Locked Grooves, a Circle of Hands.

Paranormal Affects in Georgina Starr’s I am the Medium

Jennifer Fisher

| PDF | CITATION | AUTHOR |

Abstract

This article examines the complex affects of I am the Medium, a vinyl record artwork and sound installation produced by Georgina Starr, a London-based visual artist affiliated with the second wave of Young British Artists (YBAs). This project was exhibited at the Le Confort Moderne in Poitiers, France in 2010. Starr’s limited-edition LP features recordings made during séances in which she participated over the period of a year. Formally, the record is extraordinary in that it is structured in the form of locked grooves, rather than the spiral continuum of conventional vinyl recordings. Each discrete track consists of a 1.8 second phrase that repeats, creating a mantra-like incantation that resonates in the gallery atmosphere. Much in the same way that sound vibrations are captured and replayed on vinyl records, the etheric signatures of spirit entities manifest through mediumistic channeling. Issues of mediumship raised by this work will be situated in relation to Starr’s sound oeuvre, particularly her projects that have deployed paranormal methodologies.

Keywords: artist’s records; locked grooves; paranormal affect; Spiritualism; Georgina Starr.

Résumé

Cet article examine les affects complexes de I am the Medium, une œuvre d’art et installation sonore sur disque vinyle produite par Georgina Starr, une artiste visuelle londonienne affiliée à la deuxième vague des Young British Artists (YBAs). Ce projet a été exposé au Confort Moderne de Poitiers, en France, en 2010. Le disque en édition limitée de Starr présente des enregistrements réalisés lors de séances auxquelles elle a participé pendant un an. Sur le plan formel, le disque est extraordinaire en ce sens qu’il est structuré sous la forme de sillons fermés, plutôt que sous la forme du continuum en spirale des enregistrements vinyles conventionnels. Chaque piste distincte consiste en une phrase de 1,8 secondes qui se répète, créant une incantation semblable à un mantra qui résonne dans l’atmosphère de la galerie. De la même manière que les vibrations sonores sont capturées et rejouées sur des disques vinyles, les signatures éthériques des entités spirituelles se manifestent par la canalisation médiumnique. Les questions de médiumnité soulevées par cette œuvre seront mises en relation avec l’œuvre sonore de Starr, en particulier ses projets qui ont usé de méthodologies paranormales.

Mots clés : disques d’art ; affect paranormal ; sillons fermés ; spiritisme ; Georgina Starr.

Figure 1: Georgina Starr, The Voices of Quarantaine (Part 1) (2021), performance lecture, video, 30 minutes. Photo: courtesy of the artist and Film and Video Umbrella, London.

Georgina Starr’s installations situate viewers in intimate liminal encounters that interrogate the cultural politics of listening to pose innovative esoteric and affective relationships. Her audio artworks compellingly investigate the vinyl LP format as an artistic medium. London-based and affiliated with the second wave of Young British Artists (aka YBAs), she has, over the last 20 years, explored invisible, lost or fragile phenomena (Sorrell-Hayashi 2008). As a collector of found sounds in the ethnographic sense, her oeuvre has deployed field recordings of normally neglected speech assembled from unusual contexts. Likewise, Starr’s work explores making personal acts public, often those that involve relational interactions (Reitmeier 1996, p. 15), such as taping private conversations the artist overheard in a mall. Her work has also probed the affordances of media of communication such as the telephone or television to operate as portals between material and immaterial worlds, as well the phenomena of “hearing voices.”1The Hearing Voices Network is a London-based organization that advocates to create respectful and empowering support for people to talk freely about voice-hearing, visions, and similar sensory experiences.

