marclay’s Record Without a Cover (1985), which involved a series of vinyl LPs released without packaging. The resulting scrapes and scratches from shipping and handling are intentional and integral to the work.

Figures 4-5: Rutherford Chang, We Buy White Albums (2013–ongoing), view of album covers showing mold and repairs. Photos: courtesy of the artist.

Patina can also carry oppositional and political meanings, as articulated by media scholars Adrian and Inge Konik. Besides being anti-consumerist by not adhering to the fetishization of the new and the novel, a focus on patina emphasizes a connection to the past, especially to others who have existed in the near and distant past. The well-worn surfaces, each with their own character, propose a sense of “companionship” with the fullness of time that transient and trendy items never could deliver (Konik & Konik 2013, pp. 133, 144). Chang’s collecting, organizing, and displaying of the records enacts what could be considered a form of caring – recognizing the humanity materialized in the patina and the experience of passing time that affects both objects and people. For the Koniks, patina kindles a type of meditativeness, one that involves memorializing and ritualistic efforts: by appreciating the subtleties of patina, one is linked to a long view of history beyond that of “isolated individuality” (ibid., pp. 147–48). It is through such a conjoining with absent others—generations past and those in the future alike—that an ethos of responsibility arises, which the Koniks call “curatorial consumption.” Rather than admiring objects for their intoxicatingly new qualities, curatorial consumption favours the “critical thought which they precipitate” (ibid.). So it is with Chang’s collection—the patina of the records instills a sense of fascination that is implicitly focused on the ethos of shared histories.

Another conspicuous affect involves patina’s passage into the abject. Paper is an ephemeral material liable to such degradations as splits, tears, stains, foxing, and mold. Chang’s collection includes many records disfigured by taped-up scars and messes that are seemingly unable to be cleaned. Such abject states communicate a sense of trauma, neglect, and abuse, and it is a wonder that some owners even saved or tried to sell the records. As Wagner writes, patina is desirable, “but only to a certain extent”; that is, until it ruins the object totally (Wagner 2019, p. 263). We Buy White Albums, however, embraces an empathetic mission to salvage any record regardless of its condition. In fact, the artist relates that the poorer the condition of the jacket, the more interesting it becomes (Paz 2013). The abjectness of some of the damaged White Albums tests that inclusivity, yet the blemished items harken back to Richard Hamilton’s early ideas in the design process, when he wanted to impart onto the cover either a coffee cup stain or a smear of apple (to commemorate the Beatles’ new Apple imprint). Both were rejected as too difficult to reproduce on a mass scale (Sexton 2017). As it happens, several albums in Chang’s collection do in fact feature coffee spills, cup rings, and food stains. In the end, carelessness and accidents over the decades inadvertently added Hamilton’s abject elements—testing the beholder’s sentiments to either hold onto or cast out the jackets.

Figure 6: Rutherford Chang, We Buy White Albums (2013–ongoing), view of Instagram page. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

The imperfections afflicting the cover occur similarly in the audio. Over the years, nano-imperfections in the manufacturing process build up, records warp, scratches and dirt accumulate, grooves wear down. Chang has overlayed 100 records into four audio files, one for each side of the double album. On side one, the jet engines and first bars of Back in the ussr are recognizable enough, but the listening becomes more difficult as the overlays gradually go out of sync (see Chang n.d. b). Just a few minutes into the album and the songs degenerate into almost indecipherable noise (they are recognizable only because of the uber-familiarity of the melodies). Chang’s overlaying of tracks echoes the studio dubbing techniques utilized by producer George Martin and the Beatles, and recalls the phase shifting of contemporaneous Minimalist composers such as Steve Reich.12I thank Jonathan Goldman for pointing out the connection to Minimalist music. Midway through the compiled album, the distortion exceeds the experiments in noise and feedback found elsewhere in the album in such tracks as Revolution #9 and Helter Skelter.

