Meter as a Prism. Interpreting a Theme in Sibelius’s Violin Concerto

Daphne Leong

| PDF | CITATION | AUTEUR |

Abstract

The lyrical second theme in the first movement of Sibelius’s Violin Concerto presents a metric conundrum: it is notated and barred in two distinct ways. One measure of 6/4 in the exposition corresponds to two measures of 2/2 in the recapitulation. This essay in multimedia modular format explores the meaning of the metric distinction, considering 1904 and 1905 versions of the concerto and Sibelius’s correspondence; performances and performing editions; and form and meter, tempo notated and performed, and elements of resolution. A shift in metric ground, change in the way tempo is slowed down, and homecomings in key, rhythm, and instrumental color all point to a recapitulatory second theme that flows differently—more spaciously and freely—than its expository twin.

Keywords: form; interpretation; meter; notation; performance; Sibelius; theme; violin concerto.

Résumé

Le deuxième thème lyrique du premier mouvement du Concerto pour violon de Sibelius présente une énigme métrique : il est noté et mesuré de deux manières distinctes. Une mesure en 6/4 dans l’exposition correspond à deux mesures en 2/2 dans la récapitulation. Cet essai, présenté dans un format modulaire multimédia, explore la signification de cette distinction métrique en prenant en compte les versions de 1904 et 1905 du concerto ainsi que la correspondance de Sibelius, les interprétations et éditions destinées à la performance, ainsi que la forme et la métrique, le tempo noté et exécuté, et les éléments de résolution. Un changement de référence métrique, une modification de la manière dont le tempo est ralenti, ainsi que des retours dans la tonalité, le rythme, et le timbre instrumental, indiquent tous que le deuxième thème de la récapitulation s’écoule différemment—plus largement et plus librement—que son homologue de l’exposition.

Mots clés : forme ; interprétation ; métrique ; notation ; performance ; Sibelius ; thème ; concerto pour violon.

Introduction1This essay is a companion to my 2025 article “A Metric Puzzle in Sibelius’s Violin Concerto.” The “Metric Puzzle” article provides a more extended treatment of the topic, and includes many aspects not discussed here (such as Sibelius’s sketches). The current essay adopts a modular multimedia format along with streamlined content that I hope will be useful for both performers and scholars. It also spends more time on practical issues, such as bowing. The essay and article owe their existence to many people. Lina Bahn, violinist, first approached me with the puzzle. My visit to the Sibelius Academy in September 2022 at the kind invitation of Lauri Suurpåå motivated my further … Continue reading

In Sibelius’s Violin Concerto—a cornerstone of the repertoire—the first movement reaches an expressive high point with its intensely lyrical second theme. The theme, while apparently simple, presents a metric conundrum: it is notated and barred in two distinct ways. As shown in Figure 1 (in the centre of the circle below), one measure of 6/4 in the exposition corresponds to two measures of 2/2 in the recapitulation. Listening to the theme, however, the two iterations sound similar: both are transcendent outpourings of feeling.2Clarke (2019, pp. 160–163).

On the popularity of the concerto, see, for instance, Haapakoski 1996 who found that from 1990 to 1996 the Sibelius Violin Concerto was the fifth most recorded violin concerto, after Tchaikovsky, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, and Brahms. Is the metric distinction then a mere notational artefact, or does it carry a deeper meaning? In performance, does it ultimately matter?

We will find that the metric notation is but a clue to Sibelius’s transformation of the theme from exposition to recapitulation. To arrive at this conclusion, we will consider the context around Sibelius’s metric notation, viewing the concerto through the lenses of compositional process, performance practice, and score analysis.3On this transformational network view, see Leong (2016, p. 5). The circle diagram below depicts our investigation: at its center are Sibelius’s distinct metric notations of the theme, and around its perimeter are facets that play into the interpretation of that theme. Readers may follow the argument in order (beginning at “time in Sibelius’s music” and moving clockwise) or may peruse the facets (click on any node) to arrive at their own interpretation.

Figure 0: Meter as a prism: the secondary theme and facets of interpretation.4Figure 2 can also be found at the end of this document.

After a brief literature overview (“time in Sibelius’s music”), we consider conducting practice (“conducting”), compositional process (“1904 vs 1905 versions”), distinctions in the theme between exposition and recapitulation (“form and metric ground”—“tempo”—“resolution”), and editions used in performance (“performing editions”), with a view to interpreting the theme’s distinct metric notations. Sibelius’s own comments are incorporated throughout. My interpretation is presented in “meter as a prism.”

One key aspect of my process is not included on the circle, but colours it: my experience rehearsing, performing, and discussing these passages as collaborative pianist with violinists Jinjoo Cho, John Haspel Gilbert, Ken Hamao, and Victor Avila Luvsangenden and violists Jessica Bodner, Philipp Elssner, Edward Klorman, and Daniel Moore (playing the orchestral viola solo). These collaborations ground my practical and musical understanding of the issues at hand. I owe innumerable insights and the joyful experience of playing together to my collaborators.5See the bibliography for a list of our lecture-recitals and presentations.

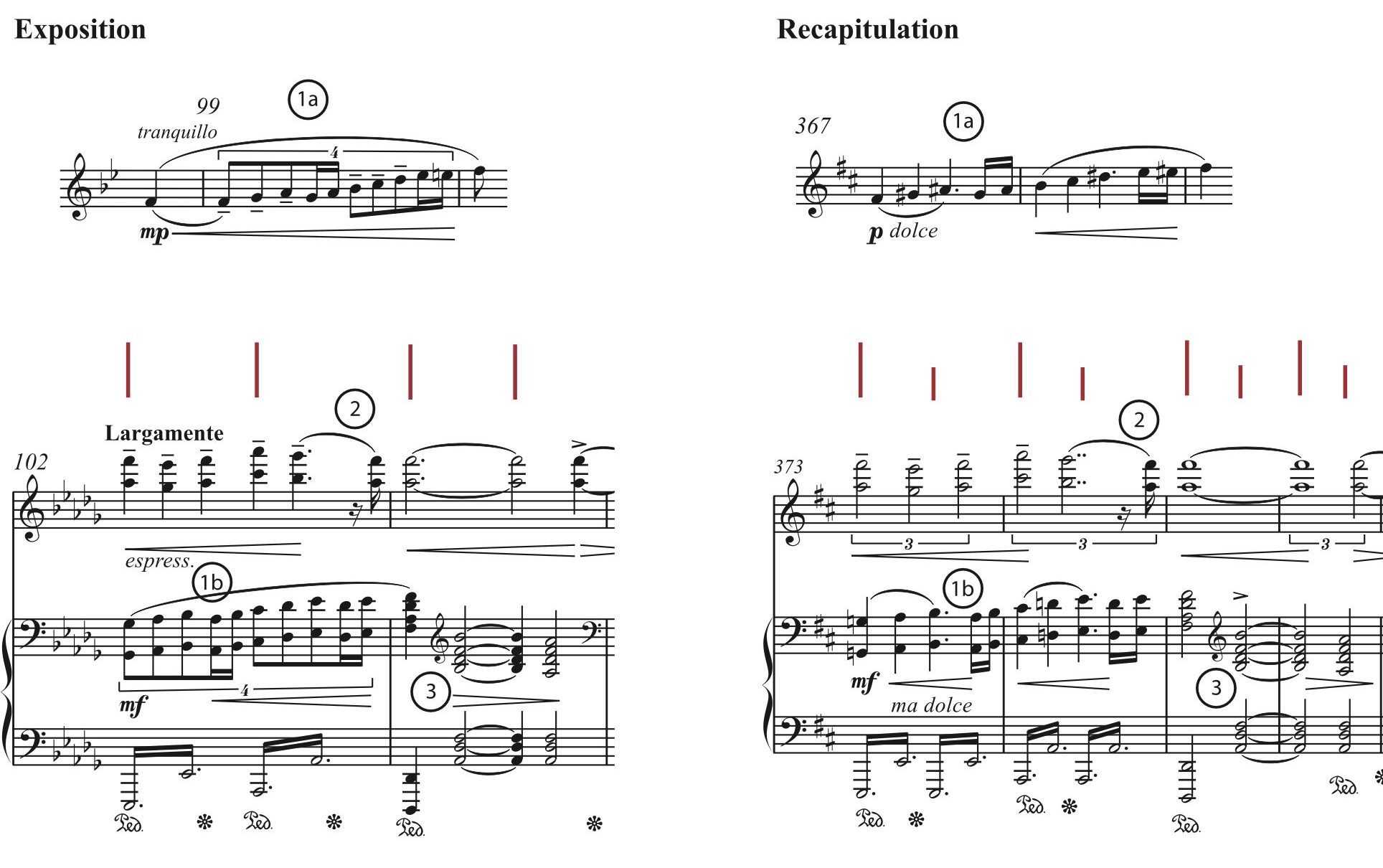

The reader is invited to refer throughout this essay to Figure 2 (click the bottom of the circle above), which compares the violin-piano score of the secondary theme in exposition and recapitulation. The score is taken from the critical edition (Sibelius 2017); it is not a reduction, as Sibelius wrote the violin-piano score prior to orchestrating the work (Virtanen 2017a, p. ix). On the figure, S1.0 and S1.1 represent the secondary theme; S1.0 introduces the theme proper, S1.1.6Following Hepokoski and Darcy (2006), I use superscripts to indicate formal sections, here defined by thematic content and other elements of surface design, but not necessarily (unlike Hepokoski and Darcy) by cadences. For a detailed discussion of how Sibelius frequently avoids or obscures cadences in the concerto, see Väisälä (2017). Corresponding passages in Figures 2a and 2b face one another.

Time, Tempo, and Meter in Sibelius’s Music

We begin with a very brief survey of literature on temporal aspects of Sibelius’s music.7For a fuller discussion, as well as an overview of the voluminous literature on the Violin Concerto, see Leong 2025.

Writers frequently note Sibelius’s unique sense of time. Characteristic is Tim Howell’s (2001, p. 40) remark that Sibelius’s music “seems, at one and the same time, to be both static and dynamic, slow- and fast-moving, repetitive yet varied: in short, music that involves contradictory perceptions of time.” Howell (1998) considers how Sibelius expresses both “time and timelessness” by synthesizing an active foreground (characterized by temporal variation) and a static background.

Tempo is oft treated. Many writers (such as Fantapié 1995, Hepokoski 1993, Lowe 2011, Pickett 2003, Ueda 2023, and Väisänen 1998) examine performed tempi in the symphonies and other orchestral works. They consider Sibelius’s own conducting and both contemporaneous and more recent performances, in relation to editions, questions of form, and the composer’s own statements. Fantapié (1995), writing for conductors, highlights the importance of the global tempo and the particular challenge of regulating layers of faster-moving pulses—both especially significant for our theme.

With regard to notated meter and cross-rhythms, Tapio Kallio (1998, 2001, 2003) considers passages in which the perceived meter does not correspond to the notated meter. Donald Tovey (1981, pp. 207–208), speaking about the violin concerto, remarks that “the style of Sibelius is nowhere more distinguished than in its novel and inevitable cross-rhythms.” Tovey cites mm. 97b–100 in the first movement; we shall see (in our discussion of the 1904 and 1905 versions) that the cross-rhythms in this passage were not at all “inevitable.”

Given the close attention paid to time, tempo, and notated meter in Sibelius’s music, it is particularly surprising that the metric puzzle in the iconic concerto has not yet been examined. This essay addresses that gap.