Several of the artist’s recent projects combine sound recordings with atmospheric settings to investigate acoustic phenomena involved with the communication of messages from immaterial places. These projects are described by the artist in her performative-lecture, The Voices of Quarantaine (Part 1) (2021).2The Voices of Quarantaine (Part 1) by Georgina Starr was commissioned by Glasgow International 2021 and Film & Video Umbrella, London. Starr drew the film’s title from Celtic mythology where une quarantaine marks a 40-day liminal and precarious period following the first full moon in spring where the normal boundaries between the Earthly world and that of Spirit dissolve, and spirits can commune with humans (Pinksummer 2022). Created during 2019 and early 2020, prior to the coronavirus shutdowns, the project presciently anticipated the conditions of forced isolation induced by the pandemic. The video begins by showing the artist seated with a record turntable on her right, flowers on her left, directly addressing the viewer. At one point, she relates that as a six-year-old child she had been awakened at night by the sound of a cascading chorus of female voices. These haunting intonations drew her to experiences of somnambulism—a state of waking-sleep. She once awoke to find that she had sleepwalked into her parents’ bedroom. A doctor diagnosed her experience of these etheric utterances as “auditory hallucinations,” explaining that this phenomenon was due to a specific stage of brain growth, and would be remedied by a normal developmental process of “synaptic pruning.” Starr goes on to share that during these episodes, she experienced her brain as operating like an antenna or transmission aerial that could receive information from another place in the form of cryptic messages she could not quite understand. Starr’s experience with uncommon auditory perception underscored her artistic conviction that the materiality of her brain was somehow attracting female voices from the cosmos (Starr 2021). At another point in the lecture, Starr plays a highly-granular sounding 12” vinyl LP that delves into recovering the maternal voice. This record work, entitled Mum Sings Hello (1992),3Mum Sings Hello (1992) was featured in Georgina Starr’s exhibition, I am a Record (2009). captures the statically-textured sounds of Starr’s mother, Christina, singing the popular 1984 Lionel Ritchie ballad, “Hello.” Recorded on a telephone answering machine and degraded through generations of dubbing, the tune and timbre are barely discernable, to the point where any maternal presence is rendered ethereal (Paterson 2023). The distorted ballad materializes as if transmitted over a vast expanse, related to the artist’s meditation on the collateral damage of her mother’s struggles with depression (Paterson 2017, p. 47).

Figure 2: Georgina Starr, Quarantaine (2020), film, 43 minutes. Photo: courtesy of the artist, Film and Video Umbrella, London, The Hunterian, Glasgow, Glasgow International 2021, and The Art Fund Moving Image Fund.

Raised as a Catholic, Starr’s fascination with the corporeal, the spectral, and the incantatory is evident in her lecture, which proposed the aesthetic implications of being auditorily impregnated by “the holy ghost.”4Another artwork that makes visible the sound of immaculate conception is the inscription of divine vocalization as an arc of golden words connecting the angel Gabriel and the Virgin Mary in Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi’s elegant 1333 painting the Annunciation with St. Margaret and St. Ansanus, at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. Starr constructed a monumental model of her mother’s ear as a portal connecting the tangible and intangible worlds. She asked: what might non-physical immaculate conception sound like? Once again drawing on childhood memory, Starr recalled the eerie resonances of telephone wires of her street in Leeds, which emitted audible fragments of conversations, particularly the familiar telephonic greeting, “hello,” that reiterated with the frequency of a chant, a kind of rosary of “hellos.” Quarantaine involved other female performers in a kind of transcendental choreography designed by the artist to unleash inhibiting energies from their bodies. Accompanied by celestial voices, the auditory combined with kinaesthetic release. Her lecture concluded with the artist slithering into the gigantic form of the motherly ear, thus marking a return and inhabitation of mother consciousness.

Figure 3: Georgina Starr, The Voices of Georgina (1993), 12” vinyl with hand-made cover artwork from I am a Record, vinyl archive (2010). Photo: courtesy of the artist.

The use of sound to bridge different states of being continues with Starr’s experiments in paranormal methodologies, which are longstanding in her work. Fifteen years prior to I am the Medium, her conceptual artwork Getting to Know You (1995) was premised as an experiment to see what she could discern about someone she had never met using the technologies of different psychic phenomena.5My anthology, Technologies of Intuition, explores intuition contingent to processes of “coming to know” involving a range of technologies—psychometry, aura photography, mediumship, meditation, Tarot—that have been used by artists (Fisher 2006). During a residency in Amsterdam at the Rijksakademie, Starr requested to be given a list of 15 people willing to respond to her requests without meeting in person or directly interacting. From those who responded, she chose an individual with the initials “GS.” She proceeded to have GS’s palm print read, their handwriting analyzed, the numerology of their date of birth calculated, their dreams scrutinized, their tea leaves interpreted, and so on. The readings revealed an intimate portrait of GS, even noting the “double life” of this person. Starr subsequently learned that GS was in fact a well-known Dutch author who writes under a pseudonym, and thereby occupied two identities simultaneously. Ultimately, the insights generated through the paranormal research on her unknown collaborator ended up being revelatory to both the artist and writer.

Figure 4: Georgina Starr, I am a Record (2010), installation with 80 vinyl records and listening booths. Photo: courtesy of the artist and Le Confort Moderne.