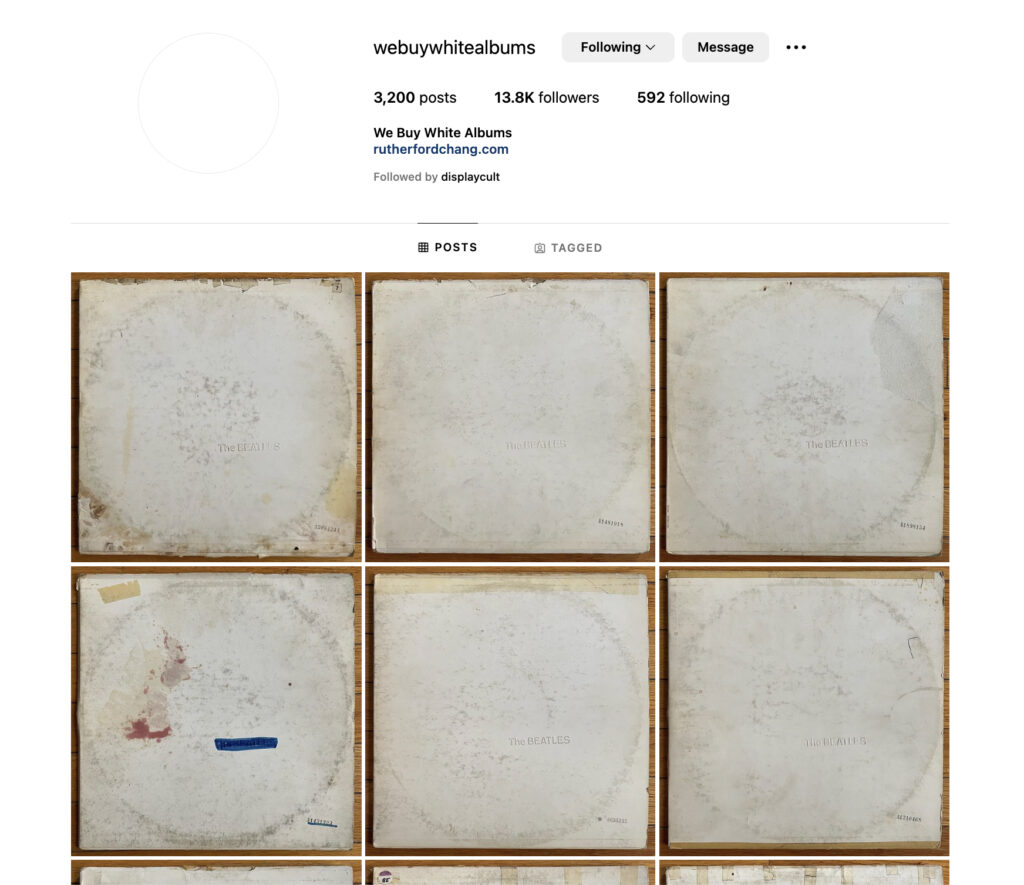

Besides wear and tear, covers were altered by their owners’ pens, markers, and paintbrushes. The unadorned jacket no doubt served as a provocation for writing and artistry: fill me in! The White Album has been claimed to be one of the first instances of postmodernism in popular music, where the songs cohere neither stylistically nor thematically, and thus engage listeners intensely to make sense of the musical diversity.13See Whitley (2000, p. 105) and Littlejohn (2020, p. 89). Such audience activation is visually manifested in the radically distinctive cover, which presented nothing other than the embossed name of the band and a serial number. Rather than interpellating the viewer by a traditional cover—one that illustrates the music and lyrics, contributes a backstory, or provides a supplement that enhances listeners’ understanding of the album—the tabula rasa of the White Album gives no clues as to what might be found within.14Inglis (2001, p. 89). Andrew Goodwin would consider the White Album’s cover to be disjunctive, because it neither illustrated nor amplified the music or the lyrics. Similarly, Nicholas Cook would consider the cover to be contestatory, as it neither conformed to nor complemented the album’s contents (see Belton 2015, p. 4). The meditative blankness may reflect the fact that many of the songs on the album were written in Rishikesh, India, during the time the Beatles studied transcendental meditation at the ashram of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. Judging by the number of the songs on the album that are openly critical of the yogi, the expanse of nothingness may slyly symbolize the benefits (or … Continue reading

The neutral cover eventually served as a raw canvas or sketchpad for the exercise of the owners’ imaginations and agency. Records can be considered a material version of a contact zone between a fan and their favourite rock stars; albums pose as tangible objects that can be personalized to express a fan’s appreciation or dislike (Caillet 2009, p. 4). Such a mass commodity is not just passively consumed but is adapted to the buyer’s personality and integrated into their lives. If the band members seemed like distant celebrities, the markings would bring them closer through hand-made gestures. The cover’s apparent lack of design induced owners to “complete” the task with customized designs (often of a psychedelic variety). Another prompt for intervention relates to the fact that the name of the band and the serial number are rendered askew, giving the cover a subtle imbalance that perhaps unconsciously induced fans to add markings to resolve the unevenness.15An astute member of the audience at the conference “From Record to Art/The Record as Art. Music, Visual Arts, Cinema” (Université de Montréal, May 2022), where a version of this article was presented, observed that Beatles fans may have sensed the imminent break-up of the band evident in the music and so made markings on the blank cover as an effort to keep them together. On the White Album and the band’s dissolution, see Covach (2019) and Kwong (2020). Prefiguring the DIY covers of punk records, the audience engaged in a kind of folk or populist art in which they could graphically interpret the music. From the same object, then, arose multiple and idiosyncratic versions. In concordance with the revolutionary music on the album, the audience messed with the cover in their own disobedient ways.16Cf. Inglis, who claims that “the all-white cover of The Beatles does not invite interpretation, but restricts it” (Inglis 2001, p. 95). My response is that the interpretation of the audience is not necessarily verbal but graphic and tactile: interpretations occur through the activities of drawing, painting, scribbling, doodling, etc. The care devoted to the album also implies degrees of respect or disregard, another affective aspect of interpretation.

Figure 7: Rutherford Chang, We Buy White Albums (2013–ongoing), view of installation at Recess Gallery, New York (2013). Photo: courtesy of the artist.

Even without the temptation of a plain, bare surface, record owners will still appropriate, intervene into, and react against the message of the album cover. Besides identifying marks such as signatures and dedications, Patrice Caillet (2009) discerns five types of fan alterations to record covers:

- those done out of convenience, because the cover is an available writing surface, a notepad for messages;

- marks as a sign of creative activity, which could represent a person’s “artistic awakening” given that these alterations are often done in adolescence;

- fan outpouring of sentiments about the band and its music;

- the cover as a place for self-expression and comments generally;

- jacket doodling done out of boredom.

Caillet’s types of marking were done on standard album covers with photos or other artwork already in place. The five categories reveal different motivations by fans, ranging from intentional to distracted. Many of the same types of markings occur on the White Album, though the blank slate no doubt offered more encouragement.

