Thoughts on “Onelessness”

Miles Okazaki

| PDF | CITATION | AUTHOR |

Abstract

These field notes describe a situation where the members of an ensemble have conflicting views on the rhythmic orientation of the material, including the time signature and the beginning of the time cycle. One argument presented is that these conflicts can be productive for producing rhythmic tension and dynamism. The example discussed is a rhythmic figure that the composer has made to intentionally create two opposing and equally valid interpretations of the rhythmic flow within the band. The video examples show this groove evolving over time, and demonstrate a form of ensemble playing where there is no absolute tempo or time signature, but the group is still synchronized, executing detailed contrapuntal information, and functioning creatively.

Keywords: “Dog Star”; groove; meter; Miles Okazaki; rhythm; synchronization.

Résumé

Ces notes de terrain décrivent une situation dans laquelle les membres d’un ensemble présentent des points de vue divergents concernant l’orientation rythmique du matériau, incluant la métrique et le point de depart du cycle temporel. L’un des arguments avancés est que ces conflits peuvent être productifs en générant tension rythmique et dynamisme. L’exemple proposé concerne une figure rythmique que le compositeur a conçue afin de créer intentionnellement deux interprétations opposées et également valides du flux rythmique au sein du groupe de musiciens. Les exemples vidéo montrent l’évolution de ce groove au fil du temps et illustrent une forme de jeu d’ensemble où il n’existe ni tempo absolu ni structure métrique stricte, mais où le groupe reste néanmoins synchronisé, chacun participant à la complexité contrapuntique et fonctionnant de manière créative.

Mots clés : « Dog Star » ; groove ; métrique ; Miles Okazaki ; rythme ; synchronisation.

Thoughts on “Onelessness”

These field notes are a look at a rhythmic figure with a dual identity. I’ve written many of these rhythmic illusions over the years, but this one is probably the most successful in its ability to shift perception when looked at from different angles. For context, I am a guitarist and composer in NYC, with a dozen or so albums, 30 years of touring experience, and 15 years of teaching (University of Michigan, Princeton University). Most of the projects that I’ve worked with as a sideman deal with advanced rhythmic executions. A selected list would include Steve Coleman, Matt Mitchell, Henry Threadgill, Aka Moon, John Zorn, Patricia Brennan, Miguel Zenón, and Dan Weiss. I lead a number of projects, but the one I’ll be discussing here is a band called Trickster, which deals primarily with mischievous rhythmic ideas in combination with a funk aesthetic.

Some time ago, I became interested in the idea of synchronization without agreement between players in an ensemble. This has something to do with many ways of knowing or feeling a thing, where there may not be a single correct interpretation or description of what’s going on, even though the musical act appears to be organized. These notes will discuss a single small example to illustrate this idea.

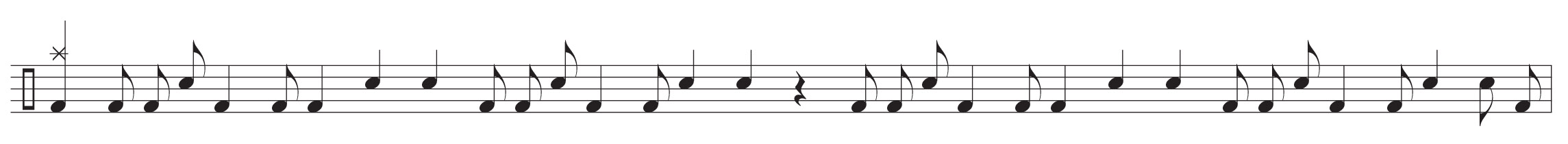

In 2015, I wrote a figure for the drums, a skeletal outline using the snare and kick drum.1The crash cymbal beginning the groove is a common way for drummers to mark the form. Here it helps synchronize the players, without necessarily indicating a downbeat. It’s nearly the same phrase twice, with some small differences at the beginnings and endings:

Figure 1: The “Dog Star” groove, for bass and snare drum.

In a rehearsal, I presented this groove by singing it without any description or explanation. It’s not a particularly difficult figure, so everyone picked it up pretty quickly and was able to start playing on it. Here’s the interesting thing—if I started the groove by just singing or playing, everything was fine, but if I counted it off the band played in two different speeds. The drummer (Sean Rickman) was hearing this:

Figure 2: “Dog Star’’ groove in duple time.

