Rhythmic Self-Entrainment. A Panacea

Jacqueline Leclair

| PDF | CITATION | AUTHOR |

Abstract

This article proposes rhythmic self-entrainment (RSE)—commonly referred to as “subdividing”—as a possible solution for the types of malaise many post-secondary music students experience during daily music practice: frustration, mindlessness, excessive stress, and anxiety. While RSE is traditionally taught to help students improve musically, this article shows how it could also be implemented as an effective method for improving mental health. Considering the context of rising mental health crises that affect post-secondary students worldwide, improvements in music student mental health are urgently needed. Necessarily speculative in nature, this article examines RSE through the lenses of various musical, psychological, and philosophical disciplines, and explains how RSE offers the potential to profoundly improve music student mental health.

Keywords: music pedagogy; music student mental health; rhythm; rhythmic self-entrainment; subdividing.

Résumé

Cet article propose l’auto-entraînement rythmique (AER) – communément appelé « subdivision » – comme solution possible aux désagréments que vivent de nombreux étudiants en musique de niveau postsecondaire dans leur pratique journalière de la musique : frustration, manque de concentration, stress excessif, anxiété. Il explique comment l’AER peut non seulement être enseigné aux élèves afin de les aider à améliorer leurs compétences musicales, mais également leur fournir un moyen efficace d’améliorer leur santé mentale. L’amélioration de la santé mentale des étudiants en musique est une question pressante, alors que les problèmes de santé mentale affectant les élèves de niveau postsecondaire sont en croissance dans le monde entier. Cet article de nature forcément spéculative aborde l’AER par le prisme de différentes disciplines musicales, psychologiques et philosophiques et explique comment il peut améliorer de manière significative la santé mentale des étudiants en musique.

Mots clés : auto-entraînement rythmique ; pédagogie de la musique ; rythme ; santé mentale des étudiants en musique ; subdivision.

Preface

This article proposes rhythmic self-entrainment—commonly referred to as “subdividing”—as a possible solution for the types of malaise many post-secondary music students experience during daily music practice. The author, an internationally known oboist and pedagogue, has for many years supported the wellbeing of music students and launched various initiatives to help cultivate better mental and physical health during their studies and careers. This article will define rhythmic self-entrainment, cite expert musicians on how they use it, and connect it to various aspects of wellbeing, before offering conclusions and paths forward.

Introduction

Mental health challenges in post-secondary students have been increasing for years. Abrams (2022, p. 60) states that in a “national survey, almost three-quarters of students reported moderate or severe psychological distress.” According to Mowreader (2024) “Recent data from Inside Higher Ed’s 2024 Student Voice survey of 5,025 undergraduates, conducted by Generation Lab in May, found 2 in 5 students say their mental health is impacting their ability to focus, learn, and perform academically ‘a great deal,’ and 1 in 10 students rates their mental health as ‘poor.’” Postsecondary music students, in addition to the academic and social pressures faced by their peers, experience the stress of auditions, highly competitive environments, music performance anxiety, and the need to perform to a high degree of accuracy on demand, as well as future job market and financial uncertainty. Writing about the mental health of postsecondary music students, Kegelaers, Schuijer, and Oudejans find that:

The prevalence of symptoms of mental health issues (i.e., depression/anxiety) was relatively high among the participants of the present study, varying between 39.3% for professional musicians and 61.1% for music students. (Kegelaers, Schuijer, and Oudejans 2021, pp. 1273-1284)

In my capacity as a university music professor, I have often wondered if a key to wellbeing could be found in music students’ daily schedules. Students are typically required to practice alone for hours every day. They consistently report experiencing frustration, mindlessness, anxiety, and excessive stress during these hours of individual practice. This kind of distress negatively impacts not only their musical experiences, but also their wellbeing and quality of life overall. I have come to believe that student wellbeing can be improved by improving students’ practice; and the key to improving their practice lies in the ways students conceptualize rhythm.

Since 2009, I have contemplated music student mental health in the context of my graduate seminar, “Musician Wellbeing.” In the past few years, it has become increasingly clear to me that most students have not learned how to practice. Consequently, the techniques they use to learn music and improve their skills tend to be inefficient. This is a profound weakness of music pedagogy and not uncommon, even at high levels of achievement. Performance psychologist and musician Noa Kageyama notes that despite having excellent violin instruction throughout his life and finishing two degrees in violin performance at the Juilliard School, it took him nearly twenty years to figure out how to practice properly (Gebrian 2024, p. xi). It seems likely that lacking knowledge of how to practice efficiently, safely, and productively is a significant source of music students’ mental health struggles.

Please watch and listen to these three renditions of the first nine measures of the oboe part of Gordon Jacob’s Oboe Quartet which will be explained below. What differences do you perceive among the three renditions?

Media 1: Version 1 of the author playing the Jacob excerpt.

Media 2: Version 2 of the author playing the Jacob excerpt.

Media 3: Version 3 of the author playing the Jacob excerpt.

Rhythmic Self-Entrainment

Rhythmic self-entrainment (RSE), commonly referred to as “subdividing,” is arguably the most important aspect of music making for musicians of all instruments, voices, and musical styles. Pedagogically, subdividing is normally framed as the best method for improving rhythmic accuracy. For instance, according to an online tutorial on music fundamentals:

“Subdividing” refers to dividing the beat, most often silently, into smaller units […] usually […] eighth or sixteenth notes. The ability to subdivide while performing music ensures rhythmic accuracy and is an important skill that all musicians need to develop. (Ewell and Schmidt-Jones 2013)

The present article, however, argues that music students can achieve a wide range of improvements, not only to their musical skills, but also to their wellbeing, by routinely focusing more detailed attention on RSE with the smallest rhythmic units during daily practice. While “subdividing” is the more common term, I am using “rhythmic self-entrainment” to connote a broader and deeper definition of the technique.

“Entrainment” refers to the process by which two or more systems synchronize in any number of realms, such as nature, machines, people, and music. Musical rhythmic entrainment can be as simple as a person tapping their toe to music, or it can involve playing a musical instrument in sync with a metronome or another musician. Rhythmic self-entrainment occurs when a musician establishes a rhythmic signal (tempo) in their mind and synchronizes all other mental activity while playing or singing with that self-generated, continuous rhythmic signal/pulse. As we will see, below, RSE is a deep, embodied, and nuanced element of music making. The term avoids the negative and superficial connotations that the term “subdividing” can carry and instead conveys broader and deeper meaning. While some kinds of musical entrainment have been studied, such as human subjects rhythmically entraining with metronomes, there is very little research to date on musical self-entrainment.

Since music students must practice for hours in solitude most days—and since they often report experiencing distress in this setting—it makes sense to take their practice sessions as the best window of opportunity to improve their wellbeing. As I will explain in detail below, this can be accomplished by making a strategic change to their practice technique: increasing RSE with the smallest rhythmic units, which would mitigate many of students’ common complaints.