Conducting

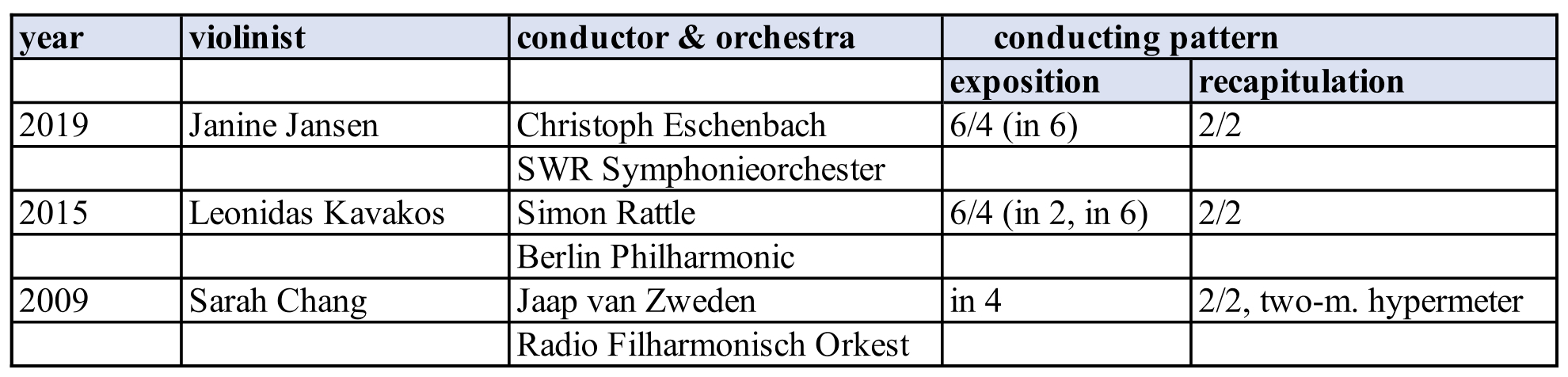

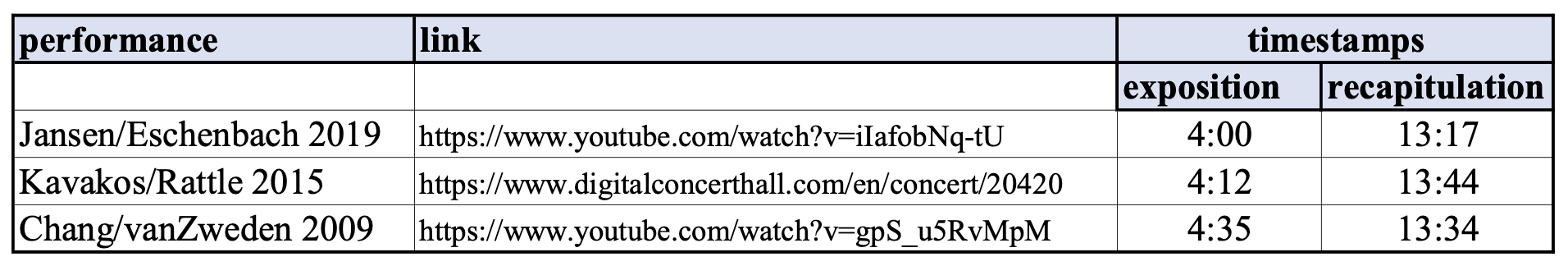

What basic choices do conductors make in approaching these passages? Three video performances, chosen because one can see the conductors’ gestures, illustrate conducting patterns. The internationally known performers are listed in Figure 3a. The reader is invited to watch these excerpts (Figure 3b) in tandem with the scores in Figure 2.

Figure 3a: Conducting patterns for the secondary theme.

Figure 3b: Conducting patterns: links and timestamps.

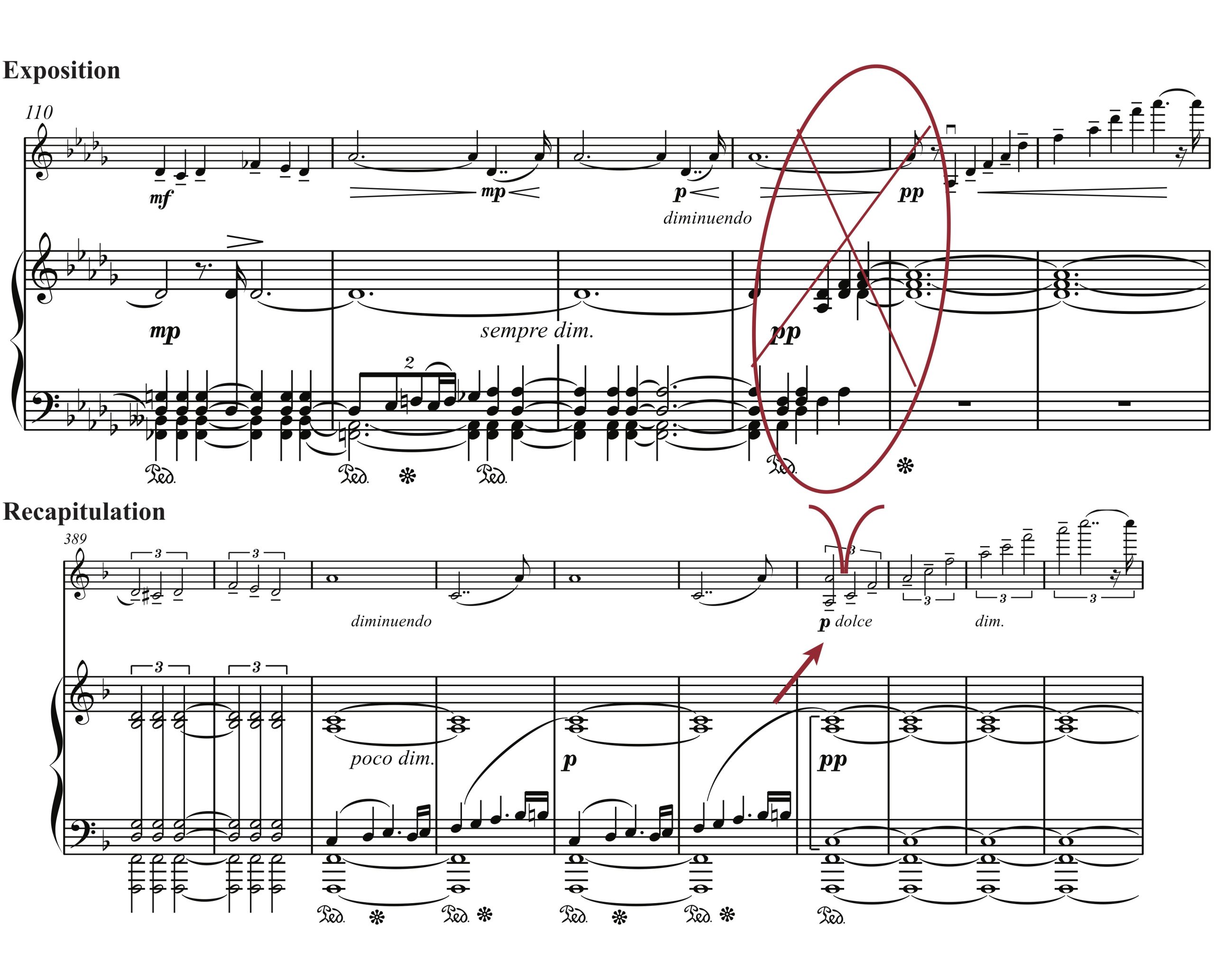

As shown in Figure 3a, Christoph Eschenbach (2019) conducts the secondary theme (S1.1 on Figure 2) as Sibelius notated: the exposition in 6/4 (in six) and the recapitulation in 2/2. Simon Rattle (2015) conducts the exposition in 6/4, alternating between a large two and six beats per measure (the latter guiding the string chords); he conducts the recapitulation in 2/2. Jaap van Zweden (2009) conducts the exposition in four, and the recapitulation in 2/2 with a clear two-measure hypermeter, that is, roughly equivalent to the meter he gives in the exposition.

As can be seen in Figure 2, at S1.1, conducting patterns align either with the soloist or with the orchestra. Conducting in six coordinates with the solo violinist and with the orchestra’s answering chords (exposition, mm. 103, 105). The orchestra, however, must play its contrapuntal line in a 4-against-3 cross-rhythm. Conversely, conducting the exposition in four or the recapitulation in 2/2 grounds the orchestral line; the solo violin then plays in a 3-against-2 cross-rhythm.

Sibelius himself conducted the 1904 version of the concerto several times (including the premiere and two repeat performances), and the final, 1905, version once (March 1924, with violinist Julius Ruthström and the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic).8Virtanen (2017b, p. 374); Virtanen (2014, pp. ix, xii); Salmenhaara (1996a) and (1996b, pp. 40-42); see also the website of the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic: https://www.konserthuset.se/en/about-us/our-operation/festivals/grande-finale/liner-notes-and-curious-facts/violin-concerto/, accessed 12 July 2024. His conducting annotations do not tell us much about how he conducted the passages under discussion, although they do show that he thought of the material in a large duple.9For details, see Leong 2025.

Composing: 1904 vs. 1905 Versions

The finished concerto exists in two versions: 1904, the original, and 1905, the final (well-known) version. We will look briefly at the context for Sibelius’s revisions, and consider the startling changes in the theme’s function, expressive character, and formal role.

The concerto’s premiere took place on 8 February 1904 in Helsinki with violinist Viktor Nováček and Sibelius conducting the Helsinki Philharmonic Society Orchestra (Virtanen 2014, p. ix); the concert was repeated on 10 and 14 February 1904. Reception was largely positive, although Karl Flodin wrote a scathing review of the premiere.10See Virtanen (2014, p. x) for a summary of Flodin’s review. Among other criticisms, Flodin compares Sibelius’s concerto unfavorably to those by Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Bruch, Brahms, and Tchaikovsky.

Within a few months, Sibelius had withdrawn the concerto in order to revise it.11“I shall withdraw the concerto; it will appear only after two years… The first movement shall be revised …” (letter to Axel Carpelan, 3 June 1904, translated in Virtanen 2017a, p. x). He told his publisher, Robert Lienau, that he would remake the piece.12“Das Violinconzert mache ich fast neu” (NA, SFA, file box 46. n.d., quoted in Virtanen 2014, pp. x, xv). The first movement—especially the secondary-theme area—gave Sibelius the most trouble. He wrote to his wife Aino, “The first movement makes me conflicted. The others are fairly clear to me”; and a few months later, to his friend and patron Axel Carpelan, “The second theme in the [first movement of the] Concerto is now clear. If I can just get past the first movement, everything will proceed by itself.”13The first statement (26 Jan 1905) is cited in Virtanen (2017a, p. x); the second (April 1905) in Virtanen (2014, p. x).

