Pressing Rhythms and Korean Percussion Music

Richard Cohn

| PDF | CITATION | AUTHOR |

Abstract

Jeff Pressing identified a group of seven jazz scale-classes that lack [0, 1, 2] subsets, but any added note would create a [0, 1, 2] subset. This article introduces Pressing rhythms in 12-beat cycles, which lack three consecutive onsets, but to which an added onset would create a three-onset run. The seven Pressing rhythm classes are prominent in p’ungmul, a genre of South Korean ensemble drumming that has been extensively researched by Nathan Hesselink. Juxtaposition of Pressing rhythms exploits the close parallelisms between them, with incremental one-onset changes akin to parsimonious voice leading between scales or chords.

Keywords: drumming ensembles; Pressing scales; p’ungmul; rhythmic reduction; South Korea.

Résumé

Jeff Pressing a identifié un groupe de sept classes de gammes de jazz dépourvues de sous-ensembles [0, 1, 2], mais auxquelles toute note ajoutée créerait un sous-ensemble [0, 1, 2]. Cet article présente les structures modales de Pressing appliquées au domaine du rythme, sous la forme de cycles de 12 battements, dans lesquels il y a absence de séquences de trois battements consécutifs, mais auxquels l’ajout d’un battement produirait nécessairement un groupe de trois battements successifs. Les sept classes de rythmes de Pressing occupent une place importante dans le p’ungmul, un genre de musique percussive sud-coréenne qui a fait l’objet de recherches approfondies par Nathan Hesselink. La juxtaposition des rythmes de Pressing montre des parallélismes étroits entre eux, avec des changements incrémentiels lorsqu’on passe de l’un à l’autre, semblables à la conduite parcimonieuse des voix entre des gammes ou des accords.

Mots clés : Corée du Sud ; ensembles percussifs ; gammes Pressing ; p’ungmul ; réduction rythmique.

Introduction

Models of musical pitch are considerably more elaborate than those of musical time. Theorists of musical rhythm frequently adapt concepts from the richer domain of pitch, changing what needs to be changed. Augustine of Hippo observed that two successive verse-feet could “dissonate” with each other;1 See Augustine, On Music, trans Robert Catesby Talliaferro, Washington, Catholic University Press, 2002, p. 238 and p. 276. Porphyry of Tyre noted that time points, like pitches, are perceived categorically, and lose their identity if packed too closely together (Barker 2015, p. 81); and medieval theorists established rhythmic modes in analogy with scalar ones. In the 18th century, Leonhard Euler based a structural model of musical rhythm, and John Holden a cognitive-perceptual one, on analogies with acoustic consonance (Grant 2013, pp. 245–286; Raz 2018, pp. 205–248). And among modern music theorists, Milton Babbitt applied 12-tone serialism to 12-beat cycles; Maury Yeston proposed a theory of rhythm sets modeled on Allen Forte’s theory of pitch-class sets; and Jay Rahn shows that maximal evenness is a useful descriptor of rhythms as well as of scales (Babbitt 1962, pp. 49–79; Yeston 1974; Rahn 1996, pp. 71–89).

It is unclear whether these cross-domain adaptations are based on some physical affinity between pitch and time, on some neurobiological affinity of human processing, or are merely heuristically productive. On the one hand, acoustic pitches are determined by temporal wave frequencies; in that sense, pitch is periodic time, as Karlheinz Stockhausen famously observed (Stockhausen 1957, pp. 39–40). On the other hand, we process pitch and time patterns in very different experiential registers; the sensations stimulated by a beat with a frequency of 4 Hertz seem unrelated to those stimulated by a frequency 100 times faster. This article aims to show that a group of scales that share a particular property have analytically productive analogues in the temporal domain.

* * *

In 1978, the American-Australian ethnomusicologist and research psychologist Jeff Pressing noted that the most prominent jazz scales share two related properties (1978, pp. 25–35).2 For a summary of Pressing’s musical activities, and his unusual path through multiple research disciplines, see Ben Williams (2003), “Encomium for Jeff Pressing,” Music Perception, vol. 20, no 3, pp. 215-221. First, they have no [0, 1, 2] subsets. Playing a scale in ascending order, and encountering a semitone, the next interval is not also a semitone. No element of the scale, accordingly, is hemmed in on both sides by other scalar elements, and so each element can thus “move to” at least one adjacent one without altering the cardinality of the scale. Following Dmitri Tymoczko, I shall refer to this first property as the no consecutive semitones (NCS) constraint (2004, p. 227). Second, any pitch class added to one of Pressing’s selected jazz scales creates an [0, 1, 2] subset, i.e., a pair of consecutive semitones. I will call this the maximal cardinality constraint. Again following Tymoczko, I will refer to scales with both properties as Pressing scales.

For example, both whole-tone scales lack [0, 1, 2] subsets, thus conforming to the NCS constraint, and addition of any absent pitch class (i.e. from the other whole-tone scale) creates an [0, 1, 2] subset, thus adhering to the maximal cardinality constraint. Therefore, whole-tone scales are Pressing scales. By contrast, a gapped whole-tone scale, such as {C, D, E, F#, G#}, is not a Pressing scale, Although it adheres to the NCS constraint, it fails the maximal cardinality constraint. Addition of A, A#, or B creates a six-element superset that lacks a [0, 1, 2] subset.