The album Chang created from his collection overlays 100 covers upon each other.17The overlay method continues for the interior of the jacket, along with the records’ centre labels, though the printed information tends to blacken out most of the limited space. Chang’s album also includes a print of the 100 covers used in the overlay. If not curated artfully enough, the cover would devolve into a solid black or muddy brown. The artist’s selection imparts a surprising miscellany of information that fills the front, back and inside gatefold:

- mold spots, stains, foxing, splits, creases, tears, chafing;

- repairs done with tape;

- owners’ and institution’s names, initials, dates of acquisition;

- price tags and sellers’ annotations, such as from Goodwill;

- scribbling, notes, doodles, peace signs, repetitions of the band’s name;

- drawings in pen, ink, watercolour, and magic marker; images of hearts, lips, and psychedelic designs;

- comments such as “Kiss Me!” or “Love,” plus poetry and handwritten lyrics.

Whether or not Hamilton foresaw the possibility of fans writing and making their own art on his minimalist cover design, Chang’s project forcefully brings out that potential.

The marks are more than just decoration, however. Returning to the postmodern nature of the White Album, the plain cover also engineers a collaborative or distributed authorship between the Beatles and their fans. Music and cultural critics have noted how the Beatles’ eighth album, Sgt. Pepper’s, exemplified the conceptually integrated and unified rock album. The subsequent White Album completely subverted that unified sensibility through fragmentation, bricolage, genre-blending, quotation, and a multitude of musical styles that varied from one track to the next.18See Littlejohn (2020, p. 91), Brusco (2008), Lubell (2020), and Whitley (2000). The album featured a dizzying array of contradictory affects; critic Russell Reising lists the emotional range to encompass “chaos, celebration, dismay, despair, laughing, crying, commitment, irony… rage, spiritual yearning, soothing lullaby, revolutionary zeal, and domestic quietude” (quoted in Lubell 2020, p. 113). Rather than aligning with a coherent musical worldview, listeners had to navigate a complex, paradoxical soundscape with numerous perspectives and disconnected narrative threads. The album’s prefiguring of postmodern techniques thus shifted the listener from a passive consumer to an active agent in determining the meaning and significance of the disparate ensemble of songs, but also in assessing the role of music (and by extension art) in contemporary society.19See Whitley (2000, p. 106), Lubell (2020), and Brusco (2008). Critic John Littlejohn goes so far as to suggest that the Beatles left the record deliberately unfinished, partly to expose the “process of [its] construction” (Littlejohn 2020, p. 93). The vacant cover here thus plays an essential function: it also could be considered “under construction,” that is, strategically left to the purchaser to finish. The result, then, are multiple covers, filled with unique markings and art, with each owner staking out and authoring a different vision of the album.

Regarding Chang’s collecting overall, its singular focus on the White Album disproves traditional theories of collecting that tend to psychologize the activity or base it in trauma or deviancy. For critic Carlo McCormick (2010, p. 81) and others, collecting is a fetishistic pursuit, one based on sublimated promiscuous impulses. Psychologist Werner Muensterberger (1994) argues it is a means of escaping into a private, magical world (see also Katz 2010, p. 65). To Lydia Yee, curator of the Barbican exhibition Magnificent Obsessions, collecting starts in childhood and serves as a “compensation for the lack of material goods” and functions as a “coping mechanism, dispelling childhood anxieties and difficult memories” (Yee 2015, p. 9). Philosopher Jean Baudrillard equates the collector with the narcissist, because they inevitably only collect themselves (Baudrillard 1994, p. 12). While an art project may have its own unconscious or sublimated dimensions, the characteristics mentioned above are mitigated in We Buy White Albums by the artist’s deliberate and knowledgeable mobilization of collecting.

Figures 8-9: Rutherford Chang, We Buy White Albums (2013–ongoing), view of album covers showing painting and doodling. Photos: courtesy of the artist.

In looking at record collecting specifically, however, more complex reasons arise. How does Chang’s collecting match or differ from that of the typical record connoisseur? Media studies scholar Roy Shuker (2004) has outlined a useful series of characteristics about the various psychologies and motivations of record collectors (rendered in italics below),20Shuker’s characteristics were gleaned from interviewing 67 record collectors. Compare this to the analysis of collectors by music studies scholar Will Straw (1997), who divides their personality traits into the categories of hipness, connoisseurship, bohemianism, and adventure. I would aver that all four types can be found in Chang’s practice, though as a conceptual project it exceeds being contained into a specific identity type. and I will comment on how Chang compares:

– Record collectors love music: This is probably true for Chang too, but the White Album was already massively popular, selling more than 50 million albums so far. It is more relevant to view Chang’s project as a meta-level investigation into the love for music generally.

– Record collectors are obsessive-compulsive: The collecting of a single record certainly counts as monomaniacal. For Chang, however, such monomania is strategic, the basis of his project’s methodology.

– Record collectors’ main concerns are accumulation and completionism: A preoccupation with size and order is undoubtedly exhibited in We Buy White Albums. The artist documents, posts, and tallies each acquisition during the collecting process. And with 3 million numbered albums to potentially collect, the completion is theoretically possible, although futility forms a subtext to such a quest.

– Records anchor the collector’s self-definition and identity: Chang does have a story about his interest in records, but more pertinent to consider here is the notion of an artistic branding. We Buy White Albums is one of the longest-running projects of the artist’s career and probably his best known, thus his identity is intertwined with his collection.

– Collectors utilize selectivity and discrimination: This does and does not apply to Chang. Copies of the White Album are bought because they are cheap (under $20), easily available, and can be in any condition (Kozinn 2013). By accepting all covers, Chang enacts a visual version of the Cagean principle that all sounds are interesting. And given the dismal state of some of the jackets, one can infer that the artist not only rescues items from the limbo of others’ collections, but from the garbage bin as well.