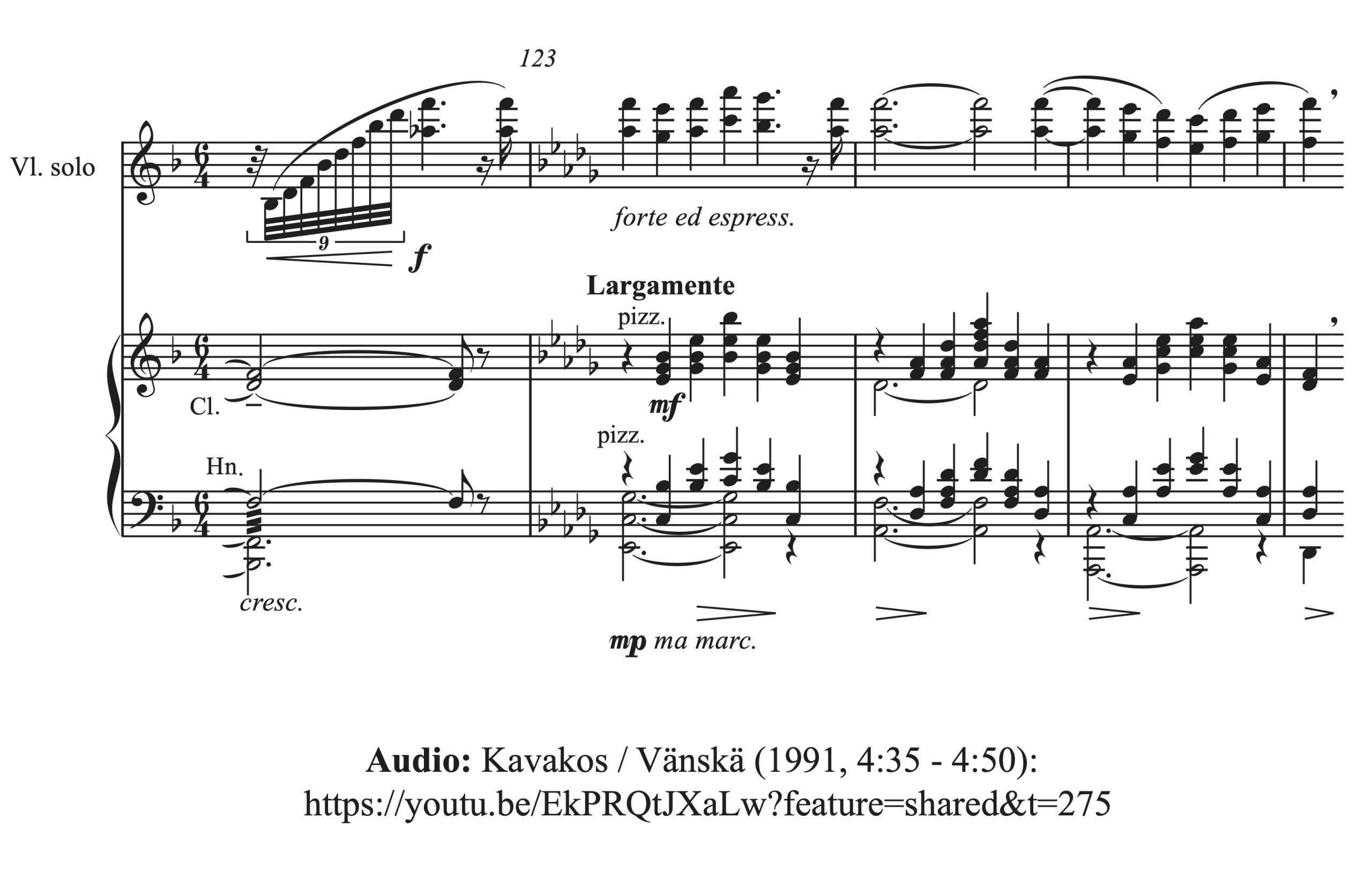

In 1905, Sibelius greatly streamlined the secondary-theme area, excising a “Mendelsohnian” episode and a weighty cadenza,14This cadenza (which does not appear in 1905) is often called a “second” cadenza, falling after the mini-cadenza of the exposition and the first cadenza comprising the sonata form’s development section. while adding more heft to the theme proper. Figure 4 shows S1.1 in 1904: a graceful melody that consists of only four measures, in major (followed by transitional material). The theme remains in 6/4 in both exposition and recapitulation. Compare to Figure 2a: in 1905, the four measures of 1904 (a1) are extended by a consequent (a2’) that moves to the minor mode, up to scale degree 5 from scale degree 3 and to octaves from sixths, before plunging to the intense depths of the violin’s low register in a single line that is subsequently echoed and fragmented. And Sibelius introduces a game changer: a counter-theme (x) in the orchestra in quadruple meter. It is difficult to overstate the rhythmic and expressive effect of this new counterpoint: no longer is the secondary theme an uncomplicated lilting melody, but an utterance of emotional depth and range, taut against a contrasting duple pulse. Further, the rebalancing of the roles of soloist and orchestra—the latter no longer mere accompaniment—underlines the transformation of the secondary-theme area, from a series of display episodes with a dedicated cadenza (1904), to a rhetorical focus within a tight symphonic trajectory (1905).15In 1943 Sibelius even told his son-in-law, the conductor Jussi Jalas: “the accompaniment of the violin concerto shall be rehearsed like a symphony”—though in 1930 he worried about the orchestra being too heavy. “I would still like to alter the orchestral accompaniment. It is too heavy. Like a symphony.” (The first statement is recorded in Jalas’s 1943 notes, NA, SFA, file box 1; the latter is found in a letter to Sibelius’s publisher Robert Lienau. Both are cited in Virtanen 2014, pp. xiii, xvii.)

Figure 4: Secondary theme, 1904, exposition, mm. 122–126.

Analyzing

The remainder of this essay will focus on the final, 1905, version of the concerto. We will consider just how the secondary theme differs between exposition and recapitulation, weighing the import of these differences.

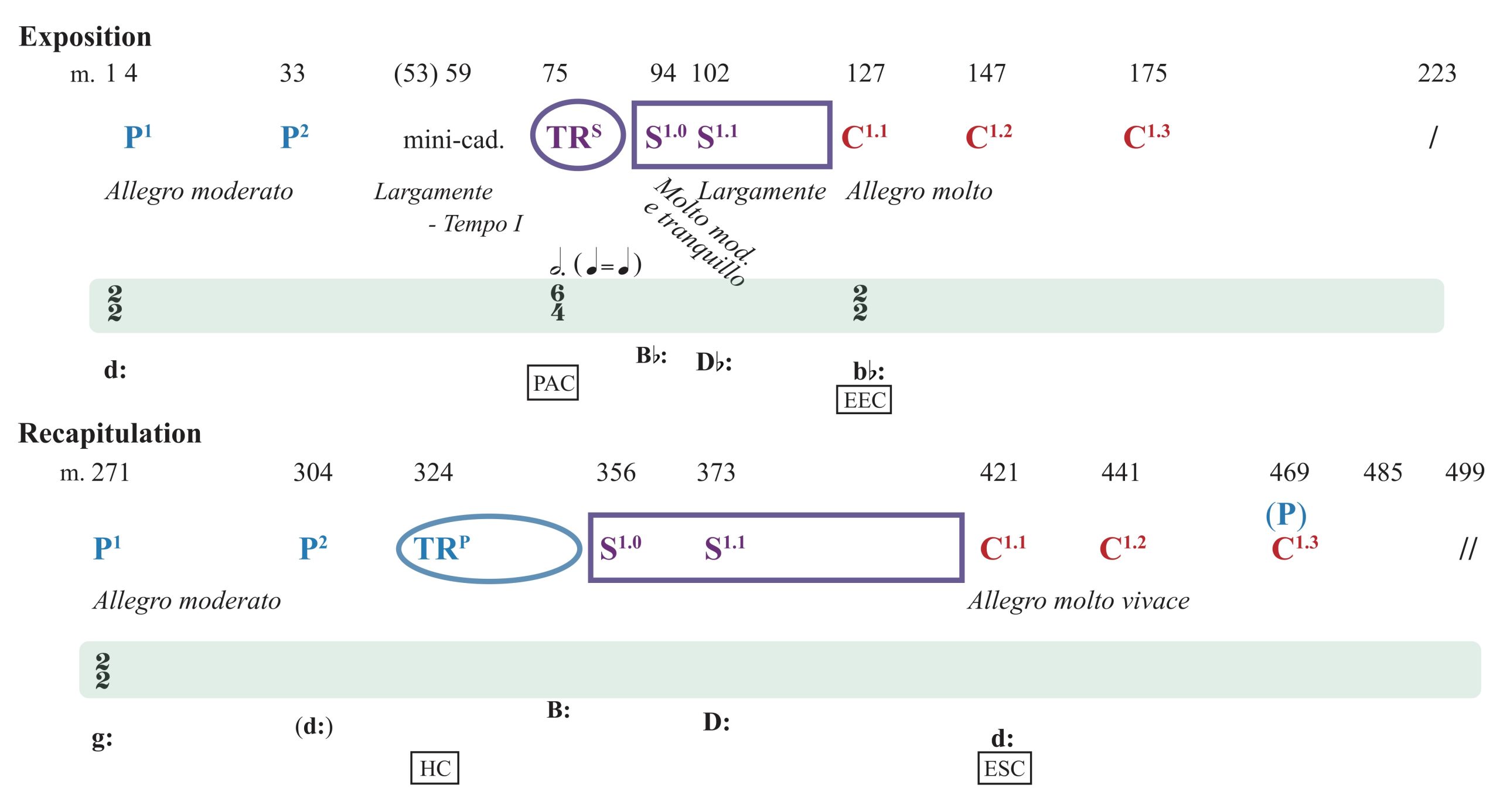

Form and Metric Ground

Figure 5 compares the formal layout of the exposition and the recapitulation; horizontal proportions roughly correspond to temporal ones. P indicates the primary theme, TR the transition, S the secondary theme, and C the closing theme. Superscripts indicate sections and subsections.

Figure 5a: Form: exposition and recapitulation.

Figure 5b: Form: audio.

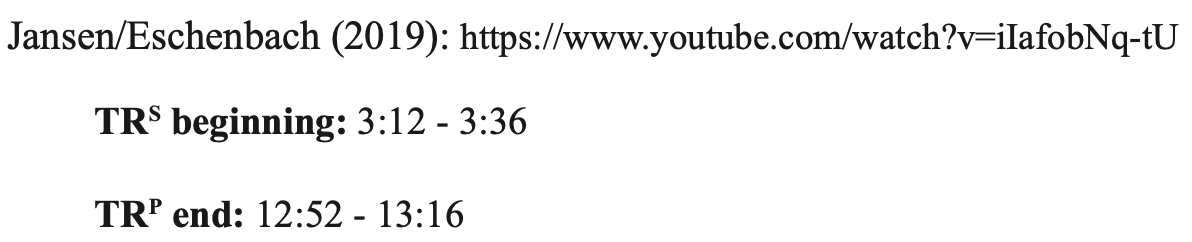

In the exposition, it is at the transition section TRS—based on S material—that the notated meter changes from 2/2 to 6/4 (keeping the quarter note constant). In the recapitulation, instead of TRS, a heroic transition TRP—based on P material—precedes the S theme. The notated meter remains the same—2/2—throughout the recapitulation. The reader may wish to listen to TRS and TRP at the link given on the example; TRS clearly expresses 6/4 and TRP, with a full brass section, 2/2.16Mäkelä (1995) points out the unusual heft of the orchestra, which features three trombones.

Figure 6: Metric context.