There are fifty-seven Pressing scales, each with between six and eight elements. Assuming that scales related by transposition represent a single structural class, these fifty-seven scales group into seven classes. The following list identifies each class with a single letter, and represents it by a prototype form, and also by its interval necklace, a series of step intervals. Each necklace is considered to be equivalent to each of its cyclic permutations.

- two whole-tone scales, W, prototype [0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10], interval necklace 2 2 2 2 2 2

- four hexatonic scales, H, prototype [0, 1, 4, 5, 8, 9], interval necklace 1 3 1 3 1 3

- twelve diatonic scales, D, prototype [0, 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 11], interval necklace 2 2 1 2 2 2 1

- twelve acoustic scales, A, prototype [0, 2, 4, 6, 7, 9, 10], interval necklace 2 2 2 1 2 1 2

- twelve harmonic minor scales, m, prototype [0, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 11], interval necklace 2 1 2 2 1 3 1

- twelve harmonic major scales, M, prototype [0, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 11], interval necklace 2 2 1 2 1 3 1

- three octatonic scales, O, prototype [0, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 11], interval necklace 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 1

Some of these scales bear other common names associated with different repertories and pedagogies. Hexatonic (H) and octatonic (O) scales are, respectively, augmented and diminished scales among jazz musicians. The acoustic (A) scale, with the prototype rotated to begin a perfect fifth higher, is the melodic minor scale in classical pedagogy. The harmonic major scale (M), a major scale with a flatted sixth degree, was prominent in some strains of 19th-century pedagogy but is not often mentioned in current English-language textbooks (Riley 2004, pp. 1–26).

Intuitively, some of the scales closely resemble each other. Any of the forty-eight heptatonic Pressing scales can be transformed into at least one transposition of each of the other three scale classes by substituting a single pitch class for its chromatic neighbour. For example, a C major scale can become A harmonic minor by G¡æG#, C harmonic major by A¡æAb, and F acoustic by E¡æEb. The notion of proximity that underlies this intuition is the same one that underlies relations among triads in neo-Riemannian theories of chromatic harmony: in both cases, two cardinality-equivalent sets are most closely related if one of the elements is transformed by the minimal unit motion of a single semitone, while the other elements remain invariant (Cohn 1996, pp. 9–40). The relation is referred to in various ways in the literature; here I shall call it a P1 relation. The only other cardinality-equivalent pair of Pressing scale classes, the whole-tone and the hexatonic, are not P1-related: transforming one to the other requires shifting three non-adjacent elements in a uniform direction.