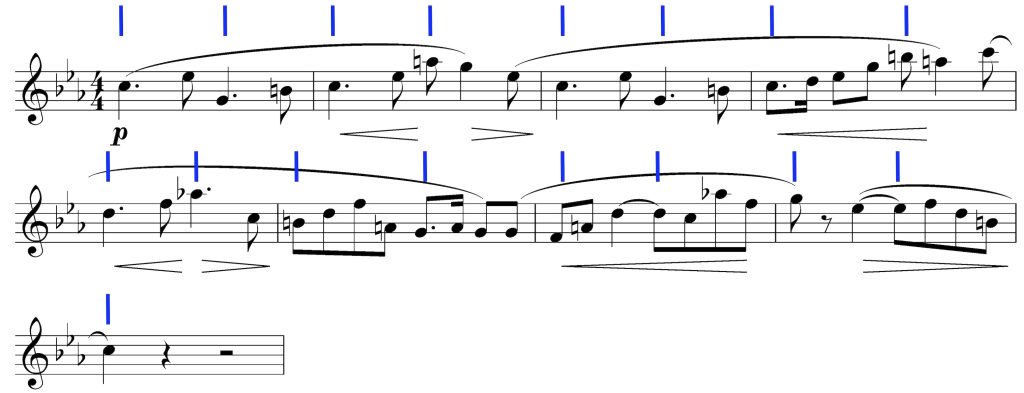

To demonstrate RSE, I recorded the first nine measures of the oboe part of Gordon Jacob’s Oboe Quartet (1938) in three different ways as I introduced, above:

1) RSE with half notes (two relatively slow pulses per measure):

Figure 1: Gordon Jacob, Oboe Quartet for Oboe and Strings, mm. 1-9 of the oboe part.

2) RSE with eighth notes:

Figure 2: Jacob, Oboe Quartet, mm. 1-9 of the oboe part, conceived in eighth notes.

and 3) RSE with sixteenth notes:

Figure 3: Jacob, Oboe Quartet, mm. 1-9 of the oboe part, conceived in sixteenth notes.

To be as fair as possible during these demonstrations, I did not practice performing the excerpt with the three kinds of RSE. I recorded the videos quickly in my work studio, and the videos are raw and unedited. My goal was to display very frankly any differences we might be able to perceive by my playing the excerpt with the three different kinds of RSE. When I viewed the videos afterward, I was surprised to see how different my body use was in the three videos: very little physical movement while using RSE with half notes, distinctly more movement while using RSE with eighth notes, and even livelier movement while entraining with sixteenth notes. I had been unaware of those differences in my physical movements while I recorded the three versions. As I performed the excerpt using RSE with half notes, I felt unengaged and unable to play with the nuance and expression I normally would, despite doing my best to do so. When I performed the excerpt using RSE with the eighth-note pulse, I felt distinctly more engaged, but still limited in terms of having the freedom and ability to play musically. Only when I performed the excerpt using RSE with the 16th notes did I feel fully engaged and able to play more freely and musically.

As I hope these recorded examples exemplify, improved rhythmic accuracy is only the tip of the iceberg of the potential benefits subdividing (RSE) can provide a musician. RSE is essential to all aspects of music-making.

Personal Background with RSE

When I was 16 years old and in a lesson with my oboe teacher, Patricia Stenberg (Sarasota, Florida), she had me put the metronome on at 60 bpm and loudly clap four times per beat with no accents. I did so, and then she said, “Tell me your phone number.” Initially, I couldn’t imagine speaking freely as I maintained the steady clapping. But that was the assignment, and over time I gradually learned to speak extemporaneously while maintaining loud, steady clapping in sync with the metronome. Ms. Stenberg also had me prepare and perform for her various exercises from a rhythm book by Larry Teal that I will describe in detail, below. I had to do those rhythm exercises in many of my lessons.

I can appreciate in hindsight that this early rhythm training provided me a strong background in RSE and must have helped me benefit from musicianship classes later during my three post-secondary degrees. Two classes during my doctoral study taught by Professors Arthur Weisberg and Samuel Baron respectively, delved extensively into complex rhythm skills, doubtlessly further enhancing my RSE and other rhythmic skills. (I remember arriving late to a class with Prof. Baron, and as I entered the room he said, “Okay, Jackie, perform for us eleven over seven” laying down a 7/8 pattern over which I had to speak 11 even values.) Throughout my 35 years as a professional musician, I have performed and recorded a great deal of contemporary music, much of which required unusual and complex rhythmic understanding and skills by composers such as Luciano Berio, Ursula Mamlok, Iannis Xenakis, Roger Reynolds, György Ligeti, George Benjamin, Brian Ferneyhough, Tōru Takemitsu, and countless others.

Having spent most of my life using RSE as a foundational element of my music-making and now perceiving music students suffering from what I understand to be their insufficient understanding and use of RSE, I feel impelled to do whatever I can to help. I am not alone in this as we will see in the following paragraphs.

Perspectives from Notable Professionals

In this section, I quote experienced and distinguished musicians and pedagogues, explaining their understanding of RSE and its essential role in music and wellbeing. In a 2018 interview, Noa Kageyama (bulletproofmusician.com) interviewed the legendary horn player and pedagogue Julie Landsman about RSE, which she refers to as “subdividing.” She clearly explains her understanding of how foundational subdividing is to her musicianship:

I subdivide 100% of the time, whether it’s while teaching a student, whether it’s while practicing […] and absolutely when I perform, just about every entrance for sure, and while playing, very diligently. So yes, subdivision is the glue that holds together all of the technical aspects of my playing so that my music making is free […] It gives you the freedom and the flexibility to mess with the time but keep incredible structure within the time […] It’s a pulse inside of my tone that isn’t an audible pulse to anybody listening, but it’s a felt sense, kinesthetically. It’s not a mental practice, but it’s a very physically based feel of time. (Landsman 2018)

Landsman’s point that RSE is not merely mental, but is an embodied, kinesthetic rhythmic practice involving the entire body and subconscious mind, is key information that many miss. RSE must be fully embodied and integrated, physically and mentally. It is an intrinsic part of musicianship, as fundamental as any other musical skill, such as good intonation. A superficial, purely mental awareness of subdivisions does not provide much benefit at all.