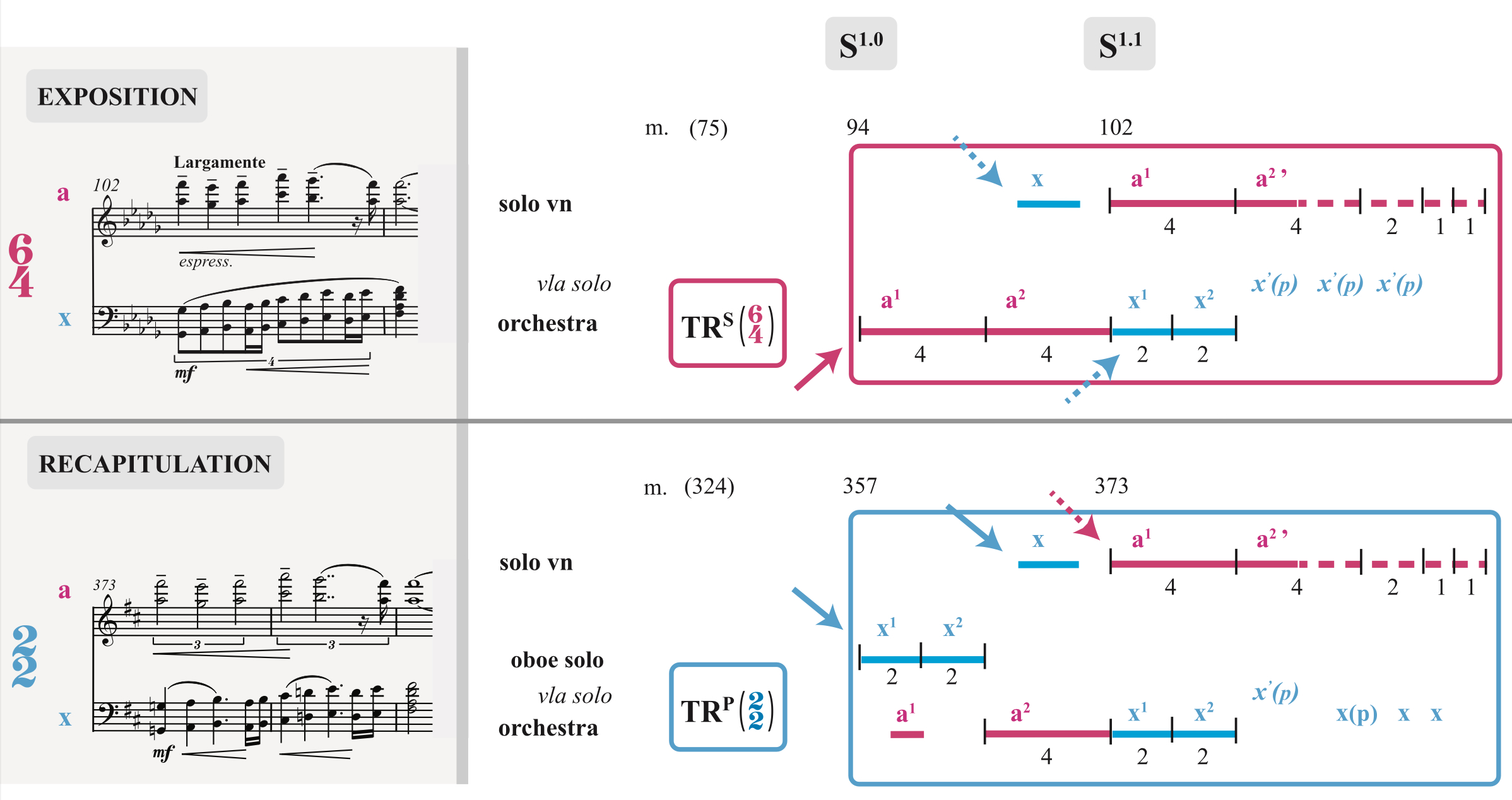

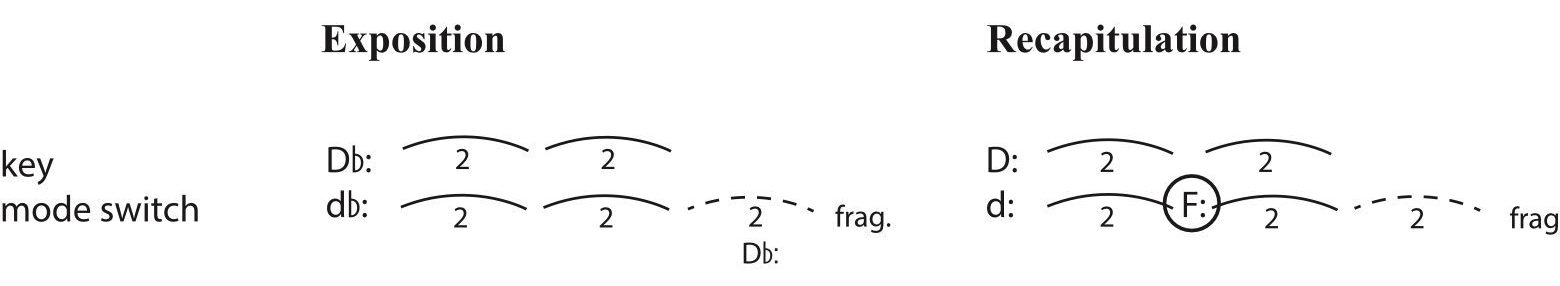

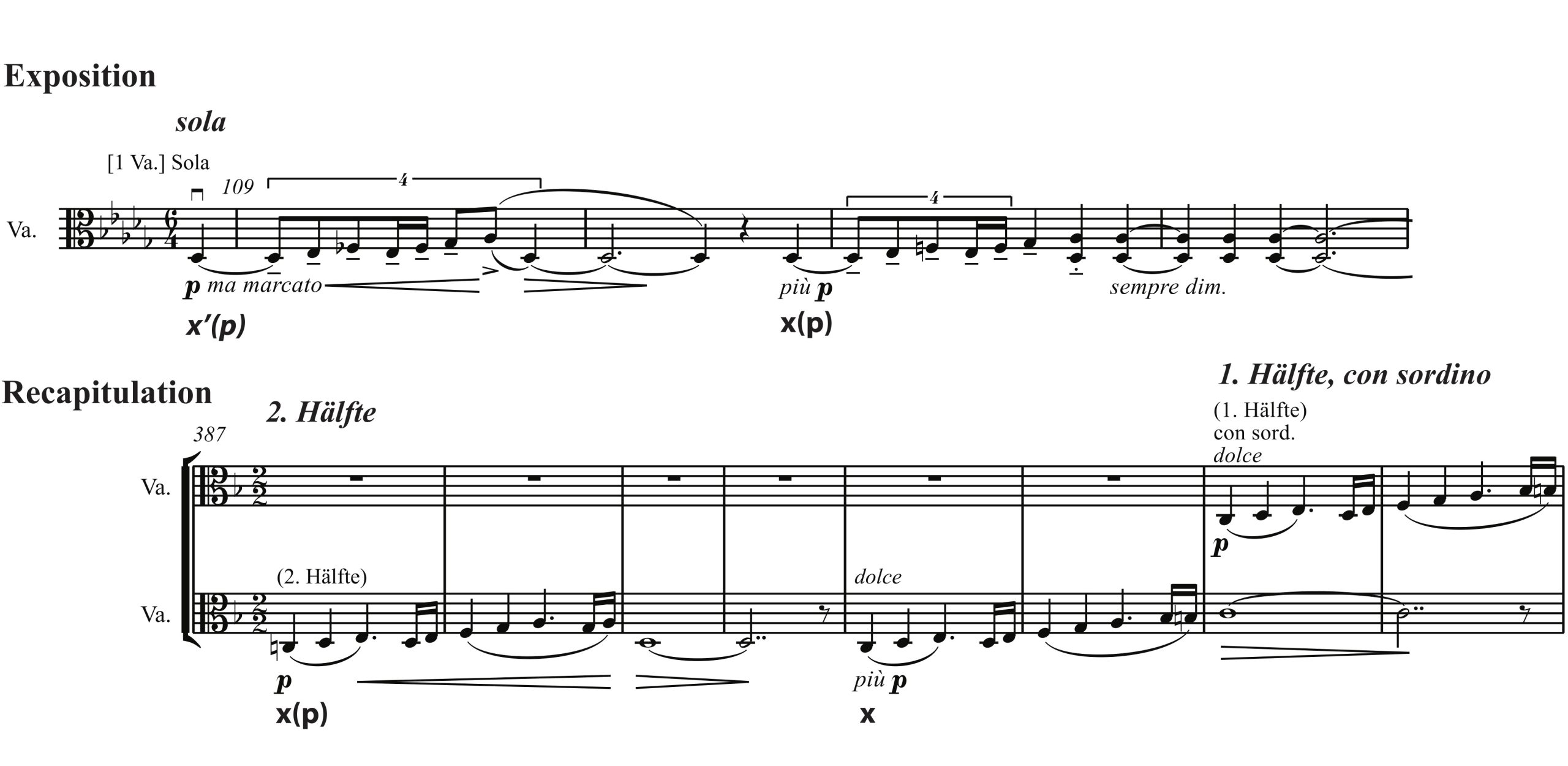

Figure 6 zooms in on the approach to S1.1, the secondary theme proper, in exposition and recapitulation; these annotations also appear on the score in Figure 2. Lower-case “a” represents the theme (in 6/4 or compound duple); a1 labels material centred on scale degree 3, and a2 that centred on scale degree 5. Lower-case “x” indicates the counter-theme (in simple quadruple); x, x1, and x2 each rise approximately through an octave; x’(p) consists of the counter-theme head motive closing with the P motive. Arabic numerals 4, 2, and 1 indicate numbers of measures (the recapitulation’s double measures are counted as single measures, to correspond to the exposition).

Metric foreground and background switch, from the exposition’s 6/4 context to the recapitulation’s 2/2 setting. In the exposition, the lengthy TRS transition in 6/4 prepares the theme proper; at S1.0 the orchestra’s “a” material, still in 6/4, introduces it. When the solo violin enters with counter-theme x, its quadruple rhythm thus subverts the predominant 6/4. And when the orchestra then takes the counter-theme at S1.1 it, too, resists the main theme’s 6/4 flow.

In the recapitulation, the heroic TRP proclaims a bold 2/2. There is no motivic transition (Mäkelä 1995, p. 129); P material simply fades out, and the oboe solo begins S1.0 with counter-theme x, also in 2/2.17The seam between TRP and S seems to have caused Sibelius trouble initially (see Leong 2025). (The cello section comments with a1 material in half-note triplets.) When the solo violin enters this time, the quadruple rhythm of its counter-theme x simply carries on that of the oboe. At S1.1 in the recapitulation, then, perhaps the solo violin’s compound duple functions differently from before; perhaps it broadens and sweetens the orchestra’s 2/2, rather than undergirding it.

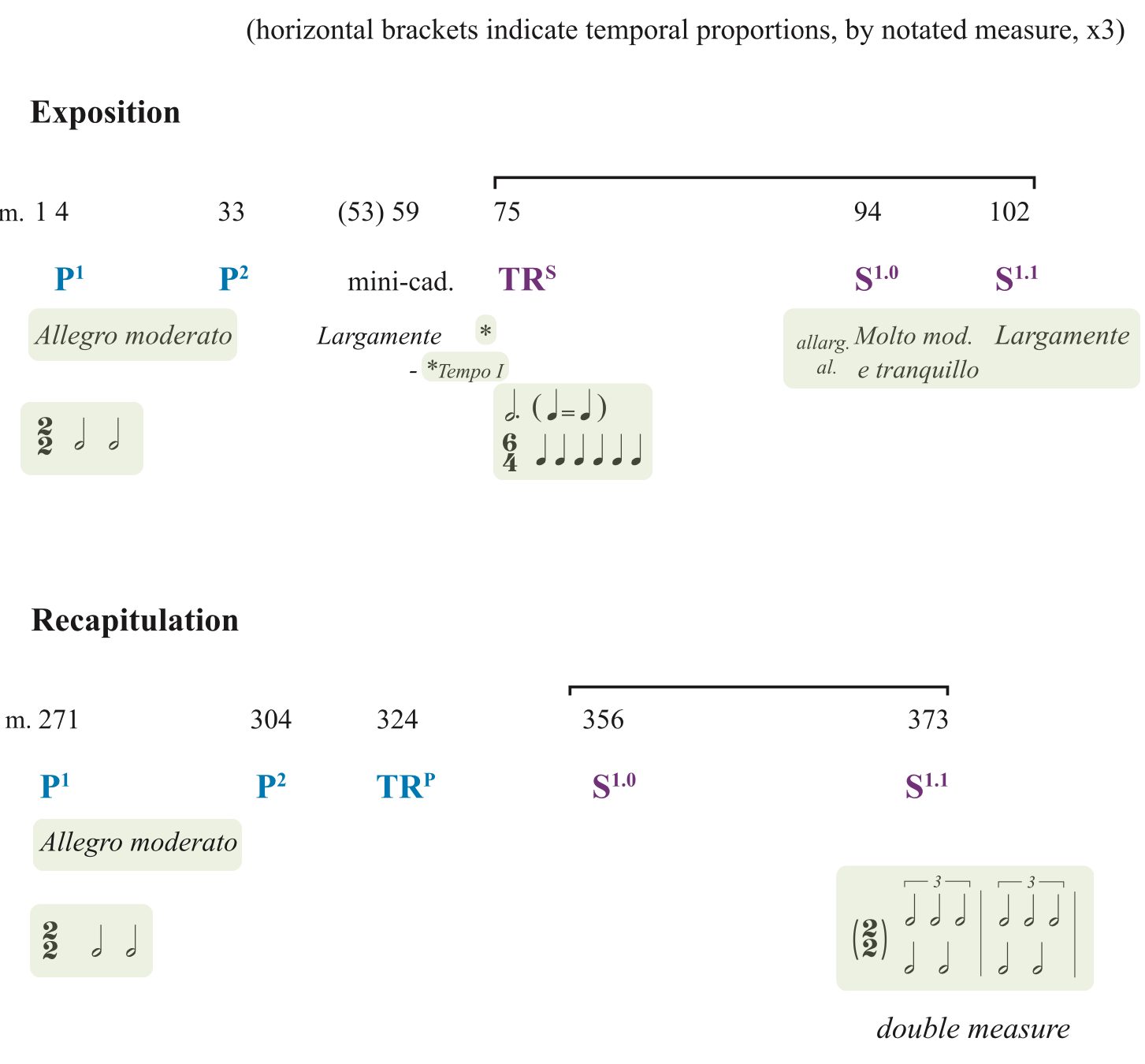

Tempo

The movement’s tempo trajectory goes hand in hand with the two different metric notations of the secondary theme. Figure 7 contrasts the notated tempo changes in exposition and recapitulation. (Horizontal proportions in the secondary-theme area have been tripled, to provide room for annotations.)