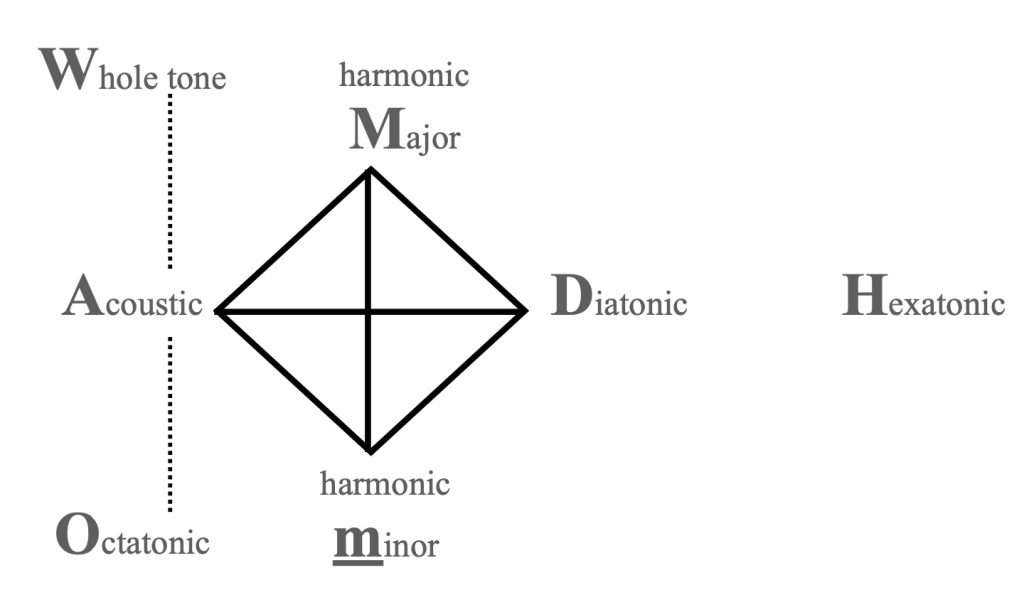

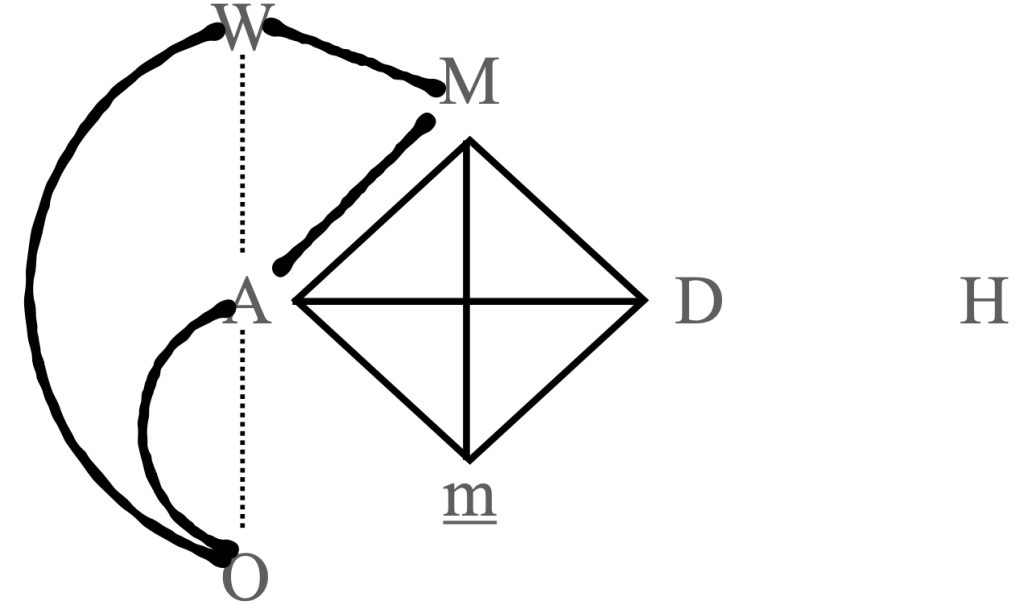

Although scales of different cardinality cannot relate by P1, there are nonetheless some intuitive ways of describing proximity between selected pairs of cardinality-adjacent Pressing scales. A whole-tone scale {0, 2, 4, 6, [8], 10} is transformed to an acoustic scale by replacing any of its individual elements, such as 8 in this representation, by their two scalar neighbours, {0, 2, 4, 6, [7, 9], 10}. Clifton Callender refers to this as a SPLIT/FUSE relation. The acoustic scale {0, [2], 4, 6, 7, 9, 10} is also split/fuse related to one of the octatonic scales, {0, [1, 3], 4, 6, 7, 9, 10} (1998, pp. 219–233). Together, the P1 and SPLIT/FUSE relations imply Figure 1, a graph of voice-leading proximity among the seven Pressing scale classes, in which the acoustic scale is central, and the hexatonic scale is an outlier (Tymoczko 2004, pp. 233–249).3 The graph is adapted from Tymoczko’s, “Scale Networks” but differs in some particulars.

Figure 1: Split/Fuse (perforated edges) and P1 (straight edge) relations among the seven Pressing scale classes.

In 1983, five years after introducing his theory of jazz scales, Pressing published a second article in which he surveyed a broad range of musical structures from many different cultural traditions (1983, pp. 38–61). Pressing observed that many of the most frequently used chords and scales share an abstract structure with many of the most prominent rhythms. For example, the structure of a triad within a diatonic scale, {XoXoXoo} with interval necklace 2 2 3, is replicated in the temporal structure of the rǔcenitsa, a danced music from Bulgaria, where X denotes an overmarked time point in a seven-beat cyclic rhythm. Interpreted as pitch intervals, the 2 2 3 necklace refers to upward distances in diatonic steps, between C and E (2 steps), E and G (2 steps), and G and C (3 steps). Interpreted as temporal intervals, the 2 2 3 necklace refers to time-forward distances in terms of some counting unit, such as an eighth note, indicating a cycled rhythm of (q q q.). Pressing referred to 1:1 pitch/rhythm couplings as “cognitive isomorphisms.”