In another interview, Kageyama spoke with the violist Steven Tenenbom, who was for many years a member of the Orion String Quartet. In their interview, “Rhythm, phrasing, and the life within each note,” Kageyama relates his own experience as a student when he gradually began to understand the depth and importance of subdividing:

About 30 years ago now, I think it might have been the slow movement of the Schubert B-flat Piano Trio that we were working on where [Leon Fleisher] asked us to subdivide, and we very diligently subdivided, and then he stopped us again to say that now it sounded like we were playing with a metronome, and that wasn’t at all the point of subdividing […] The idea was to be able to play around with time and play more freely and take more time even, but in a way that didn’t mean distorting things randomly […] I think we’ve heard this message from all our teachers at some point or another […] it took a few years for it to really kind of make sense to me, but when it did, it really was transformative, musically and even technically […] whether it’s bow distribution or dynamics […] It changed my experience mentally as well in terms of my experience performing. It gave me something very tangible and meaningful to focus on when I was playing, and I was much more present and engaged in each moment and it felt more like I was creating in each moment. (Kageyama 2024)

Tenenbom replies, sharing similar experiences he had as a student learning the nuances of optimal subdividing as well as his current thoughts on the subject:

I remember something with Leon Fleisher […] in the C minor Brahms Piano Quartet, Opus 60 […] There’s that beautiful slow movement that starts with a cello solo. And he had the cellist do the same thing where he said […] take the smallest value, in that music that you’re playing, which in that case was a sixteenth note, and then play or sing the phrase playing all the sixteenth notes. And I guess the point he was getting at is that the change of sound on long notes would be best illustrated if you actually heard the subdivisions in it. And I think when you […] become more sensitive to that, you don’t have to play separate notes […] I know, we’re probably talking about a rhythmic thing as well, but in terms of phrasing, longer notes are actually made up of many small pieces […] And that probably gets to the counting part, because if you line up and you coordinate with the change of sound on a note, whether it be softening, intensifying, changing color, all those things, then you’re in tune with the subdivisions, and then your rhythm becomes quite naturally attached to the musical effects you’re trying to make. (Kageyama 2024b)

Judith Eissenberg, Professor of Music at Boston Conservatory at Berklee since 2001, has coached string quartets and other chamber ensembles throughout her career. She was a founding member and the second violinist of the Lydian String Quartet for more than forty years, retiring in 2022. I spoke with her in February 2024; and her thoughts on RSE resonate with those from Fleisher, Kageyama, and Tenenbom:

I urge the string quartets I coach to think of the metronome as a fifth colleague, another member of the group with whom to have a conversation. This colleague provides a foundation on which they can develop musical flexibility […] The very rigidity of their colleague—the metronome—invites an improvisational attitude from those who relate to it.The purpose of using the metronome is to tap into the inevitability of time, developing musical freedom and creativity in relationship to the beats. This is, of course, very like our own lives, as the seconds, minutes, and years pass. There is a tension between the measured, steady, relentless flow of time and the human expression of just how we feel about our passing through it. This is music.

I tell my quartets that if they begin to play metronomically, they are turning down the offer to play with the particular freedom of someone who knows the limits and still chooses to push them. (J. Eissenberg 2024)1 J. Eissenberg, personal communication, July 26, 2024.

Daniel Kurganov is a concert violinist who offers many outstanding pedagogical videos online. In his video, “Top 10 Tips for Rhythm & Pulse (Part 1),” he speaks about the distinction between superficial approaches to subdividing and a more internalized, physical approach:

To improve your […] internal sense of rhythm can be a bit tricky. Many of us don’t feel the internal rhythm of our motions; and we are rather trying to superimpose our playing on a sort of metronome that is going on inside of our heads. What I will show you is how to develop that sense of rhythmic intuition so that rhythm […] [is a] concrete and integrated sense of physical cohesion that is also vital for crafting interesting musical ideas such as adding rubato or taking various other liberties in your playing […] You’re not imagining the beat and then trying to stick to it. Rather, your motions themselves are the beat; and they will persist after the metronome is turned off. (Kurganov 2020a)

In his “Top 10 Tips for Rhythm & Pulse (Part 2),” tip number nine is: “Try to feel the rhythm or the pulse of a piece by allowing it to move your body, this could mean anything from swaying back and forth… to even a more active dancing motion” (Kurganov 2020b).

Erik Ralske is principal horn of the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra in New York City. In an interview with Noa Kageyama, “On Developing a Stronger Rhythmic Pulse” he shares some of his concepts about subdividing and its key role in his success as a confident and consistent performer:

Subdivision is what propels the energy through a phrase […] So if you take each of those subdivisions as little points […] [they] become like stepping stones up and down the hills of the phrase that I can latch onto. [The subdivisions] provide me with many good things […] I’ve attached the emotional content of the phrase to each subdivision. I’m moving in the direction I want to, and it’s controlled. It’s like having your hands on the steering wheel at every moment. If you want them to take a little bit of a right-hand turn, how far? Is it a sharp turn? Is it a gradual turn? And I can steer it back in the [right] direction. And with that comes better technique […] In order to connect point one to point two, it has to be moving […] in a linear fashion. So, [subdividing creates] better technique, more expression, and perfect rhythm.

And the last thing addresses the mental […] if you’re really concentrating on rhythm, it’s what brings you into the zone […] focused on the present tense only… And past and future disappear [which] are where anxiety lives. But [subdividing] keeps you moving […] So hopefully in a performance […] you’re following the blueprint you’ve laid out. And then, fear, it might still be there on some level, but you just have to follow your own blueprint.

I “sing my song” the way I think it should be sung and […] in order to do that successfully, I have to be engaged on an organic level of subdivision and living in the moment. (Kageyama 2024a)

Ralske published a short article on subdividing, “Five Essential Reasons to Subdivide,” that reinforces his thoughts in the interview above. The five reasons are 1) perfect rhythmic control 2) clearer and more expressive phrasing 3) better air flow throughout phrases 4) fewer technical mistakes, and 5) a remedy for performance anxiety. He explains that using RSE reduces performance anxiety because it creates a “deeper level of concentration and feeling of engagement while you play […] subdivision by subdivision” (Ralske 2021). A music student who is experiencing deeper concentration and greater engagement with the music while playing is likely to feel less anxiety and therefore to experience improved mental health in general.

It is essential to highlight that all the artists above describe RSE (subdividing) as, in their words, physical, kinesthetic, a pulse inside my tone, physically based, tangible, and organic. Landsman calls it “the glue that holds together all of the technical aspects of my playing so that my music making is free.” They emphasize that detailed, engaged RSE makes creativity, imagination, freedom, and beautiful phrasing possible. Indeed, it enables the musician to improve all aspects of technique, including performance confidence. In other words, RSE is essential to optimal music making.

All of this is traditional advice that teachers share primarily for musical reasons, to help students of all instruments, voices, and musical styles enhance their musicianship. The present article extends the discussion to recognize that RSE can also reduce or eliminate much of the psychological and emotional distress many music students experience during practice.

Recent Resources

Three striking books about the science of music practice have been published recently: Molly Gebrian’s Learn Faster, Perform Better. A Musician’s Guide to the Neuroscience of Practicing (2024), Hans Jørgen Jensen and Oleksander Mycyk’s PracticeMind for Everyone (2023), and Kristian Steenstrup’s Deep Practice, Peak Performance. The Science of Musical Learning (2023). While there are many books that discuss music practice, these books identify common practice mistakes and explain in detail how to practice safely and efficiently, all bolstered by recent neurological research and other sciences. The virtually simultaneous publication of these three books represents a turning point in our understanding of music practice and performance.