Figure 7: Tempo changes in exposition and recapitulation: primary- to secondary-theme areas.

In the exposition, the tempo slows from the Primary theme’s Allegro 2/2 first by modulating, at TRS, to 6/4 (keeping the quarter note constant), then through the allargando al Molto moderato (S1.0), finally reaching Largamente (S1.1). In the recapitulation, the direct move from Primary- to Secondary-theme material allows Sibelius to use the notational technique of the double measure. Two notated measures represent one “actual” measure, slowing the tempo without changing the notated meter or the tempo indication.18Mirka 2013 traces the developing independence of notated and actual meters (which she calls “composed meters”) in Classical practice, showing how their decoupling facilitated stylistic cross-references. Such cross-references certainly feature in Sibelius’s secondary theme. For the double measure, see Mirka (2013, p. 365 ff.). The Primary theme’s Allegro 2/2 thus remains in effect throughout—but the tempo is halved “under the table.” (As a corollary, the recapitulation’s open noteheads suggest an “exalted” affect, in comparison to the “terrestrial” connotations of the exposition’s black-note 6/4.)19See Allanbrook 1983, p. 22 and Mirka 2013, pp. 360–361.

In the 1904 exposition, TRS is notated in 3/2 half notes, with w = w . , equivalent to the double measure in the 1905 recapitulation. In 1905, Sibelius saves this more weighty version for the recapitulation.

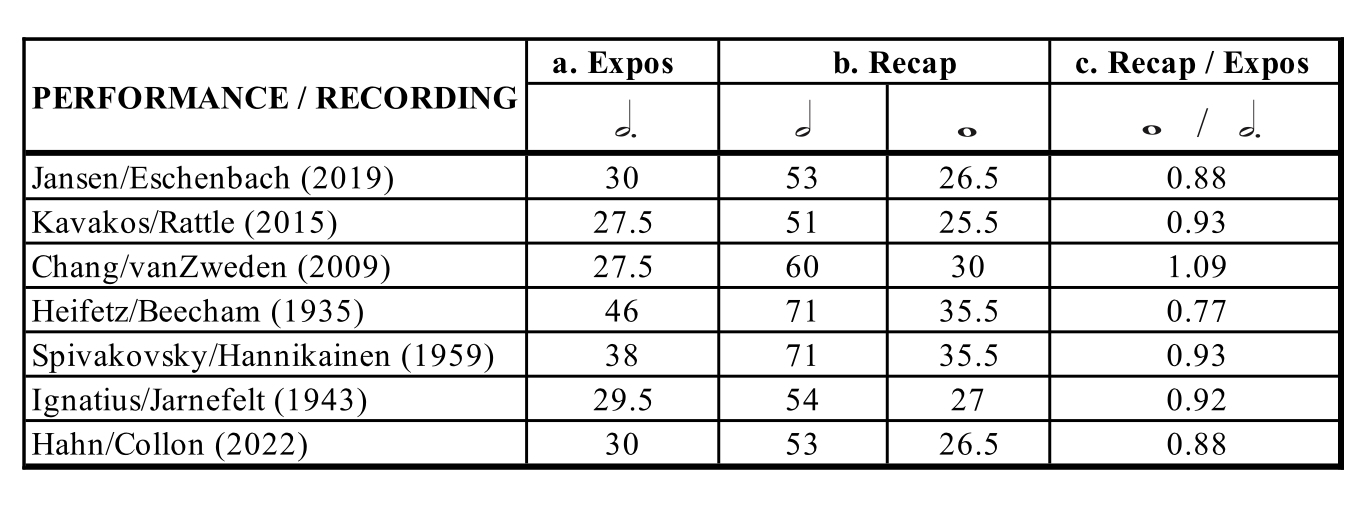

Let us consider how performers interpret the tempo of the theme proper, S1.1, in exposition and recapitulation. We’ll consider seven renditions: four modern and three historical. To the three live modern performances discussed earlier under “Conducting,” we add Hilary Hahn’s live 2022 performance with Nicholas Collon and the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, for a tempo trajectory that differs from the others. For historical recordings, we reference Jascha Heifetz’s 1935 recording with Sir Thomas Beecham and the London Philharmonic Orchestra, the iconic first recording, which “established [the concerto] as core repertory for virtuoso violinists” (Ramnarine 2020, p. 89). Anja Ignatius’s 1943 recording with Armas Järnefelt and the Städtisches Orchester Berlin was the first to feature a Finnish violinist; Sibelius had proposed that Ignatius and Järnefelt (Sibelius’s brother-in-law) record the concerto for Deutsche Grammophon (Salmenhaara 1996b, pp. 40-42; Virtanen 2014, p. xiii). Tossy Spivakovsky made an acclaimed if somewhat idiosyncratic recording in 1959 with Tauno Hannikainen and the London Symphony Orchestra (Ramnarine 2020, p. 90). This small sample, though by no means comprehensive, provides a view of different modern and historical approaches to tempo in our passages.

Figure 8: S1.1 performed tempi (bpm), and comparisons within each performance.

Figure 8a–b lists performed tempi for S1.1 in exposition and recapitulation.20For the recapitulation, tempi for both the notated pulse ( h ) and the double measure’s pulse ( w ) are indicated.

See the Appendix for a description of the methodology used to determine performed tempo.

Leong 2025 examines performed tempi at other key points. Figure 8c compares the equivalent pulses in exposition and recapitulation, and shows that in all of our performances but one, S1.1 unfolds more broadly in the recapitulation than in the exposition.21Only Chang/vanZweden (2009) take the recapitulatory secondary theme faster than the expository one. Indeed, tempo and sense of time may be one way in which the recapitulatory second theme differs affectively from the expository theme. This slower recapitulatory S1.1 tempo, intriguingly, is Janus-faced: both slower and faster since the “actual” tempo (the measure) is slower than in the exposition, but the conducted tempo (the half note in 2/2) is twice as fast. The theme thus expresses the classic Sibelian temporal paradox: both expansive and hovering, both broad and in motion.

Performed tempo was a primary concern for Sibelius: he frequently critiqued tempi in performances of his works.22See Mäkelä (2011, pp. 58–62) for a sampling of such comments taken from Sibelius’s letters. Yet he was reluctant to supply metronome markings. On one occasion, he wrote, “I do not want any metronome specifications, because they always inhibit a personal conception.”23This statement, originally in German and quoted from Mäkelä (2011, p. 62), is taken from a letter draft in National Archive Box 36.

For the violin concerto, Sibelius left relatively few metronome markings. Metronome markings do not occur in the initial primary sources: not in the manuscripts or first editions for the concerto; not in Sibelius’s Handexemplar of the study score, or in a Handexemplar of the orchestral score annotated by Sibelius and Jussi Jalas (Sibelius’s son-in-law and a conductor), nor in Jalas’s notes of Sibelius’s remarks. In May 1929, Robert Lienau wrote to Sibelius to check whether h = 54–60 was correct for the first movement; this metronome marking was included in the Schnirlin performing edition, although Sibelius’s response is not known. The marking was not included in study scores of the 1930s. In May 1941, in response to another Lienau query about this metronome marking, Sibelius wrote that the tempo should be h = 68; this marking was included in subsequent editions (Virtanen 2017a, p. 96 and 2014, p 287). Of our seven recordings, only Heifetz/Beecham (1935) comes close to this tempo.24Heifetz/Beecham begin the movement at h = 70; the other six performances begin at tempi ranging from h = 50 to h = 59.

Resolution: Key, Rhythm, and Colour

I propose that we may consider the secondary theme in the recapitulation as resolving certain tensions from the exposition. These tensions include tonal grounding within the form and on the violin, metric grounding and rhythmic flow, and modal and instrumental colouring.

The secondary theme resolves from its foreign key (Db) in the exposition to the home key (D) in the recapitulation. The move from Db to D, for a violinist, is a move from darker to brighter, less resonant on the instrument to naturally resonant, less idiomatic to very familiar25Well-known violin concertos in D major include those by Beethoven (Op. 61), Brahms (Op. 77), and Tchaikovsky (Op. 35).—in practical attributes, from turbulent to grounded.26“Turbulent” is Jinjoo Cho’s description, in a very funny discussion of the differences between playing in Db and in D (Leong and Cho 2023 lecture-recital).

Figure 9: Secondary theme in exposition and recapitulation: rhythm.