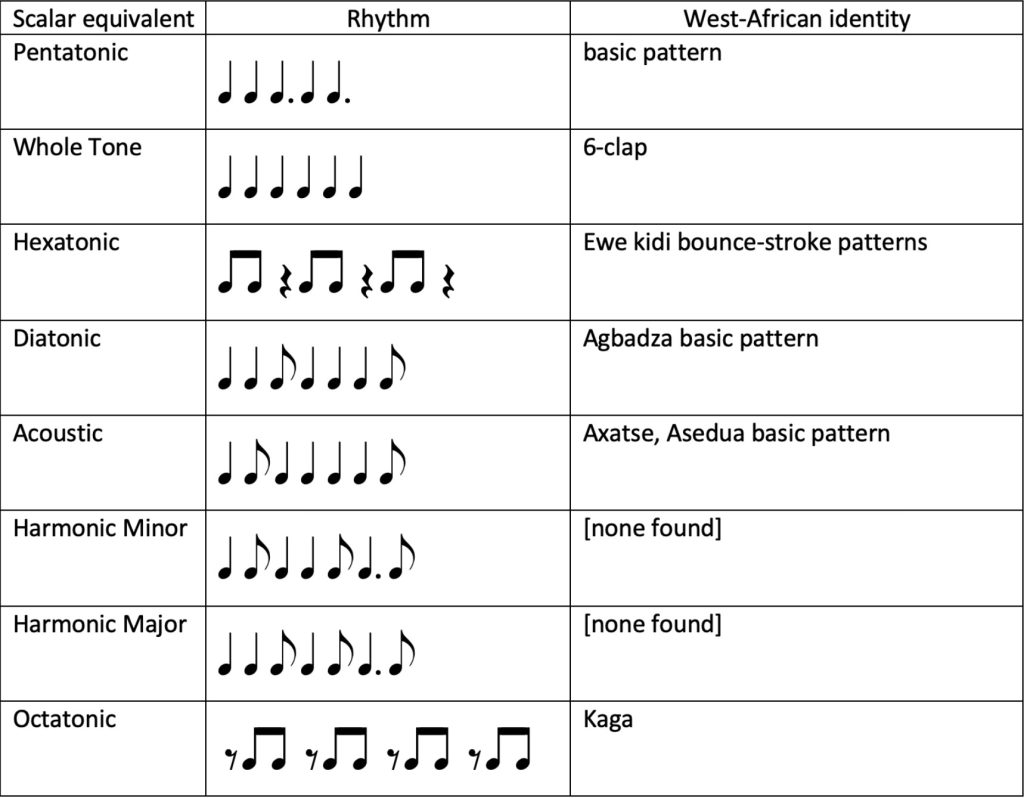

Pressing’s 1983 article makes a passing reference to his own 1978 article: “just the scales used in jazz are particularly well represented in West African rhythm space” (Pressing 1983, p. 46). In a table, adapted here as Figure 2, Pressing presents “the common jazz scale structures and their rhythmic isomorphisms,” and observes that six of these eight rhythms are prominent in at least one West African dance repertory (p. 61).

Figure 2: Adaptation from Jeff Pressing’s Table 5, of West African rhythms (central column) and their identities within those cultures (right column). The left column, not found in Pressing’s article, identifies each rhythm with its isomorphic scale, using the labels favoured in recent writings by music theorists.

Each rhythm has the same number of beats, 12, as there are pitch classes in a chromatic octave, and deposits onsets into between five and eight of the 12 available slots. None of the eight rhythms contains a run of three or more consecutive onsets. That is, onsets are presented either individually, isolated by rests on both sides, or in pairs, isolated on one side but not the other. They thus adhere to the rhythmic equivalent of the consecutive semitone constraint, which I will refer to as the “onset-run constraint.” Moreover, all but the first rhythm is of maximal onset cardinality, in the sense that any added onset would create a run of three. The seven remaining rhythms thus represent the rhythmic equivalents of Pressing’s seven scale classes.

It is not clear how identifying relations among the African bell patterns is analytically productive, since the patterns are inert markers of a dance’s identity. One bell pattern does not replace another mid-dance, and so they engage in no formal processes of interaction or succession. However, 12-beat rhythmic cycles arise with greater-than-chance frequency in many other musical traditions. Among recent analytical literature concerning orally disseminated repertories, twelve beat cycles are observed in vodun rituals of Cuba, Aka polyphony of central Africa, flamenco musics of Spain, funeral lamentations from the Solomon Islands, and celebration music for bamboo ensembles in French Guyana, some of which overlay or move successively between different rhythms, placing them into syntactic interaction (Moore and Sayre 2006, pp. 120–160; Fürniss 2006, pp. 163–204; Jimenez de Cisneros Puig 2017; Roeder 2019).

The remainder of this article examines several audio segments of p’ungmul, a genre of ensemble drumming practiced in rural villages in some regions of South Korea. The same genre is also referred to as nongak, farmer’s band (Howard 1991, p. 1). The analysis builds on Nathan Hesselink’s field recordings, partial transcriptions, analytical observations, and extensive cultural and historical contextualization (2006; 2011, pp. 264–287). Hesselink’s 2011 article presents and analyzes one partial movement, Morigut, and one complete movement, Ch’aegut, which are generically affiliated and often presented together as part of a single performance sequence. The body of each movement alternates a pair, or rotates through a series, of 12-beat rhythms, and then concludes with two stock rhythms, each cycled multiple times: kaenjigen, which prepares the conclusion, and hwimori, which enacts it. Hesselink observes that, in this repertory, juxtaposed rhythms are frequently parallel to each other, with only a single onset displaced one unit earlier or later (2011, p. 248). In the body of Morigut, partially excerpted as Media 1,4 Both audio segments accompanying this article are excerpted from Nathan Hesselink’s 1996 field recordings, and are reproduced here with Professor Hesselink’s generous permission. The same are available at the web site that Oxford University Press hosts in support of the Tenzer/Roeder anthology in which “Rhythm and Folk Drumming” appears. the lead gong alternates the two rhythms in Figure 3.

Media 1: Morigut. Listen to Media 1.

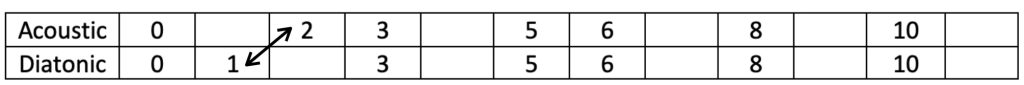

Both are Pressing rhythms: there are no three-onset runs, and no onsets can be added without creating a three-onset run. Every onset is thus free to independently shift one beat earlier, or later, or both, without changing the onset density of the pattern. The first rhythm, {0, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 10} with interval necklace 2 1 2 1 2 2 2, has the same structure as an acoustic scale beginning on its third scale degree. The second rhythm, {0, 1, 3, 5, 6, 8, 10} with interval necklace 1 2 2 1 2 2 2, has the same structure as a Locrian scale, i.e. a major scale initiating from its seventh degree.