The Jensen/Mycyk book includes chapters on “Rhythm Training” and “Metronome.” While the authors discuss “entrainment,” rather than “self-entrainment,” their book offers excellent, detailed advice about internal rhythmic pulse, eurythmics, rhythmic character, and singing and dancing with the music one is learning. The final short paragraph, “Subdivide the Beats,” concludes, “feeling the subdivisions creates an incredibly powerful inner rhythmic pulse that helps create a long expressive line when required” (Jensen and Mycyk 2023, p. 104).

In Chapter 14 of her book, “Improving Rhythm and Tempo,” Gebrian explains details of how to develop improved senses of rhythm and pulse. Her advice resonates with the advice in Kurganov’s videos; and she includes explanations of the science behind the advice. Both Gebrian and Kurganov recommend subdividing and provide detailed examples of how to do so in various ways while practicing. Both recommend using the app Time Guru Metronome with which one can randomize patterns as well as silence a certain percentage of the metronome clicks randomly.

Finally, both Gebrian and Kurganov recommend moving the entire body in ways that match the rhythmic structure of the music; Gebrian gives a scientific explanation for why physical movement improves rhythm. Her chapter concludes: “developing a strong internal sense of pulse is the framework on which everything else rests” (Gebrian 2024, p. 180). This resonates with the preceding interviews that emphasize the need for RSE to be internal, physically felt, kinesthetic, and tangible. It also resonates with the clear differences in my own body movement in the videos demonstrating the three kinds of RSE.

Example of RSE Pedagogy

I would like to share an illustrative story about an oboe lesson I taught approximately fourteen years ago, one of many such experiences I have had as a pedagogue. I offer it as a real-world example of guiding students to develop RSE for musical reasons.

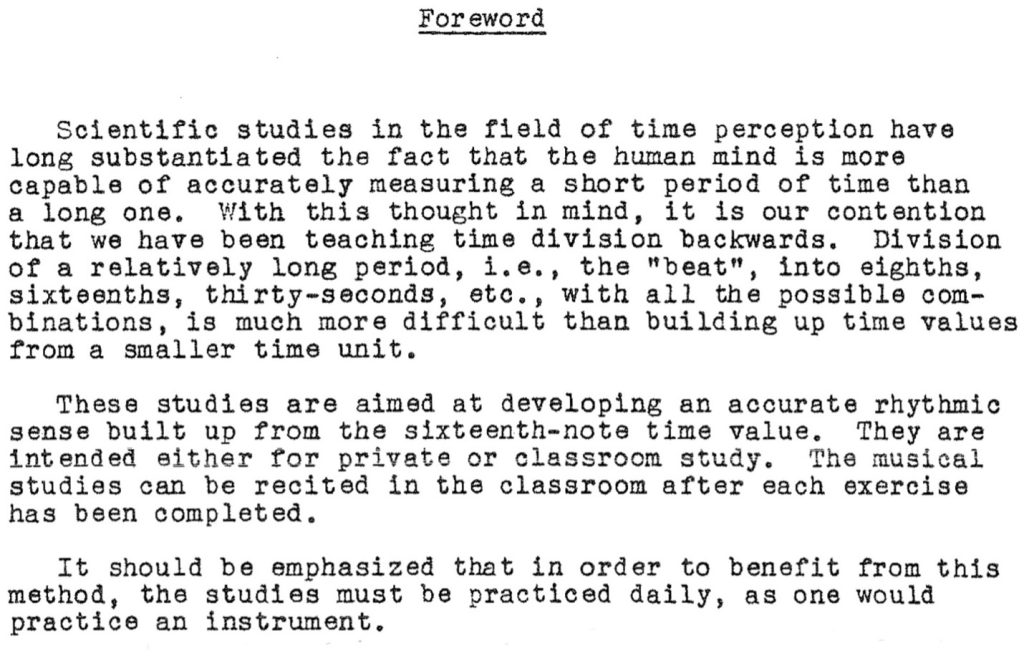

“Mary” was an undergraduate oboe student. I was working with her on rhythm during a lesson at Bowling Green State University, using the Larry Teal book Studies in Time Division. We were doing an exercise with Mary speaking phonemes for the rhythms of a short etude while loudly clapping the sixteenth notes in time with a metronome set to 54 bpm representing the quarter note. It can be challenging to maintain accuracy and consistency: One-ta-tay-tuh, Two-ta-tay-tuh, etc. with loud, even clapping (and no accents on the metronome click). One speaks only the phonemes that correspond to the etude’s notated rhythms. The loud, unaccented clapping represents the sixteenth notes one self-entrains with later, mentally and physically, while playing the etude.

Figure 4: Example from Teal (1955, p. 9).

I demonstrate this exercise in a short video.

Video 1: The author demonstrating the Larry Teal etude skills.

Teal explains the purpose of his book:

Figure 5: Example from Teal (1955, para. 1-3).

Once Mary was able to clap and speak accurately and consistently, it was time for her to pick up her oboe and play the etude with the goal of maintaining the same rhythmic thinking (RSE) throughout. However, she lapsed back into imprecise rhythm. Smiling, we acknowledged the lapse and went back to clapping/speaking the rhythm of the melody. Once again, she achieved accurate clapping and speaking and then picked up her oboe to play the etude. This time, she was successful in maintaining the rhythm as she played. When she finished, I said, “Did you notice that just now, when you played the etude with really good rhythm, you were much better in tune and more musically convincing than the first time?” She was surprised to realize that this was true. When she had played with poor rhythm, her intonation had also been very sharp, and the phrasing stilted. But when she used RSE, her intonation was much better and the phrasing was convincing. She had been unaware of these improvements until I drew her attention to them.

This is a vivid example of the benefits RSE offers, as well as the role pedagogues can play in helping students gain them. RSE was the root issue. Her poor phrasing and intonation were only symptoms. Trying to improve her phrasing and intonation without addressing RSE would not have been successful. Once she established RSE, her intonation and phrasing improved naturally. While there are many factors that can affect how well a musician plays a certain etude, during that lesson, Mary and I understood RSE to be the main determining element. This aligns with countless similar experiences I have had as a pedagogue.

Obstacles to Teaching and Learning RSE

My sense is that highly skilled and experienced musicians do use RSE and do their best to encourage their students to do so as well, as we’ve seen from the musicians and authors above. Yet RSE can be elusive as a pedagogical topic. Compared to other aspects of playing and singing, RSE is difficult to evaluate in a student. The teacher has only secondary evidence to go by, which can be unreliable and inexact. Thus, most teachers find it easier to discuss more clearly identifiable topics with students such as intonation, dynamics, physical techniques, style, and the more objective aspects of rhythm. Also, it is important to remember that even students who do receive clear and accurate advice about RSE may take years to truly understand and implement it properly, as Kageyama pointed out.