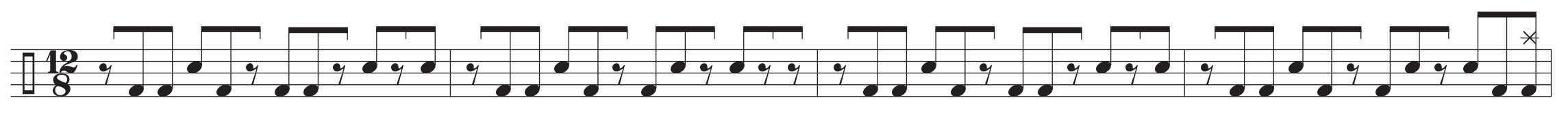

And the bassist (Anthony Tidd) was feeling it like this:

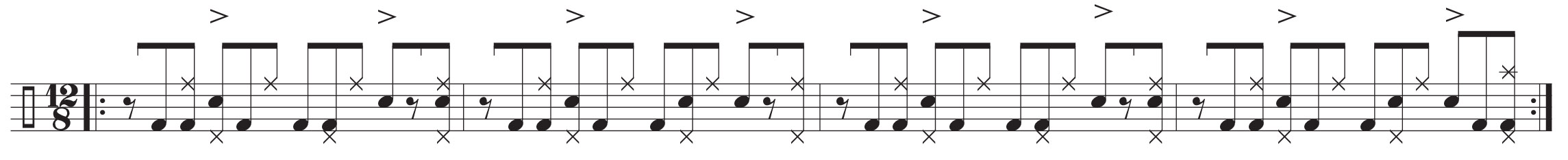

Figure 3: “Dog Star’’ groove in triple time.

This wasn’t really by accident. I had designed a groove where you could feel a backbeat in two different ways. In music that comes from the blues, rock, funk, jazz, gospel, and other versions of Black American Music, the backbeat is the most important signifier of where the beat is. It’s the compass that points the direction for the rest of the band. So, by making two possible backbeats, I was purposefully sabotaging the interpretation of the groove, or at least muddying the waters. By only hearing me sing the part, the drummer was feeling duple time (16th notes in three bars of 4/4), and the bassist was feeling triple time (four bars of 12/8).2The sixteenth notes in Figure 2 and the eighth notes in Figure 3 are equivalent. In both cases, there are backbeats on the snare on 2 and 4 (indicated with accents in Figure 4):

Figure 4a: “Dog Star” groove in duple time with backbeats accented.

Figure 4b: “Dog Star” groove in triple time with backbeats accented.

What you might notice here is that not only are the musicians playing at two different speeds, they also feel the “one” in a different spot. The drummer feels the crash on the downbeat of the cycle, and the bassist feels that same hit on the last triplet at the end of the fourth bar, as an anticipation of the downbeat. When this is happening, there’s no way to count off a tune with a single “correct” tempo. The only way to do it is to just start playing and let everyone feel it the way that they feel it.

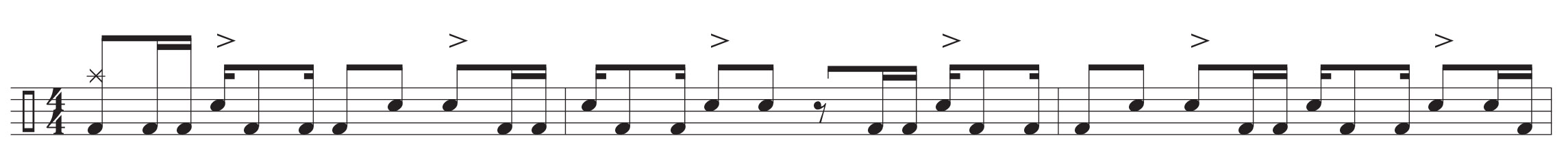

As we continued to rehearse the tune, the drummer began adding the other two limbs (left foot, right hand). The hi-hat naturally fell on the beats that Sean was hearing, and with the right hand he was playing various things on the cymbals. I asked Sean if he could accent threes on the ride to give the bassist a pulse to lock into. So he naturally just put threes over the whole thing, starting with “his” downbeat:

Figure 5: “Dog Star” groove, duple feel, ride cymbal added.