Hesselink characterizes p’ungmul as “a collection of work rhythms (but with strong religious overtones) drawn from the age-old custom of communal labor.” In recent decades it has transformed into an entertainment genre, “a historical survivor unmoored to its original context due to the discontinuation of communal labor” (2011, p. 265).5 A more extensive account of nongak’s role in rural Korean culture is presented in Canda (2023). The segments that he analyzes are performed by a core group of four percussionists. These include two gongs: a small one (sangsoe), with high pitch and fast damping that leads the ensemble by sounding out a series of characteristic rhythms, and a larger resonant one (ching), which marks points of cyclic renewal and pattern change. There are also two drums of contrasting shapes, an hourglass (changgo) and a barrel (puk), each attached to their drummer’s torso. The changgo has a low-pitched and loud mallet-struck side and a high-pitched and quieter stick-struck side. In modern performance the musicians are uniformly costumed, and dance throughout the performance while long tassels twirl in their wake. The feet of the dancers characteristically move every three or six beats, both entraining and visually marking beat classes 0, 3, 6, and 9.

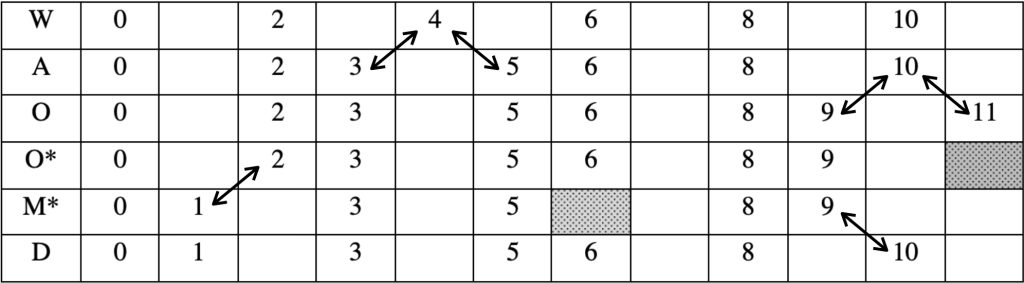

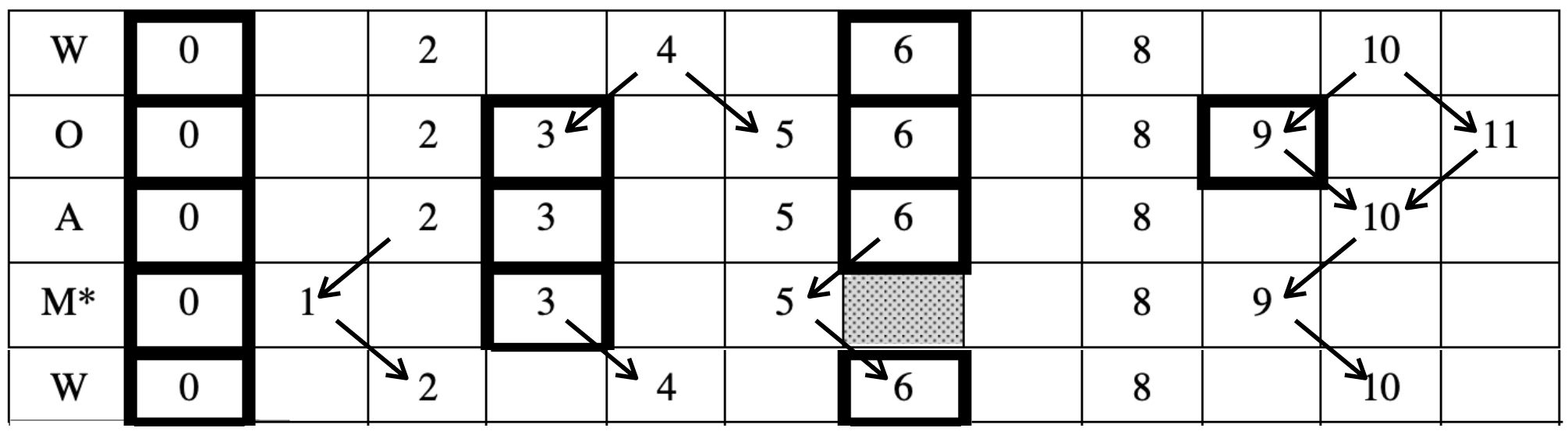

The two rhythms from the body of Morigut are also among six rhythms that are available for use in the body of Ch’aegut, although only four of the six appear in the performance Hesselink presents. In Figure 4, these six cells are relabelled to suit the theoretical perspective of this article, and transcribed in a slightly different format.

Figure 4: The six rhythms that Nathan Hesselink identifies as characteristic of Ch’aegut.

The four with un-starred labels are Pressing rhythms. A and D are the acoustic and diatonic rhythms already seen in Figure 3. W is the only isochronous Pressing rhythm, the equivalent of the whole-tone scale. O is the rhythmic analogue of an octatonic scale, strictly alternating inter-beat spans of different lengths in 2:1 proportion.

The remaining two rhythms, O* and M*, adhere to the onset run constraint but are not of maximum cardinality. O* is a literal subset of O, with only its final onset missing. M* = {0, 1, 3, 5, 8, 9} is isomorphic with a subset of a harmonic major scale, {1, 3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 0}. Both rhythms are dedicated subsets, which become Pressing rhythms through the addition of the onsets flagged in grey. The term “dedicated subset” denotes that this rhythm is a subset of that Pressing rhythm, and no other. It thus can be considered as a representing its unique Pressing-rhythm superset, despite having fewer onsets (Murphy 2024, p. 229).