– Record collectors count on economic investment: Just about every journalist comments on the value of some copies of the White Album (#1 sold for $790,000). As part of the process, Chang competes with other collectors and keeps every receipt (Yulman 2017, p. 3). While the White Albums Chang purchases are low-cost and not liable to rise much in price, as an entire artwork, We Buy White Albums would have considerable value.

– Collectors seek to establish logic, unity and control in their lives: True to some degree because Chang’s albums are numbered and organized in sequenced bins, but the damage and doodling on the covers convey both multiplicity and chaos.

– Collectors use records as a form of escape or refuge: Since Chang was born long after the album came out, his collecting as a nostalgic escape is unlikely. Yet the owners selling their albums to the artist often mention reflections and anecdotes about their youth. The recurring public exhibition of We Buy White Albums negates the notion of private refuge.

– A collection signals social and cultural capital: As an artist, Chang does trade on the capital of exhibiting and being in the public eye, yet the capital might be lessened by the fact that many of the records he collects are degraded and abject.

– Record collectors engage in self-education and scholarship: Yes, Chang sees the records as cultural artifacts and himself as an anthropologist. He seeks out objects not only for their own sake but for the stories of their journey through time.21See Yulman (2017, p. 2) and Paz (2013). The artist has even discovered a curious gap in the sequence of the edition; for some reason, no records were printed between the numbers 2.7 and 2.8 million, suggesting a production snafu of some sort (Paz 2013).22Another oddity evident in the collection involves the quality of paper (shinier) from pressings in Japan and the superior condition of albums held by Japanese consumers, who seemed to take much better care of their records than American and British counterparts.

Figures 10-11: Rutherford Chang, The Beatles. We Buy White Albums (2013), front and back covers. Photos: courtesy of the artist.

Chang recognizes the weirdness of his hunt for White Albums and is self-reflexive about the obsessiveness that suffuses the project.23Purchasing records to mostly look at, rather than to play, would qualify Chang’s practice as a form of “perverse” collecting, according to performance studies scholar Philip Auslander (2004, p. 153). While I consider the adjective “perverse” a bit strong, to collect albums for their patina is certainly an alternative to conventional record consumption and goes “against the grain” of music industry intentions and traditional buying habits. To shift focus away from his personal identity, the artist uses two strategies. The first involves staging public events in the manner of an “anti-store,” where he will buy, but not sell White Albums (Maly 2013). With a relaxed demeanor, Chang interacts with the audience of art world cognoscenti, record collectors, and everyday passersby. He calls such interactions an important “random variable” (Yulman 2017, p. 1). Besides conversing with the artist, people can peruse the covers, choose records to play, and tell stories about their own copies of the White Album. During this public iteration, Chang admits to being less like a collector and more like the aforementioned anthropologist: gathering information about consumers’ cultural practices and affective attachments to mass produced music. Secondly, the record store format defuses the artist’s individual subjectivity by creating a simulated institution. With a title and neon sign proclaiming “We Buy White Albums,” Chang implies the existence of a collective enterprise set out to procure copies of the record. Such an entity hints at a broader purposiveness than just personal quirkiness. The motivations thus seem less about vanity or compulsion and more about culturally useful goals like research and analysis.

Figures 12-13: Rutherford Chang, We Buy White Albums (2013–ongoing), view of album covers showing psychedelic art and designs. Photos: courtesy of the artist.

We Buy White Albums aligns with a growing genre of artists’ record collections displayed in galleries and museums. For instance, Yoshitomo Nara’s vinyl collection fills a wall with 352 albums that inspired the artist as a youth in rural, postwar Japan, serving as a form of escape and a tool for self-empowerment (Los Angeles County Museum of Art 2021). Sounds of Christmas, by Christian Marclay, annually offers 1,200 Christmas albums as a resource for DJs to sample and improvise. It demonstrates that even the cliched, kitschy genre of seasonal music can generate experimental compositions (New Museum 2000). Theaster Gates’s A Song for Frankie (2017–21) contains an archive of 5,000 records from the late Chicago DJ Frankie Knuckles, which are made available as a resource to scholars, musicians, and the public (Gates 2021). Lastly, Siemon Allen’s Makeba! (2007) features hundreds of albums by the South African singer to chart the distribution of her anti-apartheid message in the international music scene (Anderson Gallery 2010, pp. 34–39). In similar ways to Chang’s project, these artists display their collections in the visual art context of an exhibition. Yet, more than just being objects of aesthetic appreciation, the records are available for various types of interaction, research, performance, and sociocultural analysis. This expanded manner of engagement shifts these collections from art objects to curatorial projects; in other words, the artists are not just collectors but artist-curators.

Why does it matter to frame Chang’s project as the work of an artist-curator? First, curating is the activity that describes his practice. Chang has developed a conceptual premise or theme, enacted a specific methodology of amassing White Albums, and has purposefully selected other artists’ work, namely that of Richard Hamilton and all the anonymous artists who have inscribed and decorated their albums. Chang has arranged the works with a notable display strategy, that of a faux-record store. He has also documented the works in photographs and Instagram, and the album he produced could be characterized as a type of catalogue. However, Chang also defies traditional curating, and this is where the artistic part of the artist-curator emerges. Institutional art curators tend to select professional artists, and the hundreds of unknown doodlers and draftspersons in Chang’s collection betray this principle. Also undermined are the art world’s interests in quality, rarity, discernment, and connoisseurship. We Buy White Albums tosses aside art market considerations of value in favour of accepting all copies, no matter how poorly kept, damaged, abject, or inappropriately customized.