The thing is, when this groove is felt in triple, the ride cymbal falls on the last triplet of each beat, instead of the downbeat (again, because there is a disagreement about where the “one” is):

Figure 6: “Dog Star” groove, triple feel, ride cymbal added.

Rather than correct Sean by telling him to move the ride figure one note later to align with the triple beat, I just left it alone. It’s more important to me that the groove feels natural to the player than to have it follow any particular rule. But in this band, the music is highly synchronized, so it’s important for everyone to know that the ride Sean is playing is not on the beat but is in fact at the end of each beat (if you feel it in triple).

At this point, it’s useful to go to real life examples. This video from January 2016 shows the first recording of this groove, on a song called “The Calendar”:

Media 1: “The Calendar,” recording session for Trickster, 14 January 2016, Brooklyn, NY. Watch Media 1.

There are a lot of other things going on with the harmony and symbolism of the composition, but for our purposes we can just focus on the drums. In order to leave the interpretation wide open, I told Sean to begin with only the basic figure: the snare and kick drum. He does this beginning at 0:38. The composition moves through the form three times. I instructed Sean to bring in his hi-hat on the second chorus (3:17), which strongly emphasizes the duple feel. I echo this on the guitar (even though I’m feeling it primarily in triple). On the third chorus (5:53), Sean brings in the ride cymbal to shift focus to the triple feel perspective (even though he’s feeling them as dotted 8th notes). He begins with the ride on the downbeats of the triple feel, and then (at 6:27) he switches to the ride on the last triplet of each beat. It doesn’t interrupt the groove because he’s not feeling it in triple anyway.

“The Calendar” was a kind of meditation on slowly morphing harmonies, but we left it behind as a concert piece because it’s a very long form (72 bars) to get through. The groove remained and eventually became the basis of a composition called “Dog Star.” The next example shows the band playing it in a video recorded during lockdown in May 2020, after a tour was cancelled. Sean has now settled into a very strong ride cymbal at the end of each triple beat, and the bassline has become a sparse statement of triple triplets (nines) (see Media 2, 23:46).

Media 2: “Dog Star” from Trickster’s Dream, May 2020. Watch Media 2.

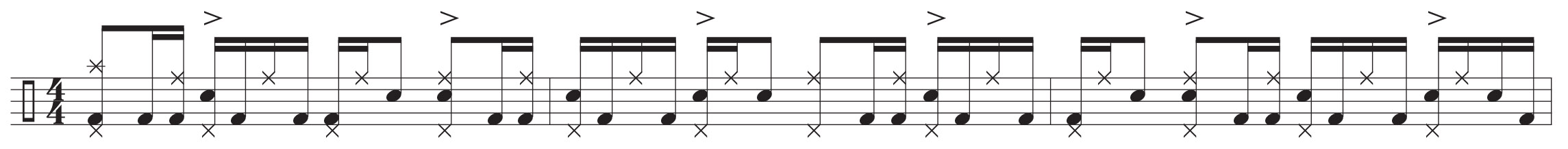

To add another twist, the melody comes in as 16th notes felt in the pulse of the triple beat (24:23). If the listener is locked into the duple feel of the drums, this melody has a very unusual relationship to it, as 16th notes nested inside of dotted 8th notes, starting on the second 16th note. Figure 7 provides a chart of this written from the perspective of the triple beat (it would be much more complicated to write it from the perspective of the drums).

In a typical process for this band, as we continued to play “Dog Star” it became useful as a rhythmic substrate for further experimentation. It could be used as raw material in combination with another composition of mine or even a song from the Great American Songbook. One example of this comes from a live concert in Brooklyn in June 2022, where we superimpose Billy Strayhorn’s “Lush Life” on the “Dog Star” strata, which eventually transposes and morphs back to the original tune. I play an unaccompanied intro stating the melody to the song and then kick off the groove (now in Db) at 23:50 (see Media 3). If you feel the groove in duple, then you have to feel “Lush Life” in three quarter time, and if you feel the groove in 12/8, then the harmonies progress conventionally in 4/4. This is because the same amount of time is either being divided into three parts (16th notes in 3/4) or four parts (triplets in 4/4).

Figure 7: “Dog Star” with bassline and melody.