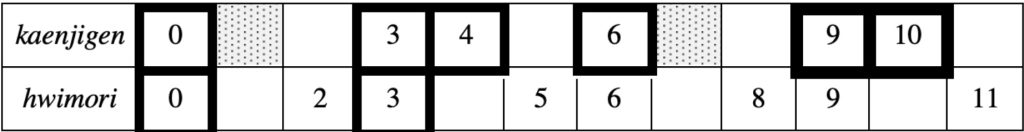

Figure 5: The two stock rhythms cycled at the conclusion of a p’ungmul performance. Kaenjigen is a preparatory rhythm; Hwimori is the rhythm cycled extensively in the final segment of the performance.

The O rhythm, and one of its transformations, has a significant formal function in addition to its participation in rotation with the other five rhythms in Figure 4: one of its unique subsets is the basis for the preparatory kaenjigen, and the complete O rhythm is subjected to extended cycling in the hwimori, the concluding phase of each composition. Figure 5 superimposes these two rhythms, again using grey boxes to indicate the elements that would complete an O collection. The bold frames indicate where the loud mallet of the changgo (barrel drum) strikes. As is evident, the changgo and sangsoe articulate identical rhythms throughout the preparatory passages, but the mallet of the changgo plays only the first two footfall beats of the concluding passage.

In the rhythms of Figure 4, beat classes 0, 3, and 6 are among the most consistently marked by onsets. Class 9 is less frequently marked than the other three footfall beats, but also than the immediately preceding beat 8. It is evident that the footfall beat classes {0, 3, 6, 9} orient the music for both musician/dancers and listeners. Hesselink writes that “the drummer is also dancing with the placement of their feet a strong determinant—perhaps the determinant—of where the beat is felt, especially for listeners who are also watching or participating in the movement” (2022, p. 24).

The lead rhythms differ in the degree to which their onsets coincide with footfalls, ranging from O and O*, where each footfall is marked, to W and M*, whose onsets mostly fall between rather than in synchrony with footfalls. From a Western perspective, these degrees of coincidence suggest metaphors such as consonance and dissonance, stability and tension. One might say, for example, that from the standpoint of the non-watching listener, as well as from the beating hand of the musician, W and M* place pressure on the modes of entrainment projected by the feet, and sometimes suggest alternative modes in their own terms, in which case the musician/dancer is what Steve Friedson refers to as a “human hemiola” (1996, p. 114). Hesselink observes that novices within the culture often shift the periodicity of their footfalls so as to conform to the alternate modes of entrainment projected by their hands and by the acoustic signal (2022, p. 24). Moreover, there exist other p’ungmul pieces where implicit changes in the sonic onset rhythm, for example in W or in the second half of A, generate explicit changes in the dance rhythms, even for experienced musician/dancers (Hesselink 2022, p. 26). Hesselink suggests that these rhythms really do have something akin to the contrametric function that they have in European historical repertories.

Whenever successive onsets are paired in this repertory, one of them coincides with a footfall. If the first of the pair is the coinciding onset, as in the Greek trochee, then the figure is labelled yang. If the second onset coincides with the footfall, as in an iamb, then the figure is ǔm (Howard 2025). The yang/ǔm duality is fundamental to Korean cosmology, the equivalent of yin/yang in China. One of Hesselink’s most esteemed participant/informers associates these rhythms respectively with “resolute strength” and “warm embrace” (2011, p. 280). The distinction is striking in light of the European notion of agogic accent, supported by Povel and Okkerman’s experimental finding that European subjects (albeit only three) spontaneously overmark the second onset of an isolated pair (1981, pp. 565–572). For those subjects, an iambic pair involves less cognitive work than a trochaic one. With reference to p’ungmul, we might speculate that the latter pairing siphons accentual energy away from the footfall points, and thus perhaps requires “resolute strength” in order to stay metrically oriented. However, there are other musical traditions which characteristically overmark the first onset of a pair, not the second (Stobart and Cross 2000, pp. 63–92; Tabak 2022, pp. 45–67). To my knowledge, the Povel and Okkerman experiment has not been replicated cross-culturally, and so we cannot assume that Korean subjects would respond in the same way as Dutch ones.

The repertory itself, however, seems to prefer end accentuation, in terms of both statistical frequency and formal position. Among the cells in Figure 4, eleven of the thirteen adjacent onset pairs end with a footfall point. Moreover, the progression from the trochaic kaenjigen rhythm to the iambic hwimori, documented in connection with Figure 5, suggests that the end-accented pairing is functionally more final, hence perhaps more stable. Hesselink writes that the extensive repetition of the latter rhythm marks the height of communal participation, as the musicians stop whirling through the space and assemble into a circle (2011, p. 275).

The performance of Ch’aegut that Hesselink recorded is reproduced here as Media 2. The movement begins with the lead gong rotating ten times through a series of four 12-beat rhythms in the order presented in Figure 6. The changgo strikes at the points where a sangsoe onset coincides with a footfall, but with a single exception, the final onset of each four-rhythm cycle.

Figure 6: The four rhythms presented in fixed order throughout the first part of Ch’aegut. The first rhythm is reproduced at the bottom for cyclic completion.

Media 2: Chae’gut. Listen to Media 2.