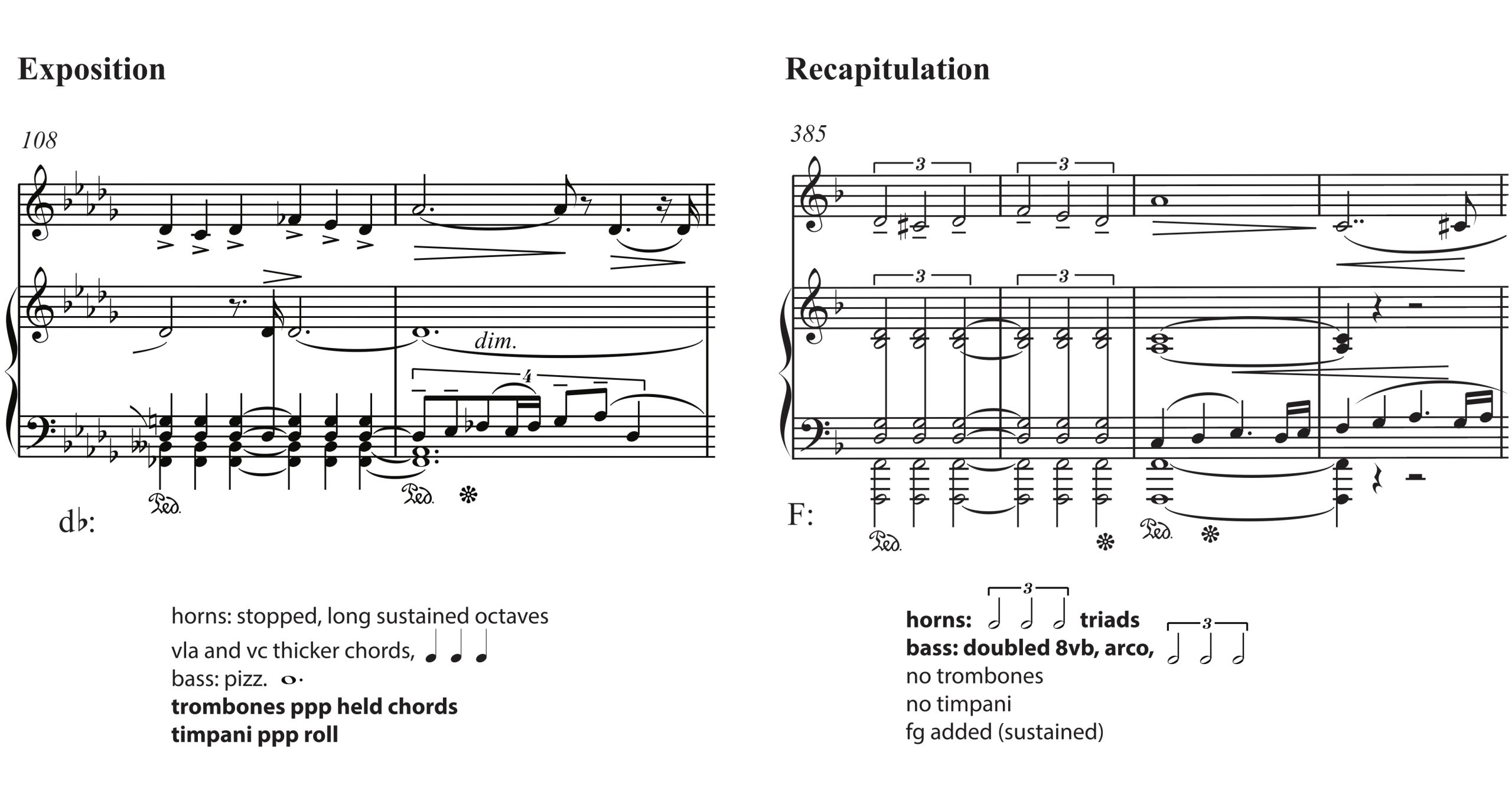

The foreign, more sensual, 6/4 meter also “resolves” to the home, more settled, 2/2 in the recapitulation.27I thank Annika Bowers for this suggestion. Figure 9 compares the rhythm of the theme in exposition and recapitulation. Numbers in the following list are keyed to the figure. 1) The counter-theme is not dotted in the exposition, but it is dotted in the recapitulation. (See 1a for the solo violin28Sibelius’s autograph piano score shows that, in the exposition, this passage was originally dotted in the solo violin—but not in the orchestra. See Facsimile III in Virtanen (2017a, p. 79). and 1b for the orchestra.) 2) The solo violin’s theme is dotted in the exposition, but double-dotted (per the doubled note values) in the recapitulation. 3) The orchestral strings’ chords occur in triple subdivisions in the exposition versus the straight duple meter of the recapitulation. In short, as shown by the hash marks above the score, the theme proper expresses a large duple meter in both exposition and recapitulation, but more clearly articulates quadruple meter (within the double measure) in the recapitulation.

In addition, Sibelius exploits modal shifts between major and minor in the secondary theme. Figure 10 shows that, in the exposition, the theme proper moves from Db major to the parallel minor and back.29Arabic numbers again represent numbers of measures in the exposition, and numbers of double measures in the recapitulation. In the recapitulation, the theme moves from D major to the parallel minor—and then to the relative major, F. This return to major occurs earlier than expected, in the body of the theme rather than in its subsequent echo and fragmentation.

Figure 10: Key.

Figure 11: Orchestration.

Subtle changes in instrumentation and expression colour this move to F major. Figure 11 compares the beginning of the F-major passage to its corresponding spot in the exposition. Darker orchestration (trombone, timpani) in the exposition is replaced by brighter and fuller sound (horns, bowed basses in octaves) in the recapitulation. At the turn to F major in the recapitulation, the solo violin plays with tenuto markings rather than the accents of the exposition.30Tenuto markings occur later in the exposition, when its theme returns to major. And the answering viola (Figure 12) transforms from solo viola to half of the viola section, from the x’(p) motive to the full counter-theme ascending (eventually) through the octave, from marcato to dolce, and—passing to the other half of the viola section—con sordino. The viola ascent, as shown in Figure 13 (see the recapitulation), transfers directly to the solo violin’s upward arpeggiation, bypassing the lull created in the exposition by the orchestral pizzicati and subsequent eighth rest. And the solo violin’s arpeggio now makes a diminuendo rather than a crescendo. Thus it is that the early move, to F major rather than D major, consoles and sweetens what had been more shadowed.31The move to F major (rather than D major) also allows Sibelius to move easily to the Closing theme in the desired D-minor key; in the exposition the corresponding relationship was Db major to Bb minor.

Figure 12: Viola counter-theme.

Figure 13: Elision: omission of orchestral pizzicati in the recapitulation.

Editing and Bowing

If we are to consider Sibelius’s concerto as a dynamic network, we must consider the texts seen by performing violinists. While the primary performing editions show no differences of note for the secondary theme proper (S1.1), they do look quite different in the introduction to that theme (S1.0). We will consider these differences because of the way they frame the theme for the violinist.

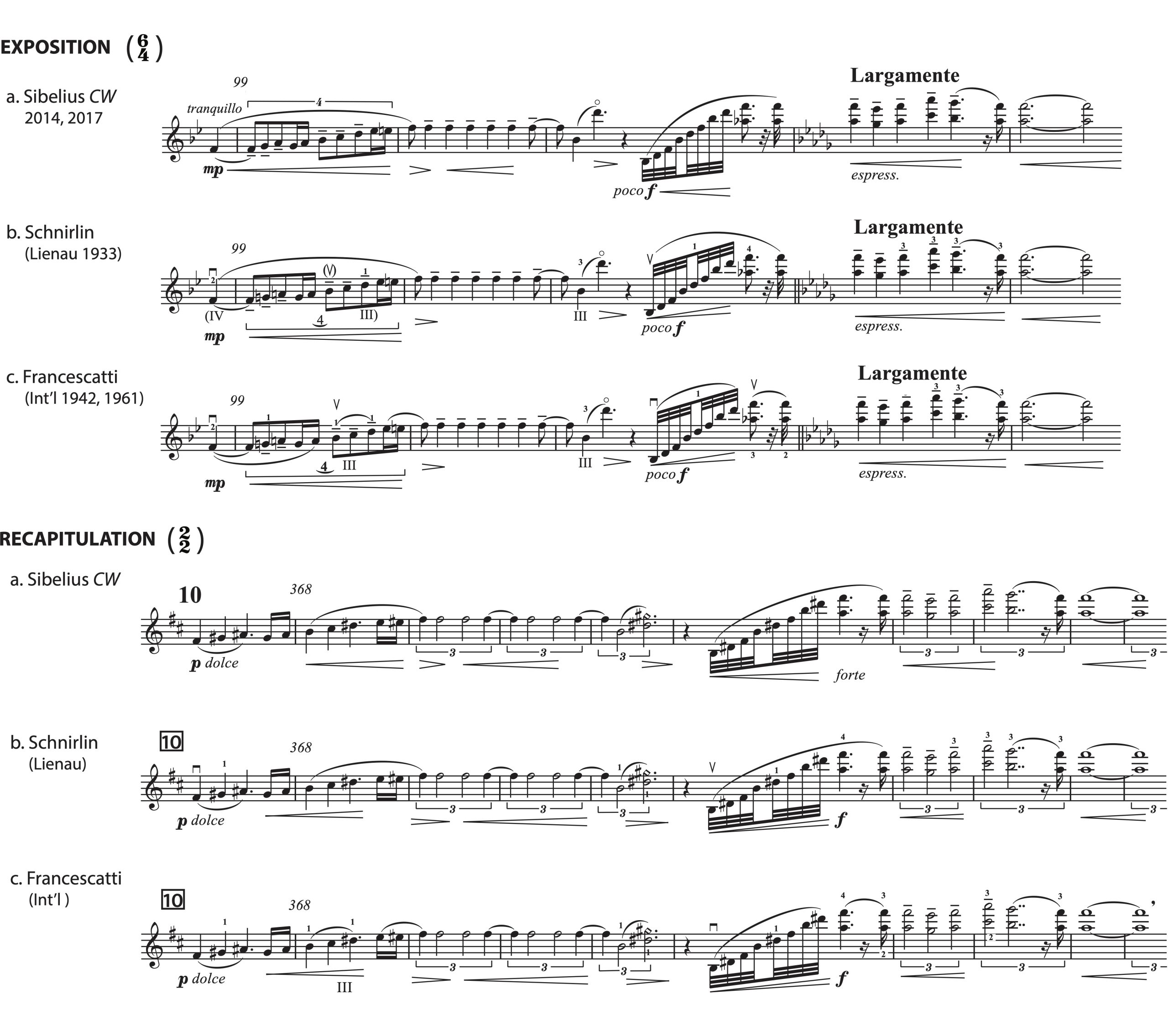

Figure 14: S1.0 in three editions: solo violin, mm. 99–103, 367–376.

Figure 14 shows S1.0 in three editions: a) the critical edition Jean Sibelius Complete Works, edited by Timo Virtanen; b) Ossip Schnirlin’s performing edition of 1933, published by Lienau; and c) the International violin-piano edition, violin part edited by Zino Francescatti with orchestral reduction by Alexandre Gretchaninoff. The International edition is widely used in North America. The Lienau editions (1905 and Schnirlin 1933) are popular in Europe.32The 1905 Lienau edition, not shown here, was the source for the 1933 Schnirlin edition. For this passage, the 1905 edition is the same as in 1933 (minus the bowing and fingering indications) but for one detail: in 1905, the initial crescendo marking begins before the barline. The Collected Works edition is also gaining currency among performers.

Sibelius’s publisher Robert Lienau initiated the Schnirlin edition in 1929, writing to Sibelius that performing indications would be helpful, and recommending Schnirlin, a German violinist, pedagogue, and student of Joseph Joachim, for the task. Schnirlin’s edition added many fingerings and bowings (along with metronome markings); Sibelius received a copy of the published edition but his response to the project is unknown.33Virtanen (2017a, pp. xii, xv) provides a detailed account of Lienau’s correspondence with Sibelius on the topic of the Schnirlin edition. Virtanen (2017a, p. 93) writes, “Whether Sibelius applied his mind to the Schnirlin edition and accepted the additions is highly questionable, even unlikely. Although the edition was printed during the composer’s lifetime and has been widely used, it has remained without further consideration as a source in JSW [the Complete Works edition].” Virtanen (2017a, p. xii) states that the Schnirlin edition was published in 1929; the printed editions I have been able to obtain list a copyright year of 1933.

The International edition follows Schnirlin’s edition closely, replicating its page layout and engraving details. Wherever Schnirlin differs from the Complete Works in musical indications (for instance, crescendo/decrescendo markings, expressive indications such as tranquillo, and slur details), the International edition repeats these differences. Francescatti retains most of Schnirlin’s fingerings and bowings, but makes some changes.

For the passage shown in Figure 14, the editions differ significantly in their slurring, which customarily indicates or implies bowing for string instruments. Sibelius took care with the slurring of this counter-theme; for instance, he corrected the slur of m. 368 in his proof of the solo violin part. He also revised the slurring of the same figure in the oboe solo (and its doubling in the bassoon) on the engraver’s copy.34Virtanen (2014, p. 292). In the oboe and bassoon lines Sibelius changed single slurs over mm. 357–358 and 361-362 into the slurs found in the Complete Works edition. Yet he respected performers’ inclinations; in 1903 he wrote to Willy Burmester (for whom the concerto was originally intended):

I shall soon send you the Volin Concerto as an acceptable ‘Klavierauszug’ with a separate and clear main [ie., the violin] part. I can only dream how it might sound in your masterful hands. […] I shall write the slurs temporarily in lead so you can erase those you want (translated from Swedish in Virtanen 2014, p. viii).

As shown in Figure 14, the opening statement in the exposition falls under one slur in Sibelius’s hand. Schnirlin suggests an upbow in the middle of the slur, while Francescatti breaks the slur into three (downbow-upbow-downbow). The gesture leading to the Largamente falls under one slur for Sibelius and Schnirlin, and under two slurs for Francescatti. The recapitulation displays similar differences among editions: Francescatti breaks the single slur (m. 368 to the downbeat of m. 369) into two.35This slurring replicates Sibelius’s original slurring, which he revised in his proof of the solo violin part (Virtanen 2014, p. 292).

The upshot is that, in Francescatti’s edition, the solo violin entry looks gesturally quite similar from exposition to recapitulation: the only bowing difference is found in the first two sixteenth notes. In contrast, the exposition and recapitulation entries in Sibelius’s version look much more distinct—at least on paper. This visually distinct slurring, combined with the differences in rhythm mentioned earlier, as well as the differences in expressive indications (mp tranquillo in the exposition, versus p dolce in the recapitulation), give the impression that Sibelius intended the two versions of the theme to be characterized differently.