In the context of the artist’s ongoing aesthetic explorations of sound and consciousness, I will now turn to Starr’s audio installation, I am the Medium, which configures the record apparatus to interpolate gallery viewers within complex multisensory affects. Its first iteration was featured in Starr’s 2010 career retrospective I am a Record, exhibited at Le Confort Moderne in Poitiers, France. The exhibition encompassed 20 years of Starr’s sound-based works including conversations, field recordings, and soundtracks on vinyl LPs. Each playable LP artwork was displayed within a custom-made listening booth, designed to sonically engage viewers playing the record in person. These interactive sound stations have become a distinctive trope of the artist’s oeuvre. Significantly, several works featured Starr’s recordings of sessions with psychic mediums. Initially a professed “nonbeliever,” Starr attributes her interest in mediumship to her friendship with the late English artist and Spiritualist, Ronaldo Wright, with whom she had collaborated to create portraits inspired by Hollywood movie stars that featured Starr in glamorous poses (Fisher 2022). At Wright’s invitation, the artist attended a séance at the Spiritualist Society in London at 12 Belgrave Square. Starr had become intrigued with Wright’s involvement with spirit communication, particularly his production of several channeled books that he claimed were co-authored by a spirit entity while he was in trance. The entity, “Hafed”—declaring himself to be one of the Magi of Biblical renown—describes what life is like in spirit and chronicles the missing years of Jesus Christ.6In the introduction, Ronaldo Wright describes how the book marks a continuation of the original nineteenth-century Spiritualist investigations of David Durguid, a famous Glasgow medium who authored the best-selling book Hafed, a Prince of Persia at the request of Spirit. Inspired to explore the phenomenon of mediumship further, Starr framed her psychic research in the form of a conceptual artwork. The premise for the piece was that she would commit to being read by twelve mediums, one a month, for a year, and record the sessions. Subsequent to her reading at the Spiritualist Society, Starr began to visit a wide range of psychics using varying approaches. One of the artist’s more unlikely psychic readings took place at Selfridges, a high-end London department store. The session was situated in the cosmetics department in a purple velvet enclosure that resembled a changing room. Reflecting on this strange conjunction of channelling spirit while shoppers browsed nearby, Starr related that she felt she had fallen into a fringe reality and only persisted with the reading to fulfill her commitment to the artwork (Fisher 2022; Walsh 2020).

Several aspects of I am the Medium contribute to understanding the record as an art form within the context of contemporary art. Notably, Starr’s record is formally unusual in that it features what are termed “locked grooves” rather than the spiral continuum of conventional recordings. Typically, locked grooves are inscribed at the end of the side of the vinyl disc, so the stylus will circle indefinitely until it is stopped. Starr’s intervention into the record apparatus strategically deploys the repetition of the locked groove as a formal aesthetic device.7The formal logics of the locked groove have been explored in LP recordings by artists such as Christian Marclay, whose Groove (1997) side B includes six locked-groove pieces. Similarly, the Beatles, likely inspired by musique concrete, inserted a locked-groove voice segment at the end of a side on the mono uk Parlophone edition of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967) that gave the option of being played either forward or backward. Each locked groove comprises a discrete soundtrack consisting of a 1.8 second segment from a mediumship session (a voice or sometimes an ambient sound from its space), that repeats to create a mantra-like recitation. Expanding upon the convention of the fixed vinyl track, Starr’s 12” vinyl LP, I am the Medium, structures 250 locked grooves, each capturing an energetically-charged moment from sessions channeling the spirit world. Each locked groove enacts an affective signature—whether the tone of a voice, the resonance of a room, the intensity of an atmosphere—of sound sampled from one of the artist’s 12 readings with psychic mediums.