The first transition, from W to O, enacts a double split, of beat classes 4 and 10. The second transition, from O to A, undoes the second split, fusing 9 and 11 back to 10. The third transition, from A to M*, preserves three of the beat classes, but shifts the embedded 4-beat cycle, {2, 6, 10}, one beat earlier, at {1, 5, 9}. The least parsimonious move connects the final 12-beat rhythm back to the initial one: the four odd beat classes are shifted one beat later. The paths of the arrows can be conceived as a kind of voice leading, but applied to onsets rather than to sounding pitches.6 Voice leading, usually applied to chords, is applied to scales in Tymoczko (2008, pp. 1-49). More abstractly, the way that the body of Ch’aegut navigates the space of Pressing rhythms is modelled at Figure 7. The figure makes evident the central position of A, the rhythmic analogue of the acoustic collection, and the relative distance covered by the first and final transition vis-a-vis the two interior ones.

Figure 7: The path of the rhythms of the first part of Ch’aegut through the Pressing rhythms as graphed in Figure 1.

The cycling of four rhythmic cells is abandoned at time stamp 1:12, where the sangsoe focuses exclusively on the final cycle, M* = {0, 1, 3, 5, 8, 9}, cycling it multiple times. The changgo requires several cycles to adjust to this shift, so that the new cycle doesn’t fully groove in until around 1:16. At that point, and for that cycle only, the sangsoe sounds the heretofore missing sixth beat, the only one that would not violate the onset run constraint, and thereby transiently produces the complete M rhythm. The return of the M* form, with its {5, 8, 9} concluding rhythm, links elegantly at 1:37 to the subsequent kaenjigen, which combines two instances of the same rhythm, {0, 3, 4} and {6, 9, 10}, but launching from footfall points, rather than targeting them.

The cycling of M* from 1:12 to 1:37 focuses sustained attention on its most salient feature: the progression from a trochaic pairing at its beginning, {0, 1} to an iambic one at its end, {8, 9}. This progression compresses the structural progression that ends the movement, from the preparatory trochaic kaenjigen to the final iambic hwimori. Perhaps complicating this analysis is the loudly articulated mallet rhythm of the changgo drum, whose {0, 3} rhythm is a trochaic pairing, at one-third the speed. This rhythm threatens to siphon energy away from the point of cyclic renewal, beat class 0, and direct it toward beat class 3. The same changgo mallet rhythm is very evident throughout the hwimori, suggesting a trochaic footfall-launched energy that counter-balances the iambic footfall-targeted energy of the “octatonic” sangsoe.

This article introduces a tool, and applies it to a single repertory as a kind of “proof-of-concept.” Whether it suggests anything meaningful about p’ungmul, or some larger repertory in which it is embedded, is for Koreanist scholars to determine. The question of its applicability to other 12-cyclic music, of which there seems to be a vast variety in many corners of the globe, can only be determined by further applications of the tool, one by one, as seems to be warranted for those who live inside those repertories.

Bibliography

Augustine of Hippo (2002), On Music, translated by Robert Catesby Talliaferro, Washington, Catholic University Press.

Babbitt, Milton (1962), “Twelve-tone Rhythmic Structure and the Electronic Medium,” Perspectives of New Music, vol. 1, no 1, pp. 49–79.

Barker, Andrew (2015), Porphyry’s Commentary on Ptolemy’s Harmonics, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Callender, Clifton (1998), “Voice-Leading Parsimony in the Music of Alexander Scriabin,” Journal of Music Theory, vol. 42, no 2, pp. 219–233.

Canda, Edward R. (2023), Gripped by the Drum. The Inspiring Artistry of Master Percussionist Kim Byong Seop, Lawrence, University of Kansas Libraries.

Cohn, Richard (1996), “Maximally Smooth Cycles, Hexatonic Systems, and the Analysis of Late-Romantic Triadic Progressions,” Music Analysis, vol. 15, no 2, pp. 9–40.

Friedson, Steven M. (1996), Dancing Prophets. Musical Experience in Tumbuka Healing, Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Fürniss, Suzanne (2006), “Aka Polyphony. Music, Theory, Back and Forth,” in Michael Tenzer (ed.), Analytical Studies in World Music, New York, Oxford University Press.

Grant, Roger Matthew (2013), “Leonhard Euler’s Unfinished Theory of Rhythm,” Journal of Music Theory, vol. 57, no 2, pp. 245–286.

Hesselink, Nathan (2006), P’ungmul. South Korean Drumming and Dance, Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Hesselink, Nathan (2011), “Rhythm and Folk Drumming (P’ungmul) as the Musical Embodiment of Communal Consciousness in South Korean Village Society,” in Michael Tenzer and John Roeder (eds), Analytical and Cross-Cultural Studies in World Music, New York, Oxford University Press, pp. 264–287.

Hesselink, Nathan (2022), “Cross-Cultural Resonance in the Cadential Hemiola,” Analytical Approaches to World Music, vol. 10, no 1, https://journal.iftawm.org/previous/2022-volume-10-number-1/10-1-hesselink-2/, accessed January 30, 2025.

Howard, Keith (1991). “Why do it That Way? Rhythmic Models and Motifs in Korean Percussion Bands,” Asian Music, vol. 23, no 1, p. 1–59.

Howard, Keith (2025). “Revisiting Korean Kaein changgu nori. Rhythm Writ Large,” Analytical Approaches to World Music, vol. 13, no 1, https://journal.iftawm.org/previous/2025-volume-13-no-1/howard_2025/#_ftnref5, accessed September 10, 2025.

Jimenez de Cisneros Puig, Bernat (2017), “Discovering Flamenco Metric Matrices through a Pulse-Level Analysis,” Analytical Approaches to World Music, vol. 6, no 1, https://journal.iftawm.org/previous/vol6no1/puig/, accessed January 30, 2025.