Short of an empirical study, however, it is impossible to draw conclusions as to how the editorial bowing details might affect interpretation of the secondary theme. What follows are observations from a brief sample, beginning with the three video performances with which we opened. Most bowing differences occur in the opening rise through the octave. Leonidas Kavakos (2015) does not bow according to any of these editions, but articulates the sixteenth notes in all cases with separate bows; his bowing is the same across exposition and recapitulation. Sarah Chang (2009) also retains bowing from exposition to recapitulation; she uses Francescatti’s exposition bowing in both cases.36Elina Vähälä (2015) bows similarly, but separates the x in the recapitulation, per Francescatti. Janine Jansen (2019) plays the ascending octave in the exposition with two bows rather than three, following Schnirlin, but reverses upbow and downbow (beginning with upbow rather than downbow). In the recapitulation she follows Francescatti.37Christian Ferras (1965) does the same, though he follows Schnirlin in the recapitulation (again beginning with upbow rather than downbow). Maxim Vengerov (1997) follows Schnirlin exactly through the passage shown in exposition and recapitulation; unlike the others, he also plays the sweeping upward gesture leading into the Largamente (and the corresponding spot in the recapitulation) in a single upbow. For the opening rise through the octave, Hilary Hahn (2022) also follows Schnirlin’s bowing in the exposition, and keeps the same bowing in the recapitulation, but plays the recapitulation much more slowly and introspectively. Anne-Sophie Mutter (2015) similarly uses the same Schnirlin bowing in both exposition and recapitulation; she plays both instances of the counter-theme dotted, but differentiates the recapitulation with a sweeter colour.

These bowing choices are many and varied, ranging from following Francescatti, to following Schnirlin, to adapting these two, or to creating one’s own bowing. Further, the similarity or difference in bowing between exposition and recapitulation does not correlate clearly with musical interpretation. With regard to this passage, some violinists who bow the exposition and recapitulation the same interpret them very similarly (Kavakos 2015, Chang 2009). Others who bow the two versions the same interpret them very differently (Mutter 2015, and especially Hahn 2022). Still others bow the exposition and recapitulation differently, but interpret them similarly (Jansen 2019, Vengerov 1997).

Meter as a Prism

Is the metric distinction then a mere notational artefact, or does it carry a deeper meaning? In performance, does it ultimately matter?

Meter becomes a prism through which we see Sibelius’s transformation of the secondary theme. The transformation concerns the theme in interaction with its formal and contrapuntal surroundings. It is not so much that the theme itself (the violin melody in S1.1) is in 6/4 in the exposition, and in 2 x 2/2 in the recapitulation, but that its context has changed entirely. In the exposition, the lengthy orchestral approach to the theme modulates to the new, foreign, 6/4 meter. Within the theme proper, in its brooding key of Db, the “rounder” rhythms of both theme and countertheme facilitate a compound duple feel. In the recapitulation, 2/2 reigns from the opening P theme, through the climactic orchestral transition, into the oboe solo introducing the secondary theme, and the solo violin entry picking up the same material. The theme proper then enters on the solid ground of the home meter, paced by the home tempo, and settled in the home key. Along with this homecoming to the idiomatic key of D, the violin soloist is paradoxically untethered from the notated and conducted meter, and free to soar. And here we see Sibelius’s mastery of temporal threads, spinning them out so that cross pulses, motives, and timbres interweave in a shifting tapestry. It is the hues of this tapestry that change for the secondary theme from exposition to recapitulation, and that are signaled by Sibelius’s metric puzzle.

Bibliography

Bowen, José (1993), “The History of Remembered Innovation. Tradition and its Role in the Relationship between Musical Works and their Performances,” Journal of Musicology, vol. 11, no 2, pp. 139–174.

Clarke, David (2019), “Music, Phenomenology, and the ‘Natural Attitude’. Analyzing Sibelius, Thinking with Husserl, Reflecting on Dennett,” in Ruth Herbert, David Clarke, and Eric Clarke (eds.), Music and Consciousness 2. Worlds, Practices, Modalities, Oxford, Oxford University Press, pp. 143–169.

Davis, Sir Colin, and Osmo Vänskä in Conversation with Daniel Grimley (2004), “Performing Sibelius,” in Daniel Grimley (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Sibelius, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, pp. 229–242.

Fantapié, Henri-Claude (1995), “The Oceanides. A Question of Tempo,” in Eero Tarasti (ed.), Proceedings from the First International Jean Sibelius Conference, Helsinki, Sibelius Academy, pp. 41–64.

Haapakoski, Martti (1996), “The Sibelius Concerto Still Holds a Record. Discography of the Recordings Released in the 1990s,” Finnish Music Quarterly, vol. 96, no 4, pp. 14–16.

Harper, Steven (2003), “Sibelius’s Progressive Impulse. Rhythm and Meter in The Bard,” in Matti Huttunen, Kari Kilpeläinen, and Veijo Murtomäki (eds.), Sibelius Forum II, Helsinki, Sibelius Academy, pp. 259–272.

Hepokoski, James (1993), Sibelius. Symphony No. 5, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Hepokoski, James, and Warren Darcy (2006), Elements of Sonata Theory, New York, Oxford University Press.

Howell, Tim (1998), “Sibelius’s Tapiola. Issues of Tonality and Timescale,” in Veijo Murtomäki, Kari Kilpeläinen, and Risto Väisänen (eds.), Sibelius Forum, Helsinki, Sibelius Academy, pp. 237–246.

Howell, Tim (2001), “Sibelius the Progressive,” in Timothy Jackson and Veijö Murtomäki (eds.) Sibelius Studies, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, pp. 35–57.

Kallio, Tapio (1998), “Metrical Structures in Sibelius’s Works,” in Veijo Murtomäki, Kari Kilpeläinen, and Risto Väisänen (eds.), Sibelius Forum, Helsinki, Sibelius Academy, pp. 276–281.

Kallio, Tapio (2001), “Meter in the Opening of the Second Symphony,” in Timothy Jackson and Veijö Murtomäki (eds.), Sibelius Studies, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, pp. 275–295.

Kallio, Tapio (2003), “Jean Sibelius’s Metrical Revisions,” in Matti Huttunen, Kari Kilpeläinen, and Veijo Murtomäki (eds.), Sibelius Forum II, Helsinki, Sibelius Academy, pp. 211–215.

Kane, Brian (2018), “Jazz, Mediation, Ontology,” Contemporary Music Review, vol. 37, no 5–6, pp. 507–528.

Laufer, Edward (1999), “On the First Movement of Sibelius’s Fourth Symphony. A Schenkerian View,” in Carl Schachter and Hedi Siegel (eds.), Schenker Studies 2, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, pp. 127–159.

Leong, Daphne (2025), “A Metric Puzzle in Sibelius’s Violin Concerto,” in Markus Mantere, Cecilia Oinas, and Inkeri Jaakkola (eds.), Encountering Music Analysis, Helsinki, Sibelius Academy, https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-329-390-8, pp. 291-334.

Leong, Daphne (2016), “Analysis and Performance, or wissen, können, kennen,” Music Theory Online, vol. 22, no 2.

Lowe, Bethany (2011), “Analysing Performances of Sibelius’s Fifth Symphony. The ‘One Movement or Two’ Debate and the Plurality of the Music Object,” Music Analysis, vol. 30, no 2–3, pp. 218–271.

Mäkelä, Tomi (1995), “The Sibelius Violin Concerto and its Dramatic Virtuosity. A Comparative Study,” in Proceedings from the First International Jean Sibelius Conference (1990), Helsinki, Sibelius Academy, pp. 118–133.

Mäkelä, Tomi (2011), Jean Sibelius, translated by Steven Lindberg (from Jean Sibelius: Poesie in der Luft, 2007), Woodbridge, Suffolk, Boydell Press.

Mirka, Danuta (2013), “Topics and Meter,” in Danuta Mirka (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Topic Theory, pp. 356–380.

Monelle, Raymond (2006), Musical Topic. Hunt, Military and Pastoral, Bloomington, Indiana University Press.

Pickett, David (2003), “The Fourth Symphony. Ending and Beginning in Complete Disaster,” in Matti Huttunen, Kari Kilpeläinen, and Veijo Murtomäki (eds.), Sibelius Forum II, Helsinki, Sibelius Academy, pp. 88–96.

Ramnarine, Tina (2020) Jean Sibelius’s Violin Concerto, New York, Oxford University Press.

Salmenhaara, Erkki (1996a), “The Violin Concerto,” in Glenda Goss (ed.), The Sibelius Companion, Westport, CT, Greenwood Press, pp. 103–119.

Salmenhaara, Erkki (1996b), Jean Sibelius Violin Concerto, Wilhelmshaven, Florian Noetzel Verlag.

Tawaststjerna, Erik (1976), “The Violin Concerto,” in Sibelius, vol. I. 1865–1905, translated by Robert Layton, Berkeley, University of California Press, pp. 270–294.

Tiilikainen, Jukka (2004), “The Genesis of the Violin Concerto,” in Daniel Grimley (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Sibelius, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 66–80, 248–249.

Tovey, Donald (1981[1935–1939]), “Sibelius Violin Concerto, Op. 47,” in Essays in Musical Analysis. Concertos and Choral Works, London, Oxford University Press, pp. 206–210.

Ueda, Yudai (2023), “A Conductor’s Guide to Jean Sibelius’s Symphony no 1 in E minor, Op. 39,” DMA diss., University of Arizona.

Väisälä, Olli (2017), “Sibelius’ Revision of the First Movement of the Violin Concerto. Removing Tonal Clichés, Strengthening Tonal Structure,” in Daniel Grimley, Tim Howell, Veijo Murtomäki, and Timo Virtanen (eds.), Jean Sibelius’s Legacy. Research on his 150th Anniversary, Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 376–400.

Väisänen, Risto (1998), “Problems in Performance Studies of Sibelius’s Orchestral Works,” Veijo Murtomäki, Kari Kilpeläinen, and Risto Väisänen (eds.), Sibelius Forum, Helsinki, Sibelius Academy, pp. 129–141.

Virtanen, Timo (2014), “Preface,” “Introduction,” and “Critical Commentary” to Sibelius 2014, pp. vi, viii–xviii, 258–301.

Virtanen, Timo (2017a), “Preface,” “Introduction,” and “Critical Commentary” to Sibelius 2017 , pp. vii, ix–xv, 91–109.

Virtanen, Timo (2017b), “Sibelius’ Sketches for the Violin Concerto,” in Daniel Grimley, Tim Howell, Veijo Murtomäki, and Timo Virtanen (eds.), Jean Sibelius’s Legacy. Research on his 150th Anniversary, Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 363–375.

Editions

Sibelius, Jean (2014), Concerto for Violin and Orchestra in D minor. Early Version [Op. 47/1904] and Op. 47. Jean Sibelius Complete Works, series II, vol. 1, edited by Timo Virtanen, Wiesbaden, Breitkopf & Härtel.

Sibelius, Jean (2017), Concerto for Violin and Orchestra in D minor, Op. 47. Piano Score. Early Version [Op. 47/1904]. Facsimiles and Reconstructions of the Piano Score. Jean Sibelius Complete Works, series II, vol. 1a, edited by Timo Virtanen, Wiesbaden, Breitkopf & Härtel.

Sibelius, Jean (1941, 1961), Concerto in D minor, Op. 47, for violin and piano, violin part edited by Zino Francescatti, piano reduction by Alexandre Gretchaninoff, New York, International Music Company.

Sibelius, Jean (1933), Violin-Konzert d-moll, Op. 47, violin part edited by Ossip Schnirlin, Berlin, Robert Lienau.

Performances and Recordings

Sibelius, Jean, Concerto for Violin and Orchestra in D minor, Op. 47.

Chang, Sarah (violin), Jaap van Zweden (conductor), Radio Filharmonisch Orkest, 2009, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gpS_u5RvMpM, accessed 20 September 2022.

Ferras, Christian (violin), Zubin Mehta (conductor), Orchestre National de ORTF, 1965, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=06OajNL1xeo, accessed 15 June 2024.