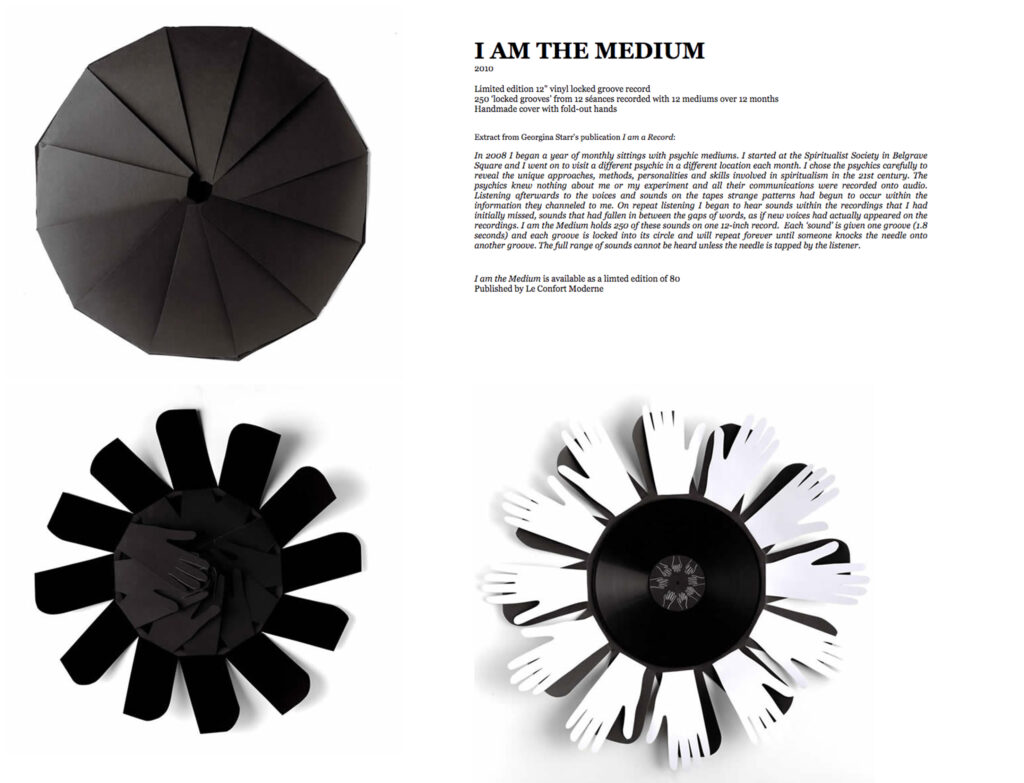

Figure 5: Georgina Starr, I am the Medium (2010), 12” locked groove vinyl edition with fold-out hands artwork. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

Many of the locked grooves transmit a unique tenor of the mediumistic performances to convey a wide range of emotion and mood. The tone of the mediums can be exclamatory when attempting to bring forth a name: “Elizabeth!” “John!” “Tom or Thomas!” Or inquisitive: “Who’s David?” They can relate the delight of recognizing a loved one: “Daddy!” At the same time, they can declare presences encountered during the channeling process: “An Edward is coming,” or “The name James comes to me.” Some utterances suggest the proprioceptive mode of psychic perception noting “tingling sensations.” Others express the medium’s personal response to a specific spirit entity: “He’s nice actually.” Yet others empathetically sense emotion, such as feeling a sense of sadness while “looking into her eyes.” Still others pointedly address the client: “You’re definitely very psychic!” or “You’re going to Paris,” or “It’s like Spirit brought you.” The readings also recount a panorama of objects perceived during channeling: “a suitcase,” “a boat,” or “a washing machine.” Likewise, every locked groove sampled from the reading sessions transmits aspects of duration within the reading as the medium adapts to the inflow of information, which can often come through quite rapidly. The voice can stop and start, become “affected” to speak with a foreign accent, or adopt a standpoint strikingly different from that of the medium’s evident personality.

While at first Starr attended to the narrative content of discursive speech that conveyed the psychic predictions for her life, she found with repeated listenings that non-discursive sounds in the gaps between the vocal utterances became equally important. The 1.8 second samples include an intriguing range of ambient sounds that suggest spirit activity, like a breath or a creak in the background. These reverberations recall the sonic affects of the séance: knocking… rapping… humming HVAC… thudding. Also audible are samples of affect-conveying, phatic utterances in the form of coughs, ums, moans… or laughter. These noises operate as shifters that take the ear into atmospheric space beyond spoken language. When the record is played in the gallery, each locked groove pulses indefinitely until the stylus is tapped by a listener. The rhythmic regularity of each track produces an absorbing and mesmerizing sonic ambience that, in the gallery context, reverberates a hypnotic, otherworldly, and even hallucinatory effect.8Richard Dyer (1992) has described the capacity of rhythm to convey non-representational affect.

In its form as an art multiple in a limited edition of 80, I am the Medium combines a vinyl LP with an elaborate sleeve to articulate an artwork that unites the record medium and its status as art object. The album sleeve is hand-folded by the artist to comprise a 12-sided dodecagon of hands that quite literally “hold” the vinyl. When closed, the matte black album cover resembles a camera shutter pleated around the vinyl disc in a haptic grasp. In the same way that a camera shutter opens to expose the film, the sleeve unfurls to reveal, pop-up style, a circle of twelve silhouetted hands, each reaching outward. On the record’s label, another circuit of eight smaller hands faces inward towards the middle of the disc. These circuits of hands reference a key performative convention of the Spiritualist séance. Staged in the round, the grasped hands of participants are believed to create an energetic current that facilitates the channeling of spirit entities. In its formal logic, the album cover both protects the album and evokes the performance of mediumship.9The hand motif has persisted in Starr’s work, and appears in a Tarot deck she has been working on since 2013, the paintings for which are currently on exhibition at Pinksummer Contemporary Art in Genova, Italy.

While I am the Medium operates as a limited-edition LP soundwork, it has also been realized in the form of a gallery installation, as staged at Le Confort Moderne in Poitiers. Here, the beholder enters a dark space to find the vinyl record on the turntable below a parabolic speaker. The lighting directs attention to the turntable, while illuminating viewers who might be engaging with the piece. Recalling the mood of a séance, the murky light obscures the walls of the room, conveying a mood of intimate obscurity. Where the locked-groove messages carry the capacity to repeat infinitely in the space, gallery visitors can choose to sustain one assertion, or sample a selection. The beholder is lured to tap the stylus with their hand in order to navigate the 250 locked grooves, without knowing where it will land as it skids across the album’s surface. In this way, I am the Medium simultaneously engages listening, touch, and a kind of aleatory engagement.