Secondly, and more importantly, identifying Chang as an artist-curator inflects the way the audience approaches and draws significance from his project. We Buy White Albums is best understood not as an expression of the artist’s psyche, biography, or subject position, but as a project that creatively crosses disciplines and sets up a process that hybridizes art, collecting, presentation, and archiving.24Even when the work is not on display, Chang continues collecting and archiving the albums, demonstrating the long-term aspect of the project. The use of “we” in the title disinvests the work from the singularity of the artist and expands it into a collaborative endeavour. It is no coincidence that Chang’s collection first appeared as a street-level storefront, mimicking the layout of a record store, in New York City’s Recess Gallery. People could view the album jackets as both artworks on the wall and records in a bin. Thus, Chang’s curatorial agency shifted the album from being a musical artifact to a platform of expression. Even more mischievous, perhaps, is the installation’s imposition of the shabbier side of commercial exchange in an area gentrified by tony boutiques and blue-chip galleries. We Buy White Albums’ neon sign readily evokes shady capitalism—pawnshops and low-end retailers who advertise “We buy gold” in downtrodden neighbourhoods.25Thank you to Jonathan Goldman for making this connection. “White” replaces “gold,” with the resulting effect that the recycled albums skewer elitist pretensions of the broader SoHo art scene.

While Chang’s project buys White Albums, it does not “buy into” an ideology of whiteness that is such a prominent visual aspect of the cover. The thousands of examples of patina, markings, and damage certainly draw attention to the myriad ways whiteness is a fragile and ephemeral state. But there is another level in which We Buy White Albums interrogates whiteness. Despite the decolonization informing recent museum theory and practice, the aesthetic associations of the colour white with purity, innocence, and neutrality persist in gallery architecture, as does the capacity of whiteness to represent transcendence, dominance, and privilege.26See, e.g., O’Doherty (1986), Dyer (1997) and Filipovic (2014). The art world perpetuates such connotations in the standardized, ubiquitous display format of the white cube gallery. Introducing scuffed and abject White Album jackets into the white cube destabilizes its sacral ambience. Other senses are called forth to challenge not only the predominance of visual pleasure, such as the tactility of abraded surfaces or the smell of decaying paper, but also the assumption of an eternal presence and metaphysical calm that the white cube generally fosters. Contrarily, the degraded albums testify to the vicissitudes of time and the accidents that eventually erode all things, including artworks.

Figure 14: Rutherford Chang, We Buy White Albums (2013–ongoing), street view of installation at Recess Gallery, New York (2013). Photo: courtesy of the artist.

The whiteness prominent in We Buy White Albums likewise highlights the evolving race relations of the music industry. The Beatles achieved success by recording covers of Black soul and blues artists, and thus transformed what was called “race music” into something more palatable for a mainstream white audience. The whiteness of the White Album jacket, then, aptly references the band’s covering (in both senses of the term) of the Black source material.27Historians of the Beatles point out that the group was openly appreciative of the Black artists they covered. They sought permission to use songs, directed fans to the original artists, supported civil rights personally and in their music, and refused to play at segregated venues. See Robertson (2014), Philo (2014) and Spaine (2022). We Buy White Albums does not overtly suggest a position on whether the Beatles’ musical crossovers were acts of homage or appropriation, but the display of thousands of albums in various distressed states calls forth a reckoning in some manner.28The recent discourse on challenging hegemonic whiteness unveils a newfound relevance of We Buy White Albums, even though the origin of the project centred primarily on the iconic popularity of the Beatles (Drobnick 2023). The multitude of weathering, imperfections, and graffiti tarnish the innocence accompanying the albums’ original appearance. The records thus accrue a different impact because they have been repositioned in a new way by Chang. Such a transformation is characteristic of artist-curating. According to art historian David Freedberg, artist-curating is notable because it “charge[s objects] with meanings that had lain dormant[,] waiting … to be awakened under the conditions” of the new presentation (quoted in Green 2018, p. 220).29Artist-curators can be more flexible in re-interpreting objects than institutional or museum curators, who have an obligation to respect the autonomy and original context of the items they exhibit. For more on concept of the artist-curator, see Jeffery (2015), Filipovic (2017) and Green (2018); see also Lind (2012) on the concept of the “curatorial.”

Such a reframing of the White Album by Chang occurs through the process of “care” that is essential to the activity (and etymology) of curating.30On curating and care, see Reckitt (2016) and Krasny and Perry (2023). We Buy White Albums mobilizes care through several types of mindful attention: saving and preserving distressed covers, re-establishing the albums’ production sequence, displaying patina for appreciation and contemplation, respecting the idiosyncratic markings of former owners, and reflecting upon the various qualities of aging, collaborative authorship, and corroded whiteness. Chang’s patient, long-term, conceptually rigorous process could be said to devote more care to the albums than many of the former owners. Yet in assembling such a large collection, the artist-curatorial stance elicits the records’ latent meanings and prompts the consideration of larger issues. The record collection here becomes more than just an accumulation, but a dynamic form of curatorial research encompassing the interrelationships between ownership and music, records and art, and time and materiality.

Bibliography31All hyperlinks were verified on May 23, 2023.

Anderson Gallery (2010), Imaging South Africa. Collection Projects by Siemon Allen, Richmond, VA.

Auslander, Phillip (2004), “Looking at Records”, in Jim Drobnick (ed.), Aural Cultures, Toronto, YYZBOOKS, pp. 150–156.

Baudrillard, Jean (1994), “The System of Collecting”, in John Elsner and Roger Cardinal (eds.), The Cultures of Collecting, London, Reaktion, pp. 7–24.