Media 3: “Dog Star / Lush Life” from Trickster Live in Brooklyn, 18 June 2022. Watch Media 3.

The main thing about this groove is that it “works.” I’ve made many things that don’t work or break under too much strain. This particular groove seems to be durable and versatile, so it has become part of the lexicon of this band. What does it mean, to “work”? As far as I’m concerned as a composer, a thing works if you can play and it continues to be interesting and useful over a long period of time. The longer answer would be that the material should be interesting enough to bear repetition without becoming predictable to the listener, challenging enough to maintain the interest of the performers, have a melodic character that can be used to generate spontaneous variations, have a distinctive enough form to serve as sonic symbol, and be evocative enough to communicate some kind of movement, emotion, or meaning. I won’t hit all of these marks every time, but they are basic goals to aim for.

The sonic idea at work in the “Dog Star” groove is the multiple ways of knowing something. Dog Star is another name for Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky. I got the idea for the title when reading about the oral traditions of the Dogon of Mali, where stories dating back thousands of years include detailed astronomical information about this star system, brought to humans by alien amphibious beings known as Nommo. The information includes the fact that Sirius is a binary star, as well as the orbit period and appearance of the companion star—data only observable through modern telescopes. There is some controversy about these claims, but aside from any argument about the validity of ancient astronauts, I find it fascinating when human creativity finds multiple pathways to a similar destination. There may be a logical method that documents the linear process of arriving at a conclusion based on first principles, or there may be someone like the mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan, who explained his incredible discoveries as visions of the goddess Namagiri writing equations on his tongue during his dreams. Music to me remains a mystery, where valid results can arrive equally through measured deliberation or leaps of intuition.

One of my goals in making music is to create non-hierarchical structures. These are things that defeat any one person’s ability to control the conversation. In the case of “Dog Star,” there can’t be a count off, because we don’t feel the beat the same way or in the same place. But we can work together, because we can navigate in relation to the others. We know where the landmarks are and which way to turn. To me, the multiple ways of knowing and feeling the music within a single group give the sound a certain thickness or dimensionality that it wouldn’t have if everyone was required to hit the same marks and exist on the same plane. In this “oneless” situation, the notion of “keeping the time” is decentralized—the responsibility of staying on course is distributed between the players’ internal clocks and their abilities to synchronize them. The fabric of time can bend and stretch, and it won’t tear as long as the relative positions of the events stays intact. This all may seem like a cozy metaphor, where people who see things differently can still get along if they just find common ground. But in my experience of dealing with musicians of all different cultural and educational backgrounds, I believe this approach can go a bit deeper, into a specific form of training. In this type of music-making, how any particular person perceives or explains the situation is trivial, and the primary goal is to strike your balance in the ensemble and be able to control and predict how the movements you make affect the rhythmic footing of those who are walking the same tightrope. Balance, like rhythmic flow, is something that’s impossible to explain, but you know it when you feel it and you definitely know when you lose it.

| RMO_vol.12.2_Okazaki |

Attention : le logiciel Aperçu (preview) ne permet pas la lecture des fichiers sonores intégrés dans les fichiers pdf.

Citation

- Référence papier (pdf)

Miles Okazaki, « Thoughts on “Onelessness” », Revue musicale OICRM, vol. 12, no 2, 2025, p. 149-154.

- Référence électronique

Miles Okazaki, « Thoughts on “Onelessness” », Revue musicale OICRM, vol. 12, no 2, 2025, mis en ligne le 11 décembre 2025, https://revuemusicaleoicrm.org/rmo-vol12-n2/thoughts-on-onelessness/, consulté le…

Auteur

Miles Okazaki, Princeton University

Miles Okazaki is a NYC-based guitarist originally from Port Townsend, a small seaside town in Washington State. His credits include Kenny Barron, John Zorn, Stanley Turrentine, Dan Weiss, Matt Mitchell, Steve Coleman, Henry Threadgill, Amir ElSaffar, Darcy James Argue, and many others. He has released nine albums of original compositions on the Sunnyside, Pi, and Cygnus labels. In 2018 Okazaki received wide critical acclaim for his six-album recording of the complete compositions of Thelonious Monk for solo guitar. He is currently on faculty at Princeton University, and holds degrees from Harvard University, Manhattan School of Music, and the Juilliard School.