Starr’s formulation of mediumship in I am the Medium raises the question of just what, in fact, constitutes the “medium” of this artwork. In the most rudimentary sense, the vinyl imprint comprises the communication medium through which resonance is conveyed. Given that sound requires a medium to be transmitted, Starr’s declaration, “I am the medium,” simultaneously asserts her identification with the sound encoded on the LP recording, on the one hand, and her identification with the agency of Spiritualist channeling, on the other.10Georgina Starr staged herself as a medium on the poster for her 2012 performance, THEDA. There has been a long history of artists scrutinizing the role of spirit mediumship. For example, in 1957, the renowned French conceptualist Marcel Duchamp referenced Spiritualist channeling in his description of the attributes of creative agency when he proclaimed: “[T]he artist acts like a mediumistic being who, from the labyrinth beyond time and space, seeks his way out to a clearing” (Duchamp 1957, p. 138). With this statement, Duchamp asserts the centrality of intuition to navigating artistic execution while affirming that the imaginative locus of art’s creation exceeds temporal and spatial limitations.

But whether enacted psychically or artistically, the visionary capacity of mediumship is not unbiased. Considering the medium to be a conduit of communication, Marshall McLuhan’s 1964 adage “the medium is the message”—that is, that each medium of communication creates its own context of meaning—becomes applicable not only to the record as a medium of communication, but also to the discursive contexts governing mediumistic spirit communication. Rather than being transparent communicators, Spiritualist mediums carry the bias of their lived social, cultural, and political context. As each psychic uses their body, cognition, ethics, and intellect in the performance of their gifts, their cultural formation and personality will inevitably determine what they are able to receive and convey. Yet, the identities of channelled spirits can also defy gendered, ethnic, or cultural essentialism, and show up through a surprising range of mediating bodies. Some representations of mediumship in popular film support spirit agency as non-essentialist. For example, in the romantic comedy Ghost (1990), Whoopi Goldberg plays an African American medium, Oda Mae Brown, who channels the recently departed spirit of a white man, Sam Wheat (Patrick Swayze), effecting an unusual love triangle with his grieving partner Molly Jensen (Demi Moore). In one scene, Goldberg, while in trance, mediumistically becomes Swayze, who then shares an intimate embrace with Moore. While spiritually the Ghost narrative supports a reunion of lovers, physically the contact requires a same-sex, biracial kiss. This performance of mediumship, likewise, supports compelling varieties of intersubjective, transpersonal conjunctions. Such a blurring of discrete subjectivities, in turn, troubles the notion of visionary capacity premised on the uniqueness and autonomy of an individual.

There is therefore a compelling extra-discursive and trans-corporeal freedom suggested by the idea of spirit communication.11Toronto psychic medium Brough Perkins has assured me that spirits only show up when they want to show up, and therefore channeling does not involve the troubling ethics of “waking up” the deceased. Indeed, Starr’s 2007 film, THEDA, performatively channels the artist’s reimaginings as lost movies by the silent film star Theda Bara. The poster depicts the artist enacting Theda in the role of a psychic medium at a séance.12Starr’s enactment of the figure of Theda Bara was prompted by her mother Christine’s resemblance to the silent movie star. In our conversation, Starr related her interest in the foundational conditions of early Spiritualism as an emancipatory platform for women (Fisher 2022). During the nineteenth century, Spiritualist mediums channeling voices that were not their own commanded large audiences. At a time when women were denied basic human rights and the ability vote, female spirit mediums assumed agency, influence, and the power of knowledge production as they channeled messages from spirit entities in the public sphere. Nineteenth-century Spiritualism became closely affiliated with important freedom movements including suffrage and the abolition of slavery (Braude 1989). Starr’s work sustains a liberatory feminism in highlighting women performers, imaging women’s self-empowerment, and acknowledging the importance of female friendship.