Beaumont-Thomas, Ben (2016), “Blockbusters. How Rutherford Chang Became the Second-Best Tetris Player in the World”, The Guardian, January 7, www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/jan/07/tetris-rutherford-chang-artist-nintendo-game-boy.

Belton, Robert J. (2015), “The Narrative Potential of Album Covers”, Studies in Visual Arts and Communication, vol. 2, no 2, www.journalonarts.org.

Brusco, Francesco (2008), “The Embarrassment of Abundance. Unity and Fragmentation on the Beatles’ White Album”, Soundscapes, vol. 21 (December), www.icce.rug.nl/~soundscapes/VOLUME21/White_Album.shtml.

Bury, Stephen (2001), Artists’ Multiples. 1935–2000, London, Ashgate.

Caillet, Patrice (ed.) (2009), Discographisme Récréatif/Homemade Record Sleeves, St. Denis, éditions Bricolage/En Marge.

Chang, Rutherford (n.d. a), “We Buy White Albums”, www.instagram.com/webuywhitealbums/?hl=en.

Chang, Rutherford (n.d. b), “We Buy White Albums”, www.rutherfordchang.com/white.html.

Covach, John (2019), “Afterword”, in Mark Osteen (ed.), The Beatles through a Glass Onion. Reconsidering the White Album, Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, pp. 263–269.

Drobnick, Jim (2023), telephone interview with Rutherford Chang, May 19.

Dyer, Richard (1997), White, London and New York, Routledge.

Dyment, Dave, and Gregory Elgstrand (eds.) (2012), One for Me and One to Share. Artists’ Multiples and Editions, Toronto, YYZBOOKS.

Falcone, Jon (2014), “More than Words. Rutherford Chang and the White Album”, Drowned in Sound, https://drownedinsound.com/in_depth/4148137-more-than-words–rutherford-chang-and-the-white-album.

Filipovic, Elena (2014), “The Global White Cube”, OnCurating, April, www.on-curating.org/issue-22-43/the-global-white-cube.html#.ZGJ3KOzMI-Q.

Filipovic, Elena (2017), The Artist as Curator, Milan, Mousse.

Gates, Theaster (2021), “Social Works. The Archives of Frankie Knuckles”, Gagosian Quarterly, Summer, https://gagosian.com/quarterly/2021/06/30/essay-social-works-archives-frankie-knuckles-organized-theaster-gates.

Green, Alison (2018), When Artists Curate. Contemporary Art and the Exhibition as Medium, London, Reaktion.

Harrison, Charles (1991), Essays on Art & Language, Cambridge, ma and London, mit Press.

Inglis, Ian (2001), “‘Nothing You Can See That Isn’t Shown’. The Album Covers of the Beatles”, Popular Music, vol. 20, no 1, pp. 83–97.

Jeffery, Celina (2015), The Artist as Curator, Bristol, Intellect.

Jones, Kevin (2020), “Revolution to Dissolution. ‘The White Album’s’ Techniques, Packaging and Songwriting as a Reflection of the Beatles and Their Influence”, Interdisciplinary Literary Studies, vol. 22, no 1–2, pp. 31–51.

Katz, Mark (2010), “Beware of Gramomania. The Pleasures and Pathologies of Record Collecting”, in Trevor Schoonmaker (ed.), The Record. Contemporary Art and Vinyl, Durham, NC, Nasher Museum of Art, pp. 62–65.

Konik, Adrian and Inge Konik (2013), “The Political Significance of Patina as Materialised Time”, South African Journal of Art History, vol. 28, no 2, pp. 133–155.

Kosofsky Sedgwick, Eve (2003), Touching Feeling. Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity, Durham, NC, Duke University Press.

Kozinn, Allan (2013), “A Plain White Square, and Yet So Fascinating”, The New York Times, February 22, www.thewhitealbumproject.com/articles/a-plain-white-square-and-yet-so-fascinating/.

Krasny, Elke, and Perry, Lara (eds.) (2023), Curating with Care, London and New York, Routledge.

Kwong, Lucas (2020), “The White Album as Neo-Victorian Fiction of Loss”, Interdisciplinary Literary Studies, vol. 22, no 1–2, pp. 52–77.

Lind, Maria (2012), “Performing the Curatorial”, in Maria Lind (ed.), Performing the Curatorial. Within and Beyond Art, Berlin, Sternberg Press, pp. 9–20.

Littlejohn, John (2020), “Sgt. Pepper and the White Album. The Establishment and Dissolution of the Album Form”, Interdisciplinary Literary Studies, vol. 22, no 1–2, pp. 78–96.

Los Angeles County Museum of Art (2021), “Nara’s Record Collection”, https://www.lacma.org/node/39341.

Lubell, Gabriel (2020), “Progressions of Urgency Within and Across the White Album”, Interdisciplinary Literary Studies, vol. 22, no 1–2, pp. 97–117.

Luke, Ben (2018a), “How Paul McCartney helped Richard Hamilton create the Beatles’ iconic White Album”, The Art Newspaper, November 29, www.theartnewspaper.com/2018/11/29/how-paul-mccartney-helped-richard-hamilton-create-the-beatles-iconic-white-album.

Luke, Ben (2018b), “The White Album. How Richard Hamilton Brought Conceptual Art to the Beatles”, Sotheby’s, November 16, www.sothebys.com/en/articles/the-white-album-how-richard-hamilton-brought-conceptual-art-to-the-beatles.

Maly, Tim (2013), “‘We Buy White Albums’. The Unique Decay of Mass-Produced Items”, Wired, February 27, www.wired.com/2013/02/we-buy-white-albums/.