The impossibility of perceiving RSE directly is a primary obstacle for teachers and students. Following the past two years of my research on these topics, I have been making increased efforts to share RSE with students, to encourage them to understand and use it well. Typically, students seem to find it challenging to pick up RSE concepts and skills and to incorporate them into their existing mental and physical technique; and I believe this is because RSE cannot be observed directly, so one must discuss and access it through only indirect methods as we have already seen (the Teal clapping techniques, and articulating each sixteenth note, for example). The hope is that students can pick up on kinesthetic and engaged RSE by using such techniques and advice and eventually incorporate RSE into their fundamental technique.

Another obstacle to learning embodied, internalized RSE is the pervasiveness of misunderstandings about and biases against “subdividing.” Many think of it as only a remedial exercise to fix poor rhythm. A professor advising a student to “subdivide” often gives the impression that the “real” notes are the ones on the page and mental “subdivisions” are only a theoretical, remedial construct. Even if that is not the professor’s understanding or intent, students often receive that message. “Subdividing” only mentally, without sufficient embodiment and engagement, can feel like a tedious musical exercise, a necessary evil used to improve rhythmic deficiencies. These misunderstandings and biases prevent students from recognizing RSE as the foundational element of optimal musicianship that it truly is. These misunderstandings and biases must be overcome for students to learn and embrace RSE, and to benefit from all that it offers.

While the Teal book certainly can offer benefits to students, I suspect that the book has fallen out of use. Furthermore, the 24-page book includes only basic rhythmic examples from simple time and compound time signatures. Teal writes in the summary:

The possible combinations are endless, and the aim in this method has been to include the basic patterns only. It is hoped that with these fundamentals the students will be able to analyze and correctly interpret the more complicated patterns […] It is hoped that the student will apply this type of counting in his other musical activity until accurate time spacing becomes second nature. (Teal p. 24)

The Robert Starer book, “Rhythmic Training” (1969) is, to the best of my knowledge, the most widely used rhythm tutorial in North American post-secondary programs. In the preface, Starer writes:

The ability to transform visual symbols of rhythmic notation into time-dividing sounds is an acquired skill. It involves the coordination of physical, psychological, and musical factors and cannot, therefore be accomplished by the simple act of comprehension. This book represents an attempt to develop and train the ability to read and perform musical rhythms accurately. (Starer 1969)2 See Preface, paragraph 1.

The Starer text is over 55 years old, has 83 pages, includes only rhythmic materials that were basic at that time, and is entirely based on meter. He states that his goal is to help develop accurate rhythm, which, as we have seen, is only a small aspect of RSE. The text focuses on “dividing the beat” into subdivisions—which implies a mental exercise—and refers only rarely to “pulse” which would suggest more kinetic and organic engagement. Moreover, unlike Teal, Starer does not mention that his book covers only basic material and that the student would need to internalize the rhythmic training offered and then extend it to more complex challenges.

The contrast is clear between the limited, basic rhythmic instruction in North American post-secondary music curricula and the nuanced, embodied, fully integrated, and highly musical RSE that we have heard about from the quoted musicians and pedagogues. So, we can see that North American post-secondary music schools, in general, provide inadequate rhythmic training for students. This goes a long way toward explaining music students’ widespread lack of sufficient RSE.

The 2013 rhythmic training book by José Eduardo Gramani, Rítmica, is widely used in Brazilian music post-secondary schools and provides a useful, contrasting example. The Introduction includes, “The objective of this work is to try to bring musical rhythm closer to its full realization, to try to situate rhythm as a truly musical element and not just an arithmetic one.”3 “O objetivo deste trabalho é tentar trazer o ritmo musical mais próximo de sua realização total, tentar colocar o ritmo realmente como um elemento MUSICAL e não somente aritmético.” Translated by André Januário. (Gramani 2013, Introduction para. 2). Most of the rhythmic exercises are independent of time signature, and they stress rhythmic relationships of many varieties and complexities. Notably, compared to Teal’s 24 pages and Starer’s 83 pages, the Gramani book has 204 pages.

Professor André Januário, a bassoonist who earned his undergraduate degree in Rio de Janeiro in 2013, wrote to me that, during his studies, Brazilian schools required “Music Perception” courses that used the Gramani book and focused on only rhythmic and aural skills training (no music theory), commenting:

We were required to take four semesters of Music Perception, which were on Wednesdays and Fridays for one hour and 50 minutes. It was a lot […] The main idea that all teachers and professors emphasized was that we should be able to read any music only using subdivisions. One professor always said the goal was not to rely on the time signature […] The goal was to develop “internal pulse.”

Based on my experience, I would say that the Brazilian system is way ahead of the USA. I taught music theory in two state universities in the United States, and when I mentioned what pre-college and first-year students learned in Brazil, my colleagues and students could not believe me. The [Brazilian] training today is still heavily focused on division, subdivision, and pulse skills. (Januário 2025)4 A. Januário, personal communication, August 22, 2025.

Unlike typical North American post-secondary rhythmic training, Brazilian rhythmic pedagogy teaches RSE.

RSE Differences Among Instruments and Voice

The artists quoted above, apart from the pianist Leon Fleisher, are string and brass musicians; and my own knowledge stems from my career as an oboist and pedagogue. Regarding RSE across instrumental groups, voices, and musical styles, any music student could benefit from enhanced RSE—however classical music students of string, woodwind, and brass instruments are probably the most in need of RSE improvement. One reason for this is that they normally learn music, and even rehearse and perform music, from the printed page. Printed music can draw the musician’s awareness away from the small rhythmic subdivisions. Another reason is that they play melodically, usually one note at a time. Focusing primarily on the melodic line with its varying durations can also draw attention away from the rhythmic subdivisions. Nothing about string and wind playing requires the musician to maintain awareness of the rhythmic subdivisions. Perhaps this is why the quotes I was able to find on the topic of subdivision/RSE are from classical piano, string, and brass pedagogues.

Jazz, popular, and folk musicians generally perform music from memory, which is a huge advantage in terms of RSE as one is unfettered by the printed page that, as just noted, can draw attention away from the smaller rhythmic subdivisions. And most jazz music has rhythmic content as a prominent, central element. Although the quality of RSE varies among jazz, popular, and folk musicians.

Musicians from many traditions around the world use the smallest subdivisions as the main organizing units, as in Middle Eastern, Indonesian, Ghanaian, and Indian Classical music, for example. Musicians in these traditions are likely to use excellent RSE.

Percussionists generally subdivide well due to the nature of their work, although there is a range of RSE skill even among percussionists.

Keyboardists are almost always engaging with rhythmic complexity and different rhythmic values simultaneously using both hands, and the feet as well in the case of organists. They synchronize many rhythmic elements and physical movements as they practice. But like percussionists, pianists’ rhythmic skill in terms of RSE varies widely.

Vocalists of all kinds tend to perform from memory; and they engage with language, diction, voicing, and movement/choreography while they practice, making their RSE different from instrumental RSE and more engaged in its own unique way. However, vocalists need excellent rhythm as much as any musician and would benefit from enhanced RSE.

Any musician can be synchronizing their thoughts and actions very skillfully without consistently synchronizing them all with the smallest rhythmic subdivisions. This is why is it possible to have advanced technical skills but weak RSE.