Figure 6: Georgina Starr, THEDA (2007), film poster. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

In the current era, the emancipatory promise of mediumship is reviving, sparking a paranormal turn in the art world signaled by the 2018–2019 exhibition by the Swedish medium-artist Hilma Af Klint at the Guggenehim Museum, New York, which garnered the largest attendance in the history of the museum. Starr’s esoteric inquiries align with the intersectionality of fourth-wave feminism, where conceptions of what constitutes knowledge have become more porous and open to preternatural methodologies.13Like Starr, esoteric modes have informed the oeuvre of a range of feminist artists including Chrysanne Stathacos and Karen Finley who have used paranormal methods and agencies to generate work that participates in etheric communication. See Fisher (2006). One key task of fourth-wave feminism is to rethink the psychic, somatic, and affective significance of the senses, experience, and intuition related to ways and processes of coming to know (Blackman 2019; Brennan 2004; Trinh 1991; Buck-Morss 2002). Given such esoteric epistemologies, the political issue becomes: Whose knowledge counts? Increasingly, the epistemological stakes informing the production of knowledge in art encompasses the fusing of social justice initiatives with the participation of spirit entities.

At the same time, an emancipatory moment involving objects considered to be sacred by their originating cultures is underway in art institutions. The current climate of decolonization challenges museum curators to reconcile conceptions that Indigenous and African artifacts, for example, are considered spiritually sentient by their communities. Coming to light through decolonial perspectives is the unfortunate fact that such holdings are in fact incarcerated in museums. As Indigenous scholar Dylan Robinson has argued, for Indigenous people, museum visits with ancestral objects displayed in vitrines feels like visiting a relative behind glass in prison. Acknowledging this carcerial relationship with objects considered by their communities to be living ancestors confined in glass vitrines raises pressing questions surrounding museological conservation and exhibition practices (Robinson 2020). This perception corresponds to a shift in understanding that spiritually resonant artifacts are, in fact, not objects at all but living entities with which Indigenous communities share intimate kinship. The current decolonization underway in museums widens the epistemological frame to reconsider consciousness not only in the rehabilitation of museological practices, but also to encompass formerly marginal and even paranormal modes of knowledge production.

Figure 7: Georgina Starr, I am the Medium (2010), installation with 12” locked groove vinyl, turntable, spotlight and parabolic speaker. Photo: courtesy of the artist and Le Confort Moderne.

Just as Starr’s inflection of mediumship encourages tangible contact with spirit, the context where psychic readings are performed generates a palpable atmosphere. The medium performs the sensory labour of attending to the energies of spirit coming through, holding space for the channel to open and conveying relevant messages to the person read.14Affect theorist Kathleen Stewart suggests that “Atmospheres have gradients, valences, moods, sensations, tempos, and lifespans. An atmospheric fill resonates between the material and the potential” (2010, p. 8). In a similar way, enactments of mediumship, in effect, “perform affect” in Kathleen Stewart’s terms of “an atmospheric attunement … an alerted sense that something is happening … an attachment to sensing out whatever it is.” I would suggest, then, that the atmospheric attunements of I am a Medium engage sonic affect in the activation of intuition. Starr’s work presents psychic reading as a dynamic energetic exchange between the reader, the subject, and the spirits who arrive as the medium transmits messages and affects to “both generate and arrange knowledge” in Stewart’s sense (2010, p. 4). When activated by the viewer, Starr’s I am the Medium simultaneously frames the relational conjuncture of the imprinted record, its sound output, and the feeling of gallery space.

It is these elements of interstitial ambience that combine in the aural impact and atmospheric force field comprising this work. Attending to the mysterious auditory impressions of the “in-between” encounter gives way to free-floating affects: Do they belong to the work? To the artist? To the psychic or to the beholder? Starr related to me that people sometimes hear their own names in the recording or cast the needle on the record’s surface in an aleatory manner to receive what they feel is a spirit message for them (Fisher, 2022). There is a chance quality to such engagement: where the process of selecting messages expands the agency of viewers as they become interpellated. It is in this sense that the sonic field produced by this record artwork assumes in itself the capacity of a divinatory medium.

Bibliography

Bashkoff, Tracey (2018), Hilma af Klint. Paintings for the Future, New York, Guggenheim Museum.

Blackman, Lisa (2019), Haunted Data. Affect, Transmedia and Weird Science, London, Bloomsbury Academic.

Braude, Anne (1989), Radical Spirits. Spiritualism and Women’s Rights in Nineteenth-Century America, Boston, Beacon Press.

Brennan, Teresa (2004), The Transmission of Affect, Ithaca, Cornell University Press.

Buck-Morss, Susan (2002), “Aesthetics and Anaesthetics. Walter Benjamin’s Artwork Essay Reconsidered”, October, vol. 62, pp. 3–41, https://doi.org/10.2307/778700.

Colbert, Charles (2002), “A Critical Medium. James Jackson Jarves’s Vision of Art History”, American Art, vol. 16, no 1, pp. 20, 22.

Deleuze, Gilles (1989), Cinema 2. The Time Image, trans. by Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, pp. 98–111.

Drobnick, Jim (2016), “Installation Art. The Predicament of the Senses”, catalogue essay for Installations. À la Croisée des Chemins/Installations. At the Crossroads, curated by Bernard Lamarche, Quebec City, Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec (English and French), pp. 128–138, 196–205.