McCormick, Carlo (2010), “Just for the Record. Vinyl Rules”, in Trevor Schoonmaker (ed.), The Record. Contemporary Art and Vinyl, Durham, NC, Nasher Museum of Art, pp. 78–82.

Mehrens, Shawn Avarzed (ed.), (2016), Rutherford Chang. Game Boy Tetris, Tokyo, The Container.

Muensterberger, Werner (1994), Collecting. An Unruly Passion, Princeton, Princeton University Press.

New Museum (2000), “Christian Marclay. The Sounds of Christmas”, https://archive.newmuseum.org/exhibitions/361.

O’Doherty, Brian (1986), Inside the White Cube. The Ideology of the Gallery Space, Santa Monica, Lapis Press.

Paz, Eilon (2013), “Rutherford Chang – New York, NY”, Dust & Grooves, February 15, http://dustandgrooves.com/rutherford-chang-we-buy-white-albums/.

Philo, Simon (2014), British Invasion. The Crosscurrents of Musical Influence, London, Rowman and Littlefield.

Reckitt, Helena (2016), “Support Acts. Curating, Caring and Social Reproduction”, Journal of Curatorial Studies, vol. 5, no 1, pp. 6–30.

Robertson, Karen (2014), “50 Years Ago. The Beatles, Rock and Race in America”, https://origins.osu.edu/milestones/february-2014-50-years-ago-beatles-rock-and-race-america?language_content_entity=en.

Rosenstein, Leon (2009), Antiques. The History of an Idea, Ithaca and London, Cornell University Press.

Sexton, Paul (2017), “The Beatles’ ‘White Album,’ By Design”, udiscovermusic, December 3, www.udiscovermusic.com/stories/the-white-album-by-design/.

Shuker, Roy (2004), “Beyond the ‘High Fidelity’ Stereotype. Defining the (Contemporary) Record”, Popular Music, vol. 23, no 3, pp. 311–330.

Spaine, Les (2022), “The Beatles and Black Music”, www.beatlesstory.com/blog/2022/10/19/bhm-2022-the-beatles-and-black-music/#:~:text=Although%20it%20may%20have%20started,influenced)%20black%20artists%20later%20on.

Staff, Craig (2015), Monochrome. Darkness and Light in Contemporary Art, London and New York, I.B. Tauris.

Stewart, Kathleen (2007), Ordinary Affects, Durham, NC, Duke University Press.

Straw, Will (1997), “Sizing Up Record Collections. Gender and Connoisseurship in Rock Music Culture”, in Sheila Whitely (ed.), Sexing the Groove. Popular Music and Gender, New York, Routledge, pp. 3–16.

Wagner, Karin (2019), “In Good Condition. The Discourse of Patina as Seen in Interactions between Experts and Laymen in the Antiques Trade”, Culture Unbound, vol. 11, no 2, pp. 252–274.

Whitley, Ed (2000), “The Postmodern White Album”, in Ian Inglis (ed.), The Beatles, Popular Music and Society. A Thousand Voices, London, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 105–125.

Womack, Kenneth (2020), “Introduction. The White Album: An Enigma for the Ages,” Interdisciplinary Literary Studies, vol. 22, no 1–2, pp. 1–4.

Yee, Lydia (2015), “The Artist as Collector,” Magnificent Obsessions: The Artist as Collector, London/Munich, Barbican Gallery/Prestel, pp. 9–15.

Yulman, Nick (2017), “Rutherford Chang on the Art of Collection”, Creative Independent, July 7, https://thecreativeindependent.com/people/rutherford-chang-on-the-art-of-collection/.

| RMO_vol.10.1_Drobnick |

Attention : le logiciel Aperçu (preview) ne permet pas la lecture des fichiers sonores intégrés dans les fichiers pdf.

Citation

- Référence papier (pdf)

Jim Drobnick, « Rutherford Chang. The Record Collector as Artist-Curator », Revue musicale OICRM, vol. 10, no 1, 2023, p. 16-35.

- Référence électronique

Jim Drobnick, « Rutherford Chang. The Record Collector as Artist-Curator », Revue musicale OICRM, vol. 10, no 1, 2023, mis en ligne le 12 juin 2023, https://revuemusicaleoicrm.org/rmo-vol10-n1/rutherford-chang/, consulté le…

Author

Jim Drobnick, OCAD University

Jim Drobnick is a curator and Professor at OCAD University, Toronto. He has published on the visual arts, performance, the senses and post-media practices in recent anthologies such as Sound Affects (2023), Olfactory Art and the Political in the Age of Resistance (2021), Food and Museums (2017), L’Art Olfactif Contemporain (2015), The Multisensory Museum (2014), Senses and the City (2011), and Art, History and the Senses (2010). His books include the anthologies Aural Cultures (2004) and The Smell Culture Reader (2006). He is co-editor of the Journal of Curatorial Studies and co-founder of the curatorial collaborative DisplayCult (www.displaycult.com).