Hahn, Hilary (violin), Nicholas Collon (conductor), Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sVKRTb-Wp5g, accessed 15 June 2024.

Heifetz, Jascha (violin), Sir Thomas Beecham (conductor), London Philharmonic Orchestra, 1935, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-yvy9lS5DC4, accessed 15 June 2024.

Ignatius, Anja (violin), Armas Järnefelt (conductor), Städtisches Orchester Berlin, 1943, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gMuMKG2b6IE, accessed 3 October 2022.

Jansen, Janine (violin), Christoph Eschenbach (conductor), SWR Symphonieorchester, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iIafobNq-tU, accessed 20 September 2022.

Kavakos, Leonidas (violin), Simon Rattle (conductor), Berliner Philharmoniker, 2015, Europakonzert, Athens, https://www.digitalconcerthall.com/en/concert/20420, accessed 20 September 2022.

Mutter, Anne-Sophie (violin), Andris Nelsons (conductor), Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, 2015, https://watch.symphony.live/m/2Wanf5XG/mutter-plays-sibelius, accessed 15 June 2024.

Spivakovsky, Tossy (violin), Tauno Hannikainen (conductor), London Symphony Orchestra, 1959, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qJPoLz36Jhs, accessed 15 June 2024.

Vähälä, Elina (violin), Osmo Vänskä (conductor), Yomiuri Nippon Symphony Orchestra, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w–FaEaxdqQ, accessed 15 June 2024.

Vengerov, Maxim (violin), Daniel Barenboim (conductor), Chicago Symphony Orchestra, 1997, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pke4JHcY8UA, accessed 15 June 2024.

Sibelius, Jean, Concerto for Violin and Orchestra in D minor, [Op. 47/1904]: early version.

Leonidas Kavakos (violin), Osmo Vänskä (conductor), Lahti Symphony Orchestra, 1991, Grammofon AB BIS CD-500, Complete Sibelius 30, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EkPRQtJXaLw, accessed 21 September 2022.

Lecture-Recitals

“A Puzzle in Sibelius’s Violin Concerto”

Leong, Daphne and Ken Hamao, with Jessica Bodner (2024), Barwick Distinguished Colloquium Series, Harvard University.

Leong, Daphne with John Gilbert (2024), Texas Tech University, online.

Leong, Daphne and Jinjoo Cho, with Philipp Elssner (2023), International Conference Rhythm in Music since 1900, McGill University.

Leong, Daphne and Victor Avila Luvsangenden, with Edward Klorman (2023), Performance and Analysis Interest Group, Society for Music Theory and American Musicological Society Conference, Denver.

Leong, Daphne and Victor Avila Luvsangenden, with Daniel Moore (2023), University of Colorado Boulder.

Appendix

Performed Tempi: Methodology

Tempo was determined by syncing a metronome with passages of stable tempo, listed below. This informal method, rather than a more rigorous one, was chosen to obtain felt tempi, representative of key passages. The passages were chosen to avoid expressive timing at entries, cadences, and so on. Where performers expressively lengthened notes (at the ends of phrases, for instance), these pauses were ignored. (Such lingering is particularly marked at the ends of Ignatius’s [1943] phrases.)

Exposition:

S1.1: mm. 102-105 (Largamente)

Recapitulation:

| Article_RMO_12.2_Leong |

Attention : le logiciel Aperçu (preview) ne permet pas la lecture des fichiers sonores intégrés dans les fichiers pdf.

Citation

- Référence papier (pdf)

Daphne Leong, « Meter as a Prism. Interpreting a Theme in Sibelius’s Violin Concerto », Revue musicale OICRM, vol. 12, no 2, 2025, p. 179-199.

- Référence électronique

Daphne Leong, « Meter as a Prism. Interpreting a Theme in Sibelius’s Violin Concerto », Revue musicale OICRM, vol. 12, no 2, 2025, mis en ligne le 16 décembre 2025, https://revuemusicaleoicrm.org/rmo-vol12-n2/meter-as-a-prism-sibelius-violin-concerto/, consulté le…

Autrice

Daphne Leong, University of Colorado Boulder

Daphne Leong’s work, which focuses on rhythm, analysis and performance, and music since 1900, appears in her book, Performing Knowledge: Twentieth-Century Music in Analysis and Performance (Oxford University Press, 2019); in journals such as Journal of Music Theory, Perspectives of New Music, and Music Theory Online; and in edited collections. Leong is an active pianist and chamber musician, whose performances and recordings include premieres of current music. She has served as Vice President of the Society for Music Theory. In 2013 she received the Excellence in Teaching Award of the University of Colorado Boulder, where she is Professor of Music Theory.

Notes

| ↵1 | This essay is a companion to my 2025 article “A Metric Puzzle in Sibelius’s Violin Concerto.” The “Metric Puzzle” article provides a more extended treatment of the topic, and includes many aspects not discussed here (such as Sibelius’s sketches). The current essay adopts a modular multimedia format along with streamlined content that I hope will be useful for both performers and scholars. It also spends more time on practical issues, such as bowing.

The essay and article owe their existence to many people. Lina Bahn, violinist, first approached me with the puzzle. My visit to the Sibelius Academy in September 2022 at the kind invitation of Lauri Suurpåå motivated my further exploration; I thank Olli Väisälä, who thoughtfully pointed me to the concerto’s 1904 version. |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | Clarke (2019, pp. 160–163).

On the popularity of the concerto, see, for instance, Haapakoski 1996 who found that from 1990 to 1996 the Sibelius Violin Concerto was the fifth most recorded violin concerto, after Tchaikovsky, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, and Brahms. |

| ↵3 | On this transformational network view, see Leong (2016, p. 5). |

| ↵4 | Figure 2 can also be found at the end of this document. |

| ↵5 | See the bibliography for a list of our lecture-recitals and presentations. |

| ↵6 | Following Hepokoski and Darcy (2006), I use superscripts to indicate formal sections, here defined by thematic content and other elements of surface design, but not necessarily (unlike Hepokoski and Darcy) by cadences. For a detailed discussion of how Sibelius frequently avoids or obscures cadences in the concerto, see Väisälä (2017). |

| ↵7 | For a fuller discussion, as well as an overview of the voluminous literature on the Violin Concerto, see Leong 2025. |

| ↵8 | Virtanen (2017b, p. 374); Virtanen (2014, pp. ix, xii); Salmenhaara (1996a) and (1996b, pp. 40-42); see also the website of the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic: https://www.konserthuset.se/en/about-us/our-operation/festivals/grande-finale/liner-notes-and-curious-facts/violin-concerto/, accessed 12 July 2024. |

| ↵9 | For details, see Leong 2025. |

| ↵10 | See Virtanen (2014, p. x) for a summary of Flodin’s review. Among other criticisms, Flodin compares Sibelius’s concerto unfavorably to those by Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Bruch, Brahms, and Tchaikovsky. |

| ↵11 | “I shall withdraw the concerto; it will appear only after two years… The first movement shall be revised …” (letter to Axel Carpelan, 3 June 1904, translated in Virtanen 2017a, p. x). |

| ↵12 | “Das Violinconzert mache ich fast neu” (NA, SFA, file box 46. n.d., quoted in Virtanen 2014, pp. x, xv). |

| ↵13 | The first statement (26 Jan 1905) is cited in Virtanen (2017a, p. x); the second (April 1905) in Virtanen (2014, p. x). |

| ↵14 | This cadenza (which does not appear in 1905) is often called a “second” cadenza, falling after the mini-cadenza of the exposition and the first cadenza comprising the sonata form’s development section. |

| ↵15 | In 1943 Sibelius even told his son-in-law, the conductor Jussi Jalas: “the accompaniment of the violin concerto shall be rehearsed like a symphony”—though in 1930 he worried about the orchestra being too heavy. “I would still like to alter the orchestral accompaniment. It is too heavy. Like a symphony.” (The first statement is recorded in Jalas’s 1943 notes, NA, SFA, file box 1; the latter is found in a letter to Sibelius’s publisher Robert Lienau. Both are cited in Virtanen 2014, pp. xiii, xvii.) |

| ↵16 | Mäkelä (1995) points out the unusual heft of the orchestra, which features three trombones. |

| ↵17 | The seam between TRP and S seems to have caused Sibelius trouble initially (see Leong 2025). |

| ↵18 | Mirka 2013 traces the developing independence of notated and actual meters (which she calls “composed meters”) in Classical practice, showing how their decoupling facilitated stylistic cross-references. Such cross-references certainly feature in Sibelius’s secondary theme. For the double measure, see Mirka (2013, p. 365 ff.). |

| ↵19 | See Allanbrook 1983, p. 22 and Mirka 2013, pp. 360–361.

In the 1904 exposition, TRS is notated in 3/2 half notes, with w = w . , equivalent to the double measure in the 1905 recapitulation. In 1905, Sibelius saves this more weighty version for the recapitulation. |

| ↵20 | For the recapitulation, tempi for both the notated pulse ( h ) and the double measure’s pulse ( w ) are indicated.

See the Appendix for a description of the methodology used to determine performed tempo. Leong 2025 examines performed tempi at other key points. |

| ↵21 | Only Chang/vanZweden (2009) take the recapitulatory secondary theme faster than the expository one. |

| ↵22 | See Mäkelä (2011, pp. 58–62) for a sampling of such comments taken from Sibelius’s letters. |

| ↵23 | This statement, originally in German and quoted from Mäkelä (2011, p. 62), is taken from a letter draft in National Archive Box 36. |

| ↵24 | Heifetz/Beecham begin the movement at h = 70; the other six performances begin at tempi ranging from h = 50 to h = 59. |

| ↵25 | Well-known violin concertos in D major include those by Beethoven (Op. 61), Brahms (Op. 77), and Tchaikovsky (Op. 35). |

| ↵26 | “Turbulent” is Jinjoo Cho’s description, in a very funny discussion of the differences between playing in Db and in D (Leong and Cho 2023 lecture-recital). |

| ↵27 | I thank Annika Bowers for this suggestion. |

| ↵28 | Sibelius’s autograph piano score shows that, in the exposition, this passage was originally dotted in the solo violin—but not in the orchestra. See Facsimile III in Virtanen (2017a, p. 79). |

| ↵29 | Arabic numbers again represent numbers of measures in the exposition, and numbers of double measures in the recapitulation. |

| ↵30 | Tenuto markings occur later in the exposition, when its theme returns to major. |

| ↵31 | The move to F major (rather than D major) also allows Sibelius to move easily to the Closing theme in the desired D-minor key; in the exposition the corresponding relationship was Db major to Bb minor. |

| ↵32 | The 1905 Lienau edition, not shown here, was the source for the 1933 Schnirlin edition. For this passage, the 1905 edition is the same as in 1933 (minus the bowing and fingering indications) but for one detail: in 1905, the initial crescendo marking begins before the barline. |

| ↵33 | Virtanen (2017a, pp. xii, xv) provides a detailed account of Lienau’s correspondence with Sibelius on the topic of the Schnirlin edition. Virtanen (2017a, p. 93) writes, “Whether Sibelius applied his mind to the Schnirlin edition and accepted the additions is highly questionable, even unlikely. Although the edition was printed during the composer’s lifetime and has been widely used, it has remained without further consideration as a source in JSW [the Complete Works edition].” Virtanen (2017a, p. xii) states that the Schnirlin edition was published in 1929; the printed editions I have been able to obtain list a copyright year of 1933. |

| ↵34 | Virtanen (2014, p. 292). In the oboe and bassoon lines Sibelius changed single slurs over mm. 357–358 and 361-362 into the slurs found in the Complete Works edition. |

| ↵35 | This slurring replicates Sibelius’s original slurring, which he revised in his proof of the solo violin part (Virtanen 2014, p. 292). |

| ↵36 | Elina Vähälä (2015) bows similarly, but separates the x in the recapitulation, per Francescatti. |

| ↵37 | Christian Ferras (1965) does the same, though he follows Schnirlin in the recapitulation (again beginning with upbow rather than downbow). |