Duchamp, Marcel (1957), “The Creative Act”, paper presented at the Convention of the American Federation of Arts, Houston, Texas. Later published in The Essential Writings of Marcel Duchamp (1975), ed. by Michel Sanouillet & Elmer Peterson, London, Thames and Hudson, pp. 138–140.

Durant, Mark Alice, and Jane D. Marsching (2005), The Blur of the Otherwoldly. Contemporary Art, Technology and the Paranormal, Baltimore, Center for Art and Visual Culture, University of Maryland.

Dyer, Richard (1992), “Entertainment and Utopia”, Only Entertainment, London & New York, Routledge, pp. 18–44.

Fisher, Jennifer (2006), Technologies of Intuition, Toronto, YYZBOOKS, Winnipeg, MAWA.

Fisher, Jennifer (2013), “Paranormal Art History. Psychometry and the Afterlife of Objects,” in Olu Jenzen and Sally R. Munt (eds.), The Ashgate Research Companion to Paranormal Cultures, Surry, Ashgate, p. 311–327.

Fisher, Jennifer (2022), interview with Georgina Starr, April 21.

Gavin, Francesca (2022), “Georgina Starr”, Twin Magazine, no 26, https://georginastarr.com/documents/Georgina-Starr-Twin-Magazine-Story_2022_000.pdf, accessed May 12, 2023.

Kosofsky Sedgwick, Eve (2003), Touching Feeling. Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity, Durham, nc and London, Duke University Press.

Marclay, Christian ([1982]1997), Groove, New York, The Vinyl Factory, edition of 300.

McGarry, Molly (2008), Ghosts of Futures Past. Spiritualism and the Cultural Politics of Nineteenth-Century America, Berkeley, University of California Press.

McLuhan, Marshall (1964), Understanding Media. The Extensions of Man, Toronto, McGraw-Hill.

McMullin, Stan (2004), Anatomy of a Séance. A History of Spirit Communication in Central Canada, Montreal, Kingston, London & Ithaca, McGill-Queen’s Press.

Oursler, Tony (2019), “Notes on Mysticism and Visual Transects”, in Shannon Taggart (ed.), Séance, Somerset, Fulgur Press, pp. 10–27.

Paterson, Dominic (2020), “Quarantaine. Taking Possession in Three Acts,” Film and Video Umbrella (FVU), www.fvu.co.uk/read/writing/quarantaine-taking-possession-in-three-acts, accessed May 9, 2023.

Paterson, Dominic (2017), “‘Making up Mothers’. Georgina Starr’s Channelling of the Maternal,” Performance Research, vol. 22, no 4, pp. 44–52.

Pinksummer Contemporary Art (2022), Georgina Starr-Quarantaine, press release for a solo exhibition at Pinksummer Contemporary Art, Genova, Italy, May 2–September 17, www.pinksummer.com/en/georgina-starr-quarantaine/, accessed May 26, 2023.

Reitmeier, Heidi (1996), “Things You Always Wanted to Do But Were Afraid To” (interview with Georgina Starr), Women’s Art Magazine, January–February, pp. 12–15.

Robinson, Dylan (2020), Hungry Listening. Resonant Theory for Indigenous Sound Studies, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press.

Sconce, Jeffrey (2000), Haunted Media. Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television, Durham & London, Duke University Press.

Sorrell-Hayashi, Poppy (2008), “Georgina Starr. Interview”, Supersweet, http://supersweet.org/main.aspx?atype=1&aname=Art_Georgina_Starr&con=1&sc1=0&sc2=0, Accessed May 26, 2023.

Starr, Georgina (n.d.), Official Website, www.georginastarr.com, accessed May 26, 2023.

Starr, Georgina (2021), “Voices of Quarantaine (Part 1)”, lecture co-commissioned in 2019 by the Hunterian, University of Glasgow and the Leeds Gallery Art Fund and Glasgow International, Film and Video Umbrella (FVU), www.fvu.co.uk/watch/georgina-starr-voices-of-quarantaine-part-1, accessed April 27, 2023.

Saint Louis, Elodie (2023), “Like Touring a Hall of Mirrors. Inside the Absorbing Work of Artist Georgina Starr”, Present Space, January 13, www.presentspace.com/story/spanning-video-performance-sculpture-sound-and-drawing, accessed, May 15, 2023.

Stewart, Kathleen (2010), “Atmospheric Attunenents”, Rubric, no 1, pp. 1–14, https://unswrubric.files.wordpress.com/2010/04/atmosphericattunements.pdf, accessed May 26, 2023.

Trinh T. Minh-ha (1991), When the Moon Waxes Red. Representation, Gender and Cultural Politics, New York, Routledge.