Notes

| ↵1 | For more on these works, see Yulman (2017), Beaumont-Thomas (2016) and Mehrens (2016). Chang’s interest in systems and methods of organizing disparate materials also apply to the artifacts of his own life. For instance, he has kept every receipt for over a decade in chronological order and maintains a list of every flight he has taken (Falcone 2014). |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | Cf. Inglis (2001, p. 89) and Womack (2020, p. 2). Inside the album, however, were photographs of the band and a poster that would appeal to the traditional consumer. See Luke (2018a, 2018b) and Jones (2020). |

| ↵3 | See Lubell (2020) and Littlejohn (2020, p. 90). |

| ↵4 | On Rauschenberg, see Staff (2015, pp. 82–84); on Art & Language, see Harrison (1991). |

| ↵5 | While multiples had been produced earlier, the modern notion of the multiple can be traced to Editions MAT (1959) and early 1960s Fluxus productions. See Bury (2001) and Dyment and Elgstrand (2012). |

| ↵6 | Special limited editions are now a common marketing technique in popular music, as is the collaboration with visual artists to design covers. |

| ↵7 | Chang’s collecting vinyl may be seen as a response to lack of physicality with digital forms of music, but as commentators in Paz (2013) point out, vinyl’s decline since the introduction of mp3s and streaming has not been total, for it has resurged several times. |

| ↵8 | Chang in Maly (2013); see also Yulman (2017, p. 1). |

| ↵9 | The frailty of memory is raised by the premise of the Danny Boyle film Yesterday (2019), which imagines a time when the Beatles’ music has been wiped from cultural memory, except for a few individuals. |

| ↵10 | Maly (2013) likens the covers to serving as memento mori. |

| ↵11 | Another project focusing on the build-up of patina is Christian Marclay’s Record Without a Cover (1985), which involved a series of vinyl LPs released without packaging. The resulting scrapes and scratches from shipping and handling are intentional and integral to the work. |

| ↵12 | I thank Jonathan Goldman for pointing out the connection to Minimalist music. |

| ↵13 | See Whitley (2000, p. 105) and Littlejohn (2020, p. 89). |

| ↵14 | Inglis (2001, p. 89). Andrew Goodwin would consider the White Album’s cover to be disjunctive, because it neither illustrated nor amplified the music or the lyrics. Similarly, Nicholas Cook would consider the cover to be contestatory, as it neither conformed to nor complemented the album’s contents (see Belton 2015, p. 4). The meditative blankness may reflect the fact that many of the songs on the album were written in Rishikesh, India, during the time the Beatles studied transcendental meditation at the ashram of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. Judging by the number of the songs on the album that are openly critical of the yogi, the expanse of nothingness may slyly symbolize the benefits (or lack of) they received. |

| ↵15 | An astute member of the audience at the conference “From Record to Art/The Record as Art. Music, Visual Arts, Cinema” (Université de Montréal, May 2022), where a version of this article was presented, observed that Beatles fans may have sensed the imminent break-up of the band evident in the music and so made markings on the blank cover as an effort to keep them together. On the White Album and the band’s dissolution, see Covach (2019) and Kwong (2020). |

| ↵16 | Cf. Inglis, who claims that “the all-white cover of The Beatles does not invite interpretation, but restricts it” (Inglis 2001, p. 95). My response is that the interpretation of the audience is not necessarily verbal but graphic and tactile: interpretations occur through the activities of drawing, painting, scribbling, doodling, etc. The care devoted to the album also implies degrees of respect or disregard, another affective aspect of interpretation. |

| ↵17 | The overlay method continues for the interior of the jacket, along with the records’ centre labels, though the printed information tends to blacken out most of the limited space. Chang’s album also includes a print of the 100 covers used in the overlay. |

| ↵18 | See Littlejohn (2020, p. 91), Brusco (2008), Lubell (2020), and Whitley (2000). |

| ↵19 | See Whitley (2000, p. 106), Lubell (2020), and Brusco (2008). |

| ↵20 | Shuker’s characteristics were gleaned from interviewing 67 record collectors. Compare this to the analysis of collectors by music studies scholar Will Straw (1997), who divides their personality traits into the categories of hipness, connoisseurship, bohemianism, and adventure. I would aver that all four types can be found in Chang’s practice, though as a conceptual project it exceeds being contained into a specific identity type. |

| ↵21 | See Yulman (2017, p. 2) and Paz (2013). |

| ↵22 | Another oddity evident in the collection involves the quality of paper (shinier) from pressings in Japan and the superior condition of albums held by Japanese consumers, who seemed to take much better care of their records than American and British counterparts. |

| ↵23 | Purchasing records to mostly look at, rather than to play, would qualify Chang’s practice as a form of “perverse” collecting, according to performance studies scholar Philip Auslander (2004, p. 153). While I consider the adjective “perverse” a bit strong, to collect albums for their patina is certainly an alternative to conventional record consumption and goes “against the grain” of music industry intentions and traditional buying habits. |

| ↵24 | Even when the work is not on display, Chang continues collecting and archiving the albums, demonstrating the long-term aspect of the project. |

| ↵25 | Thank you to Jonathan Goldman for making this connection. |

| ↵26 | See, e.g., O’Doherty (1986), Dyer (1997) and Filipovic (2014). |

| ↵27 | Historians of the Beatles point out that the group was openly appreciative of the Black artists they covered. They sought permission to use songs, directed fans to the original artists, supported civil rights personally and in their music, and refused to play at segregated venues. See Robertson (2014), Philo (2014) and Spaine (2022). |

| ↵28 | The recent discourse on challenging hegemonic whiteness unveils a newfound relevance of We Buy White Albums, even though the origin of the project centred primarily on the iconic popularity of the Beatles (Drobnick 2023). |

| ↵29 | Artist-curators can be more flexible in re-interpreting objects than institutional or museum curators, who have an obligation to respect the autonomy and original context of the items they exhibit. For more on concept of the artist-curator, see Jeffery (2015), Filipovic (2017) and Green (2018); see also Lind (2012) on the concept of the “curatorial.” |

| ↵30 | On curating and care, see Reckitt (2016) and Krasny and Perry (2023). |

| ↵31 | All hyperlinks were verified on May 23, 2023. |