Across musical genres, instruments, and voice areas, there is a broad spectrum of RSE. While my experience leads me to believe that, of these, classical string, woodwind, and brass music students tend to be the most in need of enhanced RSE, all music students need excellent RSE to practice, learn, and perform optimally and to support their mental health. Every music student could benefit from enhancing their RSE.

Further research could focus on best practices for RSE pedagogy. Brazilian rhythmic pedagogy could serve as inspiration for establishing future best practices in North American schools of music.

Looking at RSE Through the Lenses of Wellbeing Disciplines

Deliberate Practice

While the amount of time a musician commits to practicing their craft is crucial to their development, the quality of their practice is equally, if not more, important. Our understanding of deliberate practice is largely due to the groundbreaking work published in 1993 by the psychologist K. Anders Ericsson, who coined the term “deliberate practice,” and by the many others who have contributed research to the field of elite human performance since then (Ericsson, Krampe, and Tesch-Romer 1993, p. 363).

Deliberate practice is characterized by the musician being alert and focused while working outside of their comfort zone on challenges that are demanding enough that the outcome is uncertain while not so demanding as to be overwhelming. The musician keeps track of how they are progressing. They need frequent, high-quality feedback from an expert mentor who has already mastered what they are trying to learn, as well as in-practice self-assessment, feedback from peers, and reflection from listening to recordings of their practice. Using outside perspectives for gauging progress is crucial since the capacity to assess one’s own progress with accuracy is limited (Ericsson and Harwell 2019).

It is my observation that RSE is one of the best ways to initiate and sustain deliberate practice. As noted above, during practice, a music student must focus on a goal that is just within reach and that requires hard work to achieve. And throughout, they need to be able to gauge how they are doing and to give themselves feedback. When the student sets their goal for practice and begins RSE with the smallest rhythmic units (say 16th notes at a medium tempo), they are creating a kind of temporal grid for themselves. If a metronome is being used as well, it will generally be on a larger rhythmic unit than the subdivisions—a quarter note, for example. The stream of sixteenth notes the student self-entrains with is flexible and alive, conducive to creativity, rubato, timbral changes, dynamic changes, and so on. This kind of practice will tend to encourage the student to set clear, actionable practice goals. All this will likely increase the student’s interest on many levels and make them feel they are “on the right track,” which causes the brain to release dopamine, improving their motivation. Thus, RSE is an excellent tool for a music student to achieve and maintain deliberate practice.

Frustration, anxiety, and excessive stress during music practice are largely curtailed by deliberate practice since the attention it requires leaves little to no mental space for those unhelpful thoughts and feelings. The student is deeply focused on the processes employed during practice, striving to achieve discrete, moment-to-moment goals, and assessing their progress before continuing to their next small goal. The student is like a rock climber free climbing a cliff that is almost beyond their abilities to conquer, but that they can scale with hard work and focused attention. A session of deliberate practice is like climbing that challenging cliff: an absorbing, focused activity that includes both struggle and reward.

Fixed and Growth Mindsets

Carol Dweck’s landmark book, Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, lays out two mindsets, “fixed mindset” and “growth mindset” that further illuminate the benefits of RSE. Countless follow-up articles have made these concepts about mindsets widely known and applicable to many contexts. A fixed mindset is the belief that one’s traits and abilities are fixed and innate, while a growth mindset is the belief that, with effective effort, one can learn anything (Dweck 2007, pp. 15-25):

For individuals with a growth mind-set, who believe intelligence develops through [effective] effort, mistakes are seen as opportunities to learn and improve. For individuals with a fixed mind-set, who believe intelligence is a stable characteristic, mistakes indicate lack of ability […] It is critical to note that these mind-sets are associated with different reactions to failure. Fixed-minded individuals view failure as evidence of their own immutable lack of ability and disengage from tasks when they err; growth-minded individuals view failure as potentially instructive feedback and are more likely to learn from their mistakes. (Moser, et al. 2011, p. 1485)

Using RSE during practice is a key part of the “effective effort” that leads to musical learning and advancement in a growth mindset. I have found that students using embodied RSE tend to feel that they are moving in the right direction and working effectively. Thus, they are often able to respond to imperfections and mistakes (failures) with curiosity, good humour, and helpful problem-solving.

Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation

Intrinsic motivation is an inner drive that impels someone to engage in an activity simply for the pleasure of doing it, the meaning it has for them, or the joy it brings them. They are not engaged for any external reward they might receive in the future. On the other hand, extrinsic motivation derives from external sources in the form of, for example, approval from a teacher or parents, a competition one wants to win, or the potential for financial reward.

Extrinsic motivation is unavoidable in life and can be both positive and negative. For music practice, however, extrinsic motivation is generally problematic as it tends to focus the musician’s attention on pleasing and impressing others rather than simply enjoying the process of music making and learning. Extrinsic motivation is like fixed mindset in that it focuses on outcomes rather than process. Similarly, extrinsic motivation can lead to anxiety, stress, and burnout.

Intrinsic motivation is closely tied to growth mindset in that they both lead one to focus on process and progress rather than outcomes. Both are known to promote learning and persistence. Intrinsic motivation in music practice is the innate curiosity and exploration that drives the student to enjoy learning music and refining their technique, and to derive personal satisfaction and fulfillment from these experiences and accomplishments (Jensen and Mycyk 2023, pp. 16-17). A student engaging in practice for its own sake, for the pleasure of learning and growing, is more likely to have positive outcomes such as lower stress and anxiety, more enjoyment, and lower risk of burnout.

Using RSE while practicing, rehearsing, and performing supports intrinsic motivation the same way it supports growth mindset: by focusing the student’s attention on the internal dimensions of the music rather than only the external. The student tuned in to small rhythmic units cannot ruminate on the judgment and outcomes associated with extrinsic motivation; their attention is focused on the intrinsic qualities of the music and the processes of practice and learning.

Self-Efficacy Theory

Developed by Albert Bandura, self-efficacy is defined as “belief in one’s capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce given attainments” (Jensen and Mycyk 2023, p. 13).

A music student with strong self-efficacy feels they can meet and overcome challenges. They feel involved, engaged, and committed to their practice, and they recover quickly from failures and setbacks. They take responsibility for their failure and think strategically of new approaches that will work better in the future. They view forthcoming scary situations as opportunities to do their best and exercise effective control over themselves (Jensen and Mycyk 2023, p. 13).

RSE creates a grounded, secure feeling in the student’s mind and body because self-entrained rhythmic subdivisions are clear, embodied, and reliable. The nuanced and detailed rhythmic awareness is reassuring and encouraging; it enhances confidence and a sense of self-efficacy. The student is not primarily focused on “trying to be right” or proving their self-worth, which can be intimidating and discouraging. They are staying mentally and physically self-entrained with the smallest rhythmic units, which causes them to experience more agency and self-efficacy.