Walsh, Maria (2020), “Hearing Voices. Georgina Starr Interview”, Art Monthly, no 435, April, pp. 1–5, http://georginastarr.com/documents/Interview_Georgina-Starr-2020.pdf, accessed May 26, 2023.

Wright, Ronald (1988), Hafed & Hermes, London, Revelation Press.

Zucker, Jerry (dir.) (1990), Ghost, Paramount.

| RMO_vol.10.1_Fisher |

Attention : le logiciel Aperçu (preview) ne permet pas la lecture des fichiers sonores intégrés dans les fichiers pdf.

Citation

- Référence papier (pdf)

Jennifer Fisher, « Locked Grooves, a Circle of Hands. Paranormal Affects in Georgina Starr’s I am the Medium », Revue musicale OICRM, vol. 10, no 1, 2023, p. 138-151.

- Référence électronique

Jennifer Fisher, « Locked Grooves, a Circle of Hands. Paranormal Affects in Georgina Starr’s I am the Medium », Revue musicale OICRM, vol. 10, no 1, 2023, mis en ligne le 12 juin 2023, https://revuemusicaleoicrm.org/rmo-vol10-n1/locked-grooves/, consulté le…

Author

Jennifer Fisher, York University (Toronto)

Jennifer Fisher is a writer and curator who focusses on curatorial studies, contemporary art, performance, feminist epistemology, affect theory and the aesthetics of the non-visual senses. She is co-founder and joint editor of the Journal of Curatorial Studies. Recent writings have been featured in journals such as OnCurating, Capacious. Journal of Emerging Affective Inquiry, and books including The Ashgate Companion to Paranormal Culture. Her anthology Technologies of Intuition was published by YYZBOOKS. She is currently principal investigator of The Medium in the Museum, a SSHRC Insight research-creation project that experiments with curatorial forensics, intuition and the affective resonance of objects. She is Professor of Contemporary Art and Curatorial Studies at York University, Toronto. www.displaycult.com.

Notes

| ↵1 | The Hearing Voices Network is a London-based organization that advocates to create respectful and empowering support for people to talk freely about voice-hearing, visions, and similar sensory experiences. |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | The Voices of Quarantaine (Part 1) by Georgina Starr was commissioned by Glasgow International 2021 and Film & Video Umbrella, London. |

| ↵3 | Mum Sings Hello (1992) was featured in Georgina Starr’s exhibition, I am a Record (2009). |

| ↵4 | Another artwork that makes visible the sound of immaculate conception is the inscription of divine vocalization as an arc of golden words connecting the angel Gabriel and the Virgin Mary in Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi’s elegant 1333 painting the Annunciation with St. Margaret and St. Ansanus, at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. |

| ↵5 | My anthology, Technologies of Intuition, explores intuition contingent to processes of “coming to know” involving a range of technologies—psychometry, aura photography, mediumship, meditation, Tarot—that have been used by artists (Fisher 2006). |

| ↵6 | In the introduction, Ronaldo Wright describes how the book marks a continuation of the original nineteenth-century Spiritualist investigations of David Durguid, a famous Glasgow medium who authored the best-selling book Hafed, a Prince of Persia at the request of Spirit. |

| ↵7 | The formal logics of the locked groove have been explored in LP recordings by artists such as Christian Marclay, whose Groove (1997) side B includes six locked-groove pieces. Similarly, the Beatles, likely inspired by musique concrete, inserted a locked-groove voice segment at the end of a side on the mono uk Parlophone edition of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967) that gave the option of being played either forward or backward. |

| ↵8 | Richard Dyer (1992) has described the capacity of rhythm to convey non-representational affect. |

| ↵9 | The hand motif has persisted in Starr’s work, and appears in a Tarot deck she has been working on since 2013, the paintings for which are currently on exhibition at Pinksummer Contemporary Art in Genova, Italy. |

| ↵10 | Georgina Starr staged herself as a medium on the poster for her 2012 performance, THEDA. |

| ↵11 | Toronto psychic medium Brough Perkins has assured me that spirits only show up when they want to show up, and therefore channeling does not involve the troubling ethics of “waking up” the deceased. |

| ↵12 | Starr’s enactment of the figure of Theda Bara was prompted by her mother Christine’s resemblance to the silent movie star. |

| ↵13 | Like Starr, esoteric modes have informed the oeuvre of a range of feminist artists including Chrysanne Stathacos and Karen Finley who have used paranormal methods and agencies to generate work that participates in etheric communication. See Fisher (2006). |

| ↵14 | Affect theorist Kathleen Stewart suggests that “Atmospheres have gradients, valences, moods, sensations, tempos, and lifespans. An atmospheric fill resonates between the material and the potential” (2010, p. 8). |