Moore, Robin and Elizabeth Sayre (2006), “An Afro-Cuban Batá Piece for Obtalá, King of the White Cloth,” in Michael Tenzer (ed.), Analytical Studies in World Music, New York, Oxford University Press, pp. 120–60.

Murphy, Scott (2024), “An Approach to Scales in Some Twenty-First Century Television Music,” in Janet Halyard and Nicholas Reyland (eds), The Palgrave Handbook of Music and Sound in Peak TV, London, Palgrave MacMillan, pp. 221–243.

Povel, Dirk-Jan and Hans Okkerman (1981), “Accents in Equitone Sequences,” Perception and Psychophysics, vol. 30, no 6, pp. 565–572.

Pressing, Jeff (1978), “Towards an Understanding of Scales in Jazz,” Jazzforschung/Jazz Research, vol. 9, pp. 25–35.

Pressing, Jeff (1983), “Cognitive Isomorphisms in Pitch and Rhythm in World Music. West Africa, the Balkans, and Western Tonality,” Studies in Music, vol. 17, pp. 38–61.

Rahn, Jay (1996), “Turning the Analysis Around. Africa-Derived Rhythms and Europe-Derived Music Theory,” Black Music Research Journal, vol. 16, no 1, pp. 71–89.

Raz, Carmel (2018), “An Eighteenth-Century Theory of Musical Cognition? John Holden’s Essay towards a Rational System of Music (1770),” Journal of Music Theory, vol. 62, no 2, pp. 205–248.

Riley, Matthew (2004), “The Harmonic Major Mode in Nineteenth-Century Theory and Practice,” Music Analysis, vol. 23, no 1, pp. 1–26.

Roeder, John (2019), “Timely Negotiations. Formative Interactions in Cyclic Duets,” Analytical Approaches to World Music, vol. 7, no. 1, https://journal.iftawm.org/previous/vol7no1/roeder2/, accessed January 30, 2025.

Stobart, Henry and Ian Cross (2000), “The Andean Anacrusis? Rhythmic Structure and Perception in Easter Songs of Northern Potosí, Bolivia,” British Journal of Ethnomusicology, vol. 9, no 2, pp. 63–92.

Stockhausen, Karlheinz (1957), “…wie die Zeit vergeht….”, Die Reihe, vol. 3, pp. 39–40.

Tabak, Lina (2022), “Short Notes on Strong Beats. Case Studies in African and Afro-Diasporic Meter,” Musica Theorica, vol. 7, no 1, pp. 45–67.

Tymoczko, Dmitri (2004), “Scale Networks and Debussy,” Journal of Music Theory, vol. 48, no 2, pp. 219–294.

Tymoczko, Dmitri (2008). “Scale Theory, Serial Theory and Voice Leading,” Music Analysis, vol. 27, no 2, pp. 1–49.

Williams, Ben (2003), “Encomium for Jeff Pressing,” Music Perception, vol. 20, no 3, pp. 215–221.

Yeston. Maury (1976), The Stratification of Musical Rhythm, New Haven, Yale University Press.

| RMO_vol.12.2_Cohn |

Attention : le logiciel Aperçu (preview) ne permet pas la lecture des fichiers sonores intégrés dans les fichiers pdf.

Citation

- Référence papier (pdf)

Richard Cohn, « Pressing Rhythms and Korean Percussion Music », Revue musicale OICRM, vol. 12, no 2, 2025, p. 201-212.

- Référence électronique

Richard Cohn, « Pressing Rhythms and Korean Percussion Music », Revue musicale OICRM, vol. 12, no 2, 2025, mis en ligne le 11 décembre 2025, https://revuemusicaleoicrm.org/rmo-vol12-n2/pressing-rhythms-korean-music/, consulté le…

Auteur

Richard Cohn, Yale University

Richard Cohn will be retiring in 2026 as Battell Professor of Music Theory at Yale University, and has been appointed European Union Research Area Chair at the University of Coimbra (2025-2030). He is currently a Visiting Professor at the University of Sydney. He is author of Audacious Euphony: Chromatic Harmony and the Triad’s Second Nature (Oxford University Press, 2012) and of A Simple Mathematics of Musical Pitch and Time (forthcoming). He was founding editor of Oxford Studies in Music Theory, and has served as editor of Journal of Music Theory since 2021.

Notes

| ↵1 | See Augustine, On Music, trans Robert Catesby Talliaferro, Washington, Catholic University Press, 2002, p. 238 and p. 276. |

|---|---|

| ↵2 | For a summary of Pressing’s musical activities, and his unusual path through multiple research disciplines, see Ben Williams (2003), “Encomium for Jeff Pressing,” Music Perception, vol. 20, no 3, pp. 215-221. |

| ↵3 | The graph is adapted from Tymoczko’s, “Scale Networks” but differs in some particulars. |

| ↵4 | Both audio segments accompanying this article are excerpted from Nathan Hesselink’s 1996 field recordings, and are reproduced here with Professor Hesselink’s generous permission. The same are available at the web site that Oxford University Press hosts in support of the Tenzer/Roeder anthology in which “Rhythm and Folk Drumming” appears. |

| ↵5 | A more extensive account of nongak’s role in rural Korean culture is presented in Canda (2023). |

| ↵6 | Voice leading, usually applied to chords, is applied to scales in Tymoczko (2008, pp. 1-49). |