Flow

The psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi published his book Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience in 1990. While the experience of “flow” has arguably been a part of the human experience forever, it is increasingly discussed in the fields of educational psychology and music pedagogy. According to Csíkszentmihályi, the eight characteristics of the state of flow are:

- Complete concentration on the task

- Clarity of goals and reward in mind, receives immediate feedback

- Transformation of time (speeding up or slowing down)

- The experience is intrinsically rewarding

- The work feels effortless

- There is a balance between challenges and skills

- Actions and awareness are merged, loss of focus on the self

- A feeling of having control over the task (Oppland 2016)

During flow, the brain’s prefrontal cortex—which normally produces thoughts about the self, worrying, and other conscious ruminations—is temporarily less active. This silences the inner critic and allows the person to experience the above eight characteristics. “Moreover, the inhibition of the prefrontal lobe may enable the implicit mind to take over, allowing more brain areas to communicate freely and engage in a creative process” (Oppland 2016). The more a person experiences flow, the happier and more content they tend to feel.

Researchers have examined experiences of flow in students and found that flow is an important predictor of subjective emotional wellbeing (Fritz and Avsec 2007). They have also investigated student engagement in learning and found that highly motivated learners experience higher levels of flow (Mills and Fullagar 2008, p. 535).

Being in a state of flow with less activity in the prefrontal cortex allows the student to relax their focus on themself and become more engaged in creativity, with increased interactions between different parts of the brain. As Ralske specifically mentions above, subdividing is what brings a musician into the zone, focused on only the present tense. This is flow. Music students experiencing flow during practice sessions find it helpful for both their musical learning and their mental health.

Positive Psychology

The field of positive psychology generally takes the approach of identifying aspects of any given situation that are already going well and building on them to make improvements (Seligman and Csíkszentmihályi 2000, p. 13). This works beautifully in human psychology and in many human endeavors, including music practice. Musicians have begun to recognize more deeply that wellbeing skills complement and amplify musical skills. Healthy, content, satisfied, and optimistic music students make progress more easily than frustrated, stressed, and anxious students.

Rhythm is arguably the most tangible and objective aspect of music practice. For almost every style and period of music, rhythmic organization creates the framework for the other structural aspects of music: melody, harmony, and timbre. When a musician establishes and maintains a keen awareness of the smallest rhythmic subdivisions during practice with RSE, they are creating a psychological platform and framework for what is going well, which the musician can use to support everything else.

Positive psychology, like the other wellbeing approaches we have discussed, is effective for decreasing or eliminating frustration, which is probably the most common complaint we hear from music students about practice. Someone who is frustrated is “feeling discouragement, anger, and annoyance because of unresolved problems or unfulfilled goals, desires, or need”(Merriam-Webster.com 2025).

The unpleasant feelings of mindlessness, anxiety, and stress during practice occur when students focus on themselves and the outcomes of their efforts rather than on the processes and quality of their practice. Learning to implement positive psychology in the form of RSE during practice sessions can equip students to minimize the very common but unhelpful human instinct to focus on negatives (negativity bias) and, instead, to choose to focus on what is already going well as they practice, have reasonable expectations of themselves, and enjoy the processes as they practice.

Dopamine and Motivation

We know from the fields of psychology and neuroscience that the brain’s dopamine baseline is key for healthy brain function. Among its other impacts on learning, release of the neurotransmitter dopamine creates motivation and drive, which lead to feelings of reward and pleasure. “Dopamine is […] one of the oldest neurotransmitters, its function being extraordinarily conserved across nearly all animal species, from roundworms to humans […] Currently, dopamine is known to have an essential role in nearly all cognitive functions, including motor control, motivation, and learning” (Costa and Schoenbaum 2022).

An effective way to release dopamine during any kind of intense work, such as running a race, studying for a math exam, or practicing music is to take a moment to reflect and recognize the progress one is making and note—or even better, to say aloud—“I’m moving in the right direction.” This kind of affirmation causes the brain to release dopamine, which increases motivation. Taking the example of a thirsty bear in the wild: they feel thirsty, and their brain’s subsequent changes in levels of dopamine motivate them to seek water. When they find some water and taste it, their brain recognizes that they are moving in the right direction and releases more dopamine to ensure they continue to seek more water.

A practicing music student can benefit from the same process as the thirsty bear. By focusing on the progress they are making while practicing, even the tiniest improvements, and using them as encouragement, noting for example, “This passage is still too slow, but I’m getting there,” the student maintains the kind of brain chemistry that aids motivation and progress, steadily releasing dopamine among other helpful neurotransmitters.

A student who is not using RSE during practice is likely to lack optimal motivation and engagement. For example, “holding a dotted half note” while counting, say, quarter notes, is frankly rather dull. And failing to use RSE inhibits, for example, intonation refinements, timbral development, and style/phrasing.

On the other hand, a student self-entraining with the smallest rhythmic units while holding that same dotted half note is likely to feel engaged, creative, and focused. They will naturally adjust intonation, for example, throughout the note, timbre, dynamics, and so on because of their physical/mental engagement with the flow of the rhythmic pulse. This rhythmic clarity and freedom tend to give the practicing student the implicit and explicit sense that they are “moving in the right direction.” The self-entraining student’s brain, we may assume, is releasing neurotransmitters like dopamine that motivate them to continue their work, and to experience reward and pleasure as they do so.

Zen Philosophy

Zen philosophy has existed for over two thousand years and offers much wisdom and guidance for musicians. Zen advises us to keep the focus off ourselves and our ego, and by extension to allow the process of practicing—and the music itself—to be at the center of attention. Musicians and musical pedagogues have embraced Zen philosophy as helpful guidance since at least 1948 when the Eugen Herrigel book, Zen in the Art of Archery, was published.

Zen encourages one to let go of the desire to accomplish goals, and to focus instead on the present, free from desire and judgment. The Zen tenets, “Think of the small as large” and “Accomplish the great task by a series of small acts,” for example, support the use of RSE. (Tzu and Mitchell 1988, p. 67)

RSE is an excellent path to Zen and mindfulness—living in the moment—since the smallest rhythmic units constantly renew their energetic stream of rhythm, motion, and energy, and are always in the present.

Conclusion

This article has looked at the long-standing tradition of teaching students to subdivide and renamed it “rhythmic self-entrainment” to emphasize its depth and complexity. Through the words of various pedagogues and authors, we have seen that true RSE is embodied, internal, kinesthetic, highly engaging, and a fundamental element of optimal music making.

Turning to wellbeing disciplines to reframe RSE as an effective way to improve mental wellbeing, we have explored how RSE creates, supports, and enhances deliberate practice, growth mindset, intrinsic motivation, self-efficacy, flow, positive psychology, dopamine/motivation, and Zen philosophy.

The use of RSE during music practice is consonant with all these disciplines and could therefore effectively help prevent and reduce the common malaises music students report during practice, including frustration, anxiety, mindlessness, and excessive stress. Students applying RSE to their practice would likely enjoy greatly enhanced wellbeing.

While this article frames RSE as a “panacea” and we have examined evidence supporting RSE’s broad helpfulness, its panacean effects apply only within practice-related areas. Some of the difficulties faced by music students, and indeed professional musicians, lie apart from actual music-making. These can include not being able to afford a better instrument, having a difficult colleague, or experiencing an injury or illness. RSE cannot help directly with such challenges, but its implementation in daily practice can benefit music students in many essential ways, as detailed above. The positive impacts of RSE could only help music students cope with the non-musical challenges of their lives.

The task of guiding music students to a true understanding of RSE and how to employ it reliably in everyday practice falls primarily to the studio teachers and chamber music coaches who see them consistently over long periods of time. How can we as pedagogues better recognize the wealth of mental health benefits RSE offers students and guide them more effectively to use it?

Bibliography

All hyperlinks were verified on January 29, 2025.

Abrams, Zara (2022), “Student Mental Health Is in Crisis. Campuses Are Rethinking their Approach,” Monitor on Psychology, vol. 53, no 7, p. 60. https://www.apa.org, accessed January 29, 2025.

Costa, Kauê Machado, and Geoffrey Schoenbaum (2022), “Dopamine,” Current Biology, vol. 32, no 13, pp. 817-824.

Dweck, Carol S. (2007), Mindset. The New Psychology of Success. How We Can Learn to Fulfill Our Potential, New York, Ballantine Books.

Ericsson, K. Anders, Ralf Th. Krampe, and Clemens Tesch-Romer (1993), “The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance,” Psychological Review, vol. 100, no 3, pp. 363-406.

Ericsson, K. Anders, and Kyle W. Harwell (2019), “Deliberate Practice and Proposed Limits on the Effects of Practice on the Acquisition of Expert Performance. Why the Original Definition Matters and Recommendations for Future Research,” Frontiers of Psychology, vol. 10, https://www.frontiersin.org, accessed January 29 2025.

Ewell, Terry, and Catherine Schmidt-Jones (2013), Music Fundamentals. Unit 2. Rhythm and Meter, https://human.libretexts.org/, accessed January 29, 2025.

Fritz, Barbara, and Andreja Avsec (2007), “The Experience of Flow and Subjective Well-Being of Music Students,” Horizons of Psychology, vol. 16, no 2, pp. 6-17.

“Frustrated,” Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/frustrated, accessed January 29, 2025.

Gebrian, Molly (2024), Learn Faster, Perform Better. A Musician’s Guide to the Neuroscience of Practicing, London, Oxford University Press.

Gramani, José Eduardo (2013), Rítmica, São Paulo, Editora Perspectiva Ltda.

Jensen, Hans Jørgen, and Oleksander Mycyk (2023), PracticeMind for Everyone, Chicago, Ovation Press.

Kageyama, Noa (2018), “Julie Landsman. On Getting into the Zone and Developing Trust in Your Playing”, https://bulletproofmusician.com, accessed January 29 2025.

Kageyama, Noa (2024a), “Erik Ralske. How to Develop a Stronger Internal Pulse and the Paradoxical Benefits of Giving Yourself Permission to Miss Notes,” Bulletproof Musician, https://bulletproofmusician.com/, accessed January 29, 2025.

Kageyama, Noa (2024b), “Steven Tenenbom. On Rhythm, Phrasing, and the Life within Each Note,” Bulletproof Musician https://bulletproofmusician.com/, accessed January 29, 2025.

Kegelaers, Jolan, Michiel Schuijer, and Raôul Oudejans (2021), “Resilience and Mental Health Issues in Classical Musicians. A Preliminary Study,” Psychology of Music, vol. 49, no 5, pp. 1273-1284.

Kurganov, Daniel, (2020a), “Top 10 Tips for Rhythm & Pulse (Part 1)”, YouTube video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SGYsOSVItzY&t=532s, accessed January 29, 2025.

Kurganov, Daniel, (2020b), “Top 10 Tips to Improve Rhythm & Pulse (Part 2)”, YouTube video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F_kGQvnTBb4&t=4s, accessed January 29, 2025.

Mills, Maura J., and C. J. Fullagar (2010), “Motivation and Flow: Toward an Understanding of the Dynamics of the Relation in Architecture Students,” The Journal of Psychology, vol. 142, no 5, pp. 533-556.

Moser, Jason, et al. (2011), “Mind Your Errors,” Psychological Science, vol. 22, no 12, pp. 1484-1489.

Mowreader, Ashley (2024), “Survey. Getting a Grip on the Student Mental Health Crisis,” Inside Highered, https://www.insidehighered.com, accessed January 20, 2025.

Oppland, Mike (2016), “8 Traits of Flow According to Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi,” Positive Psychology, https://positivepsychology.com, accessed January 29, 2025.

Ralske, Erik (2021), “Five Essential Reasons to Subdivide,” Horn Society, https://www.hornsociety.org/, accessed January 29, 2025.

Seligman, Martin, and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (2000), “Positive Psychology. An Introduction,” American Psychologist, vol. 55, no 1, pp. 5–13.

Starer, Robert (1969), Rhythmic Training, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Hal Leonard Corporation.

Teal, Larry (1955), Studies in Time Division. A Practical Approach to Accurate Rhythm Perception, Ann Arbor, University Music Press.

Tzu, Lao (1988), Tao te Ching, translation by Stephen Mitchell, New York, Harper & Row, Publishers.

| RMO_vol.12.2_Leclair |

Attention : le logiciel Aperçu (preview) ne permet pas la lecture des fichiers sonores intégrés dans les fichiers pdf.

Citation

- Référence papier (pdf)

Jacqueline Leclair, « Rhythmic Self-Entrainment. A Panacea », Revue musicale OICRM, vol. 12, no 2, 2025, p. 155-178.

- Référence électronique

Jacqueline Leclair, « Rhythmic Self-Entrainment. A Panacea », Revue musicale OICRM, vol. 12, no 2, 2025, mis en ligne le 11 décembre 2025, https://revuemusicaleoicrm.org/rmo-vol12-n2/rhythmic-self-entrainment/, consulté le…

Autrice

Jacqueline Leclair, McGill University

Jacqueline Leclair is Associate Professor of Oboe at McGill University. She formerly served on the faculties of the Manhattan School of Music, Mannes College, and Bowling Green State University. Leclair worked with Luciano Berio on her 2000 edition of Sequenza VII. She has performed internationally throughout her career and recorded for Nonesuch, CRI, Koch, Deutsche Grammophon, and CBS Masterworks. In addition to her musical research interests, she has for many years supported the wellbeing of music students and launched various initiatives to help them cultivate better mental and physical health during their studies and careers.

Notes

| ↵1 | J. Eissenberg, personal communication, July 26, 2024. |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | See Preface, paragraph 1. |

| ↵3 | “O objetivo deste trabalho é tentar trazer o ritmo musical mais próximo de sua realização total, tentar colocar o ritmo realmente como um elemento MUSICAL e não somente aritmético.” Translated by André Januário. |

| ↵4 | A. Januário, personal communication, August 22, 2025. |